Clamping Down on Your Wireless Home Network’s Security

Well, that’s enough of the theory and background, if you’ve read from the beginning of this topic. It’s time to get down to business. In this section, we discuss some of the key steps you should take to secure your wireless network from intruders. None of these steps is difficult, will drive you crazy,or make your network hard to use. All that’s required is the motivation to spend a few minutes (after you have everything up and working) battening down the hatches and getting ready for sea.

The key steps in securing your wireless network, as we see them, are the following:

1. Change all the default values on your network.

2. Enable WPA.

3. Close your network to outsiders (if your access point supports this).

A virtual private network encrypts all the data that you send and receive through your computer’s network connection by creating a secure and encrypted network tunnel that runs from your computer to an Internet gateway (which could be in your office’s network or run by a service provider on the Internet). If you really wanted to be as secure as possible, you could use a VPN from a service provider such as Witopia (www. witopia.net) to encrypt your traffic at home too. The added benefit of a VPN, beyond security, is anonymity. To folks on the Internet, you will "look" like you’re surfing the Internet from that Internet gateway and not your home — which makes it harder for folks to track your comings and goings on the Internet. A VPN isn’t required to have a secure Wi-Fi network, but if you have one and your WEP or WPA security is broken by a bad guy, your communications will be secured by another layer of encryption.

Hundreds of different access points and network adapters are available. Each has its own unique configuration software. (At least each vendor does; and often different models from the same vendor have different configuration systems.) You need to RTFM (Read the Fine Manual!). We give you some generic advice on what to do here, but you really, really, really need to pick up the manual and read it before you enable security on your network. Every vendor has slightly different terminology and different ways of doing things. If you mess up, you may temporarily lose wireless access to your access point. (You should still be able to plug in a computer with an Ethernet cable to gain access to the configuration system.) You may even have to reset your access point and start over from scratch. Follow the vendor’s directions (as painful at that may be). We tell you the main steps you need to take to secure your network; your manual gives you the exact line-by-line directions on how to implement these steps on your equipment.

Most access points also have some wired connections available — Ethernet ports you can use to connect your computer to the access point. You can almost always use this wired connection to run the access point configuration software. When you’re setting up security, we recommend making a wired connection and doing all your access point configuration in this manner. That way, you can avoid accidentally blocking yourself from the access point when your settings begin to take effect.

Getting rid of the defaults

It’s incredibly common to go to a Web site like Netstumbler.com, look at the results of someone’s Wi-Fi reconnoitering trip around their neighborhood, and see dozens of access points with the same service set identifier (SSID, or network name; refer to next topic). And it’s usually Linksys because Linksys is the most popular vendor out there (though NETGEAR, D-Link, and others are also well represented). Many folks bring home an access point, plug it in, turn it on, and then do nothing. They leave everything as it was set up from the factory. They don’t change any default settings.

Well, if you want people to be able to find your access point, there’s nothing better (short of a sign on the front door) than leaving your default SSID broadcasting out there for the world to see. In some cities, you could probably drive all the way across town with a laptop set to Linksys as an SSID and stay connected the entire time. (We don’t mean to just pick on Linksys here. You could probably do the same thing with an SSID set to default, the D-Link default, or any of the top vendors’ default settings.)

When you begin your security crusade, the first thing you should do is to change all the defaults on your access point. You should change, at minimum, the following:

- Your default SSID

- Your default administrative password

If you don’t change the administrative password, someone who gains access to your network can guess at your password and end up changing all the settings in your access point without your knowing. Heck, if they want to teach you a security lesson — the tough love approach, we guess — they could even block you out of the network until you reset the access point. These default passwords are well known and well publicized. Just look on the Web page of your vendor, and we bet you can find a copy of the user’s guide for your access point available for download. Anyone who wants to know them does know them.

When you change the default SSID on your access point to one of your own making, you also need to change the SSID setting of any computers (or other devices) that you want to connect to your LAN. To do this, follow the steps we discuss in this part’s earlier topics.

This tip really falls under the category of Internet security (rather than airlink security), but here goes: Make sure that you turn off the Allow/Enable Remote Management function (it may not be called this exactly) if you don’t need it. This function is designed to allow people to connect to your access point over the Internet (if they know your IP address) and do configuration stuff from a distant location. If you need this turned on (perhaps you have a home office and your IT gal wants to be able to configure your access point remotely), you know it. Otherwise, it’s just a security hole waiting to be opened, particularly if you haven’t changed your default password. Luckily, most access points have this function set to Off by default, but take the time to make sure that yours is set to Off.

Enabling encryption

After you eliminate the security threats caused by leaving all the defaults in place (see the preceding section), it’s time to get some encryption going. Get your WPA (or WEP) on, as the kids say.

We’ve already warned you once, but we’ll do it again, just for kicks: Every access point has its own system for setting up WPA or WEP, and you need to follow those directions. We can give only generic advice because we have no idea which access point you’re using.

To enable encryption on your wireless network, we suggest that you perform these generic steps:

1. Open your access point’s configuration screen.

2. Go to the Wireless, Security, or Encryption tab or section.

We’re purposely being vague here; bear with us.

3. Select the option labeled Enable WPA or WPA PSK (or, if you’re using WEP, the one that says Enable WEP or Enable Encryption or Configure WEP).

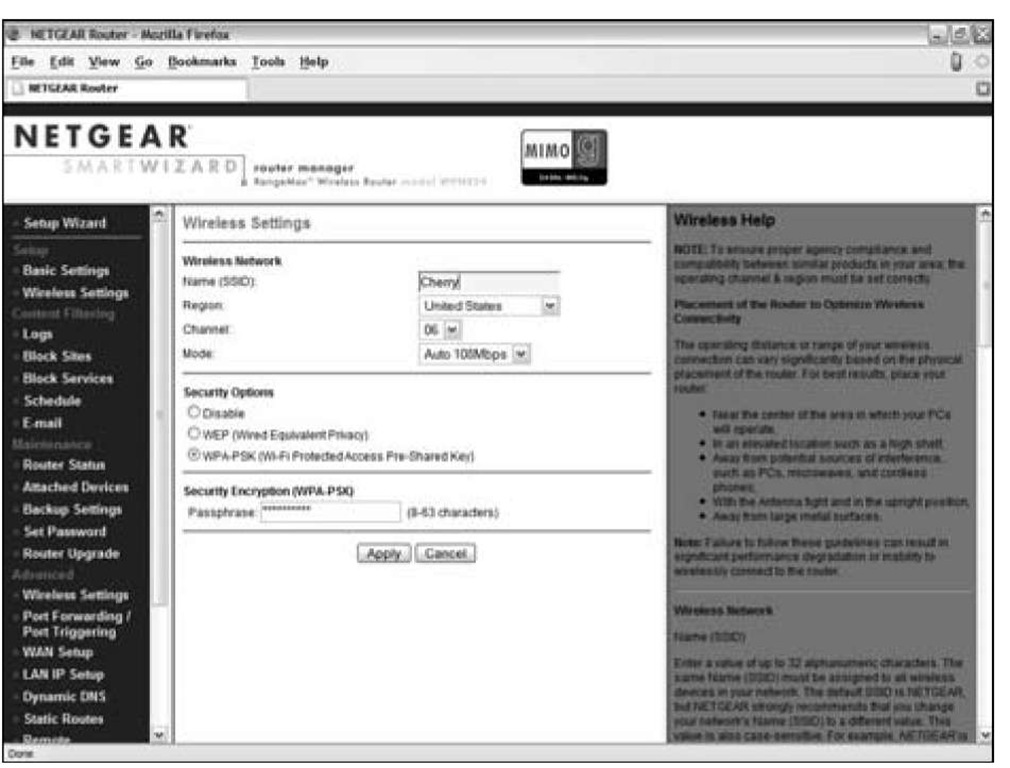

You should see a menu similar to the one shown in Figure 9-1. (It’s for a NETGEAR access point or router.)

4. If you’re using WEP, select the check box or pull-down menu option for the appropriate WPA key length for your network. If you’re using WPA, skip this step.

We recommend 128-bit keys if all the gear on your network can support it. (See the earlier section "How about a bit more about WEP?" for the lowdown on WEP keys.)

Figure 9-1:

Setting up WPA on a NETGEAR access point.

5. For WPA, create a passphrase that will be your network’s shared secret. For WEP, create your own key if you want (we prefer to let the program create one for us):

a. Type a passphrase in the Passphrase text box.

b. Click the Generate Keys (or Apply or something similar) button.

Remember the passphrase. Write it down somewhere, and put it someplace where you won’t accidentally throw it away or forget where you put it.

Whether you create your own key or let the program do it for you, a key should now have magically appeared in the key text box. Note: Some systems allow you to set more than one key (usually as many as four keys). In this case, use Key 1 and set it as your default key by using the pull-down menu.

Remember this key! Write it down. You’ll need it again when you configure your computers to connect to this access point.

Some access points’ configuration software doesn’t necessarily show you the WEP key you’ve generated — just the passphrase you’ve used to generate it. You need to dig around in the manual and menus to find a command to display the WEP key itself. (For example, the Apple AirPort software shows just the passphrase; you need to find the Network Equivalent Password in the Airport Admin Utility to display the WEP key — in OS X, this is in the Base Station menu.)

For WEP, the built-in wireless LAN client software in Windows XP numbers its four keys from 0-3 rather than 1-4. So, if you’re using Key 1 on your access point, select Key 0 in Windows XP.

6. Click OK to close the WPA or WEP configuration window.

You have finished turning on WPA or WEP. Congratulations.

Can we repeat ourselves again? Will you indulge us? The preceding steps are very generic. Yours may vary slightly (or, in rare cases, significantly). Read your user’s guide. It tells you what to do.

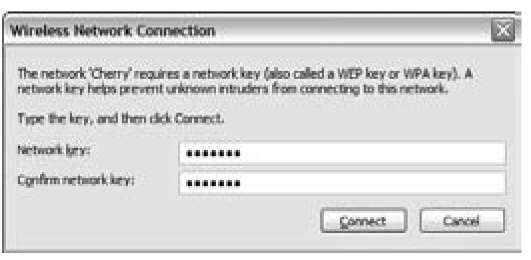

After you configure WPA or WEP on the access point, you must go to each computer on your network, get into the network adapter’s client software,turn on WEP, and enter the passphrase or the WEP key. Typically, you find an Enable Security dialog box containing a check box to turn on security and one to four text boxes for entering the key. Simply select the check box to enable WEP, enter your key in the appropriate text box, and then click OK. Figure 9-2 shows this process using Windows XP and its built-in Wireless Zero Configuration client.

Figure 9-2:

Setting up WPA using the Windows XP Wireless Zero Configuration.

Closing your network

The last step we recommend that you take in the process of securing your wireless home network (if your access point allows it) is to create a closed network — a network that allows only specific, predesignated computers and devices onto it. You can do two things to close down your network, which makes it harder for strangers to find your network and gain access to it:

Turn off SSID broadcast: By default, most access points broadcast their SSID out onto the airwaves. This makes it easier for users to find the network and associate with it. If the SSID is being broadcast and you’re in range, you should see the SSID on your computer’s network adapter client software and be able to select it and connect to it — that is, assuming you have the right WEP key, if WEP is configured on that access point. When you create a closed network, you turn off this broadcast so that only people who know the exact name of the access point can connect to it.

You can find access points even if they’re not broadcasting their SSIDs (by observing other traffic on the network with a network sniffer program), so this security measure is an imperfect one — and no substitute for enabling WPA. But it’s another layer of security for your network. Also, if you’re in a situation where you will have lots of people coming into your home and wanting to share your connection, you may not want to close off the network, so you’ll need to balance convenience for your friends against the small exposure of a more open network.

Set access control at the MAC layer: Every network adapter in the world has assigned to it a unique number known as a Media Access Control (MAC) address. You can find the MAC address of your network adapter by looking at it (it’s usually physically printed on the device) or using software on your computer:

• Open a DOS window and use the winipcfg command in Windows 95, 98, or Me or the ipconfig/all command in Windows NT, 2000, or XP.

• Look in the Network Control Panel or System Preference on a Mac.

Dealing with the WEP hex and ASCII issues

One area that is consistently confusing when setting up a WEP key — and often a real pain — is the tendency of different vendors to use different formats for the keys. The most common way to format a key is to use hexadecimal (hex) characters. This format represents numbers and letters by using combinations of the numbers 0-9 and the letters A-F. A few other vendors use ASCII, which is simply the letters and numbers on your keyboard.

Although ASCII is an easier-to-understand system for entering WEP codes (it’s really just plain text), most systems make you use hexadecimal because it’s the standard. The easiest way to enter hex keys on your computers connecting to your access point is to use the passphrase we discuss in the section "Enabling encryption." If your network adapter client software lets you do this, do it! If it doesn’t, try entering the WEP key you wrote down when you generated it (it’s probably hexadecimal). If that doesn’t work either, you may have to dig into the user’s manual and see whether you need to add any special codes before or after the WEP key to make it work. Some software requires you to put the WEP key inside quotation marks; other software may require you to put an 0h or 0x (that’s a zero and an h or an xcharacter) before the key or an h after it (both without quotation marks).

With some access points, you can type the MAC addresses of all the devices you want to connect to your access point and block connections from any other MAC addresses.

Again, if you support MAC layer filtering, you make it harder for friends to log on when visiting. If you have some buddies who like to come over and mooch off your broadband connection, you need to add their MAC addresses as well, or else they cannot get on your network. Luckily, you need to enter their MAC addresses only one time to get them "on the list," so to speak — at least until you have to reset the access point (which shouldn’t be that often).

Neither of these "closed" network approaches is absolutely secure. MAC addresses can be spoofed (imitated by a device with a different MAC address, for example), and hidden SSIDs can be seen (with the right tools), but both are ways to add to your overall security strategy.

Taking the Easy Road

We hope that the preceding section has shown you that enabling security on your wireless network isn’t all that hard. It’s straightforward, as a matter of fact. But a percentage of folks are always going to want things to be even easier (count us in that group!). So the Wi-Fi Alliance and Wi-Fi equipment manufacturers have developed a new standard (yeah, another standard!) called Wi-Fi Protected Setup, or WPS.

WPS (in its early days of development WPS was called Simple Config) is an additional layer of hardware or software or both built into Wi-Fi APs, routers, and network adapters that makes it easier for users to set up WPA in their network and easier to add new client devices to the network.

WPS is still pretty new (the Wi-Fi Alliance specification for the system was approved in early 2007), and not all Wi-Fi equipment on the market supports the system. But based on what WPS brings to the table, it’s an attractive system that we suspect will be made available more widely over time.

So what does WPS do? Well, it essentially automates the authentication and encryption setup process for WPA by using one of two methods:

A PIN: All WPS certified equipment will have a PIN (personal information number) located on a sticker. When a WPS certified router or AP detects a new wireless client on the network, it will prompt the user to enter this PIN — either through the management software or Web page for the router, or directly on the router itself using an interface (such as an LCD screen) located on the router. If the correct PIN is entered, the network will automatically configure WPA and allow that device to join the network. That’s all there is to it!

A button: The other mechanism for using WPS is called PBC (or push button configuration). As the name implies, a button (either a physical button or a virtual one on a computer screen or LCD display) is used — there’s a button on both the AP/router and the client hardware. When the router or AP detects a new Wi-Fi client wanting to join the network, the buttons are activated — if you want to grant the new client permission to join the network, you simply press the buttons on both the router/AP and the client; configuration is automatic at this point.

WPS takes the drudgery out of setting up WPA and makes the process pretty much foolproof. WPS doesn’t change the actual level of security you’re getting on your network — all it does is turn on WPA (WPA2, to be exact). One thing to keep in mind about WPS is that you need to have WPS capabilities on both ends of the connection — the AP/router and the network client — to use the system, but you can still use the old-fashioned manual configuration process described in the preceding section to add non-WPS capable gear to your network.

As WPS becomes more widespread, the Wi-Fi Alliance folks have a few more tricks up their sleeves to make things even easier. These tricks come in the form of two additional ways of using WPS:

NFC: NFC (near field communications) is an extremely short-range (think centimeters, not feet) radio system (similar, and related, to the RFID tags now in use in warehouses and other logistics systems). With NFC, you would simply put the WPS client and AP/router in very close proximity and they’d automatically configure network access and security. Pretty cool.

USB: The final method for using WPS involves USB flash drives (the little stick memory cards so many folks carry around these days. WPS can allow a user to simply "carry" the network credentials to a client on a flash drive — plug the flash drive into the AP/router and then into the network client, and configuration is automatic.

These final two methods are optional in the WPS standard — the first two are mandatory (found in all WPS certified devices).

As we mention at the outset, WPS is still pretty darned new, but you can see the growing list of WPA compliant products at the Wi-Fi Alliance Web site at www.wi-fi.org/wifi-protected-setup/ (just scroll down to the link titled Products Certified for Wi-Fi Protected Setup).

Going for the Ultimate in Security

Setting up your network with WPA security keeps all but the most determined and capable crackers out of your network and prevents them from doing anything with the data you sent across the airwaves (because this data is securely encrypted and appears to be just gibberish).

But WPA has a weakness, at least the way it’s most often used in the home: the preshared key (your shared secret or passphrase) that allows users to connect to your network and that unlocks your WPA encryption.

Your preshared key can be vulnerable in two ways:

If it’s not sufficiently difficult to guess (perhaps you used the same word for your passphrase as you used for your network’s ESSID): You would be shocked by how many people do that! Always try to use a passphrase that combines letters (upper- and lowercase is best) and numbers and doesn’t use simple words from the dictionary.

If you’ve given it to someone to access your network and then they give it to someone else: For most home users, this isn’t a big deal, but if you’re providing access to a large number of people (maybe you’ve set up a hot spot), it’s hard to put the genie back in the bottle when you’ve given out the passphrase.

802.1x: The corporate solution

Another new standard that’s become quite popular in the corporate Wi-Fi world is 802.1x. This isn’t an encryption system but, rather, an authentication system. An 802.1x system, when built into an access point, allows users to connect to the access point and gives them only extremely limited access (at least initially). In an 802.1x system, the user could connect to only a single network port (or service). Specifically, the only traffic the user could send over the network is your login information, which is sent to an authentication server that would exchange information (such as passwords and encrypted keys) with the user to establish that he or she was allowed on the network. After this authentication process has been satisfactorily completed, the user is given full access (or partial access, depending on what policies the authentication server has recorded for the user) to the network.

Neither of these two circumstances is usually a problem for the typical home — WPA-PSK (WPA Home) is more than sufficient for most users. But if you want to go for the ultimate in security, you may consider using an AP (and wireless clients) that supports WPA Enterprise.

WPA Enterprise uses a special server, known as a RADIUS server, and a protocol called 802.1x (see the nearby sidebar, "802.1x: The corporate solution"), which provide authentication and authorization of users using special cryptographic keys. When a RADIUS server is involved in the picture, you get a more secure authorization process than the simple shared secret used in WPA Home. You also get a new encryption key created by the RADIUS server on an ongoing basis — which means that even if a bad guy figured out your key, it would change before any damage could be done.

You can use a hosted RADIUS service on the Internet. Such services charge a small monthly fee (about $5 per month) and let you use a RADIUS server that’s hosted and maintained in someone’s data center. All you need to do is pay your monthly bill and follow a few simple steps on your access point and PCs to set up RADIUS authentication and WPA Enterprise.

You need to have an AP that supports WPA Enterprise — check the documentation that came with yours because not all APs support it.

Several services provide WPA Enterprise RADIUS support. An example is the SecureMyWiFi service offered by Witopia (www.witopia.net). SecureMyWiFi provides security for one AP and as many as five users for free, and charges for additional users.

802.1x is not something we expect to see in any wireless home LAN any time soon. It’s a business-class kind of thing that requires lots of fancy servers and professional installation and configuration. We just thought we would mention it because you no doubt will hear about it when you search the Web for wireless LAN security information.