Introduction

Firearms examiners conduct a variety of laboratory examinations. They identify and compare fired bullets and cartridges; they examine powder and shotgun pellet patterns; they restore obliterated serial numbers and they conduct toolmark examinations.

Examination of Weapons

For chain-of-custody purposes the complete identification of a firearm requires the following information: make or manufacturer, type (revolver, semiautomatic pistol and so forth), caliber, serial number, the model, the number of shots and the barrel length. Much of this information is stamped on the frame of the weapon. Many internal components of a firearm may also bear partial serial numbers; these should also be checked to determine if any components have been replaced. Information stamped on a firearm should not be taken at face-value. Aweapon may have been altered; it may also be a ‘bootleg’ weapon, i.e. a copy of a commercially produced weapon made by an unknown gunsmith. Some bootleg weapons even have duplicated inspectors’ proofmarks.

When weapons are submitted for microscopic comparison of their test-fired bullets with questioned bullets a number of preliminary examinations should be done. The exact nature of these will depend on the nature of the case being investigated; however, the preliminary examinations could include processing for fingerprints, examination of the interior of the muzzle of the weapon for blood and other tissues, determination of trigger pull and examination of the functioning of the weapon’s firing mechanism and safeties.

Processing for fingerprints will usually be the first of these examinations carried out. Firearms frequently do not yield fingerprints. A light coating of gun oil will obscure latent fingerprints and surfaces such as knurled grips are not conducive to the deposition of useable latent fingerprints. Nevertheless, the value of fingerprints for identification purposes is so great that latent fingerprint development should be routinely carried out when a weapon is not found in the possession of a suspect.

The bore of the weapon can be inspected with a helixometer. Contact shots, particularly to the head, can result in the blowback of blood and tissue into the muzzle. Other trace evidence may also be observed. If a shooter carries his weapon in a pocket, fibers from the pocket may find their way into the gun bore. The examination of the gun bore with a helixometer may be valuable from another perspective. It may reveal significant corrosion which may preclude meaningful microscopic comparison of test-fired bullets.

The determination of the weapon’s trigger pull is carried out with a spring gauge or by suspending increasing weight on the trigger until the firing mechanism is actuated. Some revolvers can be fired either single action (the firing mechanism is thumb-cocked and the weapon is then fired by squeezing the trigger) or double-action (a single long trigger pull rotates the cylinder, raises the hammer and then actuates the firing mechanism). Double-action trigger pulls are much larger than single-action trigger pulls; if a weapon can be fired either way both trigger pulls must be determined. The determination of trigger pulls is both a safety measure and an investigative procedure. The firearms examiner will generally test-fire the weapon and needs to be aware if the weapon’s low trigger pull makes it prone to accidental discharge. The suspect in a shooting investigation may allege that the shooting was due to an accidental discharge resulting from a low trigger pull. In cases of suspected suicide the trigger pull is also an issue: could the decedent have shot himself accidently while cleaning the weapon or did firing the weapon require a deliberate act of will?

The examination of the functioning of a weapon’s firing mechanism and safety features is both a safety measure for the firearms examiner and an investigative procedure. The firearms examiner needs to know if a weapon can be safely handled and fired before an attempt is made to test fire it. If the weapon as submitted by police investigators cannot be fired (due to missing or damaged components)that fact must be noted and the weapon rendered operable by replacement of components from the firearms laboratory’s firearms reference collection. Many weapons lack safety features, whereas others have several. The Colt M1911A1 semiautomatic pistol is an example of a weapon with several safety features. It has a grip safety which must be depressed by squeezing the grip with the firing hand before the weapon will fire. A manual safety catch on the left rear of the frame in the up or safe position both blocks the trigger and locks the pistol’s slide in the forward position. Finally, the hammer has a half-cock position. If when the pistol is thumbcocked the hammer slips before the full-cock position is reached the hammer will fall only to the half-cock position and not discharge the pistol.

It may be necessary to verify the caliber of the weapon. This can be done with precision taper gauges or by making a cast of the interior of the barrel. Other general rifling characteristics (e.g. number of lands and grooves, direction of twist of the rifling)can also be determined from a cast but are more conveniently determined from test-fired bullets.

Examination of Questioned Bullets and Cartridges

In the course of a preliminary examination of questioned bullets and cartridges the firearms examiner should note all identifying marks placed on these items by police investigators. He should also note the presence of any trace evidence on the questioned bullets. Bullets may have blood or other tissue on them. Bullets may also pick up fibers when passing through wood, clothing or other textiles. If a bullet has ricocheted off a surface there may be fragments of concrete or brick embedded in it. These bits of trace evidence may be very helpful in the later reconstruction of the shooting incident under investigation. Any patterned markings on the bullet should also be noted. These may also be significant in reconstruction of a shooting incident. Bullets have been found bearing impressions of the weave of clothing, wires in a window screen and police badges. Cartridge cases can be processed for latent fingerprints. Bluing solutions have proven useful for developing latent fingerprints on cartridge cases.

When fired bullets or cartridges are submitted for examination the firearms examiner must make an initial determination of the class characteristics of the weapon that fired them. From these class characteristics the possible makes and models of firearm that fired the bullet or cartridge can be determined.

Determination of general rifling characteristics from fired bullets

Caliber The caliber of an undamaged bullet can be determined in one of two ways: the diameter of the bullet may be measured with a micrometer; or the questioned bullet can be compared with bullets fired from weapons whose general rifling characteristics are known. If the bullet is severely deformed but unfragmented it can be weighed. This may not specify the particular caliber but will eliminate certain calibers from consideration. The weight of the bullet is also a class characteristic of the brand of ammunition. If the bullet is fragmented its possible caliber may still be determined if a land impression and an adjacent groove impression can be found. The sums of the widths of a land and impression and an adjacent groove impression have been tabulated for a large number of different makes and models of firearms. The specific caliber of the bullet will not in general be determined, but many calibers will be eliminated.

Number of lands and grooves Unless a fired bullet is fragmented the number of lands and grooves can be determined by simple inspection.

Widths of the lands and grooves These may be determined using a machinist’s microscope or by comparison of the bullet with bullets fired from weapons having known general rifling characteristics.

Direction of twist of the rifling If the fired bullet is relatively undistorted the direction of twist of the rifling may be determined by noting the inclination of the land impressions with respect to the axis of the bullet: land impressions inclined to the right indicate right twist rifling, whereas land impressions inclined to the left indicate left twist rifling.

Degree of twist of the rifling This can be determined using a machinist’s microscope or by comparison of the bullet with bullets fired from weapons having known general rifling characteristics.

Determination of class characteristics from cartridges

The following class characteristics may be determined from fired cartridges: caliber; type of cartridge; shape of firing chamber; location, size and shape of the firing pin; sizes and locations of extractors and ejectors. These may be determined by visual inspection with the naked eye or with a low-power microscope.

Pitfalls in determining class characteristics from fired bullets and cartridges

Care should be taken in inferring the class characteristics of a firearm from fired bullets and cartridges. A number of devices have been developed to permit the firing of ammunition in weapons for which the ammunition was not designed. These vary from the very simple to the very complex. An example of the very simple is the crescent-shaped metal tabs inserted in the extractor grooves of 0.45 ACP cartridges (for which the Colt 0.45 caliber M1911A1 semiautomatic pistol is chambered)to enable the cartridges to be loaded in 0.45 caliber revolvers. An example of a more complex device would be a barrel insert that allows 0.32 caliber pistol cartridges to be chambered and fired in a shotgun. Field expedients can also be used to fire subcaliber rounds from a weapon. Sub-caliber cartridges can be wrapped in paper and then loaded into the chambers of a revolver. Finally, some weapons can chamber and fire cartridges of the wrong caliber. The 7.62 mm Luger can chamber and fire 9 mm parabellum rounds.

Observations of individual characteristics

In order to determine whether a questioned bullet was fired from a particular firearm the questioned bullet must be compared with bullets that have been fired from the weapon that is suspected of firing the questioned bullet. In the very early days of firearms examinations (prior to the mid-1920s)test bullets were obtained by pushing a bullet through the barrel of the weapon. However, this procedure ignores the fact that when a bullet is fired down the barrel of a firearm it may undergo significant expansion (the technical term is obturation); as a result fired bullets may be marked differently by the rifling than bullets merely pushed down the barrel. Test-fired bullets are now shot into some type of trap that permits the bullets to be recovered in a minimally distorted condition. Some laboratories use horizontal or vertical water traps. Metal boxes filled with cotton waste have also been used as bullet traps; however, cotton fibers can be abrasive to the surfaces of hot lead bullets.

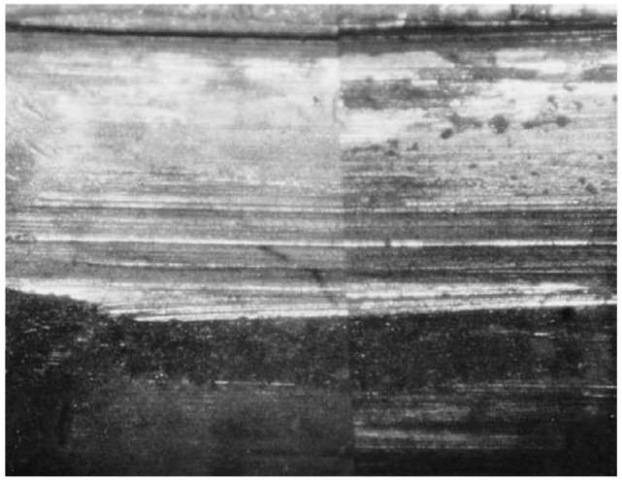

The comparison of bullets and cartridges is carried out with a comparison microscope. This actually consists of two compound microscopes connected by an optical bridge so that the images produced by each microscope can be viewed side by side. In the case of fired bullets, the firearms examiner attempts to find matching patterns of striations on both the questioned and test-fired bullets (Fig. 1). The probability of an adventitious match declines as increasing numbers of striations are matched. The probability of a random match of a pattern containing five or more closely spaced striations is negligible; however, further research is required to establish objective standards for declaring a match.

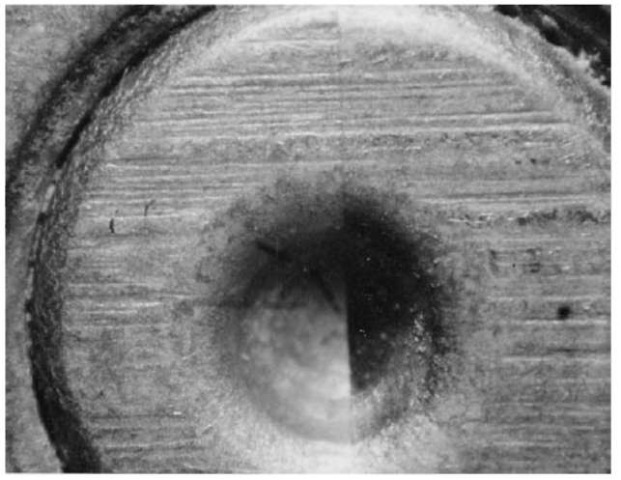

The firearms examiner can look at a variety of marks in making his comparisons of bullets: land impressions, groove impressions (often absent or insignificant on jacketed bullets), skid marks (marks made by the leading edge of the rifling as the bullet enters the rifling), shaving marks (marks made on revolver bullets when the bullets strike the edge of the forcing cone, the flared opening at the breech end of a revolver barrel)and slippage marks (marks produced when an overlubricated bullet slides down the barrel without engaging the rifling). Matching patterns of marks are also sought by the firearms examiner by comparing firing pin impressions, breechblock markings, extractor marks, ejector marks and magazine marks (Fig. 2). Extractor marks, ejector marks and magazine marks are striated marks like land and groove marks on bullets. Firing pin impressions and breechblock marks may also contain striations if these components of the firearm were finished by filing.

Figure 1 Matching striation patterns in the land impressions of two bullets fired in the same weapon.

Firearms examiners’ conclusions

Firearms examiners can render one of three opinions following the microscopic comparison of fired bullets and/or cartridges.

Figure 2 Breech block impressions on the primers of two centerfire cartridges fired in the same pistol.

1. Positive identification. The questioned firearm fired the questioned bullets and/or cartridges. In this case both the class and individual characteristics of the questioned bullets and/or cartridges match those of test-fired bullets and/or cartridges from the questioned firearm.

2. Negative identification. The questioned firearm did not fire the questioned bullets and/or cartridges. The class characteristics of the questioned firearm do not match the class characteristics of the firearm that fired the questioned bullet and/or cartridges.

3. Inconclusive. The questioned firearm could have fired the questioned bullets and/or cartridges. The class characteristics of the questioned firearm match those of the firearm that fired the questioned bullets and/or cartridges but the individual characteristics do not match. The failure of the individual characteristics to match can result from a number of circumstances. First of all, the questioned bullets and/or cartridges could have been fired in a different firearm having the same class characteristics as the questioned firearm. On the other hand the barrel of the questioned firearm may have undergone substantial alteration due to corrosion (e.g. rusting)or use (e.g. firing of a large number of rounds). Criminals may also attempt to forestall firearms examinations by replacing firing pins, filing breechblocks or altering the interior of the barrel with abrasives.

Pitfalls in comparing bullets and cartridges

Experience with the comparison of bullets fired from sequentially rifled barrels has revealed that the land and groove markings on fired bullets consist of (a) accidental characteristics (which vary from weapon to weapon and are true individual characteristics), (b) subclass characteristics (usually reflecting the particular rifling tool used to rifle the barrels)and (c)class characteristics. The problem for the firearms examiner is distinguishing type (a)marks from type (b) marks. The interpretive problem is made worse by the fact that type (b)marks are often more prominent than type (a)marks. This circumstance can lead the inexperienced firearms examiner to erroneously conclude that questioned bullets were fired from a particular weapon when in fact they were fired from a weapon rifled with the same rifling broach.

With new weapons firearms examiners have observed a ‘setting-in’ period during which sequentially fired bullets may not match one another. There is a period of use during which individual characteristics produced by the rifling operation change or even disappear. Eventually, the pattern of individual characteristics settles down and sequentially fired bullets may be readily matched. If the firearms examiner suspects that the individual characteristics in the land and groove marks produced by a weapon may not be reproducible from round to round either because the weapon is new or because the gun bore is badly corroded, a number of bullets can be test-fired through the weapon to try to match their individual characteristics before comparing them with the questioned bullets. If the test-fired bullets cannot be matched to each other there is little point in attempting to match them to the questioned bullets.

Firing pin impressions and boltface markings can also present similar interpretive patterns. Coarse markings resulting from the manufacturing process may be the same on different firing pins or breechblocks; the true individual characteristics may be very fine markings that are easily overlooked. Some weapons (e.g. 0.25 caliber auto pistols)produce very poor breechblock markings in which only one or two true individual characteristic marks may be present. Breechblock markings may be of such poor quality that no conclusions can be drawn from their comparison; in such an instance the firearms examiner may have to make use of extractor or ejector markings.

Recent Advances in Firearms Comparisons

The advent of modern high-speed digital computers has caused major changes in the field of firearms examination. At first, existing information on rifling characteristics and other class characteristics of firearms was incorporated into computerized databases that could be quickly searched for makes and models of firearms that could have fired a questioned bullet or cartridge. More recently two computer systems have been developed to capture, store and compare images of fired bullets and cartridges. DRUGFIRE® is a multimedia database imaging system developed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Mnemonics Systems Inc. This system allows the firearms examiner to capture magnified images of fired bullets and cartridges; the computer system can then compare these images with ones already stored in the system to find possible matches. The firearms examiner can then conduct a side-by-side comparison of the images to determine if indeed the items of evidence do match. IBIS (Integrated Ballistics Identification System)was developed by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF)of the US Treasury Department and Forensic Technology of Canada. IBIS consists of two modules: BULLETPROOF® for the comparison of the images of fired bullets and BRASSCATCHER® for the comparison of fired cartridges. Like DRUGFIRE®, IBIS can search for matches among previously stored images and allows the firearms examiner to compare the images of possibly matching bullets and/or cartridges. The formats of the DRUGFIRE® and IBIS systems are not compatible with one another so that images captured by one system cannot be directly imported into the other system. The great advantage of the two systems compared to conventional firearms examinations is that they allow the firearms examiner to rapidly compare bullets and cartridges test-fired from weapons seized by police with evidentiary bullets and cartridges from open shooting cases.

Miscellaneous Examinations

Firearms (as well as many other manufactured arti-cles)bear stamped serial numbers. The complete serial number is stamped on the frame of the weapon, usually directly above the trigger; partial serial numbers may also be stamped on other components of weapons (e.g. barrels). Criminals are aware that serial numbers can be used to trace a firearm to its last legal owner, and consequently, may attempt to obliterate the serial number by filing or grinding. If the filing or grinding does not remove too much metal, enough of the disordered metallic crystal structure produced by stamping the serial number may remain to permit partial or complete restoration of the serial number. Stamped serial numbers may be restored by ultrasonication, chemical or electrochemical etching or by the Magnaflux® method. Ultrasonication uses liquid cavitation to eat away the metal surface; the disordered crystal structure that underlies the stamped serial number is eaten away faster. Chemical and electrochemical etching also rely on the more rapid dissolution of the disordered metal structure. The Magnaflux® method depends on the concentration of magnetic lines of force by the disordered crystal structure. Magnaflux® powders consist of magnetic particles which cluster where the magnetic lines of force are more concentrated. Unlike ultrasonication and chemical and electrochemical etching, the Mag-naflux® method is nondestructive; however, its use is restricted to restoration of stamped serial numbers on ferromagnetic alloys.