Working the Frames

We have finally come to one of the last stages in the filmmaking process: editing. We discovered that, in animation, much of this editing is done early on in the preproduction process. The animatic, which is the moving timeline of the storyboard, should be the guide for the final edit in any animated film. We claimed that animation is so labor-intensive that overshooting scenes is not an option. So, unlike live-action filmmaking, animation has done a good bit of the postproduction decision making before the last process begins. Yet, many fine details need attention at the editing stage, and this is what we will address.

Some basic principles of shooting and editing need to be examined before we get into specific frame-by-frame options for editing. When you are shooting out of sequence for a film, which is fairly common in filmmaking, it is critical to always check any already shot footage that might sit on the timeline on either end of the shot you are about to animate. You might want to shoot out of sequence because several shots have the same setup, and shooting those shots together saves a lot of production time in the setup. If you do not examine all the shots already animated on either side of your current shot, then you may miss an opportunity to match the shots for action, lighting, prop consistency, and framing. This could create a lot of trouble in the final edit. A common practice is to work with your animatic as the base edit. Each time you complete a shot, you should replace the corresponding storyboard drawing from the animatic with the final animation. This forces you to keep an eye on the bigger picture and makes sure that your cuts work together.

"If I’m playing with dialogue I have a rough measure of how long I need.

I usually shoot the movements (especially the mouths) leaving lots of held frames and then adjust the timings in the editing room."

Terry Gilliam

Terry Gilliam refers to a technique common in these alternative stop-motion techniques: the manipulation of individual frames. Oftentimes, while in the middle of a shoot, you may wonder about the length of a particular hold of an object or person. It is always best to overshoot frames and remove extra frames in the edit process. In this case, Gilliam is overshooting lip-sync frames and adjusting the timing with the sound in the edit. A tendency with novice stop-motion animators is to shoot even increments of the subject, which in the end loses any dynamic in movement. With no variation in the movement from frame to frame, the movement of an object or person is robotic. This ultimately should be addressed in the shooting process, but if you change your mind about a particular movement or action, then the edit room becomes your last chance to improve things without a reshoot. You can remove frames between key positions for speed and snappy actions, and you can repeat frames to make a hold last longer, so the audience can have a brief moment to catch up. The issue with repeating frames, as mentioned earlier, is that it is best to repeat sequential hold frames to keep the movement from freezing in place. Holding a single frame is rarely desirable. Oftentimes, using a technique referred to as rock and rolling is the best way to keep hold frames alive. You would use frame 1 of a sequence, then frame 2 and frame 3, back to 2 and 1, then back up to 2 and 3, and so forth. This way any jumps in the movement can be avoided. But, like Gilliam, you want to make sure to always shoot enough frames of a hold or certain action, if you think you might extend or cut them later in the edit. Having said this about not holding single frames, I have seen some successful short pixilated films that utilize the held single frame, like the Argentinean Juan Pablo Zaramella’s Hotcorn. His dramatic facial expressions and good timing works very well with the frozen held frames, and the contrast of movement and held frames make this animated short fresh and snappy. There are very few hard and fast rules in animation, and it often takes certain creative types to break any existing "rules" to forge new and interesting ground.

FIG 11.1 Sequence of three images from Hotcorn, directed by Juan Pablo Zaramella

FIG 11.2 "Rock and rolling" frames for a hold.

One final solution to holding frames is a postproduction effects solution.

If you need a hold in an unexpected area and you only have one frame to hold, then duplicating that frame in postproduction is possible. Later, in After Effects, you can add a "grain and noise" filter to that single frame. These duplicate frames with added grain do not feel quite so static and out of place in running time. But, randomly placing holds in the edit process often does not work, because when the movement begins again, there probably will be no ease-in of the action in the next frame, so the animation will jump. You must examine your sequence and plan carefully when you add holds.

Jeff Sias, from Handcranked Productions, describes another way to deal with making your animation more dynamic in the editing process:

"Editing programs also have the ability to ‘ramp’ speeds and have variable time changes with an editing graph. This will allow you to really tweak a particular motion if necessary. Also related to this is the idea of ‘frame blending,’ as in, if you stretch a shot out in time, you can have the program try to create new in-between frames, either by blending frames together or by tracking pixels and actually creating brand new frames. The latter option can create strange and undesirable digital artifacts, but it works well on normal and slow moving objects if you only lengthen the shot by 200-300% or less."

Here is an exercise to give you an idea of the ability you have in the edit to improve your timing in an animated action in a frame-by-frame film. The one important element that you must consider when using this technique is what else is happening in the background of the shot you are frame manipulating. When you pull frames to add dynamic to a foreground object or person, how does the elimination of those frames affect the background or secondary action in the overall animation composition? Complexity in the overall composition with multiple objects or people may prevent you from pulling and adding frames in the editing process.

Chapter 8 has an exercise where you animate a person along a wall frame by frame with eases for approximately 1 second of animation. There are still holds at the head and tail of the shot. You need to create this footage if you have not already shot it. The playback rate is 30 fps. Create an image sequence from these shots and convert it into a Quicktime movie in Quicktime Pro. As mentioned before, Quicktime Pro is an extremely helpful investment. You can also import this footage into an editing program, like Final Cut or Adobe Premiere. You can do this by either creating a Quicktime movie of the footage or importing the individual frames from a folder after setting the "still/freeze duration" to 00:00:00:01 under Editing in the User Preferences area of Final Cut.

Once you have the frames on the timeline, use the filmstrip mode so you can see the individual frames. Then enlarge the timeline, so you can clearly see each frame. In the original exercise, there was a 15-frame hold at the head. I want you to go eight frames into that hold and "rock and roll" frames 9, 10, and 11 three times (i.e., frames 8, 9, 10, 11, 10, 9, 10, 11, 10, 9, 10, 11, 10, 9, 10, 11, 12). Once you have completed this, move into the movement frames. You have 15 forward movements, including eases shot on "twos" Move into those frames and remove the two frames from the fourth movement forward, the sixth movement forward, the eighth movement forward, the ninth movement forward, the eleventh movement forward, and finally the thirteenth movement forward. Remember that you need to remove two frames for each of these movements, because you shot on "twos" Finally, make sure you remove any unwanted gaps between frames by right-clicking on the gap in Final Cut. Once you have completed this, render the footage and export it as a Quicktime movie.

When you compare the two Quicktime movies (the original and edited footage), you will see the effect of the rock and roll hold extension and the ability to change the animation dynamically in editing. This type of edit manipulation goes all the way back to the Cinemagician, Georges Melies.

Impossible Perfection

There is no perfect solution to any one film. Rather, the imperfection gives each piece its unique character, yet we, as artists, have a tendency to keep refining our artistic expression until we run out of time. Each film is a learning experience, even for the more advanced filmmaker, and it is important to take the lessons of each film, close the book on the old film, and move on. This liberating approach allows you to continue to grow and experiment, and that is the essence of this kind of filmmaking. Having said this, you can do much more to refine each filmic experience in the edit.

If you have been shooting with a dslr still camera, the chances are that your images are large enough to scale up in size without losing resolution, even for high definition playback. This means that you can simulate simple camera moves in postproduction either in After Effects or a similar program or in Final Cut. I prefer actual camera moves to simulated moves, because real camera moves give you a genuine perspective change in the image that the postproduction move does not. The postproduction move just moves across the surface of the image, it does not penetrate it like a real camera move. Sometimes, a postproduction simulated move can be effective; for example, if you want a handheld camera feel or are shooting flat images like photographs and you want to push in (and there would be no perspective change anyway), or if you just want to keep a scene alive with a subtle track. A digital move can augment a real physical move but generally postproduction moves done in these programs are effective if they are extreme or subtle but less successful in the ground between.

Mixing live-action elements with single-frame footage takes a lot of planning. We covered match lighting and object/person interaction in the previous chapter, but another element of this kind of composite work is adjusting the colors to match. If your white balance option was not set correctly in the shooting stage, then the edit is the time to correct this oversight. Thinking about an interesting color palette or plan is important in the planning stage, but it is the postproduction work that fine-tunes the differences that may occur in shooting. The bottom line is that you need to have good footage to begin with but there is some latitude in color correction whether you do it in Final Cut Pro, Photoshop, or After Effects. It is best to identify one establishing shot and color correct that shot to the best of your ability. All of the following shots should be matched to that default color-corrected master scene. There is the possibility of changing the overall color palette in the postproduction process, but usually, this should have been explored in the preproduction stage. Your attitude and ideas evolve during a film’s development, so allowing yourself a chance to play with the colors in color correction is worth the time. You might change the image to black and white or a sepia tone; or shift the contrast, saturation, brightness, or color scheme; or add filters to view your film in another perspective. Keep track of all the changes and their corresponding filter measurements, so you can duplicate a look you discovered and want to apply to other parts of your film. You can accomplish this by saving your filters and effects settings as "presets." This allows you to reapply the same exact effect to any shot at any time.

File Management

Another important practice that needs to be sorted out in the preproduction stage is the naming convention for all your files. If you establish a good file-naming system and stick with it, then the editing and postproduction work become much more manageable. You can do this in several ways; here is a system I used on my most recent film, Off-Line.

Title abbreviation = OL Scene = sc Take = t

Frame number = f Effects = e Final frames = F

You must consider the full range of scenes in your film and the maximum amount of frames in any scene; that number, in the tens or hundreds, has to be carried out throughout.

This would be a final frame with effects. None of my shots had more the 999 frames in them, and my film had 99 scenes or fewer. This may seem like a long naming convention, but you can easily identify any frame in or out of place at any time.

There might be several drafts of effects that you apply to your frames, and you might have to consider temporarily adjusting your naming convention to give you an idea where you are in the effects process. For example, if you have color corrected and cleaned out some rigs but have not composited additional images on your frames, then you might put a d after the e in your naming convention. The d would represent a certain "draft" or pass of the effects, so you could write " …ed1" at the end and leave that in the overall effects folder until you finish the effects of those frames. When you complete the effects, just label the frame " …e," and perhaps it will be finished at that point, so you can complete the naming convention with an F at the end. The important thing to remember is that you need to set up this naming convention early and keep it consistent for you and any crew working with you. Once again, Jeff Sias weighs in about naming conventions. "It is important for After Effects to ‘see’ a complete image sequence. If there are any missing numbers in the sequence, AE will assume that the frame is missing and replace it with a warning frame. You can also use a utility program like Automator (on the Mac) to batch rename the files in a sequence. Adobe Bridge also does a good job of batch renaming, but Automator is faster."

Playback

We touched on frame rates when we explored pixilation. It is always best to decide and commit to a frame rate when you animate your material. There are so many things to consider with your playback rate, like how fluid do you want your animation; how much time you have to shoot or animate; and how much finesse and control do you need in the movement of your object, person, or image?

I like to shoot 2 frames per move at a playback rate of 30 frames per second. I can also take one picture per movement and have a playback rate of 15 frames per second. It is possible to slow down or speed up playback rates in editing programs like Final Cut Pro but I do not recommend speeding up or slowing down a shot more than 15%, especially slowing down a shot. It often does not look as good and the animation can have a more staccato look, which can be distracting. It is worth experimenting with frame rates to establish the playback pace and feeling that you want. Keep in mind that After Effects can process your frames with "frame blending," which essentially creates in-between frames when you slow down your footage. This can make a big difference in the playback.

One old trick that many filmmakers use effectively is playing footage backwards. It can have a very interesting effect. Images or objects can appear to assemble themselves or perform unnatural movements. If you follow the normal laws of physics like recoil, inertia, and momentum with the idea of playing a scene backwards, then you will have a very successful effect. Another reason for a reverse playback would be if you are animating to a final position or graphic that would very difficult to achieve animating frame by frame forward. In this case, you shoot the final frame in its predetermined and finessed position, then you take it apart frame by frame, then reverse the playback.

FIG 11.3 An animated image that needs art direction and could be animated backwards.

FIG 11.4 William Kentridge playing his footage backwards to have artwork appear to assemble itself with the guidance of Kentridge, from Invisible Mending.

A habit to consider when shooting any animation that will help in the editing process is shooting "handles." This basically means that you should shoot an extra 5 to 10 frames at the head and tail of each shot, even though you might have a very closely timed animatic. These extra frames provide more options on the actual cut point and give you more footage if you have to vary the speed of your playback.

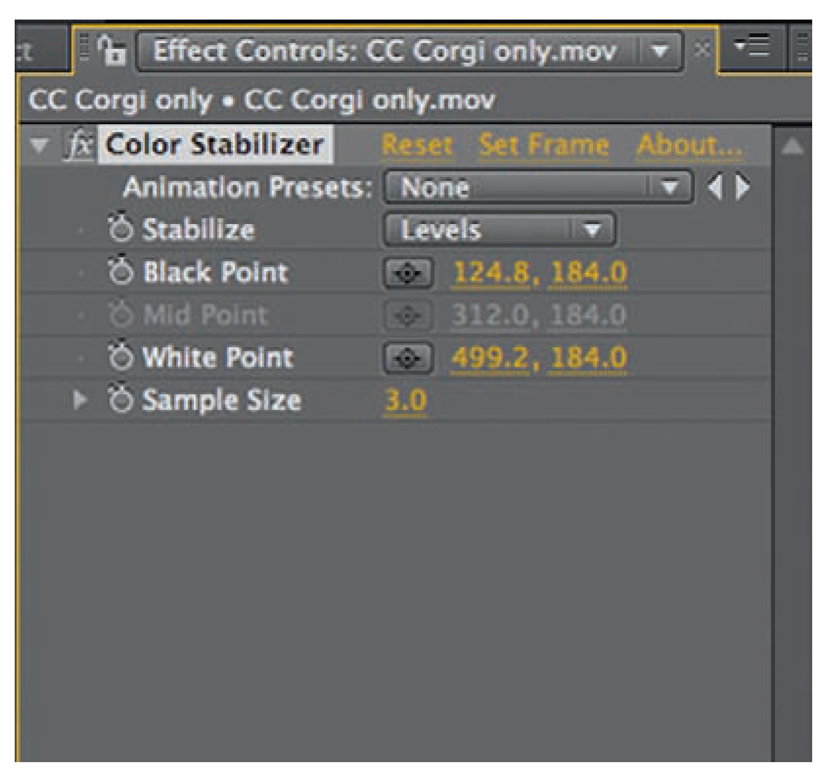

One issue that arises from different sources is flicker or fluctuation in the overall animated image during playback. We discovered in Chapter 5, about cinematography, that small variations in the iris of certain lenses or variations in the power source that powers your lights could cause these minor exposure fluctuations. There are some solutions to this flicker effect. These postproduction solutions do not resolve overall fluctuations due to moving shadows and shifting light sources but even out overall image variation. It is always best to first use appropriate lenses and filtered power if you want a nice even exposure on all your shots, but if you do not get it, then it is time to turn to a program like After Effects. If you open up Effects ^ Color Correction ^ Color Stabilizer and look for the Set Frame button in the Attributes area, then you can establish the color reference frame. You can set the reference frame through brightness adjustment, levels, or curves. You may have to set a new reference frame, depending on the activity in the frame or if there is a camera move. Breaking up the shot into multiple sections and reassembling the sections can solve any difficulties of having to set a new reference frame. This is not a perfect solution but can help. More effective After Effects plug-ins do the job, but they are more expensive as solutions to overall image flutter. Filters and names change with each upgrade so I advise searching "flicker" or "fluctuation" in the Help or Search menu of any forum or program that deals with these kinds of issues.

FIGE 11.5 The Color Stabilizer menu in After Effects.

Editing is an important and deep art form in the filmmaking process.

Many books are written on the subject, including Michael Ondaatje’s The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, Murch’s In The Blink of an Eye, and On Film Editing by Edward Dmytyrk. Animation is one form of filmmaking, and it should be treated in a manner similar to live-action editing when it comes to cutting pace and flow. Using techniques like "cutting on the action," dissolves for a passage of time, "jump cutting" for a jarring effect, and dynamic pacing in the overall cut are critical to all filmmaking, even frame-by-frame animation.