A popular hobby called geocaching uses your GPS receiver to track r " down plots of small prizes hidden around the globe. GPS stands for Global Positioning System, and it can be used for more than simply finding your way out of the forest.

The second use is a more practical one. You can use GPS coordinates in genealogy research, both for finding cemeteries (and even specific gravestones) and your ancestors’ old homesteads, schools, churches, and other sites.

Seeking and Hiding with Geocaching

GPS is not only about using the technological equivalent of bread crumbs to find your way out of the forest. It also helps provide the basic navigational tools for geocaching, helping you pinpoint within feet the location of hidden caches that others have left for you to find.

When you’ve mastered the seeking, you may want to try the hiding part. You can create your own caches, maybe right in your backyard, that others can seek. There are even groups and Web sites dedicated to this hobby. Here are some popular geocaching Web sites:

♦ www.geocaching.com

♦ www.navicache.com

♦ www.terracaching.com

♦ www.earthcache.com

Check these out, lurk in their communities, and see which one is most exciting for you.

Playing it safe while playing

Having fun shouldnt lead to forgetting about good old common sense. Consider these things before heading off:

✓ Travel in pairs.

✓ Let someone know where you’re going if you go out to look or hide a cache.

✓ Carry ID, water, and a flashlight if you’re hiking.

✓ Make sure you get permissions to hide a cache on property if it’s not yours.

✓ Make sure you know what the park rules are for hiding things.

✓ Follow your instincts, and don’t do something if your gut is saying not to.

Nabbing the cache

Given the choice, you probably would rather nab cash. But geocaching leads to its own treasures, many of them you keep while others you take to the next cache location and exchange for something else. You can do this on and on, traveling across the United States and other countries (but mind the oceans, lest you find yourself with some wet cache).

For those who love technology, the outdoors, and a good quest, it’s a perfect hobby. It’s a little like a modern-day version of scouting, where you might have earned an orienteering badge for your skills with a map and compass. Now you’re using your map, compass, and GPS navigational skills. You can do it with friends and family; you breathe the clean air of mostly remote areas and improve your navigational skills for the day you might need them. (On the other hand, staying inside is safer and dryer. But I’m assuming you like the outdoors.)

In most instances the hidden caches are tucked away in a hidden location in a public place. Don’t expect to be digging for buried treasure in someone’s yard — if you do, you’re probably looking in the wrong place, and you’re likely to get arrested, to boot.

You don’t need an expensive GPS receiver for geocaching. An inexpensive model that’s $75 or even less is enough to get you going. Later, if you want a better GPS receiver that allows you to carry pictures and music and stuff, you always can spend a little more money ($150 to $200) for an advanced model.

You can find nearby caches by searching on the one of the Web sites listed above. At most such sites, you can search by ZIP code, state, country, and other variables. Once you find a cache you want to find, www.geocaching.com, for example, has some suggestions for hunting it down:

♦ Research the cache location. Buy a topographical map for remote cache locations. Use services like Google Maps (maps.google.com) or MapQuest (www.mapquest.com) to get driving directions for more easily accessible ones. Google Maps even has street level views of many locations, so you can familiarize yourself with the terrain in advance.

♦ If you’re familiar with the area, navigate there using mostly the readings from your GPS unit. The site www.geocaching.com doesn’t recommend this for first-time hunters. However, you may need to use a combination of all three strategies to find a cache. Bringing along a compass is a good idea, too.

♦ Drive as close to the cache location as you can. When you get within 300 feet, check your GPS receiver’s margin of error. It could be between 25 and 200 feet. The smaller the error, the more you can rely on your receiver’s reading. For the last 30 feet or so, circle the area to find the cache. For higher error rates, the circle is larger.

♦ When you find the cache, at least write your name in the enclosed log book. If you want to take an item from the cache and replace it with another, that’s great, too. This is all done under the honor system, of course. You’re not supposed to find the cache, take all the loot, and run off for an early retirement.

♦ When you leave your car, mark a waypoint on your GPS receiver. This way, you can find your way back to the car. Otherwise, you may need to wait for the next person who finds the cache, so they can lead you back to civilization.

Hiding the bounty

Once you have mastered the art and science of geocaching, you may want to try your hand at hiding your very own cache.

As for goodies, you can put just about anything in your cache. Yes, even cash — which would make you a very popular person indeed on the geo-caching circuit! Many caches contain inexpensive toys, CDs, and any other knickknacks you can imagine and that fit into the container used in the cache. Some people even include one-time-use cameras, asking all the finders to take a photo of themselves (and, of course, then leave the camera for the cacher).

The site www.geocaching.com makes these recommendations for hiding your own cache:

♦ Research the location. Look for someplace that may require some hiking, rather than an easy-to-find place close to well-traveled areas where someone may discover the cache accidentally.

♦ Prepare your cache. Your best bet is a waterproof container. You can place the actual items inside sealable plastic bags like those you use for sandwiches. Include a log book (small spiral notebook) and pen or pencil so seekers can record their find. Consider including a goodie that finders can take with them, and asking them to leave something behind, via a note in the cache container.

♦ Hide the goods. This is where you use your GPS receiver. Get the cache’s coordinates by taking a waypoint reading. For better accuracy, you should average the waypoints. If you’re using a low-end GPS model, this may require taking a waypoint up to ten times — you take a waypoint and then walk away, returning to do another one — and then finding the average waypoint measurement. This average is what you write on your container and in the log book, keeping a copy for the next cache you find.

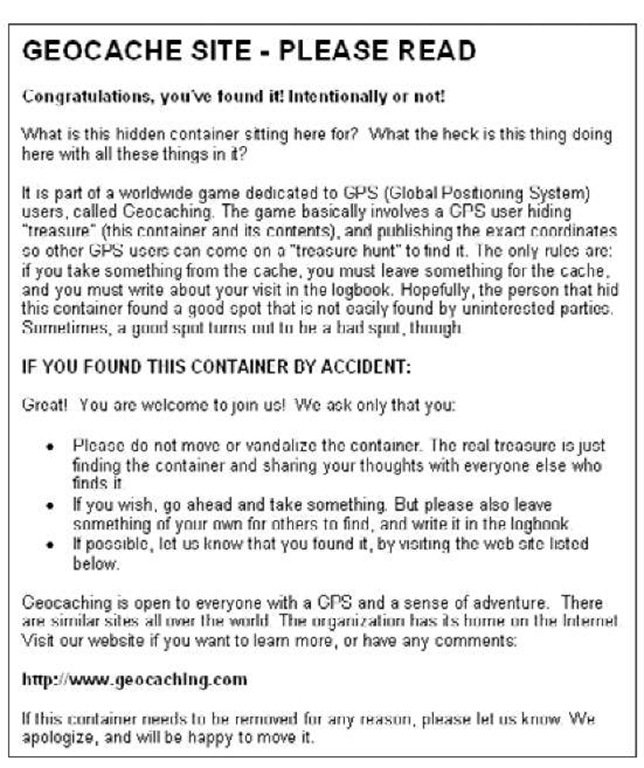

♦ Leave a note. Figure 3-1 shoes a typical geocache note.

♦ Report the cache. This involves filling out an online form on www. geocaching.com or another site. Information includes cache type, size, coordinates (of course!), overall difficulty and terrain ratings, a description, and optionally, hints.

Letterboxing: Geocaching sans batteries

What do you get if you take geocaching and substitute the GPS receiver with a compass? Letterboxing, a low-tech version of geocach-ing. And in this case, letterboxing has nothing to do with black bars on your TV set.

Instead of taking a trinket and leaving one, as you do in geocaching, letterboxing involves leaving your mark at every treasure location by stamping a log book with your own customized rubber stamp. You use another rubber stamp, stored in the cache box, to stamp your own book, like a passport.

If you wake up one Saturday morning and find your GPS receiver’s batteries are dead, a similar hobby awaits you. That is, if you’re handy with a compass.

You can read more about letterboxing at www. letterboxing.org.

Figure 3-1:

A copy of a letter you can leave in your cache box.

Finding Your Ancestors

GPS receivers can help you find your way, plot your course, and always let you know where you stand in the world. One thing it can’t do is help you find your soul. Believe me, if it could, I’d be in better shape.

Enough about lost souls. I have something pretty close to a soul, and that’s discovering my past by tracking down where my ancestors have tread. Even if you know where deceased relatives lived, it’s often difficult to find their old homesteads.

A very grave matter

Speaking of souls, you can use your GPS receiver to find burial sites. Some kind people have already logged the latitudinal and longitudinal positions of some cemeteries and share them with others on a Web site called The U.S. GeoGen Project (www.geogen.org).

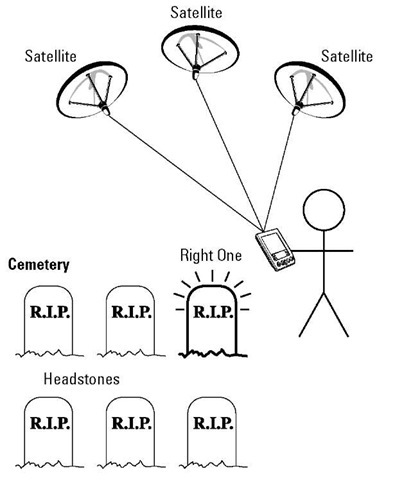

In many cases, it’s an even more difficult task to find old cemeteries, some of which aren’t as preened and tended to as those where our closest relatives rest. They may be in heavily wooded areas. Or, worst of all, vandals or developers may have tipped over or removed headstones so that you’re not even sure that what you’re visiting is a cemetery. If you have a map that lists the cemetery, have jotted down its longitude and latitude coordinates, and are heading there with a GPS receiver, you have a much better chance of actually finding it, like the person shown in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2:

Your GPS receiver can help you find an ancestor’s grave or homestead.

The original author of the first edition of this topic enlisted his adventuresome mother in a quest for a great-grandfather’s grave. They knew the cemetery, but not the location of the gravestone.

The author had the cemetery’s name, so I bet you’re thinking the rest was easy. Far from it. It was a large cemetery. There were thousands of gravestones, many of them flat against the ground so you could see them only after walking up to each and every one. And just finding the cemetery wasn’t easy.

Now imagine you have the GPS coordinates for the cemetery and that, maybe from another genealogist’s efforts, you even have the latitude and longitude of the actual grave. Now that’s something! Imagine the time you’d save. Even with GPS readings that have a margin of error of 20 feet or so, you have narrowed down the search considerably.

GPS technology isn’t going to help you find these sites unless you know they are places to look for family headstones.

Once you have a good idea of which cemeteries are good bets, either because they are close to where ancestors lived or are located on the family land, you can use maps and other tools to find the coordinates. From there, it’s a matter of using your GPS navigational skills to reach each one and check them out.

In addition to the U.S. GeoGen Project’s Web site mentioned earlier, a good place to look for coordinates of cemeteries is the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). The GNIS contains information about nearly 2 million U.S. physical and cultural geographic features. Many of these include associated latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates to enter into your GPS receiver to help you find them.

Here’s how you do a quick search of the GNIS:

1. Point your browser at http://geonames.usgs.gov/.

The GNIS home page appears.

2. On the top, click Search Domestic Names (if you are looking for U.S. landmarks).

A query form appears.

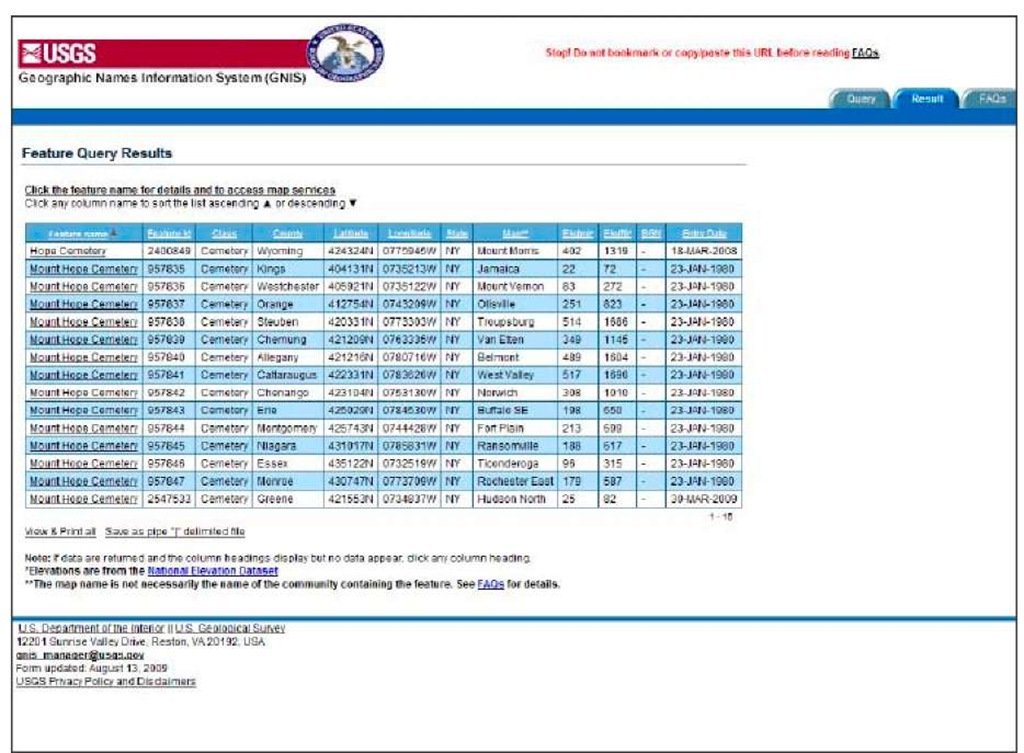

3. You can search many different ways. To search for a specific cemetery, as shown in Figure 3-3, do the following:

1. Type in the name of the cemetery.

2. To narrow it down a bit, type in the county name and choose the proper state.

3. Select Cemetery under Feature Type.

4. Click Send Query.

The site can sometimes take a painfully long time to search, but eventually it displays a list of search results, as shown in Figure 3-4.

Where is (old) home sweet home?

As I do a bit of genealogical research to find the source of my genes, I sometimes come across confusing maps showing where this or that ancestor made his home. I can’t go to the grocery store without getting lost, so you can imagine my confusion when reading these homestead maps, let alone actually traveling to an old homestead.

Wouldn’t it be easier if I knew the longitude and latitude of places I want to visit and then use my GPS receiver to find them? Why, yes, it would be easier.

Figure 3-3:

Searching for a particular cemetery

Figure 3-4:

A list of cemeteries in New York State with the name Mount Hope.

Just like finding cemeteries with Uncle Sam’s (celestial) help, you can use GPS coordinates to help locate where your relatives migrated within the United States. Why not just use a map? Like I said, I get lost on the way to the bathroom, so simply finding a location on a map, perhaps in another state, and driving there is not a reasonable expectation.

Instead, you can use the GPS navigation skills you discovered in the preceding topic to travel to locations you want to visit as part of your genealogy research. Remember, these towns may be so small that they are difficult enough to find on a map. By using your GPS receiver, especially one designed for automobile use, you can find those homesteads quicker by following the coordinates.

Don’t forget to write down and make available the locations’ coordinates to genealogists, homesteads, farms, county courthouses, and local libraries.