Technique to Serve the Idea

"A lot of people are trigger-happy—they just want to be shooting/ animating all the time, because it makes them feel like they are being productive. But in reality, you are just wasting creative energy if you haven’t done the hard work on your ideas. And it is hard work. There are days when you smash your head against a wall trying to work something out. I spend a lot more time refining my ideas than I actually spend shooting.

"To me, understanding that your ideas are what make you unique is the most important thing. There are many people who can shoot or animate well. That’s not the rare thing. A good idea is the rare thing."

I am always torn between the excitement of jumping directly into the production of an animated idea and approaching an idea with a better thought-out plan. Getting your hands on a camera, simple capture software, and shooting a scene spontaneously can be fresh and exhilarating, until you run into your first challenge or problem. This is especially true when shooting frame-by-frame pixilation of human subjects. Any animation is hard work, and you do not want to waste anyone’s time and energy. Creative ideas need to be drafted and carefully honed to impress any audience these days. We are a visual storytelling society, and much more discerning about filmmaking language than any time before. Having a good idea and an interesting way of telling it gains and holds an audience’s attention, and that is good communication. This planning phase, known as preproduction, is your road map or core idea that gives you direction. It also changes, and that is not a bad thing. There is room for the spontaneous approach, mentioned earlier, in this process, and we come across the subject again later on.

The first step in any film is the idea. What do you want to say? What idea, story, or visual art do you want an audience to receive? Who is your audience? Do you even care that an audience sees your work? There are many filmmakers who have no care for what an audience thinks. These "artists" want only to explore their own vision as best they can to their own satisfaction. This approach requires more risk if you are approach filmmaking as a means of income. But, some of the most successful ideas come from this original thought process. The great majority of filmmakers do care what an audience thinks and tailor their approach to filmmaking to make a connection with the audience. They yearn for a laugh, a gasp, or a tear in reaction to their film. Getting your ideas down on paper can be challenging. Scriptwriting is not an innate talent that most filmmakers possess. It takes practice, guidance, and crafting. There are many topics on this subject so we do not go into this area. Ideas are another matter. I find that the old saying "life is stranger than fiction" rings true. When you draw from your own experiences and the experiences of others you know, you may have a kernel of an idea that can germinate. The effective outcome of this approach is that, if you had an experience and reacted to it in some emotional way, then audiences have a greater access to empathy and your idea, because we all share the human experience. Empathy, not sympathy, is a key ingredient to including an audience. We need to understand a character’s emotion, based on our own experiences, but we do not necessarily have to agree with that emotion.

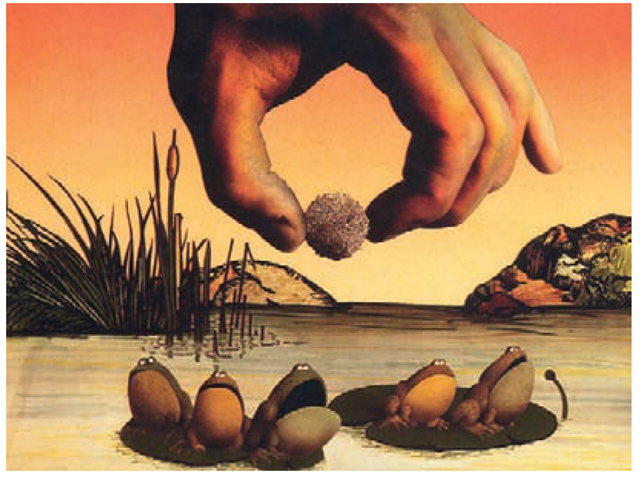

The next step is to take advantage of the process and strengths of animation. Hyperbole or exaggeration and strong images can be used effectively in animation. When real human subjects are not being used as the subject matter, we can address sensitive issues (like sex, death, and the human condition) with human proxies, like animals, aliens, or even everyday objects. You can elicit human emotions and experiences through inanimate objects and get an audience to understand your point. The audience can understand the empathized point and not necessarily feel directly or personally targeted by the subject matter. This is true even in pixilation, the animation of humans, since the movement is unreal or unnatural.

FIG 2.1 Image from Meat!, Lindsay Berkebile, 2010.

FIG 2.2 A production still from The Human Skateboard for Sneaux Shoes, directed by pES.

Fig 2.3 image (pig head)

There are many ways to approach ideas, and the subject is a topic unto itself. The important thing to remember is what you want to say, who your audience is, and how your idea can be clearly expressed through animation.

The great Czech master Jan Svankmajer approaches ideas and process in a less formal way.

"I try to work spontaneously, I let the creative process open to chance and automatism."

Once you have an idea, you need to think about an animated technique that serves the idea or enhances it. For example, a lawyer who is going to demonstrate to a courtroom the events of an alcohol-induced fatal car accident to prove his client’s innocence would be best using an emotionless, naturalistic, demonstration with computer-generated images. Imagine what the results would be if the lawyer showed this demonstration in clay animation or even pixilation. The courtroom might burst into laughter and not take the demonstration seriously. That lawyer would lose the case.

What would Gumby or Wallace and Gromit look like in drawn animation? Many of the old cartoons from the 1950s and 1960s are being updated into computer effects and images, and they just do not sit right. Some of this incongruity has to do with the way a film or character was first conceived. Originally, the choice of some techniques may have had to do more with economics than technique to support the idea. Once a technique is established and an audience embraces that film or character, an animator is treading on thin ice to move a beloved idea or character to a new animation approach. Ultimately, it is important to think about films that have been done in certain techniques and why those techniques were used. If you choose to use pixilation, time-lapse photography, or downshooting techniques, then how does that approach affect your final idea and outcome? Terry Gilliam from Monty Python’s Flying Circus claims:

"I think the limitations of cutouts leads towards comedy or violence. Movements are crude, ungainly, and inelegant. It’s hard to be portentous or pretentious with this technique. However, serious ideas can often be communicated very powerfully with humour"

FIG 2.4 Image from Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Terry

Today, cutout animation is composed with After Effects, Toon Boom, or Flash to smooth out the "violent" approach that Gilliam cites. As a result, more and more kids’ shows are being produced this way. The movement is much more fluid and subtle.

Pixilation has a tendency to also be crude, ungainly, and inelegant by the nature of the process. It is practically impossible to keep a human subject completely still or registered in the same position one frame to the next. The result is a highly active frame that has a bit of a humorous and kinetic appeal. A pixilated Shakespeare would not be a great match (unless humor or parody is what you are seeking).

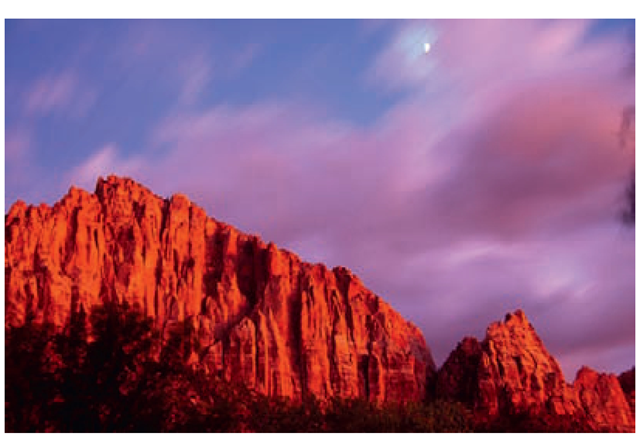

Time-lapse photography, which requires a consistent exposure of frames over a period of time, has a completely different effect. Events are sped up dramatically so time feels compressed into a short span. When a time-lapse camera is pointed at the sky during an oncoming thunderstorm the results can truly be awesome. Clouds look like waves of ocean water and one can see the power of nature.

FIG 2.5 Zion Mountains with clouds, shot by Eric Hanson.

When the time-lapse camera is focused on human subjects or animals, the effect can be a bit more humorous. The fast and unnatural movements remind us of early films, when cameras were undercranked and you would see comedic action, like the incompetent Keystone Kops from Mack Sennett in the early twentieth century.

Fig 2.6 An old hand-cranked camera (Museum of the Moving Image).

Cameras used to be hand cranked or driven, so the number of frames that were exposed per second in the camera was fewer than the number of frames projected per second on a screen later. More action was packed into less time, which gave the effect of everything being sped up.

There are many ways to overcome the inherent features of a particular technique, and these adaptations to the technique are one area we explore in the topics about each technique. It is important to think about what a technique might bring to a film and if it is complementary to the concept of the film. If it is not complementary, then how can you adjust the technique to complement your idea? Once you have your idea and the proper technique, and in our case, we are concentrating on these alternative stop-motion techniques, you need to proceed deeper into preproduction.