Introduction

Witnesses are often critical for investigations and trial evidence, simply because other forensic evidence is missing. However, people are not cameras. They cannot be treated, or considered, as physical evidence. The true value of the eyewitness is much more fragile, and we must handle his or her testimony with special care. One respected source estimates that 56% of false incriminations have been due to eyewitness error.

When witnesses personally know the culprit, facial identification methods are of course not needed. The witness simply reports that ‘John did it’. Identification issues arise when the culprit is a stranger. The problem is then far more difficult, because the witness has usually seen the culprit for only a short time. Memory of the face is imperfect.

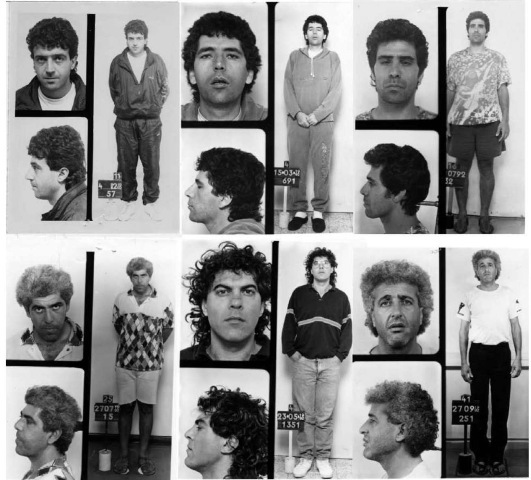

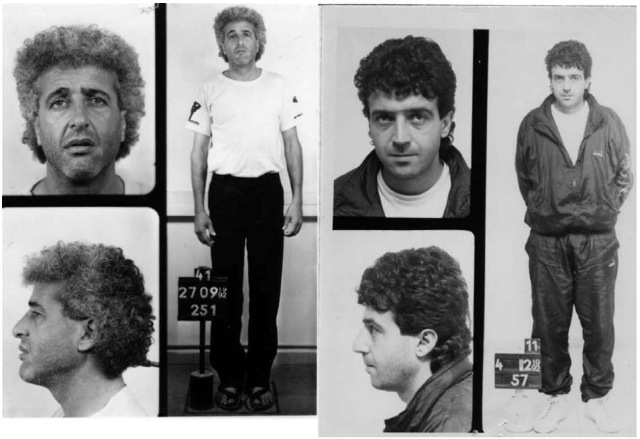

The police, who deal with facial identification, have three tools with which to utilize eyewitnesses. If they have a suspect, they conduct a line-up (Fig. 1 ). If they do not, they conduct a mugshot search (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 Six-person photographic line-up. The suspect is in the middle of the top row.

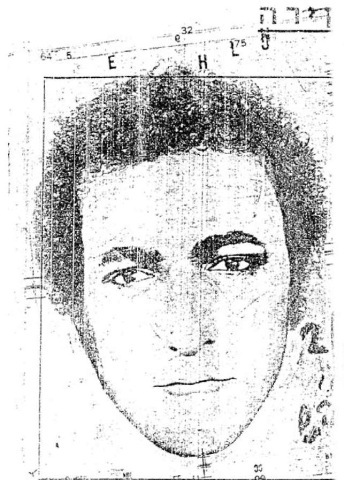

If that fails, they can fall back on the composite (Fig. 3).

The traditional police line-up has the witness view five to eight people, or up to 12 photographs, one of whom is the suspect. If the witness ‘identifies’ the suspect as the culprit, the suspect will usually be charged for the crime and convicted. The court requires no other evidence. If the witness chooses someone else, a foil, the police will usually release the suspect.

The mugshot search has the witness view photographs of suspected criminals, usually of people convicted for offenses. If the witness ‘identifies’ someone, that person becomes a suspect. In contrast to the lineup, however, that person does not necessarily become a defendant. The criminal justice system understands that witnesses sometimes mistakenly identify someone. In the line-up, such error will usually involve choice of a foil, a known innocent. The innocent suspect is thus protected somewhat from such mistakes. On the other hand, there are no known innocents among the mugshots. Anyone chosen becomes a suspect, and therefore there is no protection against mistaken identifications. The mugshot search is sometimes confused with the line-up. Police often fail to distinguish the two, presenting as evidence of identification a choice in an ‘all suspect line-up’ (a mugshot search). Courts often fail to note the difference.

The mugshot search, however, is still important. It sometimes provides a suspect, an essential ingredient for continued investigation. Once a witness has identified a suspect in this way, however, conducting a line-up is considered inappropriate. The witness may choose the suspect based on his or her memory of the mugshot, rather than the culprit at the scene of the crime.

Figure 2 Two mugshots.

This is just one example of the fragility of eyewitness evidence. People are better in noting that a person or photograph is familiar than they are at remembering the circumstances in which they saw that person. There have been cases in which a witness has identified a person as the culprit (he or she looked familiar), but had actually seen the person in a perfectly respectable setting.

Since mental images of the culprit may be quite vague, witnesses can be susceptible to subtle and even unintended influence by police officers who have a hunch regarding the identity of the culprit. Good practice calls for the maximum safeguards, including having the identification procedure conducted by an officer who is not otherwise involved in the investigation.

The composite is the tool of last resort. A trained police officer may create a picture of the culprit’s face with the help of the witness. Usually the police use a collection of examples of each facial feature (hair, nose, eyes etc.). Computer programs that add additional aids, such as being able to modify each feature, are being used frequently.

In contrast to the mugshot search ‘identification’, the composite is but a first step in finding a suspect. The composite is not a photograph, only a likeness -at best. A suspect is found only when some informant ‘recognizes’ the composite as a particular person.

The composite is no less immune than the other two methods from being a source of undue influence on the witness. Research has demonstrated that the constructer of the composite can influence the composite produced. The image of this composite can then interfere with the ability of the witness successfully to identify the culprit.

We will discuss the strengths and weaknesses of these identification tools, and explore potential improvements.

The Line-up

The line-up, being the major means of facial identification in court, is the chief source of false incriminations. This is caused by a serious gap between its actual and believed probative value. ‘Identification’ means ‘establishing absolute sameness,’ but in fact all witnesses do is choose a line-up member. Their mental image of the culprit cannot be perfectly identical even with a guilty suspect. Even if the mind were a camera, the culprit would have a different facial expression, be wearing different clothes, and so on. Witnesses compare line-up members with their mental image, and decide to choose when the similarity is great enough for them.

Figure 3 Composite of one member of the photographic lineup (Fig. 1).

They need not choose anyone. Good police practice reminds them of this at the outset. However, in experiments when the suspect is innocent, witnesses choose someone 60% of the time. They are simply choosing the line-up member who is most similar to their mental image. An innocent suspect has as much a chance as any other line-up member as being the most similar, and therefore to be chosen. The probability of choosing the suspect is therefore 1/n, where n is the number of line-up members. When n = 6, the innocent suspect will be chosen 60/6 = 10% of the time.

Witnesses are usually confident in their ‘identification’, and the criminal justice system overbelieves confident witnesses. Thus, courts will usually try and convict these innocent suspects. Moreover, the percentage of innocent defendants who have been chosen in a line-up is far greater than 10%. We must also consider how often witnesses choose guilty suspects in a line-up, as only they will usually be tried. In experiments, only 44% of guilty suspects are chosen, and eyewitness conditions in the real world are far worse than experimental conditions.

For example, experiments have shown that witnesses are less likely to identify the culprit if a weapon was visible during the crime, and if the witness was the victim rather than a bystander. The underlying factor seems to be distraction from attending to the culprit’s face. When a weapon is present witnesses focus on it, and when they are the victim they are preoccupied with their fear and/or how to escape. Yet, only 8% of experimental conditions have the culprit wield a visible weapon, compared to 44% of real cases. The witness was the victim in only 4% of the experimental conditions, compared to 60% of real life. Furthermore, real-world distraction is much greater: the gun is pointed at the witness/victim, who is generally assaulted physically. Thus, an estimate of 30% identifications of the guilty in real cases may be too high.

Bayesian analysis shows that under these conditions (10% innocent defendants, 30% guilty ones), 25% of the defendants are innocent. This is true if, without the line-up, there is a 50:50 chance of the defendant being guilty. Even when, without the lineup, the prosecution has evidence leading to an 0.85 probability of guilt (a strong case indeed, without other forensic evidence), then 5.5% of defendants are innocent. Guilty beyond reasonable doubt? A scientist would hesitate to publish a finding with a probability of 0.055 of being wrong. Yet defendants are often sent to jail based on weaker evidence.

This analysis is based on the assumption of a perfectly fair line-up. Unfortunately, line-ups are sometimes not fair. Informing witnesses that they need not choose someone is not universal. Without that instruction, more than 60% of witnesses will choose, increasing the rate of mistaken identifications.

Furthermore, a line-up is only fair if the suspect does not stand out in any way, and if each member is similar enough to the suspect. Chances of choosing a suspect increase if he is the only unshaven member, for example, or if the culprit has black hair but some line-up members are blonde. If, for example, two foils in a six-person line-up have the wrong hair color, the actual size of the line-up for the witness is only four members. The witness can immediately discount those two foils. In addition, the witness of course must be given no hint, by design or unintentionally, as to who the suspect is.

The officers investigating the case, the same ones who have determined who the suspect is, often conduct the line-up. Their belief in the suspect’s culpability sometimes leads them to ‘help’ the witness.

Sometimes officers have honest intentions but err. They may have great difficulty rounding up enough appropriate foils. They may put more than one suspect in the same line-up, which also increases the likelihood of choosing an innocent suspect. More and more, photographic line-ups are replacing live lineups, to cope with increasing logistical difficulties in recruiting foils. Yet photographs reduce the chances of identifying guilty suspects, and thus also increase the percentage of innocent defendants.

Even such a seemingly simple idea as choosing lineup members similar ‘enough’ to the suspect is controversial. It has been argued cogently that no logical means exists for determining how much is ‘enough’. Too much similarity (twins as an extreme example) could make the task too difficult, again decreasing identifications of guilty suspects.

The alternative suggested is to choose foils who fit the verbal description the witness gave of the culprit. Since these descriptions tend to be rather vague, lineup members would not be too similar, but similar enough to prevent the witness from discounting foils too easily (as in the case of a blonde foil with a black-haired suspect).

A number of solutions have been suggested to decrease the danger of the line-up. The English Devlin Report recommended that no one be convicted on the basis of line-up identification alone. This suggestion has since been honored in the breach. In addition, we have noted that Bayesian analysis indicates that quite strong additional evidence is required for conviction beyond reasonable doubt. Courts often accept quite weak additional circumstantial evidence to convict.

The police can prevent the worst abuses of the lineup; for example, in addition to proper instructions to the witness, an officer not involved in the case should conduct the line-up. However, we have noted that even perfectly fair line-ups are quite dangerous.

Psychologists can testify in court as expert witnesses. The goal is not simply to decrease belief in the line-up; that would increase the number of culprits set free. Rather, the goal is to provide information that could help the court differentiate between the reliable and the unreliable witness. Experimental evidence has yet to consistently support this proposal. The issue may well reside in the quality of the testimony, a question not yet fully researched.

The police can modify line-up procedure to decrease the danger of choosing innocent suspects without impairing culprit identification. The most prominent has been the sequential line-up. In the simultaneous line-up, the witness views all the line-up members at the same time. In the sequential lineup, witnesses view them one at a time, deciding after each one whether he or she is the culprit.

In the simultaneous line-up, witnesses who decide to choose when the culprit is absent do so by choosing the person who seems most similar to the culprit. That person is too often the innocent suspect. In the sequential line-up, they cannot compare between line-up members, and therefore cannot follow this strategy. The result is far fewer mistaken identifications, with very little reduction in culprit identifications.

The major problem is that people believe that the sequential line-up, actually far safer, is actually more dangerous. Despite the fact that the first paper demonstrating its superiority was published in 1985, it is widely used today only in the Canadian province of Ontario. Also, if only one line-up member can be chosen, some culprits escape prosecution. The witness may choose a foil before he sees the culprit.

A recently tested modified sequential line-up reduces mistaken identifications still more. This line-up has so far up to about 40 members, which naturally decreases the chances of the innocent suspect being chosen. Perhaps the line-up could be larger without reducing the chances of choosing the culprit.

In addition, witnesses may choose more than one line-up member; this further protects innocent suspects, as witnesses do so often when the culprit is absent. Even when the suspect is chosen and prosecuted, the court will realize that the ‘identification’ is a lot weaker, and will demand far stronger additional evidence.

Finally, the culprit has less chance of escaping identification: if witnesses choose a foil first, they can still choose the culprit later. Witnesses in experiments sometimes first choose the culprit, and then a foil. The culprit will also get extra protection in court, but that is only fair. The witness failed to differentiate a foil from the defendant, and the court should be aware of this important fact. The method has yet to be tested in the courts, but is in the process of being introduced in Israel.

Such a large line-up cannot be live. Rather than use photographs, the method relies on videoclips of lineup members. Some experiments have shown that video is as good as live. Video technology thus has the potential of reversing the trend towards photo line-ups, as videoclips can be saved and used repeatedly (in common with photographs).

The improvements discussed so far are aimed mainly at reducing the rate of false identifications, rather than increasing the rate of correct ones. The police have no control over eyewitness conditions that cause failures to identify the culprit. The police can modify the line-up method that causes the false identifications.

Yet there are still line-up modifications that may increase culprit identification. We have noted the use of video line-ups instead of photographs. The principle is to maintain the maximum similarity between eyewitness conditions and the line-up. Another obvious extension would be to add the line-up member’s voice to the videoclip. One experiment added the voice to still photographs and found marked improvement. However, distinctive accents could then act like different hair color in the line-up and would have to be avoided.

Another extension would be to conduct the line-up at the scene of the crime. Aside from creating practical difficulties, the experimental evidence is not supportive. An easier alternative would be to have the witness imagine the scene. The experimental evidence is inconclusive.

The Mugshot Search

The problem with the mugshot search today is that it is like a search for a needle in a haystack. When the method was first introduced, cities were smaller and so were mugshot albums. Today, mugshot albums are so large that witnesses can no longer peruse all the photographs and stay awake.

The essential requirement, then, is to select from the whole album a far smaller subset. The danger, however, is in throwing out the baby with the bath water. If the culprit is not in the subset, the exercise becomes futile. The challenge is to choose the smallest possible subset that includes the culprit.

The common police practice today is to use witnesses’ verbal descriptions of the culprit to create such a subset. Thus, the police categorize each photograph in terms of such features as age, hair color and body build. The witness then views only those photographs that fit the description of the culprit, indeed a much smaller subset of photographs.

The method is not without its problems. Most of the features are facial, and some research has shown that witnesses forget these quickly. Also, there is much room for error. People do not necessarily look their age. Concepts such as ‘thin body build’ have fuzzy boundaries. One person’s thin body is another’s medium build. Finally, witnesses err even on clearer concepts, such as eye color.

There is also mounting evidence that people do not remember a face by its parts, but rather by how it looks in its entirety. In addition, there is research evidence to show that even giving a verbal description of the culprit may interfere with the witness’s ability to later recognize him or her.

An alternative method would be to categorize photographs on the basis of their overall similarity, which would be more in keeping with recognition processes. A number of computerized techniques are available that can accomplish this task. However, two issues remain. First of all, the test of these methods has been to find a person’s photograph using a different photograph of the same person. The definition of similarity is the objective definition involving a comparison between the two photographs. The mugsearch, however, involves a subjective definition, a comparison between the memory of the witness and a photograph. Programs tested using the former definition may not be effective in accomplishing the latter task.

Second, an appropriate task must be found to connect the computer program and the witness. One suggestion has been to have the witness construct a composite, and have the computer find the photographs similar to it. However, we have noted that the composite is only a likeness of the person, not a photograph. It remains to be seen whether this will be good enough.

Another suggestion has been somehow to make direct use of similarity judgments of the witness. In one study the witness viewed the highest ranked 24 photographs at a time, choosing the most similar to the ‘culprit’. Using the similarity network, the computer pushed up in the ranking those photographs that were similar to those chosen. In this fashion, the culprit was pushed up and viewed much faster. However, the study did not test actual identifications, and another study has indicated that viewing photographs similar to the culprit will interfere with the identification. We note again the fragility of eyewitness evidence.

The Composite

The composite, interestingly, has been researched far more than the mugshot search. The most common experimental test of composites has been to put the photograph of the person whose composite was constructed among a set of other photographs. People then attempted to choose the correct photograph from the set. Experiments using this test have reached the conclusion that composites are not very good likenesses of the person. Only about 1 in 8 have been correct guesses.

Clearly, composite construction is a difficult task. The witness must first recall and then communicate to the composite constructor the various facial features. However, people are adept at neither recalling nor describing faces. The task of simply recognizing a face, required for the line-up and the mugshot search, is clearly much simpler.

One hypothesis explaining the poor performance of the composite was the inadequacy of the early, manual composite kits. The numbers of exemplars of each feature were limited, as were the means of modifying them. However, the few tests made with computerized composite programs, which have corrected these limitations, have not demonstrated better success rates.

In addition, all composite methods to date select parts of faces. As we have noted, this does not seem to be the way that people remember and recognize faces. An alternative approach would have witnesses choose photographs that are similar to the culprit. Superimposing these photographs could then create an average face.

While promising, such a technique returns us to a variant of the mugshot search to find those photographs that are similar to the culprit. The quality of the composite depends on the similarity to the culprit of the photographs found. Once we solve the mugshot search problem, adding the superimposition composite method would be simple. However, as we have noted, the mugshot search problem has yet to be solved.

Another potential avenue has been the use of caricatures, a proposal quite at variance with the superimposition idea. Superimposition involves averaging the features of a number of photographs, which of necessity results in a more average face. The caricature, on the other hand, emphasizes what is different, and creates a more distinctive face. So far, the experimental evidence evaluating this technique has been inconclusive; however, this may have resulted from lumping together different methods not equally effective.

None the less, police departments would consider a success rate of 12.5% (1 in 8) very good indeed. The composite is, after all, the last resort identification technique. The experimental test does not actually predict rate of success in the field. There are three major differences. First of all, the witness who constructs the composite in the experiment has calmly viewed the ‘culprit’s’ photograph. We have noted, however, that real world witnesses view culprits under far more demanding conditions.

On the other hand, in the experiment strangers to the ‘culprit’ are asked to recognize him or her from a set of photographs. In the real world, the police count on finding someone who knows the culprit to identify him from the composite. The experimental task is more difficult. Finally, in the real world the composite must reach the eyes of someone who knows the culprit. This may be the most difficult requirement of all.

The rate of success in the real world is only 2%. That is, only 2% of composites actually aid in some way in apprehending a suspect who later is convicted in court. In most cases in which composites are constructed, either the culprit is apprehended by other means or no suspect is apprehended at all. Furthermore, when the experimental test was used, real-life composites tended to be poorer lookalikes than those constructed in experiments. That was true also for those 2% of composites that actually aided the investigation. This suggests that real-life eyewitness conditions are indeed more difficult. Finally, composites have little likelihood of reaching people familiar with the culprit: usually only police officers see them.

In Conclusion

There is much room for improvement in today’s forensic tools for facial identification. Fortunately, new technology is now available for the line-up, the most crucial tool. Even in that area, however, the latest developments were only reported in 1998, and practice lags far behind advances reported more than 10 years earlier.

The fragility of the evidence, human eyewitness memory, is at the root of the difficulty. Time and again the methods devised to uncover the evidence have tended to destroy its value.

In addition, the forensic expertise of practitioners lags tremendously behind academic knowledge. Facial identification has yet to be acknowledged widely as a branch of forensic science. Very few practitioners in this field have professional academic degrees. Police continue to conduct line-ups that are either clearly unfair or far more dangerous than necessary. The challenge in the area of eyewitness identification today, then, is twofold: to achieve additional scientific breakthroughs; and to get these advances into the field.