abstract

Because most medical school textbooks do not adequately address pain management, the American Academy of Pain Medicine wanted to create TOP MED, an online textbook that would address this need for different specialties and which also could be used as a textbook for the Introduction to Pain Management course. This online textbook would cover 11 topics and consist of the latest findings from the most renowned experts in the different disciplines of pain medicine. This case study is a description of the process of designing and producing the online textbook.

introduction

The American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) is the medical specialty society representing physicians practicing in the field of pain medicine. Because most medical school textbooks do not adequately address pain management, the academy wanted to create TOP MED, an online textbook that would address this need for different specialties and which also could be used as a textbook for the Introduction to Pain Management course. This online textbook would cover 11 topics and consist of the latest findings from the most renowned experts in the different disciplines of pain medicine.

This case study is a description of the process of designing and producing the online textbook, including how we determined what to cover and how we involved the subject matter experts and translated their content into interactive, entertaining learning segments.

E-LEARNING PROGRAM

The academy had created reference materials online, and they published articles, but this was their first program that was designed for teaching medical professionals. One requirement was that the program have similar production values to television; they did not want something that looked like PowerPoint slides; they did not want talking heads; and they did not want just video. SmartPros, Inc. developed TOP MED for the American Academy of Pain Medicine. The author served as the instructional designer and overall project manager.

academic and administrative issues

The academy wanted TOP MED to be an online textbook, not an online class. The typical use would be, say, in a course on pediatrics. When the professor wanted to cover pediatric pain, the students would turn to TOP MED to find out the different ways the children felt pain, how to assess pain in children, how children react differently to drugs, and how pain affects children’s, and their family’s, lives.

The academy also wanted there to be an assessment at the end of each section so that the professor and the students could determine knowledge acquisition.

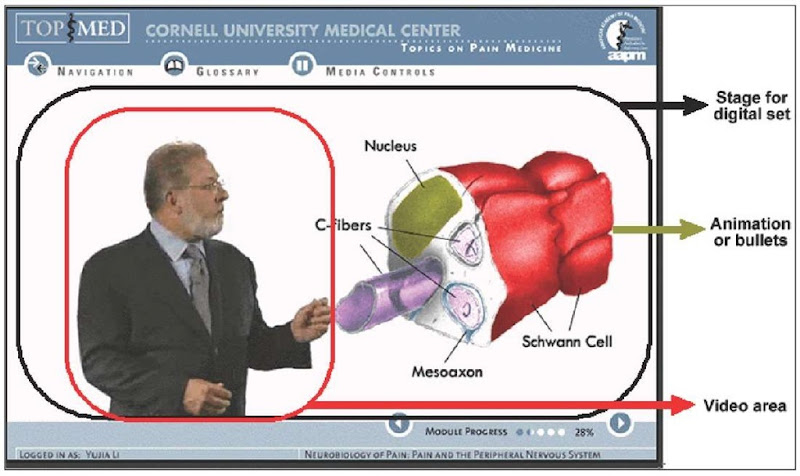

The use of video created an interesting problem. The client wanted the course to look as if the video was full screen, but bandwidth considerations prevented the use of full-screen video. One solution could have been to find or build a proprietary solution to serve and access the video. Another could have downloaded the video onto student machines during off-hours. We wanted a more standardized and immediate solution, so we took advantage of a feature in Flash that allowed us to blend video into a Flash animation. We built a virtual “set,” which blended in with the video to give the appearance of full screen video without the huge bandwidth requirements.

As a textbook for medical school students, TOP MED has to be authoritative, drawing scientific content from experts. We needed people at the top of their field, individuals who were either conducting or utilizing the latest research. Then we needed to distill and transform their knowledge into lessons for individuals who might become general practitioners, not necessarily pain specialists or researchers.

But if we just wanted to present content, we could have produced a book, audiotape, or video. We wanted to benefit from the unique advantages of a Web-based instructional system, using high quality video, student interaction, assessment and feedback, flexible navigation, tracking, and reporting.

The client wanted the actual lessons to primarily be delivered via video, but they were adamant that the content not be delivered as talking heads with bullet points. They wanted the material to look like full screen video. This is problematic over Internet protocols, because, to be of reasonable production quality, video requires significant bandwidth. We were able to solve this problem by using video embedded in Flash animations. By blending the video in with a digital set, we minimized the size of the video, but the set looked like the video was full screen.

We decided on 12 units, which could later be expanded:

|

1. |

Introduction |

|

2. |

Neurobiology of pain |

|

3. |

Neuropathic pain |

|

4. |

Analgesics: NSAIDs and COXIBs |

|

5. |

Analgesics: Opioids and Adjuvants |

|

6. |

Patient evaluation |

|

7. |

Acute and postoperative pain |

|

8. |

Musculoskeletal pain |

|

9. |

Cancer pain and palliative care |

|

10. |

Pediatric pain |

|

11. |

Misuse and abuse of pain medications |

|

12. |

Race, culture, and ethnicity in pain management |

The rationale for sequencing the modules was that we would begin with an introduction to TOP MED and a review of how pain is perceived in the medical community and the population as a whole. The next two units are on how the body reacts to pain and painful stimuli. The two units on analgesics focus on the common medical treatments for pain. Evaluation is necessary for any manifestation of pain. Then the next series of units focus on different common causes and the corresponding treatment for pain. The last two units focus on particular aspects of pain management, which go across all types of pain symptoms and treatments. We started by designing and producing two units: neurobiology of pain and pediatric pain.

Our original goal was that each module should last about a half hour. This was based on initial guidance from the advisory board. We planned the following sections for each module:

1. Introduction: what this topic includes and why it is important.

2. Series of four to eight lessons, each consisting of:

2.1. Introduction to the lesson

2.2. Video lecture with animated, text, and graphic aids

2.3. Summary

2.4. One to three questions, problems, or exercises

2.5. Possible links to supplementary material

3. Conclusion of the topic

3.1. Animated summary of the whole topic with voice

3.2. Quiz of 10 to 20 questions

3.2.1. Each question will have an explanation of how the correct question was arrived at and what learning material was represented

3.2.2. Student responses will be tracked

4. Extra materials

4.1. Printable files of all textual and graphical content

4.2. Glossary with definitions of key terms

4.3. Index of all key topics

Subsequently we decided that the end of module quiz would have a question bank of 30 questions, and that students would get a random sampling of 10 questions each time one took a quiz. Additionally, we combined the index and glossary into a searchable glindex that both defines key terms and links to content in the modules.

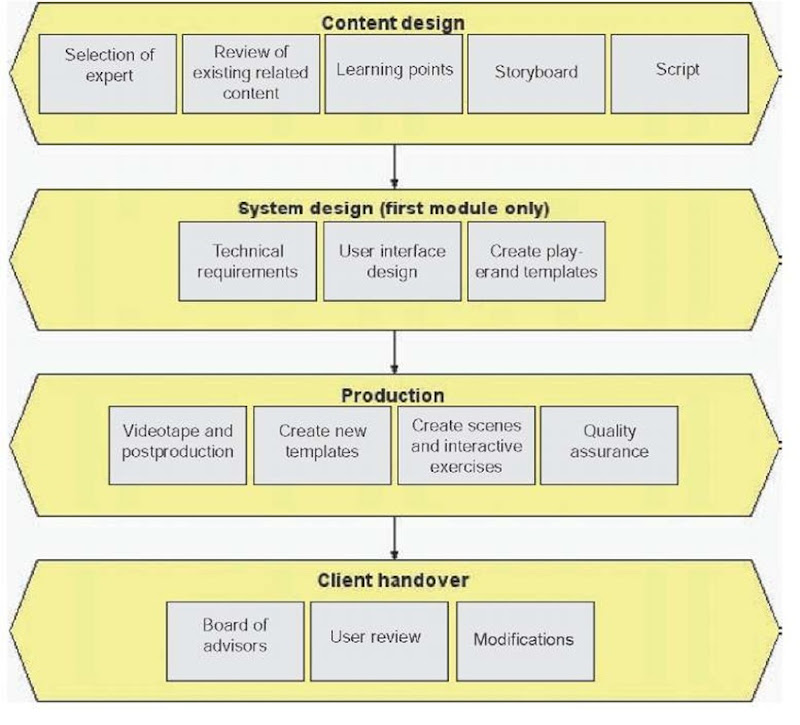

Figure 1. Phases in TOP MED development

Our project plan divided our work into four phases. For all modules, there would be a content design phase, a production phase, and a client handover phase. On the first module, we would also perform a system design phase, which would include prototypes that used material from the first module. Figure 1 shows the steps in each phase. The balance of this article will detail how each phase was carried out.

content design

selection of Expert

For this project, the experts were chosen by the client, generally some of the best-known people in the field of pain medicine. In addition to the expert, there was an overall medical editor, who chaired the group that wrote the original federal guidelines on the treatment of pain.

Review of Existing Related content

AAPM was able to provide videotapes of many of the experts teaching these topics, or at least lecture notes. These videos were generally from 45 minutes to 90 minutes long. The experts also provided copies of materials that they used when they lectured.

Very few of the materials had the production values we needed. There were minimal graphs, grainy unlabeled photographs, and, with one exception, rudimentary animations. But often the content was extremely relevant leading us to conclude that we would have graphic artists recreate and animate graphics and charts.

Learning Points

This phase of development produced an interim and then a final learning points document. The interim document contained a series of learning points with questions for the medical expert, while the final document was used to produce the storyboard.

The instructional designer (ID) first transcribed any video lectures and then outlined the concepts that were covered. There were two key tests for content: (a) would a doctor knowing this information do a better job with a patient (relevance), and (b) if a person did not already know the information, was the way it was presented sufficiently clear to learn from (clarity).

In terms of relevance, if the ID was certain that the information would not help a general practitioner, it was not used. If it was clear from the materials how it was helpful for a doctor, it was included. If there was a question, the information was tagged so that it could be reviewed with the expert. Sometimes the instructional designer could research the topic.

For example, there were concepts that were backed up with intricate descriptions of scientific research. While the concept itself was useful, and the research would have been necessary for people going into pain research, the detailed research explanations were excised from the learning point document, pending approval from one of the content experts.

In terms of clarity, if the explanation was sufficient, it was copied into the learning points. If it was not clear, the subject was researched and/or tagged for discussion with the expert. For example, the following point from the neurobiology of pain module is important to the material and would be understood by those who were already familiar with the topic. But we deemed it too erudite for an introduction to pain management textbook:

There is NMDA receptor-mediated central sensitization that amplifies the input coming both from the injured tissue and also the unharmed tissue surrounding the area of injury.

This statement would be tagged for a more expansive explanation. So that you can see the contrast, refer to Example A for this explanation as it appears in the final script.

And while this text would never make it into a Stephen King best seller, it is something that a second year medical student should be able to understand.

Finally, items were grouped into general topics or sections; all technical terms were defined in footnotes; and a request was made for clinical examples.

The interim learning points document thus had:

• A list of topics that had been covered in lectures or in any additional research.

• Points tagged with, “how is this useful to a doctor?” Or, “why should someone learn this?”

• Other points tagged with, ” how else can this be explained?”

• Terms that were tagged with definitions were questioned as, “is an explicit definition necessary in the lecture, or can it just be defined in the glossary?”

• For each topic or section, there was a question, “can you provide a patient history that will illustrate some of the points in this section?”

Once the interim learning points document was assembled, the ID met with the expert face to face. This meeting tended to take about four hours to review all of the questions.

Armed with the answers to the questions and the case studies, the ID would then assemble the final learning point document and submit it to the expert for review. Generally, a one-hour phone meeting was sufficient to review and approve this document.

It also became evident very early on that, for the topics contained in the TOP MED course, modules were going to be 45 to 60 minutes long, not 30 minutes. The learning point documents (Figure 2) tended to run about 20 pages of 12-point font.

Example A.

How does central sensitization occur?

Glutamate appears to play a key role. Glutamate is an amino acid released in excitatory synapses. It affects several types of receptors, both in the spinal cord and in the brain. One of these receptors can be labeled with an artificial reagent, N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA). That receptor is therefore termed the NMDA receptor.

The NMDA receptor has binding sites for the neurotransmitter glutamate and several other substances that modulate its activity, including glycine, zinc, and various polyamines.

We know that two things have to happen for activation of the NMDA receptor in the spinal cord.

First is the firing of the nociceptor, which causes depolarization and ion flux across its cell membrane, which in turn causes the release of glutamate into the synapse. Prolonged firing by C-fiber nociceptors causes release of glutamate.

Second is the binding of glstamate to the bostsynabtio NMDA receptor—keeping in mind that other chemicals also bind and may have additional roles.

Activation of NMDA receptors causes the spinal cord neuron to become more responsive or sensitive to all of its inputs.

Figure 2. Sample learning points page

Causes and implications of cancer pain

“NeurologyH

Pain is nociceptive, neuropathic, or both; many cancer patients have a mixture of bothfi Nociceptive^

Bone invasion by tumor can be one of the most severe pains associated with metastatic disease.If

Infiltration and occlusion of blood vessels can cause ischemia2 and pain, after which neuropathic pain may be persistent. If

Obstruction of a hollow viscous can lead to visceral pain syndromes, which can be quite severe If

Swelling of a structure invested by fascia or periosteum can be very painful.If Necrosis and/or infection of cancerous tissues, with inflammation and ulceration, are tumor-specific pain.If

Post-chemotherapy and radiation therapy syndromes are very common, even when a patient is in remission or has been cured. If Any persistent pain syndrome can lead to sensitization and so-called “wind up” of the central nervous, leading to a chronic neuropathic pain state (see TOP MED module on Neurobiology)^

Neuropathiclf

Compression or infiltration of nerves, nerve roots or spinal cord is a potent stimulus for acute or persistent neuropathic painlf Concomitant neurological disease, eg., diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgialf

Post-surgical, chemotherapy and radiation therapy neuropathieslf

storyboard

We decided based on the length of the material that we needed to have more than one presenter for each module. We fixed on an intro/review person, an explanatory person, and the medical expert. We also learned that we generally needed to change speakers every minute or so, although a few segments, as long as three minutes, could still maintain interest.

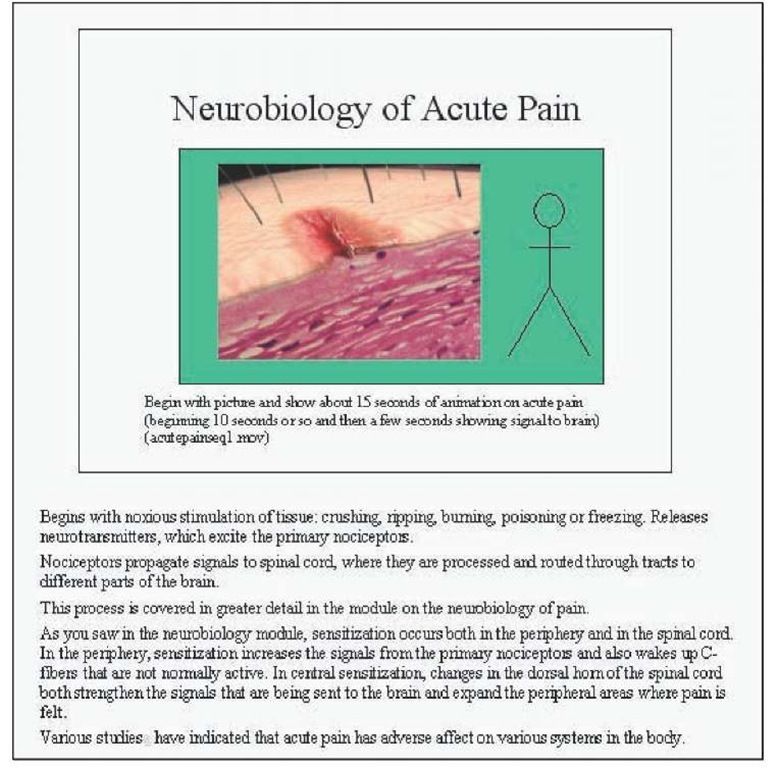

The storyboard document was produced in PowerPoint. The slide showed a stick figure of the actor along with any bullet points or graphics that were going to be displayed, and the speaker notes contained a copy of the learning points that were going to be covered in that scene. If a learning point could be diagrammed, then there would sometimes be a full screen animation along with a voice-over instead of a video.

If there was going to be a graphic, chart, or animation, the ID would create a “wire-frame” from which a graphic artist could work. At the end of each section there were general instructions for an interactive exercise to be completed by the student, generally some type of drag and drop problem. The storyboard was then reviewed with the medical editor. This was also generally a three-hour meeting. The medical editor would typically point out places where the medical expert needed to make his/her sources more explicit, needed more updated references, or, in a few cases, where recent data had modified the assertions.

The comments and storyboard were then reviewed by the medical expert and passed back to the ID. The ID created a final storyboard (Figure 3), which was then reviewed one more time by the editor and medical expert.

script

The scriptwriting is in three stages. A scriptwriter writes the script. It goes through a review process with the medical editor and instructional designer. Blocking and animation instructions are added. For this project, we used a scriptwriter who had written video scripts for pharmaceutical companies. He provided a fresh perspective to the material. The scriptwriter also wrote any bullets that would appear on the screen and completed the end of section exercises. We determined that there should be some bullet or some change to the screen every 5 to 10 seconds in order to maintain interest.

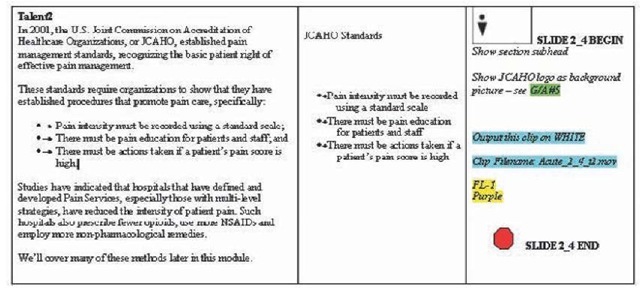

Figure 3. Sample of story board page

Figure 4. Script sample

The script (Figure 4) was then reviewed by the instructional designer and then the medical editor, and then the production team added animation, bullet, and stage instructions.

system design

Technical Requirements

There were three broad areas that needed to be defined for TOP MED: (1) the player that would be able to display something that looked like nearly full screen video over the Internet; (2) the features of the learning management system (LMS) that would be used for student registration, tracking, and reporting; and (3) the hosting to meet response time and security requirements.

We knew that we would not be able to send a 600×800 pixel, 15 frames per second video over the Internet. It would be too large, requiring too much bandwidth on both the hosting and the user side. On the other hand, we knew that the end product needed a high production value; students and professors would want something comparable to what they see on television. We also knew that the target audience would have access to highspeed Web access, using advanced desktop and laptop computers.

Our conclusion was to use Flash Video. We would tape all segments on a chroma-key background and then blend the video image into the rest of the Flash stage in order to give the appearance of full screen video, cutting the bandwidth requirements by over 75%. Of course, it sounds simpler than it is; but the SmartPros Interactive staff was able to work out all the glitches and make the process relatively straightforward.

The lesson player also needed to be SCORM compliant so that the lessons could be easily ported to different LMSs. We also knew we were going to work with the SmartPros LMS: the Professional Education Center (PEC). The LMS gave us the capabilities to interface with the Flash player, register students, track student progress, provide end of module quizzes, and create custom reports for medical schools and for the AAPM. We needed to define the specific information that needed to be sent back and forth between the LMS and the player and also to specify the key data that the AAPM wanted to maintain.

Hosting presented an interesting conundrum. Between the U.S. and Canada there are over 140 medical schools. What if all the medical schools were using the program and 16,000 medical students needed to access lessons or answer questions at the same time? What would we need for hosting? On the other hand, since we would be starting off with just a few schools for the first semester, why should the client pay for excess capacity that they were not using? On the other hand, the number of students could change rapidly, in as little as a few weeks and with little advance notice.

For us, one of the strong attractions to the SmartPros PEC was that it was already serving hundreds of thousands of users, with bandwidth, processing, and storage to accommodate spikes in demand. If we started with just a few schools and the numbers of students increased by a factor of five three months in a row, it would not be a significant jump in the demands faced by the overall system.

User Interface Design

The user interface design involved both the LMS and the lesson player. For each, we first defined the types of operations a student was likely to perform. From the LMS, a student would need to register, logon, go to a specific module, take a test for a specific module, view results from previous tests, and view descriptions of the different modules. The priority for the LMS was to make these as easy as possible and keep the screen as simple as possible.

A student would be looking at a particular module from the player. From within that module, a student would want to continue, go to a particular section, fast forward or backward, pause, turn off the sound, take a quiz, see results for the previous quiz, look up a word, find where a topic is covered, and go back to the LMS.

We wanted to make these tasks simple; we wanted a unified color scheme and slide layout, but with a few different options to maintain interest. We initially brainstormed the different ways that the features could work and how they would relate to each other. A graphic designer then created screen layouts for five different looks, which were discussed with the client and sample users. Once we had narrowed the look down to two, we created working prototypes using the materials from the first module. These were again discussed with the same groups, and we ended up with our final look and feel.

Player and Template creation

In order to allow for multiple developers to work on the material, we created the Flash player. All navigation and media controls were built into this player. Inside the player, there was a stage area. The player was designed to run each scene on that stage. The scene developer thus only had to worry about the specific content that was going to be deployed in that scene.

We then created different digital set templates for the different types of scenes: Introduction, Summary, Activity, person on left, person on right. The scene developer would receive a flash video file (flv file), a list of animation elements and/or bullets, and background photographs. The job of the developer was to assemble these source materials and choreograph them with the video. Figure 5 is a sample of the player with a digital set running.

production

Videotape and Post Production

Videotaping was performed in a green room with a teleprompter on the main video camera. Before each scene the actor would be coached on how to enter the frame, when to gesture, and where to stand.

With the medical experts, our challenge was to get them to relax and move freely in front of the camera. With the actors, it was pronunciation of medical terms like parenterally, NSAID, and allodynia. We found that one-hour of video required about one and one half days of shooting. The good takes were then transferred to flash video files and the sound was normalized.

create New Templates

As we progressed with additional modules, we found we periodically needed to add to the number of templates, for example, person starting on left moving to right, person starting on right moving to left, and voice over with animation were all added to the original templates.

Figure 5. Sample player view

create New scenes and Exercises

We created a styles document and sample scenes that were given to the developers along with the templates and objects that were relevant to them. Before development started we had a kickoff meeting to discuss the purpose and audience of TOP MED, the story for that particular module, the graphics, bullets, and animations for each scene, and how to use the style document and templates.

Quality Assurance

There were two initial rounds of quality assurance for each module, with four individuals going through each scene. For the third round, the medical editor and two representatives of AAPM also participated in the review. The status of all suggestions and findings was maintained in a database that was accessible to all of the QA staff. The project manager was responsible for discussing each finding with the QA individual(s) who found it, verifying it, and then ensuring that the developer understood the changes.

client handover

Board of Advisors Review

In February 2005, the board of directors of the American Academy of Pain Medicine viewed the first two modules, and the result was very well received. In fact, one of the directors mentioned that this would be a good prototype for the way medical textbooks should be produced. The general comments were that the length of the modules was appropriate, the content was current, relevant, and focused, and the presentation would maintain the interest of the target student.

User Review

There have been quite a few doctors, residents, and students who have viewed the material. More formal review with medical school classes is also planned.

Modifications

There were three main changes that were requested from our initial feedback. First, since the first impression is going to be from the introduction to each module, we needed to make the intro compelling, and we have added graphics and animations to the background of these sections.

Second, while we initially felt the washed out colors would reduce learner fatigue, the feedback was that we needed a brighter color scheme. We have increased the color contrast for the second and third modules. Third, the initial feedback on the second module was that we needed to add a few animations, which we have done. We also increased our use of animations in the second two modules.

Program Evaluation

A panel of medical experts evaluated all contents for accuracy, currency, and relevance before the program was created. Since the first modules were created, the program has not yet been fully evaluated. We have shown the program to doctors, nurses, and med school students. The feedback has been very positive, but we do have a punch list of changes, most of which are minor. Currently the academy is waiting for the next level of funding to conduct a full evaluation and complete the additional modules.

Networking and collaboration

TOP MED was designed to be run asynchronously; there is no collaboration built into the program itself. Instead, it is designed as a tool to be used by a professor to provide content to students, with projects to be assigned by the professor as part of the class.

Policy implications

The advisory board of the AAPM has indicated that they would like to provide more materials in this fashion and that the cost for creating this course was similar to the cost of developing a textbook with similar content. They feel that this style more closely addresses how the current generation of doctors will want to study.

sustainability and conclusion

TOP MED was designed in such a way that additional modules could be added. Because of the use of video, though, it will be difficult to edit existing modules should methods become obsolete; it is difficult to splice in a new video and have it look continuous.

By having the project sponsored, the AAPM is ensuring that there are no monetary hurdles for students to obtain the content. On the other hand, TOP MED is dependent on the ability of the AAPM to find partners who can afford the approximately $75,000 it takes to create each one-hour module.

Lessons Learned and Best Practices

We thought that the process of defining the content, developing scripts, building in interactivity, and then taping, developing, and editing worked very well. After watching the first two modules, we learned how to make additional transitions to keep the students’ attention and the importance of frequent reviews, especially reviews that explain the content in a different manner that when it is first explained.

The three actions that can be identified as best practices are:

1. Determine the needs and content that is needed before doing any of the work. This means pulling the content from a variety of sources and having it checked by content experts.

2. Develop a script with stage and animation instructions before any videotaping or animation development. It is very valuable to have these instructions reviewed by people experienced in animation and video to make sure that what you have envisioned will maintain the interest of the audience and to see if there are alternatives that might be lower cost but just as effective.

3. Flash was a great tool to work with, but you do need experts in Flash, and you need to build in four to five quality assurance rounds. You need to test to see if the product functions and also if it works for the intended audience.