Connecting to the Internet

When you get right down to it, the reason why most people build wireless networks in their homes is to share their Internet connection with multiple computers or devices that they have around the house. That’s why we did it — and we bet that’s why you’re doing it. We have reached the point in our lives where a computer that’s not constantly connected to a network and to the Internet is seriously handicapped. We’re not really even exaggerating much here. Even things you do locally (use a spreadsheet program, for example) can be enhanced by an Internet connection; for example, in that spreadsheet program, you can link to the Internet to do real-time currency conversions. These days it’s not uncommon to be using an online application such as Google Docs and Spreadsheets, working simultaneously with a handful of other people on a spreadsheet through your browser and Internet connection.

What a wireless network brings to the table is true whole-home Internet access. Particularly when combined with an always-on Internet connection (which we discuss in just a second) — but even with a regular dial-up modem connection (yes, some people still use modems) — a wireless network lets you access the Internet from just about every nook and cranny of the house. Take the laptop out to the back patio, let a visitor connect from the guest room, or do some work in bed. Whatever you want to do and wherever you want to do it, a wireless network can support you.

A wireless home network — or any home network, for that matter — provides one key element. It uses a NAT router (we describe this item later in this section) to provide Internet access to multiple devices over a single Internet connection coming into the home. With a NAT router (which typically is built into your access point or a separate home network router), you can not only connect more than one computer to the Internet but also simultaneously connect multiple computers (and other devices, such as game consoles) to the Internet over a single connection. The NAT router has the brains to figure out which Web page or e-mail or online gaming information is going to which client (PC or device) on the network.

Not surprisingly, to take advantage of this Internet-from-anywhere access in your home, you need some sort of Internet service and modem. We don’t get into great detail about this topic, but we do want to make sure that you keep it in mind when you plan your network.

Most people access the Internet from a home computer in one of these ways:

Dial-up telephone connection Digital subscriber line (DSL) Cable Internet

Fiber-optic service (such as Verizon’s FiOS service) Satellite broadband DSL, cable, fiber-optic, and satellite Internet services are often called broadband Internet services, which is a term that gets defined differently by just about everyone in the industry. For our purposes, we define it as a connection that is faster than a dial-up modem connection (sometimes called narrowband) and is always on. That is, you don’t have to use a dialer to get connected, but instead you have a persistent connection available immediately without any setup steps necessary for the users (at least after the first time you set up your connection).

Broadband Internet service providers are busily wiring neighborhoods all over the United States, but none of the services are available everywhere. (Satellite is available almost everywhere. But, as with satellite TV, you need to meet certain criteria, such as having a view to the south, that is, facing the satellites, which orbit over the equator.) Where it’s available, however, growing numbers of families are experiencing the benefits of always-on and very fast Internet connectivity.

In some areas of the country, wireless systems are beginning to become available as a means of connecting to the Internet. Most of these systems use special radio systems that are proprietary to their manufacturers. That is, you buy a transceiver and an antenna and hook it up on your roof or in a window. But a few are using modified versions of Wi-Fi to provide Internet access to people’s homes. In either case, you have some sort of modem device that connects to your AP via a standard Ethernet cable, just like you would use for a DSL, fiber-optic, cable modem, or satellite connection.

For the purpose of this discussion of wireless home networks, DSL, fiberoptic, and cable Internet are equivalent. If you can get more than one of these connections at your house, shop around for the best price and talk to your neighbors about their experiences. You might also want to check out www.broadbandreports.com, which is a Web site where customers of a variety of broadband services discuss and compare their experiences. As soon as you splurge for a broadband Internet connection, the PC that happens to be situated nearest the spot where the installer places the DSL, fiber-optic, or cable modem is at a distinct advantage because it is the easiest computer to connect to the modem — and therefore to the Internet. Most DSL and cable modems connect to the PC through a wired network adapter card. FiOS uses a device called a router to connect to the PC via the same wired network adapter card. The best way, therefore, to connect any computer in the home to the Internet is through a home network.

You have two ways to share an Internet connection over a home network:

Software-based Internet connection sharing: Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Mac OS X enable sharing of an Internet connection. Each computer in the network must be set up to connect to the Internet through the computer connected to the broadband modem. The disadvantage with this system is that you can’t turn off or remove the computer connected to the modem without disconnecting all computers from the Internet. In other words, the computer connected to the modem must be on for other networked computers to access the Internet through it. This connected computer also needs to have two network cards installed — one card to connect to the cable/DSL modem or FiOS router and one to connect to the rest of the computer on your network via an AP or switch.

Cable, DSL, or FiOS router: When you connect to one of these services, the router used between the broadband modem and your home network allows all the computers on the network to access the Internet without going through another computer. The Internet connection no longer depends on any computer on the network. These routers are also

DHCP — and in most cases NAT — servers and typically include switches. In fact, the AP and the modem can also include a built-in router that provides instant Internet sharing all in one device.

As we mention earlier in the topic, nearly all APs now available for home networks have a built-in broadband router.

Given the fact that you can buy a router (either as part of an access point or a separate router) for well under $60 these days (and prices continue to plummet), we think it’s false economy to skip the router and use a software-based, Internet connection sharing setup. In our minds, at least, the advantage of the software-based approach (very slightly less money up front) is outweighed by the disadvantages (requiring the PC to always be on, lower reliability, lower performance, and a much bigger electric bill each month).

Both software-based, Internet connection sharing and cable or DSL routers enable all the computers in your home network to share the same network (IP) address on the Internet. This capability uses network address translation (NAT). A device that uses the NAT feature is often called a NAT router. The NAT feature communicates with each computer on the network by using a private IP address assigned to that local computer, but the router uses a single public IP address in data it sends to computers on the Internet. In other words, no matter how many computers you have in your house sharing the Internet, they look like only one computer to all the other computers on the Internet.

Whenever your computer is connected to the Internet, beware the potential that some malicious hacker may try to attack your computer with a virus or try to break into your computer to trash your hard drive or steal your personal information. Because NAT technology hides your computer behind the NAT server, it adds a measure of protection against hackers, but you shouldn’t rely on it solely for protection against malicious users. You should also consider purchasing full-featured firewall software that actively looks for and blocks hacking attempts, unless the AP or router you purchase provides that added protection.

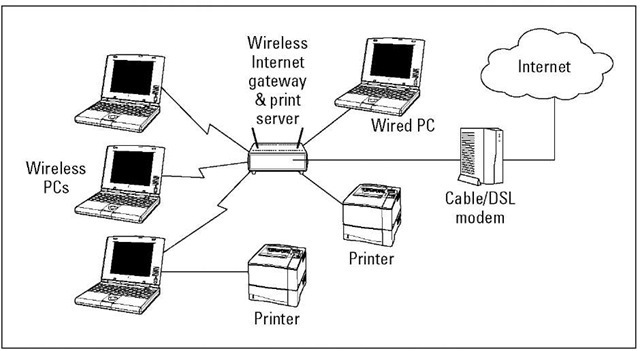

As we recommend in the "Choosing an access point," section earlier in this section, try to choose an AP that also performs several other network-oriented services. Figure 4-4 depicts a wireless home network using an AP that also provides DHCP, NAT, a print server, and switched hub functions in a single stand-alone unit. This wireless Internet gateway device then connects to the DSL or cable modem, which in turn connects to the Internet. Such a configuration provides you with connectivity, sharing, and a little peace of mind, too.

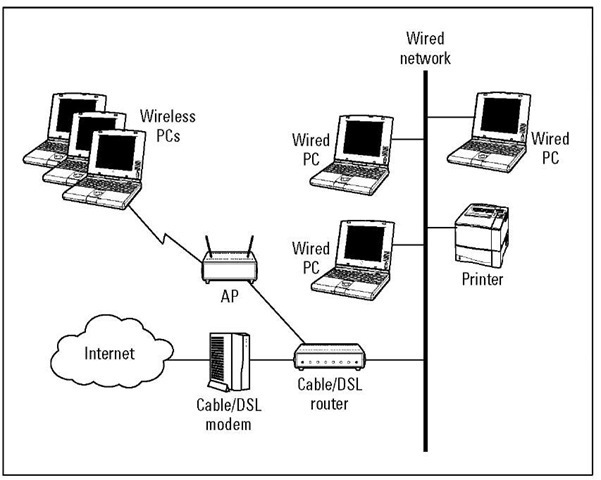

If you already have a wired network and have purchased a cable or DSL router Internet gateway device without the AP function, you don’t have to replace the existing device. Just purchase a wireless access point. Figure 4-5 depicts the network design of a typical wired home network with an AP and wireless stations added. Each PC in the wired network is connected to the cable or DSL router, which is also a switch. By connecting the AP to the router, the AP acts as a bridge between the wireless network segment and the existing wired network.

Figure 4-4:

Go for a wireless gateway that combines AP, DHCP, NAT, print server, and switched hub functions in one unit.

Figure 4-5:

A wired home network with an AP and wireless stations added.

Budgeting for Your Wireless Network

Assuming that you already own at least one computer (and probably more) and one or more printers that you intend to add to the network, we don’t include the cost of computers and printers in this section. In addition, the cost of subscribing to an ISP isn’t included in the following networking cost estimates.

Wireless networking hardware — essentially APs and wireless network adapters — is available at a wide range of prices. With a little planning, you won’t be tempted to bite on the first product you see. You can use the following guidelines when budgeting for an AP and wireless network adapters. Keep in mind, however, that the prices for this equipment will certainly change over time, perhaps rapidly. Don’t use this information as a substitute for due diligence and market research on your part.

Pricing access points

At the time this topic was written, wireless access points for home use ranged in price from about $35 (street price) to around $100.

Street price is the price at which you can purchase the product from a retail outlet, such as a computer-electronics retail store or an online retailer. The dreaded suggested retail price is often higher.

Multifunction access points that facilitate connecting multiple computers to the Internet — wireless Internet gateways if they contain modem functionality and wireless gateways or routers if they don’t — range in price from about $50 to $150.

You need to budget roughly $60 for an 802.11g AP and about $160 for an 802.11n AP. If you have some older wireless equipment that you still want to use, you can find a combination a/b/g/n AP for about $350. Keep in mind that these combination APs, while great for leveraging your existing equipment, force your entire network to work at the slowest device speed on that network. (Frankly, if you still have any a or b equipment, it’s time to retire it and just plan on purchasing new n equipment. It’s more than worth it for the increased range and speed your wireless network will gain.)

The differences in price between the cheapest APs and the more expensive models generally correspond to differences in features. For example, APs that support multiple wireless standards are more expensive than similar APs that support only one standard. Similarly, an AP that is also a cable or DSL router costs more than an AP from the same manufacturer that doesn’t include the router feature.

You may run across APs from well-known companies, such as Cisco (not from Cisco’s Linksys brand, but labeled as "Cisco" APs) and 3COM, that are significantly more expensive than the devices typically purchased for home use. These "industrial-strength" products include advanced features and come with management software that enables corporate IT departments to efficiently and securely deploy enterprise-level wireless networks. The underlying technology, including the speed and the range of the wireless radios used, are essentially the same as those used in the economically priced APs in most wireless home networks. But the additional features and capabilities of these enterprise-level products save IT personnel countless hours and headaches rolling out dozens of APs in a large wireless network.

Pricing wireless network adapters

Wireless network adapters range from $25 to $125, depending on whether you purchase 802.11a, b, g, or n technology and whether you purchase a PC Card, USB, or internal variety of adapter.

Like APs, wireless network adapters that support multiple standards are somewhat more expensive than their counterparts. An 802.11a/b/g/n card costs between $45 and $100. Most notebook computers sold are equipped with at least b/g wireless built into them, and you can order them with a/b/g/n internal cards for about the same price as buying a quad standard card. You can find the Linksys WLAN-WPC4400N quad-standard card at a street price of $105 as we went to press. Wow!

Looking at a sample budget

Table 4-2 shows a reasonable hardware budget to connect a laptop computer, and a home desktop computer, and a cable Internet connection to an 802.11n wireless home network.

Table 4-2 An 802.11n or g Wireless Home Network Budget

|

Item |

Price Range |

Quantity Needed |

|

Access point |

835-8125 |

1 |

|

Wireless network adapters |

$25-8100 |

2 |

|

Network cable |

810-820 |

1 |

|

Cable or DSL modem (optional) |

$75-8100 |

1 |

Planning Security

Any network can be attacked by a persistent hacker, but a well-defended network discourages most hackers sufficiently to keep your data safe. However, it’s easier for a hacker to gain access through the air to a wireless network than to gain physical access to a wired network, making wireless networks, and even home networks, more vulnerable to attack. Because a Wi-Fi signal is a radio signal, it keeps going and going and going, like ripples in a pond, in a weaker and weaker form until it hits something solid enough to stop it. Anyone with a portable PC, wireless network adapter, and an external antenna in a van driving by your house, or even a neighbor with this equipment, has a reasonable chance of accessing your wireless network. (Such skullduggery is known as war driving.).

‘ Internet security: Any Internet connection — especially always-on broadband connections, but dial-up connections, too — can be vulnerable to attacks arriving from the Internet. To keep your PCs safe from the bad folks (who may be thousands of miles away), you should turn on any firewall features available in your AP or router. Some fancier APs or routers include a highly effective kind of firewall (a stateful packet inspection [SPI] firewall), but even just the basic firewall provided by any NAT router can be quite effective. You should also consider installing antivirus software as well as personal firewall software on each PC or Mac on your network for an extra level of protection.

Airlink security: This is a special need of a wireless home network. Wired networks can be made secure by what’s known as physical security. That is, you literally lock your doors and windows, and no one can plug into your wired network. In the wireless world, physical security is impossible (you can’t wrangle those radio waves and keep them in the house), so you need to implement airlink security. You can’t keep the radio waves from getting out of the house, but you can make it hard for someone to do anything with them (like read the data they contain). Similarly, you can use airlink security to keep others from getting onto your access point and freeloading on your Internet connection. The primary means of providing airlink security — and advances are on the way — is called WPA2 (Wi-Fi Protected Access). You absolutely should use WPA2 to preserve the integrity of your wireless home network.