Just five years ago, wireless networking was expensive and difficult to set up. Fortunately advances in technology have lowered costs and increased features, resulting in something that’s both affordable and easy to set up. In fact, it’s hard to ignore wireless networking now because it’s everywhere!

Wireless networking has many benefits, including:

♦ Mobility: If you can drag your computer somewhere, you can get on your network from there. You don’t even have to shut it down! Take your computer from the kitchen to the bedroom without having to close your work or tell your chat buddy "BRB" (that’s "be right back" for those who were wondering).

♦ Fewer cables: Technically, there’s only one less cable, but I’ve found that the network and power cables are the most bothersome. Now all you have to worry about is power, and I’m sure you’ve got more power outlets than network drops in your house.

♦ Expandability: Adding a computer to a wireless network takes a few mouse clicks. Adding a computer to a wired network often takes a drill and a lot of cable. Plus, you have to make sure you’ve got enough network ports. Guess which is faster to get up and running?

This topic gets you started building your own wireless network. First, you need to determine what it is that you want to get out of your wireless network. Next, you find out how wireless networks work, and apply this to finding any potential trouble spots in your house. Finally, we get you ready to go shopping!

Figuring Out What You Want to Do

Before you even think about how to build your wireless network, take some time to figure out what you want to do with it. Hey, maybe you don’t even need wireless. Would this be a bad time to mention your bookstore’s "no refunds" policy?

When it comes down to it, networks connect people. You might connect to gain access to a service such as e-mail or the Web, or you might connect to share some files between two computers. Wired or wireless, a network’s value is in the connections it provides.

You can do pretty much anything on a wireless network that you can on a wired network. Your requirements affect the kind of equipment you need, so it’s important that you think about what you want to do before you open your wallet.

Think about which of the following you’d like to be able to do:

♦ Access the Internet. The Internet’s a big place, and to see it you have to connect your network somehow.

♦ Share files. Do you have more than one computer in your home? Do you want to be able to get files between the two? Or maybe you’re looking for a separate device to store files on, and you need to connect to that. Are these small files, large files, or huge files? Even though USB key fobs are cheap, you can’t beat the convenience of being able to copy files by the drag-and-drop method.

♦ Watch video. Services are available that let you watch video over the Internet. You may also have a device that will let you watch TV over your home network. Either way, video introduces some demands that not every piece of wireless equipment can accommodate.

♦ Play video games. If you’re a gamer, then you know how network conditions can affect your game. You can’t control much on the Internet, but you can make sure that your network’s not the problem.

♦ Print. Printers are coming with wireless capabilities now, so you can put your printer wherever you want, or move it whenever you need.

Give some thought to devices you have that may already be wireless capable. They may need an upgrade, or alter your plans slightly, depending on their age. You don’t want that old PC you got from your aunt dragging down the speed of your network if you can avoid it.

Finally, think about where in your house you want to use your computer and wireless peripherals. We get into the details about range shortly, but a wireless solution for a living room will be different for a 30-room mansion, especially if you also need Internet access down in the guest mansion. What’s that? Your guest mansion’s empty? When can I move in?

Going the Distance

Just like your favorite radio station, the radio waves from your wireless network can’t travel forever. And even if they could, your computer doesn’t have the power to talk back.

Unlike your favorite radio station, the distances involved are much smaller. A radio station’s coverage is measured in miles; your network is measured in feet.

Why, you ask? Isn’t all radio the same? Not by a long shot! A radio station’s power output is around 100,000 watts; your wireless devices are under a tenth of a watt. Frequency plays a part in it, too — higher frequencies travel shorter distances. Your wireless network’s frequencies are at least 20 times as high as your radio’s.

The wireless engineers at the IEEE are constantly updating their standards to give you faster speeds and better distance. (Incidentally, IEEE used to stand for Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, but taking a page from a famous fried chicken chain, they have rebranded themselves just as IEEE, which is pronounced "Eye-triple-E") These standards are supposed to ensure that if you buy two products from two different vendors, they can work together.

IEEE standards for wireless have a name starting with 802.11 and ending with a letter. Each letter is a different standard that may or may not be interoperable with other standards. We talk about the standards in the next topic, but just so you have an idea, here are some of the ranges of the various standards.

Table 1-1 shows ranges you can expect in a typical indoor environment. Note the use of the word typical. Depending on your hardware, your environment, and where you place your devices, you may see better or worse distances.

Table 1-1: Comparing Wireless Radio Ranges

|

Standard |

Typical Indoor Range |

|

802.11a |

100 feet |

|

802.11b |

150 feet |

|

802.11g |

150 feet |

|

802.11n (draft) |

300 feet |

It’s Wireless, Not Magic!

In the previous section, you learned that your wireless network has a limited range, and that it’s hard to place a finger on what that range will be. In this section, you find out what kind of things cause problems with wireless signals.

A simple wireless network consists of a central radio, called an access point, that connects to a wireless transmitter/receiver in your computer, game console, or portable device. The access point is responsible for everything on the wireless network, so it’s important that your equipment and the access point have no problems communicating.

Wireless isn’t magic. It’s a radio wave. Radio waves follow the laws of physics, some of which have the end result of damaging radio signals to the point where they can’t be decoded. A signal that can’t be decoded is useless to all involved; the result is a slow (or nonexistent) network.

In general, wireless problems fall into two categories: interference from other radio waves, and interference from physical objects.

Interference from other radio waves

Whatever country you’re from, your government likely regulates which wireless frequencies can be used, by issuing licenses to people for certain parts (bands) of the radio waves. The governments do this in part to make sure that multiple people don’t try to use the same frequency and step all over each other. (They also do it because they get large sums of money out of the deal.) Have you ever played with remote control cars when two people pick up a transmitter with the same frequency? Oh, what fun that is, when the single car tries to respond to two sets of commands.

Wireless network devices operate in unlicensed bands. Unlicensed bands are free for anyone to use as long as they abide by the rules the government set out. These rules, for one, limit the power output of a device so that your transmitter doesn’t interfere with your whole block.

Anything transmitting in the ranges that wireless radios use (2.4 GHz and 5 GHz) is a potential source of interference. Other wireless networking devices can cause problems. This is why the IEEE specified several channels within the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands. These channels are on slightly different frequencies so that two devices can coexist. We go over a lot more information about adjusting your channels later in this topic, but for now, remember that having two access points on the same channel is a bad thing.

Microwave ovens emit interference in the 2.4 GHz range, which as you now know is the same as what your computer’s trying to use. Playing with your access point’s channels is not going to do much here, because microwave ovens interfere with all of them.

Your best bet for dealing with microwave ovens is to get them as far away from your computer and access point as possible. For example, I’ve got my microwave oven in one corner of the house and my access point on the opposite corner on a different level. This arrangement usually works unless I’m trying to use my computer in the kitchen with the microwave on.

Another source of interference is from cordless phones. Phones generally come in 900 MHz models, and, you guessed it, 2.4 GHz. Cordless phones bounce around from frequency to frequency to try to avoid interference. You’ll probably find that the wireless network causes you more problems while talking on the phone than the other way around, though. However, if you’re having periodic network problems and can’t pin a cause on it, you might want to check and see if someone’s talking on a cordless phone at the time.

Interference from other items

Radio waves can be interrupted in flight by almost any solid object. Walls, doors, furniture, and even glass can degrade your wireless signal.

Walls are likely to be your biggest concern. In general, the bigger and thicker the wall, the worse it’s going to make the signal. Simple drywall walls may not cause a problem, but brick or stone walls, or metal (such as a concrete wall reinforced with rebar), are going to cause problems.

If your house has several levels, then try to determine what kind of material is between the floors. In a house, it’s usually wood, which is only a mild barrier to radio waves.

The easiest approach to dealing with interference is to place your access point as close as possible to the places you want to use wireless. If you find some dead areas, you can try moving your access point. In the worst case, you buy a second access point or a repeater to give service to the dead zone. It’s a lot cheaper than knocking down walls, after all.

Radio engineers have also found other problems caused by walls and furniture that have to do with the way radio waves bounce off of things. The 802.11n standard has features to deal with these.

Preparing to Shop

When wireless standards were first introduced, the cost of wireless was obscene. Access points ran in the thousands of dollars and were marketed to big companies with buckets of cash. Unsurprisingly, the technology was much slower and difficult to manage.

The technology life cycle

If you’ve followed any area of technology, you’ll know that stuff keeps on getting better. Cameras get smaller, computers get faster, and televisions get bigger. You might expect that you’d have more options and be able to choose how fast you want your computer to be, but that is rarely the case.

When making parts for electronics devices, it’s in the manufacturer’s best interest to make as few versions as possible. Over the past couple of decades, Intel has made chips for computers that run from 4 MHz to over 3 GHz. Digital cameras started out well under a megapixel but have now blown past 12 megapixels. USB memory keys started out at megabyte, and now they’re replacing your hard drive. But try to go to a store and find the full array of products? Not going to happen.

Part of it is that people are buying the higher end gear, but it’s also that it costs more to make the old stuff. Chip-making machines have already been retooled for the newest chips. The chips to make a computer’s wired network card run at the original 10 megabits per second cost a lot more than the ones that let them run 100 times faster.

At the same time, manufacturers shoot for certain price points. In the 1980s, a new computer cost around 82,000. The next model was faster and had more space, but it still cost around 82,000. Once the old model was sold out, it wasn’t being made anymore.

This 82,000 price point carried on for a while. Then the introduction of the Internet drove demand for computers up, and advances in manufacturing (and the increased demand) drove the manufacturer’s cost down. Now that 82,000 price point is much closer to 8400.

The same goes with cellular phones. The price of phones has stayed the same, but you just get more features. Phones now have cameras and built-in MP3 players and can play video games. It’s hard to find a basic cell phone now. The demand is low, and it’s getting so cheap to add the phone or MP3 player that it makes more economic sense to not offer the bare-bones version.

Every so often something disruptive comes to a product that makes the current technology less desirable. Plasma and LCD televisions made older tube televisions cheap, for a while, as manufacturers tried to get rid of their parts inventory and to make a profit off their soon-to-be obsolete technology while they could. When a new wireless standard is on the horizon, the current technology drops in price. The popularity of wireless made the price of wired network equipment take a nosedive as manufacturers tried to keep the sales coming in.

Now, competition in consumer-grade computer equipment has driven down prices, and advances in manufacturing have allowed engineers to do more with less.

Prices in consumer electronics tend to follow an interesting pattern. First, the cost is high as a new technology is introduced. As the technology gains ground, the price drops as competition enters the market. This should not be a surprise.

However, as the technology matures, the cost stays within the same range; you just tend to get something that’s smaller, faster, or more feature rich than the device that came out the month before. Instead of staying on the market, older equipment just goes away as it gets replaced. Prices fall only after something really innovative happens, usually because the manufacturers want you to stay with that technology instead of the new thing.

Within the price range of a particular technology, you find that the latest and greatest model costs the most. If you want to save a fair bit of money, you can get something with 90 percent of the features and speed of the device that happened to be new just a little while ago. You can also go really cheap and get a knock-off device made by a company you’ve never heard of. Each has their advantages and disadvantages.

All that said, the next section has a list of the types of equipment you’ll be looking at, along with the expected price range.

Putting Together Your Shopping List

Here’s where you get familiar with the types of equipment you might need and devise the list of what you need.

♦ A wireless access point connects your wireless network to your wired network. The access point’s job is to manage the wireless network and relay messages between the wireless and wired devices. An access point costs between $50 and $150, depending on the technology.

♦ A wireless router is really a few devices in one box. It’s a firewall that connects your network to the Internet and provides some network services and safety along the way. We go over these features later. The router also has a built-in access point. Optionally, the router can have a few wired network ports.

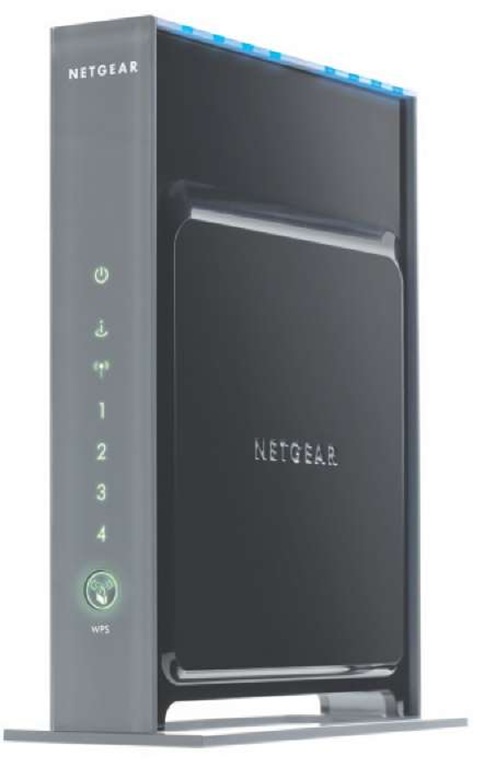

Wireless routers, like the one in Figure 1-1, go for $50 and up, depending on what extra features are on them and how fast they go. Most quality routers are in the $100 range, though. A wireless router can also be used only as an access point by plugging it in a certain way and not configuring all the features.

♦ A wireless range extender (shown in Figure 1-2) is used to boost a wireless signal for areas where the signal is weak. These, too, are like access points (some can double as an access point). As long as the extender can receive the signal well, it can rebroadcast at a higher power to extend the range. You should be able to find range extenders for $50-$100.

Figure 1-1: A wireless router.

Figure 1-2: A wireless range extender.

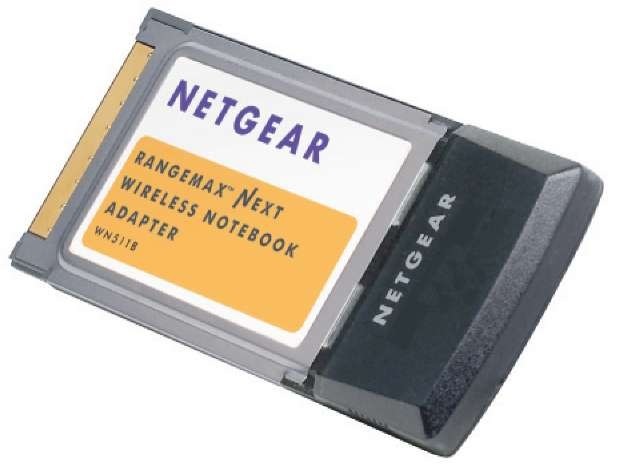

♦ On the computer side of things is the wireless NIC. For laptops that don’t have wireless built in, you need a notebook adapter, sometimes called a PC card for your computer. These devices cost from $50 to $150, depending on features and the standards the card supports. Figure 1-3 shows such an adapter.

Figure 1-3:

PC card adapter.

♦ If you are upgrading a desktop machine, you have a couple of options. You may buy either a PCI card that goes inside the computer or a USB-based one that plugs into a free USB slot. Note in Figure 1-4 that the PCI-based card has an external antenna, which is helpful in obtaining the best signal, especially if your desktop is in a tight spot.

Figure 1-4:

PCI wireless adapter with external antenna.

Nothing says you can’t use a USB adapter with a laptop. You’ll find the PC card is probably more convenient because part of the card is inside your computer.

Wireless cards for PCs cost about the same as their laptop counterparts, though you may pay slightly more for the benefits of an external antenna.

To get your shopping list started, you’ll want an access point or a router, plus a wireless card for each device you want to get on the network. Take stock of your existing computers; they may already have a wireless NIC built in.

Don’t pull out your wallet just yet. We’ve yet to get into the various options you have underneath the wireless umbrella. There are different radio standards, frequencies, antennas, and routers . . . I’m getting excited just thinking about the possibilities!