Histology (the microscopical examination of tissues) forms an integral part of modern pathological investigation. In 1991, the British Royal College of Pathologists issued guidelines for the performance and reporting of hospital autopsies in which it was stated that ‘an autopsy is incomplete without histological examination of all major organs’. The same is true of the forensic autopsy. Histology is essential to confirm the nature of any natural disease noted during the naked eye examination, to identify those not visible to the naked eye (e.g. myocarditis) and is also applied in an endeavor to age injuries and natural disease processes such as myocardial infarction.

Over the last half century, advances in histo-pathological techniques such as enzyme histo-chemistry have been applied to forensic studies, but with very limited success. Like temperature recordings as a method for estimating postmortem interval, changes in tissues, whether due to disease or injury, are subject to numerous variables, and any conclusion drawn from such studies must be hedged about with qualifications.

General histopathology has made great strides in recent years. Immunocy to chemistry, tumor markers, aspiration techniques and flow cytometry are routinely used in diagnosis. They have proved of limited value to the forensic pathologist. Even so, this is no excuse for limiting the amount or failing to take histology as a routine. Formalin-fixed organs and tissues can be kept for weeks or months, and once appropriately embedded in paraffin wax, they can be stored more or less permanently. Ideally, blocks from the major organs, heart, lung, liver, kidney, spleen and brain, should always be taken, and hematoxylin-eosin (H & E) stained sections should be examined. Unfortunately, in many jurisdictions such comprehensive practise is limited by both cost and time. In the investigation of unexpected infant deaths, the collection of tissue should be even wider. The British Confidential Enquiry into Sudden Death in Infancy (CESDI) lays down a protocol that requires the examination of more than 40 blocks selected from specific sites within a wide range of organs.

The selection and preparation of blocks in itself poses problems. Blocks taken ‘at the table’ from the brain are of little value; the brain should be fixed for at least 8 weeks, and preferably 12 weeks, before ‘blocking out’ is undertaken. Similarly, the hearts of middle-aged or elderly subjects should not only be formalin fixed, but decalcified if an adequate examination of the coronary artery system is to be made. Every forensic pathologist should have access to a laboratory capable of cutting frozen sections, providing sledge microtome facilities for cutting large tissue blocks, and employing technicians skilled in the selection and use of special stains. Furthermore, pathologists should conform to standard site selection protocols, for example for the examination of the brain and heart, so that their work can be subjected to appropriate peer review for educational or legal reasons.

Histological examination of the heart is essential in the investigation of all transportation accidents. Myocarditis, although uncommon, may be identified as a possible cause of pilot/driver failure. Likewise, viral myocarditis may be found in both infants, and particularly in older children, where a thorough gross autopsy has failed to demonstrate a cause of death.

The histological examination of the lungs may reveal acute infection, even in those cases where microbiological studies are negative, evidence of long-standing industrial lung disease, or deposits of starch, talc and other refractile materials in intravenous drug users (Fig. 1). Other chronic illnesses predisposing to sudden death, such as asthma, are often recognized microscopically. Widespread inhalation of vomit, as opposed to agonal spillage, can be demonstrated. It should always be remembered that aspiration per se is not an adequate cause of death; the underlying reasons must be sought.

In recent years, consequent upon the work of Meadow and others, the importance of Munchausen syndrome by proxy has been more fully appreciated. Children may be harmed by their carers, who are seeking attention for themselves rather than intending to kill. Such acts, for example deliberate airway obstruction, may have fatal results.

Suffocation cannot be proved conclusively by histology. Alveolar distention and rupture may be a consequence of attempts at resuscitation. There may be some bleeding into the alveoli in natural sudden infant deaths (SIDS, cot death). However, the presence of large amounts of fresh bleeding should arouse suspicion, and if iron-laden macrophages (sidero-phages) are seen both in the alveoli and the supporting tissue this should be regarded as a marker of possible previous suffocative episodes. Hemosiderin deposits associated with delivery are thought to clear within 6-8 weeks; natural diseases such as primary idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis are rare, particularly in children under the age of 1 year. Bleeding dyscrasias show evidence of bleeding in other organs as well. Areas of pulmonary contusion, or even frank infarction, may underlie fractures of the ribs in physical child abuse (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 Intravenous drug abuse: starch granules and other contaminants at the injection site. H & E; original magnification x200.

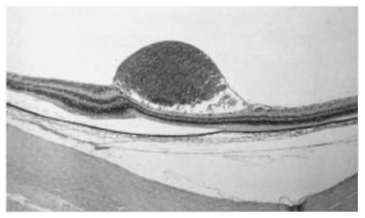

In the head-injured infant, as in those in whom head injury is suspected, histological examination of the eyes and brain is mandatory. The distribution and pattern of retinal hemorrhage seen in shaking, with or without impact, is typical, although not absolutely diagnostic (Fig. 3). Its severity correlates well with the extent of intracranial injury and brain damage.

The brain may show very little change when examined with the naked eye, but properly selected and processed sections may show lesions ranging from frank tears of tissue and subcortical hemorrhages to diffuse axonal injury, and the release of p-amylase precursor protein. Evidence of previous trauma or episodes of hypoxia may also be found.

Any subdural clot should be measured, a section examined microscopically, and any overlying neo-membranes subjected to microscopy. It has been recognized for many years that the thickness of such membranes and the degree of organization of the underlying clot may give an indication of the age of the injury. However, these are by no means reliable guides. In many cases the injury’s admitted timing bears no relation to its age assessed ‘blind’ on its histological appearance. Subdural membranes (and where appropriate, brain sections) should be stained for iron deposits with Perls’ Prussian blue reagent. The presence of hemosiderin indicates previous injury. Eye sections in such cases should also be stained for iron, although the number of positive findings is considerably lower.

Aging of injuries, both in adults and children, by microscopy is notoriously difficult. The most that one can usually say is a broad statement such as ‘the degree of organization is consistent with infliction hours rather than days previously’. Attempts to apply elegant histochemical techniques to aging of injuries have proved too expensive and unreliable for use in routine practice. Occasionally, histology differentiates between true injury and innocent lesions, such as the ‘Mongolian blue spot’ frequently present in the skin over the lower back in infants, as pronounced and obstinate lividity. It is also of value in the recognition of electrical burns and the differentiation between antemortem and postmortem thermal injury by the presence of vital reaction in the wound margins.

Figure 2 Pulmonary fat embolism following multiple fractures. Oil red O; original magnification x 250.

Figure 3 Preretinal hemorrhage in a 4-month-old child with severe acute brain injury. H & E; original magnification x200.

Histopathology is essential in the investigation of maternal death. Unless lung sections are stained appropriately, amniotic fluid embolism may be overlooked. Disseminated intravascular coagulation may also only be recognizable through the microscope after a stain for fibrin, such as Lendrum’s martius scarlet blue, has been applied. In perioperative deaths, the recognition of preexisting illness may save the surgical team from accusation of negligence – or even incompetence.

A common problem for the forensic pathologist is sudden death during or shortly after an altercation, particularly when no blows appear to have been exchanged. Careful search for signs of early myocardial ischemia should be made, using phosphotungstic acid – hematoxylin or trichrome stains. Again, a few years ago there was a fashion for using enzyme stains such as TTC and toluidine blue, but these, like so many others, work within such a broad time scale that little may, with confidence, be adduced from their use.

In cases of sudden collapse during or shortly after an assault, a posterior foss a traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage may be present. These usually result from a tear of a vertebral artery, which may be within the skull or in the high cervical spine. Not all such tears are demonstrable by flushing or radiological techniques. Step sections throughout the course of the suspect vessel may well show disruption and hemorrhage within the wall, even if the exact site of the tear cannot be demonstrated.

Histological examination is essential in the assessment of the severity of industrial lung disease. Asbestos fiber counts, carried out by those with a special interest in the techniques, are imperative where claims for compensation for lung cancer or mesothelioma are being pursued. In suspected drowning, less reliance than formerly is placed upon the presence of diatoms in lung, liver and bone, but if they are present in large number, and identical to species collected at the locus, they have some diagnostic value.

Finally, the characteristic appearance of the lungs in intravenous drug abusers has already been alluded to. Ongoing work in the UK suggests that cannabisuse may be associated with structural lung damage; prevalence of hepatitis C (and no doubt other strains) renders microscopy of drug users’ livers (as well as serology) mandatory.

Histopathology

Next post: Autopsy

Previous post: Postmortem Interval