Stop Motion and Its Various Faces

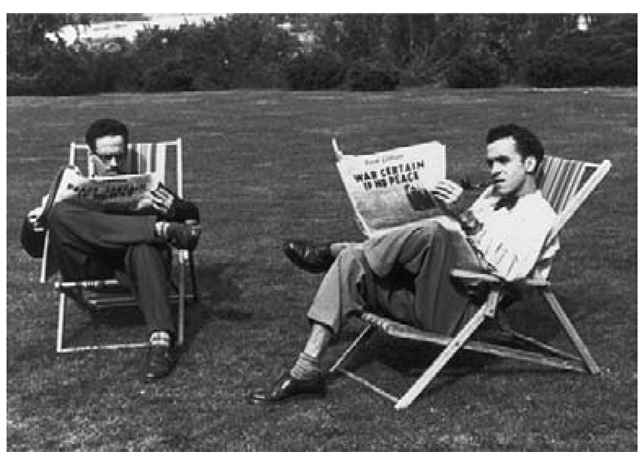

Not until 1952 did the technique of pixilation become utilized in a film that struck an international chord. Norman McLaren’s Neighbours, which featured Grant Monroe, mentioned earlier as the person who coined the term pixilation, put this technique back in the public eye.

FIG 1.5 Neighbours, directed by Norman McLaren.

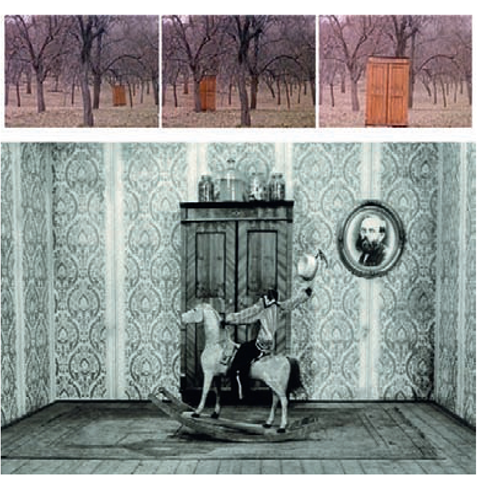

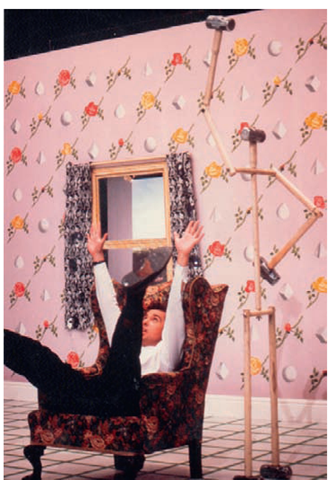

McLaren’s use of animated people and objects, dramatic action, and art direction made the technique perfect for this film. The battle between neighbors, in an extremely territorial fashion, has great humor but also a dark tone that delivers a message in an effective manner. Pixilation continued to grow after McLaren’s continued use of this technique. One of the most notable and inspirational masters of this technique is the Czech surrealist Jan Svankmajer. Although Svankmajer used puppets on occasion he also used everything else from humans to meat to household furniture as animated objects. His concentration on textural imagery and suggestive conceptual filmmaking made him stand out from all other filmmakers. His 1971 film Jabberwocky, based on a poem by Lewis Carroll, features a cabinet running through a forest, dancing clothes, maggot ridden apples, distraught dolls, and flipping puzzle parts.

FIG 1.6 A series of stills from the cabinet in Jabberwocky, directed by Jan Svankmajer 1971.

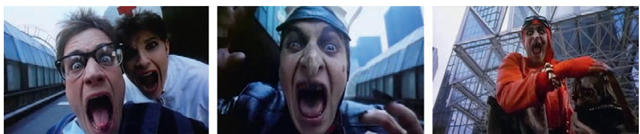

Although Svankmajer uses puppets, he mixes his animated subject matter so wildly that the photographic, textural, fast-paced editing leaves an audience feeling rather assaulted. Animators like the American Mike Jittlov, with his pixilated 1979 film Wizard of Speed and Time, and French-born Jan Kounen continued using the pixilation technique with obvious influence from their predecessor, Norman McLaren. In Kounen’s 1989 Gisele Kerozene, the use of dramatic facial makeup and costuming remind us of the faces of McLaren’s two neighbors as they start to get deeply into their fight.

FIG 1.7 Stills from Gisele Kerozene, Jan Kounen, 1989.

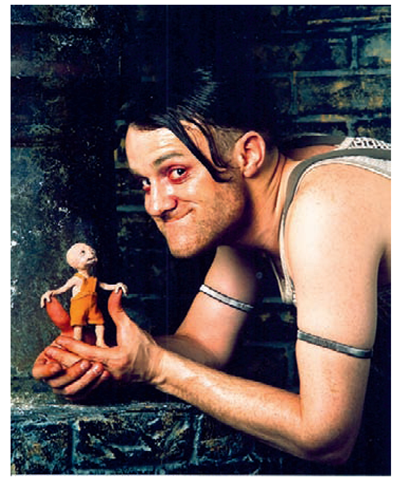

Kounen even used classic Warner Brothers cartoon animated motion when he animated people smashing into walls. Wide-angle lenses are used for exaggerated effect. Pixilation is starting to mature. The technique is no longer just a humorous or gimmicky style but a technique that can be chosen as a cinematic device. Dave Borthwick’s 1986 feature film The Secret Adventures of Thumb is a fascinating and dark film that expands the pixilation technique with a very distinctive story. Nick Upton is Thumb’s father, and he plays this role with a McLaren sense of exaggeration. This English actor holds his jaw out to maintain a particular look and refines the element of acting associated with this physically challenging technique. Controlling facial and body involuntary actions, often for hours and hours of shooting time, requires extreme control and awareness; and Upton does this quite well.

Fig 1.8 Still from The Secret Adventures of Thumb, Bolex Brothers, 1986 (Nick Upton with an exaggerated face).

Finally, it is worth noting the Peter Gabriel music video Sledgehammer. This 1986 groundbreaking animated short, produced by Limelight London and directed by Stephen R. Johnson, features the work of Aardman Animations, the Brothers Quay, and Peter Gabriel lip syncing or mimicking the words to this wonderful piece of music frame by frame and interacting with everything from fish to fruit to people to clothes and the woodwork itself. Most of these examples, including Sledgehammer, were produced and shot directly in the camera. Very few postproduction effects were added, which points out the clever and innovative approach these filmmakers used. This direct application of effects shows a resourcefulness that offers a unique look and cost-saving production.

FIG 1.9 A still from the 1986 music video Sledgehammer, written and recorded by Peter Gabriel.

Pixilation has become quite popular in film and animation programs across the country and the world. The technique is relatively inexpensive to produce and very direct in terms of the outcome. It does require proper planning like any effective use of animation, but you can get fast results and learn a lot of animation techniques by just grabbing a camera, stop-motion animation software, and objects or friends. On a professional level, there is more pixilation and mixed media out in the mainstream of our society than ever before. An example is Her Morning Elegance, directed and produced by Yuval and Merav Nathan, an Israeli couple that works in various animated techniques and genres. This music video is shot with a static camera mounted directly above a bed. A woman, a man, and objects are shot frame by frame in a controlled environment in a very stylized manner, depicting walking, movement in a subway, and swimming underwater all on top of the bed. The static background sets off the animated motion of the people, cloth, and various objects in a very satisfying manner.

FIG 1.10 Still from the music video, Her Morning Elegance, directed by Oren Lavie and Yuval and Merav Nathan.

Two other extensions of pixilation are seen in the work of Blu and PES.

Each artist uses pixilation but in very different ways. Blu works outdoors, painting walls and animating figures and objects on cityscapes. His camera work is unregistered and quite active but the dominant drawn figures in the frame maintain the focus of each shot as in his 2008 film Muto and his 2010 film Big Bang Big Boom. PES works with objects in a very controlled manner, creating events and environments out of everyday objects, as in his 2008 film Western Spaghetti. In this animated short, the simple use of candy corn vibrating frame by frame on a stove top, mimicking gas-fueled flames, sets the style that unfolds in this cooking experience. PES animated stuffed chairs having sex on a roof in New York City in his 2001 film Roof Sex.

FIG 1.11 Chairs on a roof in Roof Sex, pES, 2001.

Time-lapse photography is a form of stop motion shot in a controlled and consistent manner. The effect of the time lapse is that it speeds up time and events so the viewer can study an event from a different point of view. This perspective and different temporal perception can give us a more expanded understanding of our world and ourselves. One of the most common uses of this technique is the blossoming of a flower sped up to ten or more times the actual event. Anyone can see an hour of real time go by in just 1 second. So much more can be achieved with this approach to stop-frame photography. Not only can events be recorded at an accelerated rate but animators can use this technique to pixilate objects and people. It is critical that the time-lapse camera have an intervalometer, or timer, associated with the camera so the shutter can expose the film or digital image sensor at an even rate. The even exposure rate or shooting interval of the camera reveals the natural rate or evolution of an event in nature sped up and compressed into a short viewing time.

Once again, George Melies was a pioneer in this area. His continued experimentation with film found him exploring time-lapse photography as is seen in the 1897 Film Carrefour De LOpera (Film Crossroads of the Opera).

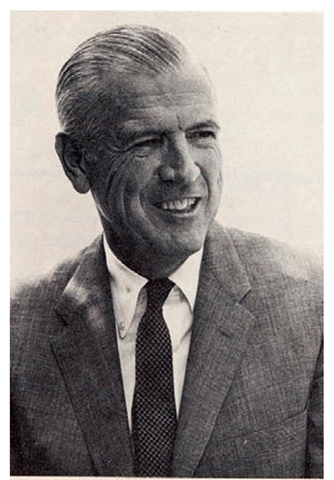

Other early uses of time-lapse photography were associated with science. Biology and various phenomenon of nature became the prime focus for this technique. The technique has the benefit of speeding up slow action and motions, giving the viewers a better understanding of how nature works. The Russian-American Roman Vishniac used it in the early twentieth century, and his interest in nature included microscopic photography and the movement of living creatures. The work of John Ott in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s became a technique landmark. Ott, an American banker by trade, was fascinated with the growth of flowers and how nature and light affected them. He cobbled together enough photography equipment controlled by an intervalometer and put his lens on various plants in his own greenhouse. His expanded knowledge of how plants grow and are affected by the environment led him deeper into this technique of stop-frame photography. He created an early motion-control machine that moved the camera increment by increment, frame by frame as the camera captured a plant’s progress over a long period of time. This movement of the camera from position A to B added a poetic element to the more scientific locked camera positions.

This inspired many filmmakers for years to come, including the rich and refined time-lapse photography of the British filmmaker David Attenborough, as illustrated in his 1995 film, The Private Life of Plants. Many sequences in this film focus on plant flytraps. The time-lapse photography of the growth and feeding habits of these plants rival any science fiction film ever made. Yet, nature provides these creatures and time-lapse photography allows us to view them with an expanded point of view.

The British Oxford Scientific Film Institute, in the 1950s and 1960s, went a long way to refining the scientific use of time-lapse photography and inspired many filmmakers and scientists like Attenborough and Ron Fricke. In the early 1980s, American filmmakers Godfrey Reggio and Ron Fricke created a feature film based around the revealing qualities of time-lapse photography. Called Koyaanisqatsi, most of the film was shot in the "four corners" of the western United States and New York City. The use of time-lapse photography is so effective that clouds can be seen as rushing currents of water and people traversing streets in New York look like pulsing blood in the veins of an urban environment.

FIG 1.12 Dr. John Ott, circa 1950.

The perspective of this film is so unlike anything we are used to seeing that it is easy to understand the message these filmmakers are creating without a word of dialog or narration. Technically this footage is superior, utilizing motion-control cameras, varied shutter speeds, natural and artificial light, and dynamic composition. The sound work of Philip Glass helps place this film in a category of its own that is unique, beautiful, and powerful. Time-lapse photography continues to be used in all sorts of commercial and educational venues. It is an effect that represents the complementary side of highspeed photography. Instead of slowing down events, it speeds them up and presents a whole new way of observing any event.

The last alternative stop-motion technique that we cover has many subcategories of its own. The one element that unifies these various subcategories is the way they are shot. Materials like sand, beads, candy, paper, photographs, and an infinite list of objects can be manipulated under a mounted camera on an animation stand, or downshooter. This is also referred to as a multiplane animation stand. All these elements can be shot in a horizontal fashion, but with a downshooter, they are treated like animation cels or drawings on a traditional animation stand. When shot this way these objects can be free of the constraints of gravity. The most developed and popular use in this area is "cutout" animation. This involves drawings, photographs, and other two-dimensional objects joined together with rivets, string, wax, or other hinging devices to simulate animated movement. Although this leans much more in the two-dimensional world, like drawn animation, technically speaking, it is a form of stop-motion or frame-by-frame manipulation. The German artist Lotte Reininger created one of the earliest examples of this form of stop motion. The Adventures of Prince Achmed was a feature film produced in 1926 using flat opaque materials like lead and cardboard. These forms were shaped and constructed to move on a flat piece of glass with lighting that came from behind the cutouts. This created a silhouette effect that was enhanced with some limited color and various background materials to give a painterly look.

FIG 1.13 a still from Aucassin and Nicolette, by Lotte Reiniger.

Cutout animation was one of the most popular techniques of animation, after drawing, for the first part of the twentieth century. It was a way to display a fair amount of detail without having to draw that detail over and over again. The Japanese utilized this approach through artists like Noburo Ofuji and Kihachiro Kawamoto. Applying individual and cultural techniques and styles to cutout animation added to the depth of this approach. Kawamoto traveled to Czechoslovakia in the early 1960s to work with Jiri Trnka in Prague, but Trnka encouraged him to pursue his own cultural history and create stories and artistic applications that were relevant to Japanese culture.

Cutout animation was a fairly popular technique, practiced by animators that worked in different mediums, including model stop-motion animation, and traditional cel or drawn animation. Auteurs in Argentina, England, Russia, Czechoslovakia, the United States, and other countries animated using back-and front-lighted cutouts, cardboard, lead, translucent color papers, illustrations, and engravings, among other materials. The films produced using cutouts tended to be figurative in nature and often had cultural and ethnic themes.

The relatively low cost of producing this technique allowed independent filmmakers and financially challenged countries to compete on the world stage in animation. The late twentieth century had several successful applications of cutout animation. Most notable was the Russian Yuri Norshtein and his film Tale of Tales, produced in 1979. This is a haunting tale of a family, community, and the effects of war. Norshtein uses drawings and cutouts, superimposed layer on layer, to create a very dreamy and often frightening memory full of atmosphere. This is a very controlled and time-consuming technique, and Norshtein is one of the masters. He continues to work today on a feature called The Overcoat, which has been over 20 years in the making.

FIG 1.14 Yuri Norshtein working on The Overcoat.

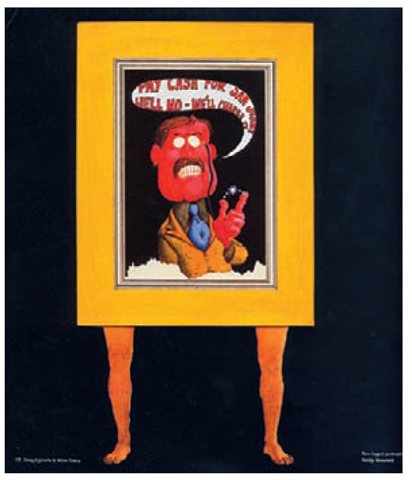

Other contributors to cutout animation include Terry Gilliam’s work in the British television series Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Gilliam, an expatriate American artist, cobbled together strange, surreal, and entertaining animated shorts for the series featuring drawings of his own and a large collection of Victorian illustrations and photographs animated together in the cutout approach. They were so offbeat and unusual that his animation became a signature part of the Flying Circus series.

FIG 1.15 Two-legged portrait of Teddy Roosevelt.

In more recent history, several American television shows started out as cutout animation but evolved into computer-generated images that simulate the cutout approach. South Park, created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone, was first conceived in cutout animation but became too difficult to produce in volume using this technique. Many more pieces of animation for television and the Internet mimic the cutout look but use computer animation for efficiency, including Blue’s Clues, JibJab, and Angela Anaconda.

These examples of cutout animation primarily use flat illustrated or photographic elements but a downshooter can also manage to hold more dimensional objects like beads, candy, clay, sand, or any other object that can fit between the shooting surface and the mounted camera. An example of this approach is from the 1988 film CandyJam, directed by Americans Joan Gratz and Joanna Priestly. It features the work of animators from around the world and is themed around candy. Several of the animators animated candy on a glass surface in patterns and figurative forms. The wonderful mix between flat and dimensional styles helps make this rich in texture and style.

Sand on glass is another popular downshooting technique mastered by the American-born Caroline Leaf. Although Leaf was born and educated in the United States, she is associated with the National Film Board of Canada, where she produced numerous films over the 1970s and 1980s and into the twenty-first century. Sand is manipulated on a flat glass surface with the camera mounted directly above the glass. The lighting comes from below the glass and the sand blocks the light from the camera, leaving a silhouetted image. The thinner the layer of sand, the more light comes through, giving the image a feathered look. There are many variations on this technique, and Leaf employs them well.

FIG 1.16 A still from The Street, directed and animated by Caroline Leaf.

We have only touched on a bit of the history and highlights of these alternative stop-motion techniques. Filmmakers have always been fascinated with the potential of creating images frame by frame to create illusions and fantasy. Although the majority of animation artists followed a more figurative and narrative approach to animation and stop motion in particular, many successful examples show less traditional, alternative uses of the medium in the nonfigurative areas. Today, artists are revisiting some of these older techniques and putting a new spin on them, with fresh ideas and technology. A real image captured by a camera has a unique and genuine appeal that is hard to deny. Computer imagery is full, fluid, and quite refined, but the imperfection and anomalies of the photographic expression of an object or person are what strikes us to the core.

The process of shooting photographic frame-by-frame films requires a certain skill set that is unique to these techniques. All the innovators mentioned in this topic have been groundbreakers. They had to take risks to experiment and use what they discovered in their process and expand on those discoveries. Many, like Dziga Vertov, were not so readily accepted in society, but their passion and drive to discover new means of expression in their filmmaking drove them forward in their frame-by-frame approaches. Pixilation, time-lapse photography, and downshooting are techniques that exemplify this approach, and we explore them in more depth in the following topics. The possibilities are expansive.