Famed sage and vizier of the Old Kingdom

Kagemni served the rulers of both the Third (2649-2575 b.c.e.) and Fourth (2575-2465 b.c.e.) Dynasties of Egypt. He acted as the mayor of the capital of Memphis for huni (r. 2599-2575 b.c.e.) and as a vizier for snefru (r. 2575-2551 b.c.e.). Kagemni, however, is famous for his Instructions, written for him by a scribe named Kaires, a didactic text concerned with proper attitudes of service and dedication on the part of high-ranking officials. Kagemni’s tomb at saqqara, near the pyramid of teti,was L-shaped and depicted dancers, acrobats, hunting, scribes, and agricultural scenes in beautiful reliefs. There were pits included in the tomb for spirit boats as well.

Kagemni’s Instructions

A didactic text contained in the prisse papyrus. The author, a scribe named Kaires, wrote the Instructions intending to advise the vizier kagemni (fl. 26th century b.c.e.) in matters of deportment and justice befitting a high official of the pharaoh. Much of the text available is concerned with manners and social attitudes, attributes of the high-ranked individual in any organized society. For the Egyptian, however, such moderated, courteous behavior symbolized the spirit of ma’at, the orderly behavior that mirrors celestial harmony.

Kahun

A community structure at el-lahun, started by senwosret ii (r. 1897-1878 b.c.e.) of the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1783 b.c.e.), Kahun was the abode of the workers and artisans involved in royal mortuary monuments. The site was surrounded by a gated mud-brick wall and divided into three residential areas. A temple of anubis was also found on the site, and a cache of varied papyri was discovered in the temple. called Hotep-sen-wosret, “Senwosret Is Satisfied,” and located at the opening of the faiyum, the site is famous for a cache of jewelry found in the tombs of Princess (or possibly queen) sit-hathor yunet and other family members buried in the complex. The site was divided into three sections, including a necropolis area for nobles and officials and a residential area on the east and on the west. vast granaries served the entire region. The treasury of papyri at Kahun contained hundreds of texts concerning legal matters, literature, mathematics, medicine, temple affairs, and veterinarian information. The site was abandoned abruptly in a later historical period, perhaps as a result of an earthquake or some other natural disaster.

Kahun Papyrus

A document discovered in Kahun, the worker’s settlement at el-lahun in the faiyum, the papyrus dates to the reign of amenemhet ii (1929-1892 b.c.e.). One section of the text is devoted to medical procedures. Another is concerned with veterinary medicine, and a third deals with mathematics.

Kai (fl. 26th century b.c.e.)

Mortuary priest of the Fourth Dynasty

He served as a member of the mortuary cult of khufu (Cheops; r. 2551-2528 b.c.e.) at giza. Vast numbers of priests resided in the pyramidal complex of Khufu after his death, as his mortuary cult remained popular. Kai was buried in western Giza, and his tomb is called “the Nefer-tari of Giza,” “the beautiful one.” He is depicted in reliefs with his wife in the tomb chambers, and there are a false door and raised, elaborate carvings. A statue of Kai was also recovered.

Kakai (Neferirkare) (d. 2426 b.c.e.)

Third ruler of the Fifth Dynasty

He reigned from 2446 b.c.e. until his death and was probably the brother of sahure. Kakai is mentioned in the Palermo stone and in the tomb of an official named westptah. He was militarily active but left no monuments other than his tomb complex at abusir. That structure was not completed, but the temple on the site provided an important cache of papyri, dating from the reigns of niuserre (2416-2392 b.c.e.) through pepi ii (2246-2152 b.c.e.). One papyrus deals with a legacy bequeathed to his mother, Queen khentakawes (1). These papyri display the use of the Egyptian hieratic script. Kakai’s mortuary causeway at Abusir was eventually usurped by Niuserre, a later ruler who made the structure part of his own mortuary shrine.

Kalabsha

A site in northern nubia (modern Sudan), famed for a fortress and temple that were erected by tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) in the Eighteenth Dynasty era, the temple complex was fashioned out of sandstone and contained a pylon, forecourt, hypostyle hall, vestibules, and an elaborate sanctuary. The shrine was dedicated to mandulis, a Nubian deity adopted by the Egyptians. amenhotep ii, the son and heir of Tuthmo-sis iii, was depicted there in reliefs. Kalabsha was expanded in Greco-Roman times. The ptolemaic rulers (304-30 b.c.e.) refurbished the temple and added shrines to the complex with the cooperation of King arkamani of Nubia. The Roman emperor Augustus erected a temple of osiris, isis, and Mandulis. The temple was moved north when the Aswan dam was opened.

Kamose (Wadjkheperre) (d. 1550 b.c.e.) Fifteenth and last king of the Seventeenth Dynasty of Thebes He reigned from c. 1555 b.c.e. until his death, possibly in battle. Kamose was the son of Sekenenre ta’o ii and Queen ah’hotep (1) and the brother of ‘ahmose. He was raised at deir el-ballas, north of thebes, where the rulers of this dynasty had a royal residence. During his youth he was also trained in royal and court matters by his grandmother, Queen tetisheri.

The Thebans went to war with the hyksos when apophis (a Hyksos ruler of the contemporary Fifteenth Dynasty at avaris) insulted Sekenenre Ta’o II. The The-bans gathered an army and set out to rid Egypt of foreigners and their allies. Kamose came to the throne when sekenenre Ta’o ii died suddenly, and he took up the war with enthusiasm. it is possible that he married his sister, ‘ahmose-nefertari, who became the wife of ‘Ahmose when Kamose died. The elders of Thebes counseled against the war, stressing the fact that Avaris and Thebes had been at peace for decades. Kamose rebuked them, however, declaring that he did not intend “to sit between an Asiatic and a Nubian” (the Hyksos in Avaris and the Nubians in modern sudan below the first cataract). He vowed to renew the war and to rid Egypt of all alien elements.

The Thebans made use of the horse and chariot, introduced into the Nile Delta by the Hyksos when they began to swarm into Egypt in the waning days of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) and in the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1550 b.c.e.). The Thebans had lightened the chariots for maneuverability and had trained troops in their use. At the same time, Kamose had enlisted a famous fighting machine for his cause. When he went into battle, the medjay Nubian troops were at his side. These Nubians loved hand-to-hand combat and served as scouts and as light infantry units, racing to the front lines of battle and striking terror into the hearts of enemies. Kamose caught the Hyksos off guard at nefrusy, a city north of hermopolis, with a cavalry charge. After his first victory, he moved his troops into the Oasis of baharia, on the Libyan or Western Desert, and struck at the Hyksos territories south of the Faiyum with impunity.

At the same time he sailed up and down the Nile in upper Egypt to punish those who had been traitorous to the Egyptian cause. one military man was singled out for particularly harsh treatment, and Kamose was proud that he left the man’s wife to mourn him on the banks of the Nile. some documents state that Kamose was within striking distance of Avaris when he died of natural causes or battle wounds. Apophis had died just a short time before. A stela discovered in karnak provides much information about this era.

The mummy of Kamose was discovered in a painted wooden coffin at dra-abu el-naga, but it was so poorly embalmed that it disintegrated when it was taken out of the coffin. The state of the body indicates that Kamose died in the field or in an encampment some distance from Thebes and the mortuary establishment. This warrior king left no heirs and was succeeded by his brother, ‘Ahmose, of the famed Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 b.c.e.) and the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.).

Kamtjenent (fl. 24th century b.c.e.)

Prince of the Fifth Dynasty

He was the son of izezi (Djedkare) (r. 2388-2356 b.c.e.). Not the heir to the throne, Kamtjenent served as a military commander in foreign campaigns. He was buried near his father in saqqara.

Kamutef (Kemutef)

An ancient Egyptian creator deity, considered a form of the god Amun. A temple was erected on the west bank of thebes to honor Kamutef. The temple was designed as a replica of the primeval mound of creation. An image of Kamutef was displayed, called “the Amun of the Sacred Place.” Every 10 days or so, this temple was visited by a statue of amun from Thebes. Kamutef was a serpentine figure in some periods.

Kaneferre (d. c. 2040 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the Ninth Dynasty His name translates as “Beautiful is the soul of Re.” Kaneferre’s reign is not well documented, but the famed ankhtify served him, and he is mentioned in a tomb at moalla. His burial site is unknown.

Kap

This is a term recorded in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) texts, including one in the tomb of amenhotep, son of hapu. Egyptian officials claimed to know “the secrets of the Kap” or were called a “child of the Kap.” it was probably a military program used to educate high-ranking individuals, including Nubian princes (from modern Sudan), taken to thebes to be trained in Egyptian traditions. such princes were given priority in government posts because they ranked as “children of the Kap.”

Kapes (fl. 10th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

She was the consort of takelot i (r. 909-883 b.c.e.) and probably of Libyan or meshwesh descent. Kapes was an aristocrat from bubastis. She was the mother of osorkon ii (r. 883-855 b.c.e.).

Karanis

A site in the faiyum region founded in the Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.), Karanis had a population of about 3,000 on the banks of Lake moeris. Two limestone temples were erected on the site, dedicated to the crocodile gods pnepheros and petesouchus. A smaller temple honoring isis and sobek was also discovered at Karanis.

Karaotjet (fl. ninth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

She was the consort of osorkon iii (r. 777-749 b.c.e.). Karaotjet bore a daughter, shepenwepet (1), who became a god’s wife of amun at thebes, takelot iii, and rudamon.

Karnak

This is the modern name for an ancient religious complex erected at thebes in Upper Egypt. Called Nesut-Tawi, “the Throne of the Two Lands,” or Ipet-Iset, “The Finest of Seats,” it was the site of the temple of the god amun at Thebes. Karnak remains the most remarkable religious complex constructed on earth. its 250 acres of temples and chapels, obelisks, columns, and statues, built during a period of 2,000 years, incorporate the finest aspects of Egyptian art and architecture and transformed the original small shrines into “a great historical monument of stone.”

Karnak was originally the site of a shrine erected in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.), but many rulers of the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) repaired or refurbished the structure. it was designed in three sections. The first one extended from the northwest to the southwest, with the second part at right angles to the original shrine. The third section was added by later rulers and completed the complex.

The plan of the temple dedicated to the god Amun, evident even in its ruined state, contained a series of well-coordinated structures and architectural innovations, all designed to maximize the strength of the stone and the monumental aspects of the complex. Karnak, as all other major temples of Egypt, was graced with a ramp and a canal leading to the Nile, and this shrine also boasted rows of ram-headed sphinxes at its entrance. At one time the sphinxes joined Karnak and another temple of the god at luxor, to the south.

The entrance to Karnak is a gigantic pylon, 370 feet wide, which opens onto a court and to a number of architectural features. The temple compound of ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) of the Twentieth Dynasty is located here, complete with stations of the gods, daises, and small buildings to offer hospitable rest to statues or barks of the various deities visiting the premises. The pylon entrance, unfinished, dates to a period after the fall of the New Kingdom. just inside this pylon is a three-chambered shrine erected by seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.) of the Nineteenth Dynasty for the barks of the gods Amun, mut and khons (1).

The shrine of Ramesses III of the Twentieth Dynasty is actually a miniature festival hall, complete with pillars and elaborate reliefs. The so-called bubastite portal, built in the Third Intermediate Period, is next to the shrine. The court of Ramesses iii was eventually completed by the addition of a colonnade, and a portico was installed by horemhab (r. 1319-1307 b.c.e.), the last ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty

The second pylon in the structure, probably dating to the same dynastic era and refurbished by the pharaohs of the Nineteenth Dynasty, is graced by two colossi of ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.), and a third statue of that king and his queen-consort stands nearby. This second pylon leads to a great hypostyle hall, the work of Seti I and Ramesses II, where 134 center columns are surrounded by more than 120 papyrus bundle type pillars. Stone slabs served as the roof, with carved stone windows allowing light to penetrate the area. The Ramessid rulers decorated this hall with elaborate reliefs. At one time there were many statues in the area as well, all removed or lost now. of particular interest are the reliefs discovered in this hall of the “Poem of pentaur,” concerning military campaigns and cultic ceremonies of Egypt during its imperial period. The hittite alliance is part of the decorative reliefs.

The third pylon of Karnak was erected by amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty The porch in front of the pylon was decorated by seti i and Ramesses II. At one time four obelisks stood beside this massive gateway. One remains, dating to the reigns of tuthmosis i (1504-1492 b.c.e.) and tuthmosis iii (1479-1425 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty. A small area between the third and fourth pylons leads to precincts dedicated to lesser deities. The fourth pylon, erected by Tuthmosis I, opens into a court with Osiride statues and an obelisk erected by hatshepsut (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.). Originally part of a pair, the obelisk now stands alone. The second was discovered lying on its side near the sacred lake of the temple complex. Tuthmo-sis I also erected the fifth pylon, followed by the sixth such gateway, built by Tuthmosis III.

These open onto a courtyard, a Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) sanctuary, the Djeseru-djeseru, the holy of holies. statues and symbolic insignias mark this as the core of the temple. The sanctuary now visible was built in a late period, replacing the original one. A unique feature of this part of Karnak is the sandstone structure designed by Hatshepsut. she occupied these chambers on occasion and provided the walls with reliefs. Tuthmosis III added a protective outer wall, which was inscribed with the “annals” of his military campaigns. This is the oldest part of Karnak, and much of it has been destroyed. The memorial chapel of Tuthmosis iii is located just behind the court and contains chambers, halls, magazines, and shrines. A special chapel of Amun is part of this complex, and the walls of the area are covered with elaborate reliefs that depict exotic plants and animals,duplicates in stone of the flora and fauna that Tuthmosis iii came upon in his syrian and palestinian military campaigns and called “the Botanical Garden.”

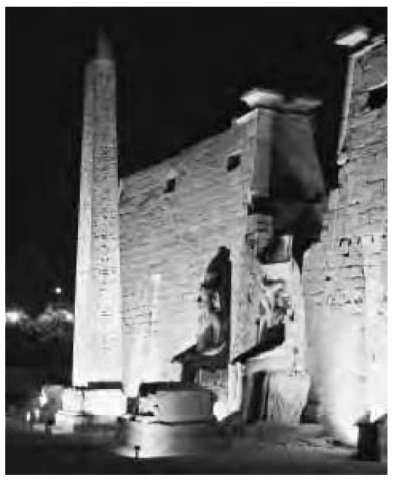

An impressive nighttime image of the great temple complex at Karnak.

A number of lesser shrines were originally built beyond the limits of the sanctuary, dedicated to ptah, osiris, khons (1), and other deities. To the south of the sixth pylon was the sacred lake, where the barks of the god floated during festivals. A seventh pylon, built by Tuthmosis III, opened onto a court, which has yielded vast amounts of statues and other relics from the New Kingdom. Three more pylons complete the structure at this stage, all on the north-south axis. Some of these pylons were built by Horemhab, who used materials from akhen-aten’s destroyed temple complex at ‘amarna. A shrine for Khons dominates this section, alongside other monuments from later eras. A lovely temple built by senwosret i (r. 1971-1926 b.c.e.) of the Twelfth Dynasty was discovered hidden in Karnak and has been restored. A shrine for the goddess Mut, having its own lake, is also of interest.

Karnak represents faith on a monumental scale. Each dynasty of Egypt made additions or repairs to the structures, giving evidence of the Egyptians’ fidelity to their beliefs. Karnak remains as a mysterious enticement to the world of ancient Egypt. One Karnak inscription, discovered on the site, is a large granite stela giving an account of the building plans of the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty. A second stela records work being done on the ptah shrine in the enclosure of the temple of Amun.

The Karnak obelisks vary in age and some are no longer on the site, having been moved to distant capitals. Those that remain provide insight into the massive quarrying operations conducted by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.). The Karnak pylon inscriptions include details about the New Kingdom and later eras and provide scholars with information concerning the rituals and religious practices as well as the military campaigns of the warrior kings of that period.

A Karnak stela, a record of the gifts given to Karnak by ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.), presumably in thanksgiving for a victory in the war to oust the Asiatics, is a list of costly materials. ‘Ahmose provided the god Amun with golden caplets, lapis lazuli, gold and silver vases, tables, necklaces, plates of gold and silver, ebony harps, a gold and silver sacred bark, and other offerings. The Karnak King List, discovered in the temple site, is a list made by Tuthmosis iii. The document contains the names of more than 60 of ancient Egypt’s rulers, not placed in chronological order.

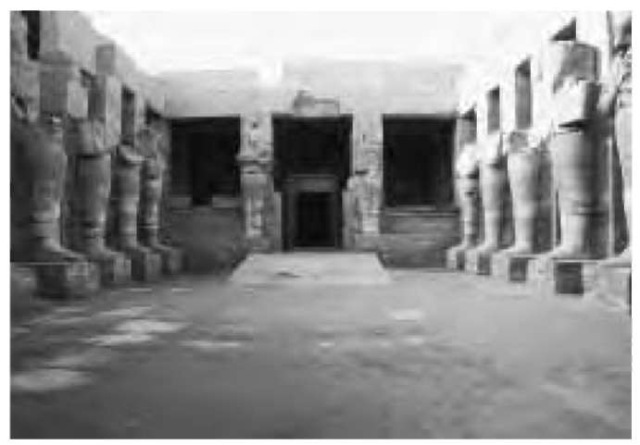

A section of the great religious complex at Thebes, dating to the Ramessid era, dedicated to the god Amun and other members of Egypt’s pantheon of deities.

Thought. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 1999; Road to Kadesh: a Historical Interpretation of the Battle Reliefs of King Sety I at Karnak. Chicago: Oriental Inst., 1990.

Karnak cache

A group of statues, vast in number, that were discovered in the courtyard of the seventh pylon of that religious complex. These statues, now in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, probably were buried during a time of crisis for security reasons. They span many eras of Egyptian religious endeavors at the great temple of Karnak at thebes.

Karomana (1) (Karomama, Kamama, Karomet)(fl. 10th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

She was the consort of shoshenq i (r. 945-924 b.c.e.) and the mother of osorkon i and Prince iuput.

Karomana (2) (Karomama) (fl. 10th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty She was the consort of osorkon i (r. 924-909 b.c.e.), and probably his sister. Karomana was the mother of takelot i.

Karomana (3) (fl. ninth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

She was the consort of shoshenq ii (r. 883 b.c.e.). Karomana was buried in leontopolis.

Karomana (4) (fl. ninth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

The consort of osorkon ii (r. 883-855 b.c.e.), Karomana was the mother of takelot ii (r. 860-835 b.c.e.).

Karomana (5) (Karomana-Merymut) (fl. ninth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty She was the consort of takelot ii (r. 860-835 b.c.e.) and the mother of osorkon iii. Karomana may have been the mother of shoshenq iii as well and was reportedly a god’s wife of amun for a time.

Karomana (6) (fl. eighth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-second Dynasty

She was probably the consort of shoshenq iv and the mother of osorkon iv (735-712 b.c.e.). Karomana was buried at To-Remu, leontopolis.

ka servant

The mortuary priest contracted by the deceased and his or her heirs to perform services on a daily basis for the ka. such priests were normally paid by a prearranged endowment, sometimes recorded in “tomb balls” placed at the gravesite. The mortuary temples in the complexes of royal tombs had altars for the services of these ka servants. A SERDAB, a chamber containing statues of the deceased and designed so that the eyes of each statue could witness the daily rituals, were included in the tombs from an early period. The Egyptian dread of nothingness predicated the services of the ka servants. They said the names of the deceased aloud as they conducted rituals, thus insuring that the dead continued to live in the hearts and minds of the living and therefore maintained existence.

Kashta (Nima’atre) (d. 750 b.c.e.)

Founder of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty

He reigned from 770 b.c.e. until his death in gebel barkal in nubia (modern Sudan), but he was accepted in much of Upper Egypt. Kashta’s queen was pebatma, probably the mother of his sons, piankhi (1) (Piye) and shabaka. His sister or daughter, amenirdis (1), was named god’s wife of amun, or “Divine Adoratrice of Amun,” at Thebes, and was adopted by shepenwepet (1). Piankhi succeeded Kashta, who during his reign erected a stela to the god khnum on elephantine Island. The reign of osorkon iii (777-749 b.c.e.) in the Delta’s Twenty-third Dynasty, a contemporary royal line, was threatened by Kashta’s move into upper Egypt.

Kassites

A people that are recorded as originating in Central Asia, taking the city of Babylon c. 1595 b.c.e. The Kassites ruled Babylon for almost three centuries, restoring temples at Ur, Uruk, and Isin, as well as at Dur-Kurigalzu, modern Agar Quf in Iraq. By the 13th century b.c.e., the Kassite Empire covered most of Mesopotamia, but it was overrun by the Elamites c. 1159 b.c.e. Several Kassite rulers had dealings with Egypt, and some are mentioned in the ‘amarna correspondence. Burna-Buriash II (1359-1333 b.c.e.), Kurigalzu I (c. 1390 b.c.e.), and Kuri-galzu II (1332-1308 b.c.e.) are among those kings.

Kawit (1) (Khawait, Kawait) (fl. 24th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Sixth Dynasty

She was the consort of teti (r. 2323-2291 b.c.e.). Her

pyramidal complex in saqqara has been eroded over the

centuries.

Kawit (2) (Khawait, Kawait) (fl. 21st century b.c.e.)

Royal companion of the Eleventh Dynasty She was a member of the harem of montuhotep ii (2061-2010 b.c.e.). Her burial chamber was part of Montuhotep Il’s vast complex at deir el-bahri on the western shore of thebes. This tomb contained elaborate and stylish scenes of her cosmetic rituals. Kawit had a sarcophagus that designated her as “the Sole Favorite of the King,” a distinction often repeated in other female burials in Deir el-Bahri.

Kay (fl. 25th century b.c.e.)

Priest of the Fourth Dynasty (2575-2465 b.c.e.) who was beloved by many rulers of Egypt

Kay served snefru, khufu (Cheops), ra’djedef, and khafre (Chephren). Revered for his years of faithful service, Kay was buried in giza beside the Great pyramid of Khufu. His tomb contains beautiful depictions of daily life, funerary scenes, and human experiences.

Kebawet

An early goddess in Egypt, worshiped only locally and disappearing as the deities of the land assumed roles in the government and in daily life, Kebawet was called the goddess of “cold water libations,” an element considered vital for paradise. she was thus part of the mortuary rituals, representing desired attributes of amenti in the West.

Kebir (Qaw el-Kebir)

A necropolis on the eastern shore of the Nile at assiut. Tombs of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) nomarchs were discovered there. Three elaborate mortuary complexes at Kebir contained sophisticated architectural elements, including corridors, porticos, shrines, and terraces.

“Keeper of the Door to the South”

This was the title given to the viceroys of Kush (Nubia, now modern Sudan). The governors of aswan carried the same title. The rulers of the Eleventh Dynasty (2040-1991 b.c.e.) and the Seventeenth Dynasty (1640-1550 b.c.e.), the lines of Inyotefs and the Ta’os at thebes, assumed the same role in their own eras. controlling upper Egypt as contemporaries of the Delta or northern dynasties, these Thebans ruled as far south as the first cataract of the Nile or beyond.

Kemanweb (Kemanub) (fl. 19th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twelfth Dynasty

She was probably the consort of amenemhet ii (r. 1929-1892 b.c.e.). Kemanweb was buried in Amenemhet Il’s mortuary temple at dashur, entombed in the main structure there. Her coffin was a single trunk of a tree, hollowed out and inscribed.

Kemenibu (fl. 17th century b.c.e.)

Mysterious royal woman of the Thirteenth Dynasty

A queen, she was a consort of one of the rulers of the Thirteenth Dynasty. Kemenibu’s tomb was discovered in the complex of amenemhet ii (r. 1929-1892 b.c.e.) of the Twelfth Dynasty at dashur.

Kem-wer

This was a bull, called the “Great Black One,” established at athribis in the earliest eras of Egyptian history. obscure observances were conducted in honor of this animal in the city, and Kem-wer remained popular for centuries. See also apis; bulls.

Kemyt

A scholar’s text cited in the SATIRE ON TRADES, dating to the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1783 b.c.e.) or possibly earlier. Surviving copies were found in ‘amarna and in other New Kingdom sites. The Kemyt was a standard school text in use by the Twelfth Dynasty, particularly for scribes. in vertical columns, the text provided basic training in the hieratic script.

Kenamun (1) (fl. 15th century b.c.e.)

Military naval superintendent of the Eighteenth Dynasty

Kenamun started his career by serving as the chief steward of amenhotep ii (r. 1427-1401 b.c.e.) and then was appointed the superintendent of peru-nefer, the naval base near Memphis. Kenamun’s mother, Amenenopet, was a royal nurse. Kenamun had a special glass SHABTl given to him by the pharaoh.

Kenamun (2) (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Mayor of Thebes in the Eighteenth Dynasty

He held this important office during the reign of amenhotep iii (1391-1353 b.c.e.). thebes was a powerful city in this era, serving as the capital of the Egyptian Empire. Kenamun was buried on the western shore of Thebes.

kenbet

The local and national courts of Egypt that evolved from the original court called the seru, a council of nome elders who rendered judicial opinions on cases brought before them, the kenbet replaced the former council, the djadjat, of the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.) and made legally binding decisions and imposed penalties on the nome level. The great kenbet, the national equivalent of modern supreme courts, heard appeals and rendered legal decisions on all cases except those involving treason or any other capital offense. These matters were not within the jurisdiction of any legal institution but were reserved to the ruler alone. See also “eloquent peasant”; legal system.

kenken-ur

A term used to designate the Great Cackler, the mythological cosmic layer of the cosmic egg, the Goose-goddess, Ser-t. The term kenken-ur was associated as well with the earth deity, geb, who sired osiris, isis, set, and nephthys. His wife was nut, the sky Keper (fl. 12th century b.c.e.) Ruler of the land of Libya in the reign of Ramesses III (1194-1163 b.c.e.) He faced an invasion of his domain and then united with his enemies to assault Egypt. The meshwesh, a tribe living deep in the Libyan Desert, allied themselves with Keper and his son, Meshesher, when they entered his territory. In turn, Keper and the Meshwesh invaded Egypt. They entered the canal called “the Water of Re,” in the western Delta. Ramesses III attacked the invading force and routed them, chasing the enemy some 12 miles into the Libyan Desert. Meshesher was captured along with 2,052 prisoners, while 2,175 Libyans were slain. A wall text and a relief at medinet habu document Keper’s pleas for his own life, apparently in vain. See also sea peoples.

Kermeh (Kerma) A site and culture at the second cataract of the Nile in Kush, or nubia (modern Sudan), The region was somewhat controlled by Egypt as early as the Middle Kingdom (2048-1640 b.c.e.). amenemhet i (r. 1991-1962 b.c.e.) of the Twelfth Dynasty erected a fortress at Kermeh. In time the people of Kermeh became a powerful state, ruled by kings who used the traditions of Egypt for their religious and national priorities. These royals were buried in circular mounds, accompanied by slain courtiers and servants. During the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1550 b.c.e.), the Kermeh people allied themselves with the hyksos, the Asiatics who ruled from avaris in the Delta. Taking over the Egyptian fortresses on the Nile, the people of Kermeh advanced toward Egypt. One group led by a’ata was halted by ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.) and slain. Egypt maintained control of Kermeh for centuries afterward.

Kewab (fl. 26th century b.c.e.)

Prince of the Fourth Dynasty, possibly murdered by a rival heir to the throne

He was a son of khufu (Cheops; r. 2551-2528 b.c.e.) and Queen meritites (1) and the designated heir to the throne. Kewab married hetepheres (2), a royal heiress. They had a daughter, merysankh (3) and other children. Kewab died suddenly, possibly the victim of an assassination, as the royal family was composed of two different factions at the time.

He was depicted as a portly man in Queen Mery-sankh’s tomb, a site prepared for her mother and given to her when she died at a relatively young age. Kewab was buried in a mastaba near the Great pyramid of Khufu. His mortuary cult was popular in Memphis, and in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.), Prince kha’emweset (1), a son of Ramesses II, restored Kewab’s statue.

Kha (fl. 15th century b.c.e.)

Official of the Eighteenth Dynasty

He served amenhotep ii (r. 1427-1401 b.c.e.) and his two successors, tuthmosis iv (r. 1401-1391 b.c.e.) and amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.). Kha was an architect involved in mortuary complexes for the royal families. He was buried at thebes.

Kha’ba (Tety) (d. 2599 b.c.e.)

Fourth ruler of the Third Dynasty

He reigned from 2603 b.c.e. until his death. His name meant “the Soul Appears,” and he was the successor of sekhemkhet on the throne. Kha’ba was listed on stone vessels in saqqara and in the tomb of sahure (r. 2458-2446 b.c.e.). He built the pyramid at zawiet el-aryan, between giza and abusir. A layered pyramid, originally with seven steps, Kha’ba’s tomb contained a sarcophagus of alabaster. The pyramid was never completed and apparently was not used. mastaba tombs were erected near his pyramid, probably for his royal family members and high-ranking courtiers.

Khababash (fl. c. 338 b.c.e.)

Egyptian rebel mentioned in the “Satrap Stela”

Considered a successor to nectanebo ii (r. c. 360-343 b.c.e.), Khababash led a revolt against the Persians sometime around 338 b.c.e. ptolemy i soter (r. 304-284 b.c.e.) was the satrap (provincial governor) of Egypt for philip iii arrhidaeus (r. 333-316 b.c.e.) and Alexander iv (r. 316-304 b.c.e.) when he issued the stela to link his own rule to that of Khababash, who was a national hero. Khababash ruled over a small region of Egypt, during the persian occupation of the Nile valley. He had the throne name of senentanen-setepenptah. See also rebels of egypt.

Khabrias (fl. fourth century b.c.e.)

Greek mercenary general

He commanded the mercenary forces serving hakoris (r. 393-380 b.c.e.) of the Twenty-ninth Dynasty. An Athenian, Khabrias resided in Egypt, and his daughter, ptolemais (1), married an Egyptian general named Nakhtnebef. Nakhtnebef became the founder of the Thirtieth Dynasty, as nectanebo i. General Khabrias was recalled to Athens c. 373 b.c.e.

Kha’emhet (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Scribe and overseer of the Eighteenth Dynasty

He served amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.). Kha’emhet was a court scribe and an overseer of the royal granaries of thebes. He was buried in a necropolis on the western shore at Thebes. His tomb has fine low reliefs that depict Amenhotep III as a sphinx. Also portrayed are Osirian funeral rituals, scenes of daily life, and court ceremonies.

Kha’emweset (1) (fl. 13th century b.c.e.)

Prince of the Nineteenth Dynasty, called “the Egyptologist” He was a son of ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.) and Queen isetnofret (1), becoming the heir to the throne upon the death of three older brothers. Kha’emweset served as the high priest of ptah and as the overseer of the interment of the sacred apis bull in saqqara. He devoted countless hours to restoring monuments and was revered for his magical skills.

Prince Kha’emweset was depicted in the relief of a battle scene as accompanying Ramesses ii on an expedition to nubia (modern Sudan). In that scene Ramesses II was identified as a prince, not having succeeded seti i at the time. Training in battle and in administrative affairs in the royal court was followed by further education in sacred matters in the temple of the god ptah in memphis.

When Kha’emweset was named heir to the throne in regnal year c. 43 of Ramesses II, he was already at an advanced age and died in regnal year 55. His tomb has not been identified, but a mummy found in the granite tomb of apis Bull XIV has raised possibilities as to the prince’s final resting place. A golden mask believed to belong to Kha’emweset was discovered in the catacombs of the serapeum in Saqqara. The prince and his mother, Queen Isetnofret, were possibly buried nearby.

Kha’emweset (2) (fl. 12th century b.c.e.)

Prince of the Twentieth Dynasty

He was a son of ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.). Kha’emweset was depicted on the walls of medinet habu with 19 of his brothers. His service to Egypt was conducted as a priest of the god ptah. The prince’s tomb was built in the valley of the queens, on the western shore of thebes, and has a square burial chamber with side chapels. paintings in the tomb depict Ramesses iii introducing Kha’emweset to the deities of the tuat, or Underworld.