"We really like to base our animation on music. Usually what we do is, first Merav edits the drawn animatic over the sound track, creating a general tempo for the whole piece. Then, while doing the 3D animatic, we fit the more subtle movements and gestures to the bits."

Let the Music Lead

When I first started studying film, I had a wonderful teacher by the name of Martin Reynolds. His love and passion for filmmaking was immeasurable and his high regard for music and sound left an impression on me. He would say;

I never gave this much thought until Martin brought this to my attention. As I started to analyze the films that I followed, I realized that this statement rang true. I am a very visual person, like many filmmakers, and since I am creating visuals for my film, the sound would often fall into the shadow of the pictures. One day I decided to give a live musical performance for one of the film exercises I was screening for Martin’s class. I brought in and played a guiro, which is a hollow, ribbed cylinder of wood played by rubbing a stick across the ribs. This sound, along with the rigging of the sailing ships that I filmed, made an unusual combination that somehow worked and garnered high praise from Martin. From that point on, I promised that my sound tracks would play prominent roles in all of my films, and I have never regretted that commitment.

Ever since the early days of animation, music has played a key role. Some animators follow music and sound effects to the frame, and others have let the sound track become more interpretive and less connected directly to the images.

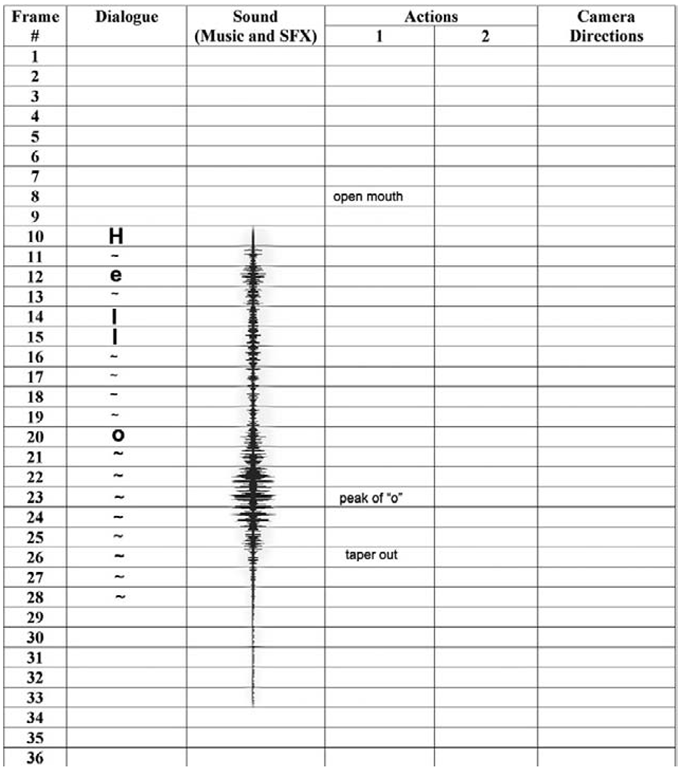

FIG 9.1 Log sheet with sound wave and frame count.

Both approaches have strengths and different effects on the audience. When the music is synchronized directly to the picture, the music drives the picture. If the sound track is interpretative, then the visuals tend to lead the meaning and effect of the film. This is also reflected in the way these two approaches are produced. With synchronized music, the music is created first and broken down in length to the frame. The animator takes those sounds and accounts for them on a log sheet or "dope sheet" so every single frame has an associated sound. This is also the way lip-sync dialog is created. The pictures or mouth shapes follow what the sound dictates. In an interpretive approach, a composer or sound designer is given the moving image, even if it is not completely finished, and starts to create a track based on the general movement and mood of the pictures. Sound effects are usually created this way but require very specific placement on the timeline, so they are synced up to a specific image. Occasionally, original sound effects can be created first and the picture actions follow the broken down analysis of that sound on a log sheet.

William Kentridge, the South African artist and animator, describes his approach to sound tracks:

"Work with the composer starts after about the first two weeks of filming. We look at the rushes, listen to different kinds of music played alongside the images. From here, the film and music go back and forth between the composer’s studio and mine, in an ever-tightening observation."

The great majority of films are produced in this fashion; and a lot of interpretation, spontaneity, and creative flow comes with this production protocol. It is important to work with a composer or sound designer who has experience with moving image sound tracks and understands the rhythm and flow of a narrative or experimental production. Working with a pre-existing sound track and following that track to the frame is a lot more work but the results can be very potent. Here is an exercise to give you a taste of this exacting marriage of sound and picture.

This exercise starts with a music track. I recommend creating an original music track from a program like GarageBand. You certainly can use a composer or make a music track in any other fashion that is easy and effective. The key to this music track is that it needs to be simple, short (10 to 30 seconds long), rhythmic, and feature only one or two instruments (preferably no lyrics). Get that music track into digital form, like an AIFF file or a WAV file. Investing in a program like Quicktime Pro can make a big difference in creating picture and sound tracks. It is also important to note that you need to record the sound track at a rate that you will use for animating, so the picture and sound do not lose synchronization. If you are shooting at 30 frames per second (fps), then you must record at that rate.

If you chose to stick to a film rate of 24 fps, then record at 24 fps. Import that sound track into a program, like Dragon or even Final Cut, that allows you to import sound tracks, shows a waveform for the sound, and has the ability to count every frame and its associated sound in the whole timeline. Our website lists several programs that are good for sound breakdown.

Create a log sheet (illustrated in Figure 9.1). Start stepping through the music track with the forward arrow key frame by frame and locate each sound and the beat or rhythm of your composition. I find wearing headphones really enhances this activity. Write down the sounds and their placement by their associated frame number on the log sheet. The waveform helps you see the dynamics in the music and the regular patterns like the beat. Some sound reading programs, like Magpie Pro, print out a waveform right on their existing log sheet format. This is convenient but not necessary. Once you have your whole music track broken down into frames and recorded on your log sheet, you are ready to animate.

You can use any of the alternative stop-motion techniques, but one of the easiest approaches is to work on a flat surface with objects. Similar to other exercises, you need a digital video or still camera, a tripod, a few small lights, and a solid, stable tabletop. If you use a program like Dragon, then you need to import or load your sound file into the audio timeline. The nice thing about using Dragon is that you have your sound file on the desktop with a total frame count and waveform. The sound automatically syncs up with your picture frame, and you can proceed to animate to your sound track.

Try to choose objects that are related thematically or visually to the style of the music you are using. For example, if your music has a Japanese flavor, then you might consider animating chop sticks and ningyo dolls; if your music leans toward hip-hop, then you might animate sneakers and baseball caps; if your music is light and floating, you might animate feathers and paper. I think you get the idea. Keep in mind the things that you are interested in animating and let them influence your choice of music when you create the track. The objects can be pulled in and out of frame based on the beat and sound of the music. You can move and place your objects around the frame in a way similar to the look of the waveform, with lots of activity when the waveform is large and less movement when the form is small. I find it is helpful to assign a particular object to a particular sound or instrument for clarity. Have fun with this exercise. It takes more time to animate this way because of the constant reference to the sound track. I am sure you will be pleased with the results.

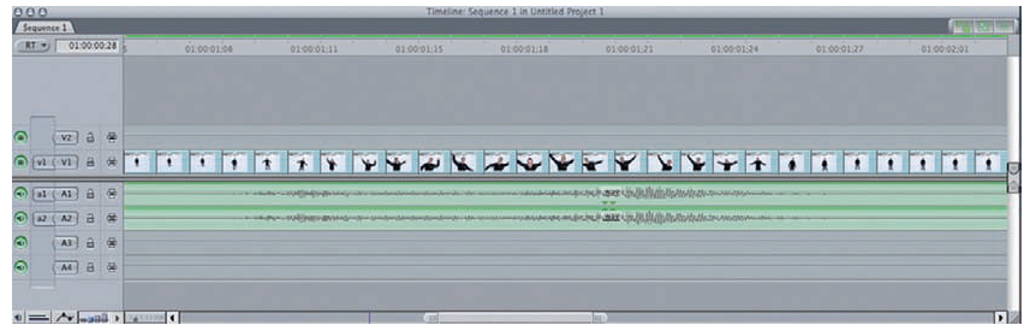

FIG 9.2 A waveform from sound in Dragon Stop Motion.

Patterns of Movement

One can consider frames of animation like musical notes on a scale. This is especially true when visuals are closely linked to sound tracks. Generally, when a waveform rises in size on the audio track, the corresponding visual frame is active or more detailed, reflecting more energy and dynamic. If the sound recedes, then the corresponding image may remain static with little dynamic change. One master of this approach to visual music was Norman McLaren and his many film experiments, including his 1959 Short and Suite and the 1971 Synchromy. McLaren used many different techniques, including drawing directly on 35 mm film with pen and ink. He also used optical printing techniques in Synchromy to create a direct visual link to the sound track.

Fig 9.3 an active sound track and the corresponding visual timeline.

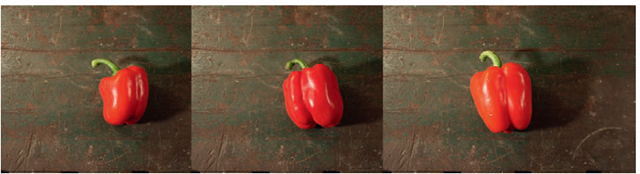

Similar to music, when an animated sequence is highly active, it can be exhilarating to watch. Too much exhilaration can be exhausting, and the audience can start to drift away. It is critical to let your frame and characters rest for even just a moment, so the audience can catch up and digest what is happening and maybe even get a sense of character and thinking from an animated subject. This is practical and adds dynamic to any composition. Even with the lack of sound tracks, object movement and visual frames can have patterns that create certain effects and illusions to the eye. These patterns become recognizable to us because we know their movement even though the objects are not necessarily related to that movement in real life. We saw this in the work of PES. His candy-corn flames and his pepper heart are great examples of movement that have a distinctive pattern. The Pepper Heart features three or four red peppers in increasing size that are replaced one after the other. The first and smallest pepper is held for about eight frames, then each pepper is replaced with a larger pepper. There is a brief hold (four to six frames) on the largest pepper, then the peppers are replaced with smaller peppers (the same three or four peppers), and the smallest pepper is held for eight frames and so forth. PES uses the loop or a cycle of movement mimicking the repetitive beat of a human heart. This creates a visual music of sorts that can be appealing to the eye. The hold along with the changing pepper movement make this a successful sketch.

FIG 9.4 a series of peppers that simulate a heart, pES.

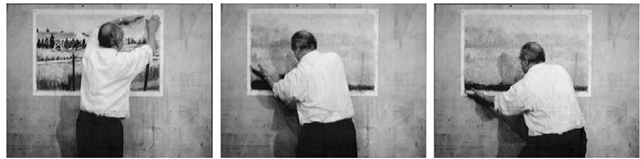

William Kentridge follows his own intuitive approach to movement and patterns. In his Fragments for Georges Melies, which is part of an exhibit that traveled around the world in major venues, Kentridge gives his artwork a life of its own through the use of stop-motion, drawing, and reverse playback techniques. The artwork of one of his drawings appears to sink to the bottom of the frame, until Kentridge enters the frame, frame by frame, and rescues the slumping image. When I asked Mr. Kentridge about his approach, here is how he responded:

"The morning I decide to make a film, I begin. I may have to pause to find an object or image. Thinking about the film starts while setting up the camera … I can make a film without having to sell the idea to a producer. I can practice my craft without being dependent on the whims of anyone else—there is no crew, no cast. I like to use a camera like a typewriter.

"In the long term, my approach is based on a year at the Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris, where there is an emphasis on the expressiveness of gesture throughout the body. In the short term, I find the trajectory of a movement either by watching myself in the mirror, or filming myself or other people with a video camera; or by making a movement in the air with my hand, while counting.

"Objects and images in the films float between being seen as photographic objects, or the things themselves, and provoking other meanings and associations—for example, a cloth draped around a corkscrew is also a woman lifting her arm"

His animated movement is lyrical and so is the pattern and pace of his animation. It unfolds in a mysterious yet simple pattern that makes us wonder about the life of the created image.

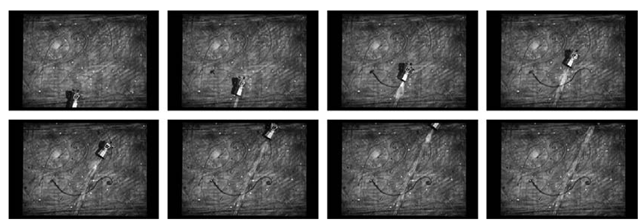

fig 9.5 William Kentridge rescuing the image in his artwork from 7 Fragments for Georges Melies ("Moveable Assets"), 2003 (video stills from installation).

This rhythm and flow of images can be an abstract concept to grasp, but it is often the element that defines a particular piece of animation. It is the artistry. Whether the visuals are tightly matched to a music track or much more interpretive in nature, there does need to be a driving force to carry the film along. Once again we turn to the clay painter, Joan Gratz:

FIG 9.6 A series of images from "Voyage to the Moon," from 7 Fragments for Georges Melies.

"I am interested in creating a ‘visual onomatopoeia’ in which line, color, movement, and rhythm create the feeling of a particular experience without illustrating it."

The Beat Goes On

Often these alternative stop-motion techniques can be employed in the marketplace in the world of the music video. Part of the reason that this formula works is because these photographic stop-motion techniques can be produced on lower budgets and in shorter time periods. Ultimately, it requires a great idea, a good piece of music, and sweat equity. These techniques, especially pixilation, can require a lot of hard physical work, as we discovered. More important, this technique allows audiences to see artists in the magical world of animation with a certain rhythm of movement that cannot be recreated in live action. The Peter Gabriel music video Sledgehammer was an early example of this approach. There are many more examples of this music and picture relationship that have been produced in the last twenty years.

The one area that makes pixilation more time consuming is if the filmmaker decides that the human subject has to lip-sync or mouth the words of the song. This requires more detailed preparation and production and it can be difficult to get exacting results. The subtleties and in-between movement of the human mouth are something we recognize instantly, since we watch each other speak every day. When it is not done exactly the same way, especially with the photographic image of a human subject, then it does not sit quite right. This stylization of animated speaking can be humorous but difficult to pull off, because the mouth shapes are not exacting and it is difficult to get human subjects to emote believable expressions that would normally be associated with words.

Always remember to start your work on any sound track from the very beginning of your animated film preproduction. It is totally up to the filmmaker on how to use a sound or music track, interpretative or literally, but it is always important to infuse that sound track with great importance, so that it carries half of the weight of the film. The image itself has its own rhythm and flow on a timeline, and once sound is introduced, there should be a kind of synchronous dance between the two.