Live Action and Single Framing

We already mentioned how important it is to exaggerate images and actions with some of the alternative stop-motion techniques. Time-lapse photography usually does not include acting or contrived scenarios, but it still requires a sense of drama if you want to capture an audience’s attention. Choosing the right subject matter that reveals real transformation over time makes this technique effective. Setting the camera so that the composition is dynamic becomes important to a time-lapse study or any form of filmmaking. This can be done by utilizing foreground and background elements in the same shot, thinking about the use of diagonal lines in the composition to lead the viewer deeper into the composition, placing the camera in an unusual point of view, playing with scale, and including an interesting color and lighting palette. An artist also has to consider how a composition changes over the course of a shot. Knowing where your camera will move and what will transform in front of the camera is critical to maintaining great dynamic compositions. It is usually more interesting to have a subject enter the camera composition from a diagonal direction than directly in from the side. There are many ways to build interest in your animation, and many of these principles apply equally to live-action filmmaking.

FIG 8.1 A series of shots showing dynamic composition elements (foreground/background, diagonal lines, unusual POV, and color palette).

FIG 8.2 Using scale for a dramatic effect in Alice by Jan Svankmajer, 1987.

Good art direction is critical to any film, but two elements are even more important. The first element and the one that everything rotates around is the idea. We touched on this in preproduction, and Focal Press has several topics that cover this immense subject. The next element is performance. Having good actors can make or break any film, and the same is true with animation. When it comes to animation, you, the animator, are really the actor and what you do with your inanimate object, person, or artwork in terms of performance is pivotal to the success of your film. Live-action filmmakers know that there are two kinds of realities. First, there is the way life unfolds from one event to the next. We live this reality every day here on Earth. Sometimes, it is exciting and usually it is not. Life is full of dull tasks and activities that are necessary to our survival. When we go to see a film or a stage production, we do not want to be reminded of these mundane tasks and realities. We are interested in the compressed, interpreted high and low points and emotional expressions of an event. We want the icing without the cake. This is true for animation as much as any other sequential art form. One example of this reality in animation is the use of the everyday walk. Walks can be very revealing about an individual. When we observe a walk, we take cues about the energy level, determination, and attitude of an individual. If this is essential to understanding that character, then animating a walk is an important element in the storytelling process. Normally we do not need to see a character walk from point A to point B. We want the filmmaker just to get us to point B and move the story along. We are interested in the emotion and highlights of the story, not the everyday realities like a long walk. There are some exceptions to this premise, but for the most part, this is the dramatic reality that animation should consider.

PES describes his approach to his 2003 pixilated film Roof Sex. Even though he is approaching this film in a documentary form, there is still a great sense of drama and compressed and interpreted shot sequences.

"Would the idea of two chairs having sex conceptually work as a drawn animation? Yes, definitely. In CGI? Yes, definitely. But, in my opinion, the execution gains power when using real objects on a real location … it’s much, much closer to real life and it hits a more absurdist note. I believed that stop-motion was the best technique for Roof Sex because my intention was to treat the idea like a documentary. I fancied myself spying on these two specific chairs that escaped from their owner’s apartment one day, and almost as a voyeur, I recorded what they had done for posterity. There are no cartoony sound effects; everything was done with an eye to being as believable as possible. As in much of my work, there is humor to be found in the earnest—almost documentarian—approach to the fantastic. For me, photographic images combined with absurdist, yet oddly logical, ideas are like rubbing two rocks together to create a spark."

Subtle and Broad Performance

Time-lapse filming usually does not include performance, except by the natural occurrence of an event.There can be some subtlety in performance in some of the downshooting techniques, like sand animation. This more refined movement can be achieved with small controlled moves in the sand or clay and can even be attained by the use of dissolves from one frame to the next. Yet, on the whole, these alternative frame-by-frame techniques are broader and less refined than other forms of animation, like drawn and computer-generated animation. These last techniques allow more control, and they are often used in this way.

Generally, like action on the stage and in early film, broad acting is assigned to the wide shot. The figures or objects are smaller in the frame (like seeing the stage from the back of the theater), so the action has to be bold and broad. Close-ups are usually reserved for the more subtle and refined movements of an individual or object. In pixilation, these more subtle forms of acting are more difficult to achieve because of the constant movement of a human that is caught frame by frame. The constant moving in and out of registration or exact placement of the person in the frame makes this technique broader and less subtle. Broad exaggerated expressions help distract the viewer from the constant vibration even in the close-ups. Using "freeze frames" is not a solution to the constant vibration of pixilation. This approach kills the continuity of a pixilated shot and pulls the audience right out of their suspended reality. You can repeat two or three similar frames to keep the vibration going although if this is done for too long the viewer can see the cycle of frames. Extreme control on the subject/actor’s part is the only way to achieve some sort of subtlety in pixilation. It recalls Lindsay Berkebile’s term "chaotic life amongst silence" Controlled breathing and eye movements along with rig support for heads and hands help maintain stability and potential subtlety without breaking the special energy prevalent in pixilation.

There is the potential for more subtlety in object animation and downshooting, because the objects are inanimate and do not live and breathe (at least not until they are projected). The subtle or broad approach, style, and purpose is up to the director. If we examine the work of PES again we see a lot of wonderful and controlled movement, like in the underwater world of The Deep. Chains are moved with gentle S-curve gestures that mimic a piece of kelp waving underwater and calipers bob up and down like jellyfish as pliers (fish) surge forward, all underwater (or so it appears). These beautifully animated tools create that illusion because of the subtle yet dynamic choices the animators make in the movement.

Fig 8.3 image from The Deep.

Joan Gratz produces beautiful full-detail paintings and uses metamorphosis to move from one to the next, frame by frame. These can be dissolved from one image to the next or they can be step printed. Step printing means that each frame has a low-opacity layer of the previous and following frames on it. Step printing is also referred to as step weaving. This adds to the flow and subtlety in her animation. As Joan puts it,

"In Mona Lisa Descending a Staircase, images of the human face are subtly transformed to communicate the graphic style and emotional content of key artworks of the 20th century"

We covered broad facial exaggerations that many artists like McLaren and Kounen utilize, but it is important to remember that dynamic movement also makes a huge difference in the performance. Certainly by using "eases" you build in acceleration and deceleration, but there is much more to movement than this single dynamic principle. This is the essence of animation. There is so much to discover in this area that even veteran animators like me are constantly trying new combinations of movement for their dramatic effect. Here is an exercise that helps illustrate two types of movement and their effect.

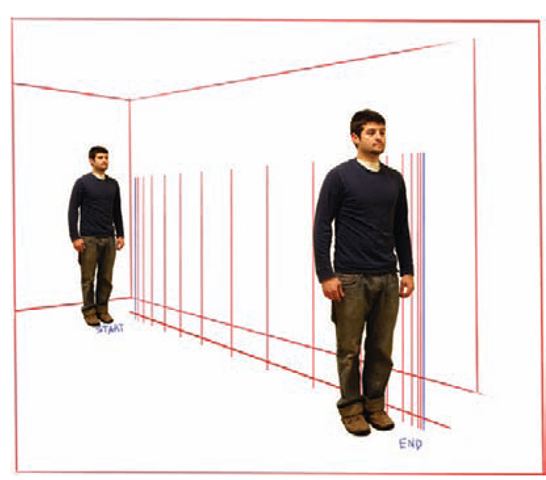

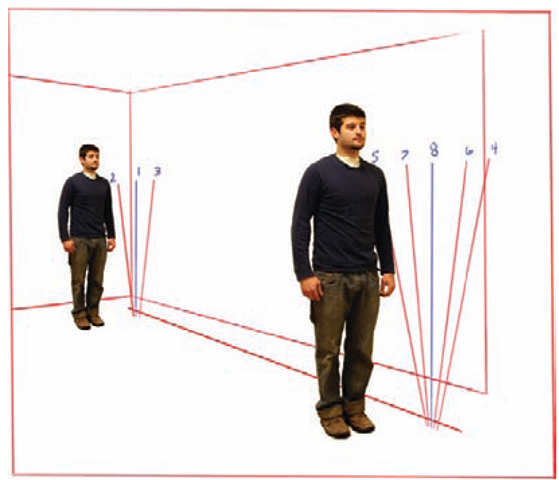

You need a digital camera (still or video) and a tripod. If you have a laptop to control the camera, then bring that along, but this exercise can be done without the capture software. You need a flash card in your digital still camera to capture frames that you will download into a computer after the exercise, if you have no computer on the set. You also need a person, but an object will work. You can shoot this exercise outdoors or indoors, but you need about 20 feet of space to move in. Try to find a background with very little visual detail, like a wall. If you are outdoors then try to execute this exercise where the light is as even as possible. If you are indoors you need broad soft light, like overhead lights. Set the camera slightly off-center from your subject, which will stand 20 feet away from the camera (frame left) near the wall. Mark off 15 forward positions for your subject to move toward the camera, ending frame right. Try to include some simple ease-ins and ease-outs. Remember that these are the increasing and decreasing increment movements that are a natural part of the physics of any movement. Shoot 15 still frames of your subject in the far position, then have the person move up to the next forward mark (toward the camera) and shoot 2 frames. Continue this pattern until the subject rests near the camera (including those ease-outs), then shoot 15 frames of hold at the end. That is the first reference.

Try this again but this time hold for 15 frames at the front, lean your subject back a bit in anticipation (shoot 2 frames), then one small move forward (shoot 2 frames), then move your subject all the way up to the last position (close to the camera), leaning forward (2 frames), then 1 frame leaning back, 1 frame leaning forward (not as far as the first time), and so forth. Settle your character out and shoot 8 frames of hold. The playback should be 30 frames per second. This is the "snap" effect and makes your subject look like a vertical diving board. It is very dramatic and adds a fun dynamic to your shot.

FIG 8.4 A shot of the first ease movement animation setup.

FIG 8.5 A shot of the "snap" animation setup.

Reference Film and the Cartoon

One of my first jobs was working for the "claymation" studios of Will Vinton.

A small crew of us spent many years animating characters for an animated feature. Many of us were relatively new to animation, so one of the techniques that Vinton incorporated was making a live-action reference film of all the voice actors as they read their lines in the sound studio. All of the animators would take the appropriate clip of live-action reference film into our set and view it on a 16 mm viewer as we animated. It was a great way to learn how movement works, and there were actions that the voice actors incorporated in their performance under the direction of Vinton that we were able to translate into stop motion animation. This gave the director more unified control over the performance of the animation. The more successful animators used this reference only as a bouncing board for animating, incorporating more dramatic expressions, holds, and actions in their puppets. We used this same technique using digital video cameras more recently when I animated on Aardman Animation’s Creature Comforts America.

The important point is that even the most experienced animators can rely on reference footage. It is a wonderful learning tool, but one that is to be interpreted. Animation is best when it does something that live action cannot do. Pixilation has the look of live action when you view the individual frames, but it is the relationship of those frames, one to the next, that makes this art form interesting. When you start playing with the incrementation and variation of the placement of the human subject in the frame, you enter into the realm of the moving cartoon. This approach is exemplified in the pixilation work of McLaren, Kounen, Jittlov, and PES and can be realized by trying out the exercise just mentioned.

One technique that many pixilation filmmakers promote is the use of the wide-angle lens. This can add dramatic effect to a cartoon that can be humourous. These lenses range from 12 mm to 35 mm in focal length and usually are best when they are prime, or single focal length, lenses. The wider lenses are most effective, but are also expensive to purchase. Using an 18 mm lens on human faces can be very dramatic, humorous, and even bordering on the grotesque. When you use a wide lens like a 24 mm, 28 mm, or 35 mm focal length on animated objects, it helps bring you down into that object’s world and scale. Using a wide-angle lens for close-ups when the lens is set at eye level to the object helps make the image appear larger than it actually is, because the lens makes the background recede faster than a longer lens. The foreground subject looks larger than the background, giving it a grand appearance. This close proximity of the lens and camera to the object can make it difficult for an animator to get to the animated objects, but the effect can be worth it. The only area where wide-angle lenses can be a problem is in the downshooting mode. Wider lenses require wider background shooting planes, and this can be impractical. Most downshooting stands are made for 35 mm and longer lenses, like 50 mm, 85 mm, 105 mm, etc. Any dramatic quality like distortion has to be incorporated into the artwork. As mentioned previously, longer lenses like 85 mm, 105 mm, and 135 mm have an inherent shallower depth of field than wider lenses, so it is important to consider this if you have artwork on a downshooter background that needs to be in focus. Oftentimes, a lens in the 35 mm to 50 mm range works well on downshooters.

Look in the Eyes

Audiences have to care about your characters. Whether your performance is broad or subtle, stylized or naturalistic, photographic in nature or fabricated from nuts and bolts (literally), the characters have to have a humanity to them.

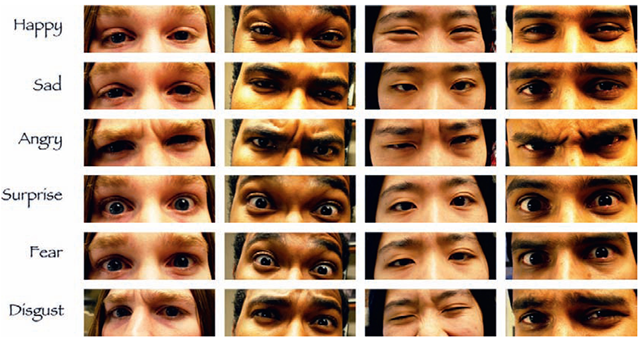

It is critical that the audience has empathy and a vested interest in what your character will do next. If you do not explore these emotional avenues, then you will lose your audience. Allowing your characters to appear to think, have an emotional response, and react with action gives them a kind of life that we understand. So much of that thinking and emotion can be read in the eyes. It is critical to bring the camera close and allow enough time for your character to think. This makes them real in the eyes of the audience. The close-up is certainly the animator’s friend. These shots can have a huge impact on the story and require the least amount of work. A few blinks, the darting of the eyes or a slight squint can carry a scene with great emotional power. We do understand the attitude of a person from his or her body language. Is this individual energetic, depressed, or nervous? We can read this immediately, because the body is large and consistent in its form, but the eyes confirm the true emotional state. Since we cannot hear the character think, we become more involved in the film by starting to project our thoughts on that individual, based on the situation and our understanding of the character.

We may be right or wrong. It does not matter. What is important is that we participate in the storytelling through our projections and caring, and that is good filmmaking. This focus on the eyes explains why early film actors and stage actors would wear heavy eye makeup to highlight their eye expressions. The audience in the auditoriums needed to see what their eyes were saying.The other source is a wonderful 1928 silent film by Danish-born Carl Dryer, The Passion of Joan of Arc, where the whole emotional storyline is expressed through the actors’ eyes.

FIG 8.6 A shot of a series of eyes in the six universal emotional expressions.

Paul Ekman, a prominent psychologist, showed and proved that there are several universal emotional displays across all cultures. These include happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, fear, and disgust. All audiences understand these expressions and displays of emotion immediately, because we all share them, and they are revealed through the eyes as much as any other means. These expressions and emotions should be used and exaggerated in frame-by-frame animation for a greater dramatic effect.