The Middle Kingdom came to an end because of the growing presence of eastern Asiatics in the land. A sage of the period lamented the signs of the “desert,” the bedouins from the east, in the Nile Valley. Actually, the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1550 b.c.e.) was a time of political rather than social upheavals. The people watched the hyksos, the dominant Asiatics, assume power and erect a capital, but the viziers and other officials maintained order in the north while the Thebans controlled upper Egypt.

Rival dynasties emerged in the Delta, but the Hyksos maintained a firm grip on their holdings and were careful to uphold ancient traditions alongside their alien architecture and art. They also opened eastern borders, and many groups in the Levant deemed themselves Egyptians as a result. In the south, Nubians entered Egypt to serve under the Theban rulers of the Seventeenth Dynasty (1640-1550 b.c.e.), who would rise up to restore a united land.

ta’oii (r. c. 1560 b.c.e.) and his son, kamose (r. 1555-1550 b.c.e.), led the campaign to oust the Hyksos. They faced complacent Egyptians who prospered under the Asiatic rulers and had no compelling reason to see Egypt united under Thebans as a consequence. ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.) came to the throne after his brother, Kamose, and within a decade he was on the march north. tetisheri, ah’hotep (1), and ‘ahmose-nefertari were queens of Thebes during the period. They were able to attract the allegiance of the people and to lead the nation into the famed era of the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.). The Tuthmosid and Ramessid dynasties provided the leadership for Egypt’s empire in this period, and the average citizen of the Nile assumed new imperatives as a result.

THE NEW KINGDOM PERIOD

The role of the divine pharaoh, a truly Egyptian god-king, signaled the restoration of ma’at throughout the land. The people knew that military campaigns conducted by such rulers not only expanded the nation’s holdings as an empire but kept Egypt secure. The rise of the cult of Amun at Thebes revived the nation spiritually, and the nomes remained cooperative, sending their ablest young men into the service of the gods or the pharaoh. Educational institutions thrived, medicine and the arts and architecture prospered, and the standing armies patrolled entire regions. Such armies no longer depended upon the cooperation of nomarchs but remained on duty and prepared for far-flung campaigns in the empire. conscription became part of the commoners’ lives at the same time.

commoners who were not educated tilled the soil and celebrated an extraordinary number of religious festivals throughout the year. Women had increased legal rights and served in the temples of Egypt as chantresses, with some becoming part of the “harem” of Amun.

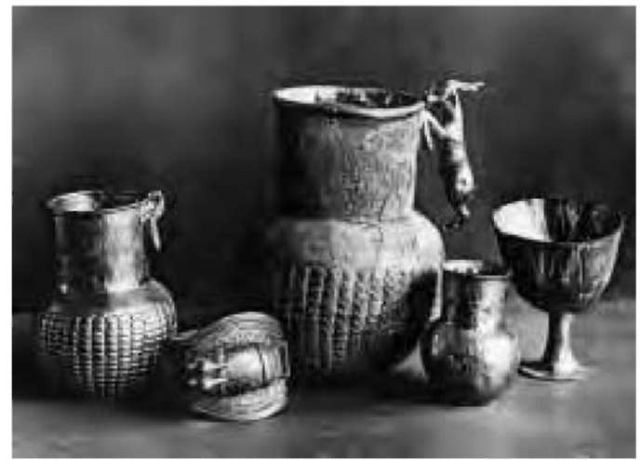

Golden tableware that dates to the Nineteenth Dynasty.

At the same time, Egyptians became rather sophisticated and cosmopolitan. Foreigners, who had come to Egypt as a result of trade or conquest, were not viewed with disdain by the average person but accepted on their own terms. The traditional caste system imposed by the nomes disintegrated as well, and a definite middle class of traders, craftsmen, and artisans arose in this era.

The period of ‘amarna and the reign of akhenaten (1353-1335 b.c.e.) proved disastrous for the average Egyptian and the empire. The people remembered tuth-mosis i (r. 1504-1492 b.c.e.) and tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) and had thrilled at the sight of amen-hotep II (r. 1427-1401 b.c.e.). The new ruler, however, Akhenaten, was a solitary man, who closed the traditional temples of the old gods and made aten the deity of the land. The Egyptians did not accept him.

The coronation of horemhab (r. 1319-1307 b.c.e.) came as a relief, and the rise of the Ramessids rejuvenated the land. seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.), ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.), and ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) stood as true pharaohs for the people, and the decline of their era filled most with a sense of dread. Famines, droughts, lawlessness, and suffering followed, and one year was called “the Year of the Hyena” because of the miseries inflicted upon the land.

THE THIRD INTERMEDIATE PERIOD

The collapse of the Ramessids in 1070 b.c.e. opened the Third Intermediate Period that lasted until 712 b.c.e. The rulers of the Twenty-first Dynasty and the Amunite priests of Thebes maintained familial ties but separate spheres of authority. This was not a time of calm or dedication. These priests and rulers were reduced to usurping the monuments and mortuary regalias of previous pharaohs. Thebes rioted, and nomes withdrew their support in critical ventures. Nubia and the eastern empire were lost to Egypt, and the people experienced no sense of unity or destined powers.

The loss of festivals and rituals altered the social fabric of Egypt in the same era. Even the cultic ceremonies celebrated in this era could only mimic the splendors of past rites. Cultic experiences were vital to the Egyptians, who did not want to delve into the theological or esoteric lore. Seeing the image of the god, marching through temple courts and singing the popular hymns of the day, was enough to inspire the average man or woman on the Nile. herihor and other Amunite leaders began a renaissance, but the dynasty could not sustain power.

The true renaissance came with the Libyans of the Twenty-second Dynasty (945-712 b.c.e.). The Egyptians for the most part accepted the rule of this foreign clan, the descendants of the meshwesh Libyans who had fought for a place in the Nile Valley during the New Kingdom era. shoshenq i (r. 945-924 b.c.e.) appeared as a new warrior pharaoh, expanding the nation’s realms. He refurbished temples and restored a certain level of piety in the land. At his death, however, the dynasty was splintered by the Twenty-third (828-712 b.c.e.), Twenty-fourth (724-712 b.c.e.), and Twenty-fifth (770-712 b.c.e.) Dynasties.

THE LATE PERIOD

These doomed royal lines had limited authority and no following among their fellow Egyptians who watched the Nubians gain power. piankhi (r. 750-712 b.c.e.) proclaimed the Twenty-fifth Dynasty the bearer of Amun and the restorer. He soon controlled all of Egypt, as the people supported his religious revival and were subdued by his barbaric cruelty. Those Egyptians who opposed him and his Nubian forces ended up as slaves, a new policy in the nation.

This Nubian line was interrupted by a brief occupation of the Nile Valley by the Assyrians, led by essarhad-don. taharqa (r. 690-664 b.c.e.) fled to Nubia and then fought to regain his throne. There was no massive uprising of the Egyptians to aid him in his quest because the battle had nothing to do with good versus evil or the restoration of ma’at. The people understood that this was a contest between Assyrians and Nubians, played out on the banks of the Nile. The mayor of Thebes at the time, mentuemhat, represented his fellow countrymen as the foreign armies swept across the land. A ranking priest of Amun at Thebes and called “the Prince of the city,” Mentuemhat watched events unfold but maintained his routines and his obligations. He appeared so able, so competent, that the Assyrians withdrew from Thebes, leaving him in charge of the area.

Remarkably, no Egyptian rebellion arose to eject the foreign occupiers. The population of that era did not possess the same spirit as their ancestors. They retreated,instead, aware of the impact of alien intruders and yet unmoved by the march of invading forces. A spirit of renewed nationalism was developing in the nomes, however, and a cultured revival was evident in the far-flung regions that did have direct contact with the political seats of power. They equated all of the dynastic forces at war within the land as enemies, the spawn of set, and sought peace and the old ways within their nomes.

This was a peculiar social reaction, but it was deeply rooted in the traditions of Egypt. The native people feared chaos, recognizing it as the root of destruction in any human endeavor. The Egyptians appear to have had a growing sense of the inevitable in this historical period. Egypt was no longer safe, no longer protected by the deserts or shielded by warrior pharaohs. The clans could only protect their traditions and their spiritual lore by defending their limited resources and domains.

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty at sais offered the nation a shrewd royal line of administrators and militarily active rulers. The Persians, led by cambyses (r. 525-522 b.c.e.), put an end to this native dynasty by taking control of Egypt as the Twenty-seventh Dynasty (525-404 b.c.e.). By 404 b.c.e., the Twenty-eighth Dynasty displayed the only resistance force of the era. The Twenty-ninth (393-380 b.c.e.) and Thirtieth (380-343 b.c.e.) Dynasties followed, providing competent rulers but mandated by realities that dragged Egypt into vast international struggles. The people watched as the resources and armies of the Nile were squandered in defense of foreign treaties and alliances that offered Egypt little promise. One ruler of the era, teos (r. 365-360 b.c.e.), robbed Egypt’s temples to pay for his military campaigns beyond the nation’s borders.

THE GRECO-ROMAN PERIOD

When the Persians returned in 343 b.c.e., the Egyptian people offered no resistance. artaxerxes iii ochus led a large Persian force into the Nile Valley, and only one man, khababash, led a short-lived revolt. The arrival of Alexander iii the great in 332 b.c.e. brought joy to the Egyptians, and they greeted him as a true liberator. The Persians had been cruel taskmasters for the most part, but they had also held Egypt’s historical glories in disdain. This attitude had a chilling effect on the native people. The artistic, architectural, and agricultural achievements of Egypt drew such conquerors to the Nile, but they arrived with alien attitudes and even contempt.

Egypt was also a conglomeration of peoples in that era. Many groups had come to the land, and races mingled easily in all areas. The bureaucracy and the temples continued to function with stability because the Egyptians refused to surrender to chaos even during cruel occupations. The pattern of enduring and protecting the unseen traditions and spiritual modes of the past became the paramount activity of men and women in all areas of the land. Their ancestors had watched foreign armies come and go, while the pyramids and the temples survived and flourished. in their own eras, they were the protectors of the past.

Alexander the Great’s retinue taught the native peoples that their ancestors were wise in adopting their own defensive modes. The young conqueror was crowned as a true pharaoh, but those who followed him had no intention of reviving the past on the Nile. The Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) was another time in which the rulers and the average citizens had little or no impact upon one another.

In Alexandria, the new capital, the Ptolemies ruled as Hellenes, transporting Greek scholars, ideals, and even queens to the Nile to support their rule. Positions of power and trust rested in the hands of Greeks or Hell-enized Egyptians, and the nation became involved in Mediterranean affairs. in religious matters, the Greeks upheld the old traditions but introduced Greek deities and concepts. Even the royal cults of the rulers assumed the rigid and formalized Hellenic styles.

The Egyptians were also isolated to the traditional courts and laws of the nation. Ptolemaic law was directed toward the Greeks, while the juridical system traditional to the Nile Valley was maintained at local levels. The people seldom saw Greeks or Ptolemaic representatives, and their private lives went on with stability and calm. The pattern had been set, and it would prove successful when the Ptolemies gave way to Rome.

Octavius, who became Augustus and first emperor of Rome, understood the potential and the achievements of the Egyptians and took possession of the Nile Valley. For the empire, Egypt became the “bread basket” from which emperors fed their imperial subjects and also the strategic gateway to the Red sea and the spices and trade of the east. While inhabitants of one of the most important provinces in the empire, Egyptians went on with their lives and lived as they always had, dependent upon the abundance of the Nile.

Sokar (Seker)

An ancient Egyptian god of the Mem-phite necropolis from predynastic times, he was actually a spirit guardian of the tombs but was elevated in rank after 3,000 b.c.e. He was united with ptah and depicted as having come from that deity’s heart and mind as a force of creation. When the cult of osiris developed a triune deity, Osiris-Ptah-Sokar emerged. That trinity is called Osiris-Sokar-Asar in some lists.

Sokar’s theophany was the hawk, and his shrine and sacred bark date to the period before the First Dynasty He is represented in reliefs as a pygmy with a large head and heavy limbs, wearing a beetle on his head and standing on a cabinet, with hawks in attendance. sokar represented darkness and decay. The dead remained with Sokar until re’s light awakened them. The feast of Sokar was celebrated in the fourth year of the Second Dynasty (2770-2649 b.c.e.) and is noted in the Palermo stone. One of his litanies was included in the rhind papyrus, and he was the patron of the necropolis district of mem-phis. In the New Kingdom Period (1550-1070 b.c.e.) sokar regained popularity. in his statues the god was fashioned as a hollow mummy, containing copies of the topic of the dead or corn kernels. He was called “He Who is upon His sand,” a reference to his desert origins.

Sokar Boat (Seker Boat) it was the Hennu, a bark mentioned in the topic of the dead. The vessel was designed with a high brow, terminating in the head of a horned animal, usually a gazelle or oryx. The Sokar Boat had three oars. in the center was a funerary chest with a cover surmounted by the head of a hawk. The chest stood upon a base with curving ends, and the entire structure rested upon a sledge with runners. The pyramid texts depict the Sokar Boat, and sanctuaries were erected for such vessels in Lower Egypt.

Soknoknonneus

He was a mysterious crocodile deity popular in the Faiyum region in the later eras of Egypt. A temple to soknoknonneus was reportedly erected in the faiyum but has now vanished. He was originally called Soknopaiou-Mesos and was revered as a form of sobek.

solar boat

They were crafts meant to convey the kings to paradise and to carry deities. Examples of such vessels were buried in great pits beside the pyramids. The god re’s bark, used in his daily travels, was also a solar boat. Such vessels became elegant symbols of Egypt’s cultic rituals.

solar cult it was the state religion of Egypt, which can be traced to predynastic periods (before 3,000 b.c.e.) and was adapted over the centuries to merge with new beliefs. re, the sun god, accompanied by horus, the sky god, constituted the basis of the cult, which emerged in heliopolis. Other Egyptian deities were also drawn into the solar religion: thoth, isis, hathor, and WADjET.In time osiris was linked to the cult as well. The rulers of the Fourth (2575-2465 b.c.e.) and Fifth (2465-2323 b.c.e.) Dynasties particularly revered the cult and erected many sun temples in that epoch. From the reign of ra’ djedef (2528-2520 b.c.e.) the rulers declared themselves “the Sons of Re,” and the solar disk, emblem of the sun, became the symbol of these pharaohs.

The social implications of the cult were evident in the pyramid texts, which date to the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. in them Re calls all Egyptian men and women to justice, equality, and the understanding that death awaits them all in time. Even in the New Kingdom Period (1550-1070 b.c.e.), the Ramessids bore names meaning “Re fashioned him.”

solar disk

A sacred symbol of Egypt, representing the sun and in some eras called the aten, this disk was normally depicted as resting on the Djet or Tjet tree of the god osiris. isis and nephthys are also portrayed in cultic symbols as saluting the solar disk, and baboons, representing the god thoth, were believed to praise the solar disk’s rising.

Soleb

A site in nubia (modern Sudan), in the territory of the third cataract of the Nile. amenhotep iii (r. 13911353 b.c.e.) erected a temple there, and Soleb served as the capital of Kush, or Nubia, during his reign. The temple was dedicated to the god amun but also presented Amenhotep III as a deified ruler.

Sonebi (fl. 20th century b.c.e.)

Aristocrat of the Twelfth Dynasty

He served in the reigns of amenemhet i (1991-1962 b.c.e.) and senwosret I (1971-1926 b.c.e.). Sonebi was a prince of the fourteenth nome, the son of ukhotep of meir. His tomb, located in Meir, contained cellars, menats (2), sistrums, and other mortuary symbols. The tomb, reflecting sonebi’s rank and office of provincial governor, contains elaborate paintings and reliefs, as well as hymns to HATHOR.

Sopdu (Sopdet)

He was an ancient Egyptian god and the star known to the Greeks as sirius, sothis, or the Dogstar, Alpha Canis Majoris. The appearance of Sopdu signaled the beginning of akhet, the season of inundation of the Nile. Sopdu was also a divinity of the eastern desert and the god of the four corners of the earth, with horus, set, and thoth. When associated with Horus, the god was “the sharp Horus.” The star was sometimes represented in a feminine form and then was associated with the goddess hathor. His consort was Sopdet.

Sopdu’s name meant “to prepare,” and he was represented by a zodiacal light on a tall cone. He probably was eastern in origin and was transformed into the husband of Sah (Orion). Sopdu was mentioned in the pyramid texts. The god was also depicted on an Abydos ivory tablet, owned by djer of the First Dynasty (2920-2770 B.C.E.).

Sosibius (fl. third century b.c.e.)

Courtier involved in murder and a deadly cabal

He served ptolemy iv philopator (r. 221-205 b.c.e.), and when that ruler died, sosibius and fellow courtiers, including one agathocles (2), murdered Queen arsinoe (3) to remove her influence. sosibius thus became the guardian of the heir, ptolemy v epiphanes, who was placed on the throne at the age of five. He remained guardian until he retired in 202. When the people of Alexandria, led by General tlepolemus, avenged the death of Arsinoe (3), sosibius may have been slain with his fellow conspirators.

Sostratus of Cnidus (fl. third century b.c.e.)

Greek architect who designed the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Pharos

He was asked to design the monument by ptolemy i soter (r. 304-284 b.c.e.), who knew of Sostratus’s reputation and achievements. sostratus was honored with a plaque on one of the tiers of the lighthouse of ALEXANDRiA,a Wonder of the World.

Sothic Cycle it was a method of measuring time in ancient Egypt, associated with the rising of sopdu (Sir-ius). For the Egyptian the solar year measured 365 days and six hours. These additional hours added up to a discrepancy of a quarter day per year, an error that was corrected after a period of 1,460 years, termed the Sothic cycle. such cycles had termination dates of 1317, 2773, 4323 b.c.e., etc. The synchronization of time was possible in the interims by calculating years from the cycle dates.

Sothic Rising

The term defining the star and goddess sopdet, who gave birth to the morning star and personified Sirius, or sopdu. The Sothic rising coincided with the start of the solar year once every 1,460 or 1,456 years. The time between such risings was called the Sothic Cycle. The actual accounts of the Sothic Risings in ancient Egyptian documents enabled scholars to designate dates for the dynasties and to establish chronologies.

soul bird

It was a human-headed bird, representing ba, or soul, that was placed on the shabti figures found in tombs in Egypt. The shabti was placed in the gravesite to perform any required labors in Amenti, the land beyond death. The soul birds appeared as part of the shabti figures in the Nineteenth Dynasty. The ba, or soul, was represented in various versions of the topic of the dead from earliest times.

soul houses

They were elaborate mortuary miniatures placed in the tombs of the Middle Kingdom Period (2040-1640 b.c.e.). Also called the house of the ka, these miniatures were models of Egyptian residences, some two-storied with double staircases. Made of pottery and sometimes highly detailed, the soul houses were placed in the forecourts of tombs as offerings to the kas of the deceased, the astral companions. They served as the ka’s residence in death.

Souls of Nekhen

The title given to the predynastic rulers of hierakonpolis, who were believed to have attained celestial status beyond the grave, the souls of Nekhen were guardians of upper Egypt, as their counterparts, the souls of pe, served as patrons of Lower Egypt in buto. The Souls of Nekhen were thought to accompany the pharaoh during certain commemorative ceremonies, such as the heb-sed, and were prominent at coronations, when priests donned special garb and stood as representatives of these archaic rulers.

The crowns of Egypt could not be presented to a pharaoh without permission by the souls of Nekhen and Pe. mortuary rituals were also conducted on their behalf and they had their own ritual centers in the capital. One such soul was depicted on a statue of amen-hotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.), dressed as an Egyptian wolf or wild dog. The Souls of Nekhen and the Souls of Pe were mentioned in the palermo stone.

Souls of Pe

The title of the predynastic rulers of Pe or buto, a site south of tanis, in the Delta, believed to have become celestial beings in the afterlife, they were the guardians of Lower Egypt, as the souls of nekhen protected Upper Egypt. The Souls of Pe were thought to greet each new pharaoh during coronation rituals and were called upon to guard the land in each new reign. mortuary rituals were conducted on their behalf, and the souls of Pe had their own cultic shrines in the capitals of Egypt. They were mentioned in the palermo stone and were always depicted with the heads of hawks.

speos

It was the Greek word for ancient Egyptian shrines dedicated to particular deities.

Speos Anubis

This was a shrine erected at deir el-bahri on the western shore of thebes to honor the deity of the dead. This mortuary god received daily offerings at the speos.

Speos Artemidos

This was the Greek name for the rock chapel dedicated to the goddess pakhet or Pakht at beni hasan. The chapel was erected by hatshepsut (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.) and tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) and refurbished by seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.),who inserted his own cartouche into the decorations. The speos had a portico with four pillars cut into the rock, along with narrow chambers and a deeper sanctuary. The shrine appears to have been erected on the site of a previous structure of the goddess’s cult. The Greeks associated Pakhet with their own Artemis, hence the name. The site is now called the Stable of Antar, named after a warrior poet of modern islam.

Speos of Hathor

This was the title of a shrine erected at deir el-bahri, on the western shore of the Nile in thebes. The goddess hathor was honored at this shrine, and only royal princesses could serve as priestesses in ceremonies. offerings made to Hathor during rituals included miniature cows, platters of blue and white faience, and strings of faience scarabs. Flowers and fruit were also dedicated to Hathor in elaborate services.

sphinx

It was the form of a recumbent lion with the head of a royal personage, appearing in Egypt in the old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.). Originally called hu, or “the hewn object,” the sphinx became Hun-Harmakhu, “the hewn Harmachis (Horemakhet).” This divine being was also addressed as “Horus on the Horizon” and as sheshep-ankh, “the living image” of the god Atum. Modern Egyptians herald the sphinx as Abu Hol, “the Father of Terror.”

The Great Sphinx, on the giza plateau, measures approximately 70 feet from base to crown and bears the face of khafre (r. 2520-2494 b.c.e.). Measuring some 150 feet in length, the Great sphinx is a crouching lion with outstretched paws and a human head, clad in the nemes, the striped head covering reserved for pharaohs in the early eras. The actual stone of the figure dates to 5000-7000 years ago geologically, according to some scientists, and may have been an original rock formation carved to resemble the sphinx form. The Great sphinx was also supposed to hold the repository of ancient Egyptian wisdom, including the lost topic of thoth. Modern repairs and excavations have revealed no such treasures.

The inventory stela, now in the Egyptian Museum in cairo, describes the construction of the Great sphinx. Another stela, erected between the paws of the sphinx by tuthmosis iv (r. 1401-1391 b.c.e.), gives an account of his act of clearing the area of sand and of restoring the sphinx itself. The stela, 11 feet, 10 inches tall and seven feet, two inches wide, was placed at the site to commemorate Tuthmosis IVs dream. He was on a hunting expedition on the plateau as a prince and rested beside the sphinx. To his amazement, he heard the figure complain about its state of disrepair. Tuthmosis IV was promised the throne of Egypt if he cleared away the sand and rubble, even though he was not the heir at the time. He fulfilled the command of the sphinx and became pharaoh.

Other noted sphinx figures include the Alabaster sphinx, said to weigh 80 tons and discovered in the ruins of the city of Memphis, the oldest capital of Egypt. The face on this particular sphinx is believed to be that of amenemhet ii (r. 1929-1892 b.c.e.).

The Sphinxes of tanis are unique versions of this form dating to the Twelfth Dynasty. They were created for amenemhet iii (r. 1844-1797 b.c.e.) out of black granite. Their faces are framed by the manes of lions rather than the striped nemes. Remarkably striking, these forms were unique to Tanis but were used by later pharaohs. hat-shepsut (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.) was depicted as a Tanis sphinx. smaller versions of the sphinx were used to form annexes between temples in thebes (modern luxor). In some instances these sphinxes were ram-headed, then called criosphinx. such figures lined the avenue between shrines in Thebes.

“Sponge-cake Shrine” An unusual bark receptacle erected by tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) at karnak, this religious monument was built alongside the white chapel of senwosret i (r. 1971-1926 b.c.e.) and the Alabaster Shrine of amenhotep i (r. 1525-1504 b.c.e.) and tuthmosis i (r. 1504-1492 b.c.e.) in that great temple site at Thebes. Tuthmosis Ill’s shrine was made of cal-cite and had reliefs depicting that pharaoh making offerings to the deity amun-Re. The modern name for the monument refers to the deterioration evident. The calcite blocks used in the original construction have become severely pitted, giving the structure the appearance of sponge cake.

stations of the gods

They were the shrines erected in Egypt’s major cities to provide resting places for the arks or barks of the various deities when they were paraded through the streets during festivals. Highly decorated, these stations provided spectacles for the participating worshipers.

At each station, the bearers of the god’s vehicle rested while the cultic priests purified and incensed the entire parade. oracles were also conducted at these stations. In the major cities of Egypt, the arks or barks of the ranking deities were carried through the streets from five to 10 times each month as part of the liturgical calendar and the cultic observances.

stela

This is the Greek word for a pillar or vertical tablet inscribed or decorated with reliefs. such monuments were called wadj or aha by the Egyptians and were used as mortuary or historical commemoratives. stelae were made of wood in the early eras, but as that material became scarce and the skills of the artisans increased, stones were used. They were normally rounded at one end, but a stela could be made in any style.

In the tombs, the mortuary stelae were placed in prominent positions. in most cases the stelae were incorporated into the false door of the tomb. others were freestanding pillars or tablets set into the tomb walls, listing the achievements of the inhabitant of the gravesite. stelae were used to designate boundaries, as in the city of ‘amarna, or to specify particular roles of temples and shrines. They have provided the world with detailed information about the historical periods of ancient Egypt.

Stela of Donation

This is a memorial tablet dating to the reign of ‘ahmose (1550-1525 b.c.e.) and concerning the honors bestowed upon Queen ‘ahmose-nefertari, his beloved consort. The stela announces that the queen has resumed her honorary role as the second prophet of amun, a prominent priestly role at Thebes. Instead, she was endowed with the title and estate of the god’s wife of amun. ‘Ahmose-Nefertari is depicted with Prince ‘ahmose-sipair, who possibly served as coregent with ‘Ahmose but died before he could inherit the throne. amenhotep i, the eventual heir, shared a mortuary cult with ‘Ahmose-Nefertari, and they were deified posthumously.

Step Pyramid

It was the tomb of djoser (r. 26302611 b.c.e.) erected in saqqara and called the first freestanding stone structure known on earth. Designed by imhotep, Djoser’s vizier and architect, the pyramid was conceived as a mastaba tomb, but six separate mastaba forms were placed one on top of another, diminishing in size to form a pyramid. in its final form, with six tiers, the step pyramid rose almost 200 feet on a base of nearly 500 feet from north to south and close to 400 feet from east to west. The nucleus of the structure was faced with Tureh limestone.

The original mastabas were 26 feet, each side facing a cardinal point measuring 207 feet. When completed, the sides of each tier were extended by 14 feet and faced a second time with limestone. other mastabas were formed above the original and enlarged to form the step pattern until the six layers were intact.

A great shaft was designed within the step pyramid, 23 feet square and descending 90 feet into the earth. The burial chamber at the bottom is encased in granite. A cylindrical granite plug sealed the room, and a hole at the northern end of the underground chamber allowed the body of Djoser to be lowered into place. The granite plug used to seal the chamber weighed three tons. The shaft was then sealed with rubble. other shafts, 11 in number,were designed for the tombs of Djoser’s royal family members. Adjoining subterranean passages and chambers were adorned with fine reliefs and with blue faience tiles designed to resemble the matted curtains of the royal residences at Memphis. Mazes were also incorporated into the design as a defense against tomb robbers.

The Step Pyramid, the first pyramidal monument ever erected in Egypt. Built at Saqqara for Djoser, the Step Pyramid was the creation of the priest official Imhotep.

The Step Pyramid stands as the centerpiece of a vast mortuary complex in saqqara, enclosed by a wall 33 feet high and more than a mile in length. The wall was made of limestone and contained 211 bastions and 14 doors, all carved to resemble the facade of the royal palace. The main entrance at the southeast corner leads to a hall 175 feet long, decorated with engaged columns. A vestibule with eight columns connects to this hall. Another court held the sacred stones carried by the pharaohs in the heb-sed rituals and three shrines.

A special chamber was designed to honor the patroness of Lower Egypt, with statues of cobras and appropriate reliefs. That chamber led to a chapel, which contained a false tomb, complete with a shaft, glazed tiles, and inscriptions, followed by another court, all called the House of the south, containing proto-Doric columns, engaged. The House of the North, with similar design, had engaged papyrus columns. A room of special interest incorporated into the complex was the serdab, the slitted chamber which contained a statue of Djoser, positioned so that he could witness the mortuary rituals being conducted in his honor by the priests of the royal cult and also view the rising of the North star. The statue was the first life-sized representation of a human being in Egypt.

Two other buildings represented the upper and Lower Kingdoms in the complex. Some 30,000 vases, made of alabaster, granite, diorite, and other stones, were found on the site as well. saqqara was a miniature city of 400 rooms, galleries, and halls, where priests and custodians served for decades. Modern excavations are unearthing new chambers, monuments, and tombs. During the Saite Dynasty, the Twenty Sixth (664-525 b.c.e.), a gallery was excavated in the Great south court and revealed chambers.

steps

They were an ancient Egyptian symbol representing the staircase of ascension and the throne of the god osiris. As amulets, the steps were worn by the living and placed with the mummified remains of the deceased to assure their resurrection and entry into Osiris’s eternal domain.

Strabo (d. 23 c.e.)

Noted Greek geographer and historian who visited Egypt

He was born at Pontus on the Black Sea around 64 b.c.e. and became a scholar. strabo visited Egypt and sailed up the Nile. He also depended upon Eratosthenes of Alexandria for information about the Nile Valley. Strabo is considered a major source for information concerning the ancient world. His Geographical Sketches appeared in 17 volumes. His Historical Sketches was known to have been in numerous volumes, but there are no extant parts of the work. He died in 23 c.e.

Strato (fl. third century b.c.e.)

Greek scientist and royal tutor

He arrived in Alexandria in the reign of ptolemy i soter (304-284 b.c.e.) to tutor the heir to the Egyptian throne, ptolemy ii philadelphus. Strato was considered the leading physicist at the Athens Lyceum and was revered. He, in turn, invited philetas of cos and zenodotus of Eph-esus to Alexandria, adding to that city’s reputation as an academic center.

sun boat

It was a divine vehicle depicted in an early cosmogonic myth, the mode by which the god re, or the sun itself, traveled through the sky into the realms of night. The sun deity, whether personified as Re or in his original form, was thought to travel across the sky on this vessel. sometimes the boat or bark was shown as a double raft. on his journey, Re was accompanied by the circumpolar stars or by his own double. sometimes he rowed the boat himself, sometimes he moved by magic. Heka, magic, accompanied the sun in most myths.

The ennead of Heliopolis was composed of gods who also accompanied the sun in its daily journey. The souls of nekhen and the souls of pe were mentioned in some myths as riding in the vessel daily. in some early depictions, the boat was a double serpent, its two heads forming the prow and the bow. The sun boat had many adventures during the day, and at night it faced all the terrors of the darkness, when the dead rose up to the vessel through the waters. When the sun was associated with the cult of Re, the boats were given specific names.

Sun’s eye

It was a symbol used in amulets and resembling the eye of re. This insignia denoted all things good and beautiful on the Nile. All life emanated from the sun, and this symbol, part of the many solar cults, honored that element of existence.

Sun’s well

This was the name given to a pool in the sacred precincts of heliopolis (originally the city of On and now a suburb of modern cairo). Associated with the deity re, the sun’s well was viewed as a site of the original creation. The god Re rose as a lotus of the sun’s well.

Suppiluliumas I (d. c. 1325 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the Hittites and a threat to Egypt

He ruled the hittite Empire in the reigns of amenhotep iii (1391-1353 b.c.e.) and akhenaten (1353-1335 b.c.e.). Suppiluliumas I fought Egypt’s allies, the mitan-nis, in Syria. He also destroyed the city-state of ka-desh, taking the royal family of that city and its court as prisoners. He exchanged gifts with Amenhotep iii and Akhenaten, growing powerful during their reigns. sup-piluliumas’s son, Prince zannanza, was sent to Egypt to become the consort of Queen ankhesenamon, the widow of tut’ankhamun (r. 1333-1323 b.c.e.), but he was slain at the borders. The Hittites began a series of reprisal attacks as a result, and suppiluliumas i died of a plague brought to his capital by Egyptian prisoners of war.

Sutekh

A very ancient deity of Egypt, called “the Lord of Egypt.” His cult dates to the First Dynasty (2920-2770 b.c.e.), perhaps earlier, at ombos, near nagada. Sutekh was originally depicted as a donkey-like creature but evolved over the decades into a beautiful recumbent canine. Considered a form of the god set, Sutekh was popular with ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.), who beseeched the god for good weather during the visit of a hittite delegation to Egypt.

Sweet Water Canal

A manmade waterway started probably the Middle Kingdom Period (2040-1640 b.c.e.). The canal linked the Nile River at bubastis to the wadi timulat and the bitter lakes. During the reign of necho i, the Sweet Water Canal led eventually to the Red Sea.

sycamore

This was a sacred tree of Egypt, Ficus sycomonus, viewed as a divine natural element in all eras. The fig of the tree was relished and its shade was prized. The souls of the dead also enjoyed the benefits of the sycamore, coming to roost in the tree as birds. Twin sycamores stood on the horizon of eternity, guarding the sun. The mortuary complex of montuhotep ii (r. 2061-2010 b.c.e.) at deir el-bahri, on the western shore of the Nile in Thebes, was designed with a sycamore grove. The sycamore grew at the edge of the desert near Memphis in the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 b.c.e.) and was venerated as an abode of the goddess hathor, “the Lady of the Sycamore.” Some religious texts indicate a legend or myth had developed concerning the tree. The tree was also involved in the cults of re, mut, and isis.

Syrian Wars

This is the name given to a series of confrontations and actual battles conducted by the ptolemaic rulers and the kings of the Seleucid Empire. The first war involved ptolemy ii philadelphus (r. 285-246 b.c.e.), who conquered phoenicia, Anatolia, and the cyclades, all Seleucid territories. The war took place between 274 and 271 b.c.e.

Ptolemy ii lost Phoenicia and Anatolia to the seleu-cid king antiochus ii (theos) in a war that was conducted from 260-253 b.c.e. From 245-241 b.c.e., Ptolemy II saw Egypt’s sea power destroyed, and the seleucids suffered losses as well.

ptolemy iv philopator (r. 221-205 b.c.e.) was involved in another campaign in 219-216 b.c.e. and won

the Battle of raphia, capturing southern Syria and Palestine (Coele Syria). In 202-200 b.c.e., the Seleucids once again fought to regain Palestine, confronting ptolemy v epiphanes (r. 205-180 b.c.e.).

Twentieth Dynasty

He served ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) as vizier. Ta’a is mentioned in the records of the royal jubilee of the reign. His successors would rebel against Ramesses iii and be captured at athribis, but he was a loyal servant of the pharaoh. He sailed north after gathering religious articles from Thebes, taking them to per-ramesses, the capital at the time. He visited Egyptian cities while en route. During the strike of tomb workers at deir el-medina, Ta’a distributed rations to the people in order to avert disaster. His courage and wisdom delayed the unrest that struck Thebes.

Ta’apenes (fl. 10th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-first Dynasty

She was the consort of psusennes i (r. 1040-992 b.c.e.), a lower-ranked queen, as mutnodjmet (2) was the Great Wife. Some records indicate that Ta’apenes’s sister was sent to jerusalem to serve at the court there.

Tabiry (fl. eighth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty

She was the consort of piankhi (r. 750-712 b.c.e.) and the daughter of the Nubian ruler alara and Queen Kasaga. Tabiry was possibly the mother of shabaka and shepenwepet (2). It is not known if Tabiry accompanied Piankhi on his military campaigns in Egypt. Her daughter, shepenwepet (2), became a god’s wife of amun, or Divine Adoratrice of Amun, during Piankhi’s reign.

Tadukhipa (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Eighteenth Dynasty, a Mitanni princess She was a consort of amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) and a mitanni royal princess, given to Amen-hotep iii to cement the ties between Egypt and her homeland. Tadukhipa was also a niece of the mitanni princess Khirgipa, who had entered Amenhotep Ill’s harem earlier. Tadukhipa arrived shortly before Amen-hotep iii died or perhaps soon after. she is mentioned in a letter written by Queen tiye (1), Amenhotep Ill’s widow, as having married akhenaten. As a result, some scholars believe that Tadukhipa was Queen kiya of Akhenaten’s court.

Taharqa (Khure’ nefertem, Tarku, Tirhaka) (d. 664 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty He reigned from 690 b.c.e. until forced to abandon Egypt. He was the son of piankhi and the cousin of shebitku, whom he succeeded. His mother, abar, came from nubia (modern Sudan) to visit and to bless his marriage to Queen amun-dyek’het. They had two sons, Nesishutef-nut, who was made the second prophet of Amun, and ushanahuru, who was ill-fated. Taharqa’s daughter, amenirdis (2), was adopted by shepenwepet (2) and installed as a god’s wife of amun at thebes.

In 674 b.c.e., Taharqa met the Assyrian king essarhaddon and his army at Ashkelon, defeating the enemy and raising a stela to celebrate the victory. He also built extensively, making additions to the temples of amun and montu at karnak and to medinet habu and Memphis. One of his structures at Karnak was erected between a sacred lake and the outer wall. He built two colossal uraei at Luxor as well and a small shrine of Amun at the third cataract of the Nile.

In 680 b.c.e., Essarhaddon once again attacked Egypt and took the capital of Memphis and the royal court. Taharqa fled south, leaving Queen Amun-dyek’het and Prince Ushanahuru to face the enemy. They were taken prisoner by Essarhaddon and sent to Nineveh, Assyria, as slaves. Two years later, Taharqa marched with an army to retake Egypt, and Essarhaddon died before they met. Taharqa massacred the Assyrian garrison in Egypt when he returned. assurbanipal, Essarhaddon’s successor, defeated Taharqa. tanutamun, Taharqa’s cousin, was installed as coregent and successor and Taharqa returned to Nubia. He was buried at Nuri in Nubia. His pyramidal tomb was small but designed with three chambers.

Tait An Egyptian goddess who served as the patroness of the city of akhmin and was associated with the cults of isis and osiris, Tait was the guardian of linen, was used in the mortuary rituals, and was depicted as a beautiful woman carrying a chest of linen. When associated with the cults of Osiris and Isis, she was called Isis-Tait. Tait aided isis in wrapping the body of the god osiris after he was slain by set.

Takelot I (Userma’atre’setepenamun) (d. c. 883 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the Twenty-second Dynasty

He reigned from 909 b.c.e. until his death. The son of osorkon i and Queen karomana (2) or Queen tased-konsu, Takelot I was not the original heir. A brother, shoshenq ii, died before he could inherit the throne, and Takelot I became regent. He married Queen kapes, the mother of osorkon ii. Thebes revolted during Takelot I’s reign, and he sent his brother, iuwelot, there to become the high priest of Amun, followed by smendes iii. He left no monuments and was succeeded by osorkon ii. Takelot I was interred in tanis in a gold coffin and in a sarcophagus usurped from the Twelfth Dynasty and placed in the tomb of smendes.

Takelot II (Hedjkheperre’setepenre) (d. 835 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the Twenty-second Dynasty

He reigned from 860 b.c.e. until his death. Takelot II was the son of osorkon ii and Queen karomana (4) but not the original heir. A brother, shoshenq, did not live long enough to inherit the throne. nimlot, the high priest of Thebes, was his half brother. Takelot ii married Nimlot’s daughter, karomana (5) Merymut, who was the mother of osorkon iii.

During his reign, Takelot faced a Theban revolt led by harsiese. He sent his son, Prince osorkon, to thebes to put down the rebellion that raged for a decade. A truce was finally drawn up but a second revolt began soon after. The rebellion was recorded on the walls of karnak at Thebes. Takelot was buried in the tanis tomb of his father.

Takelot III (fl. c. 749 b.c.e.)

Ruler of the obscure Twenty-third Dynasty at Leontopolis

The dates of his reign are unknown. He was the son of osorkon iii and Queen karaotjet so probably inherited the throne c. 749 b.c.e. In that time of turmoil, Takelot III was named to the throne of shoshenq v at tanis and also held sway over herakleopolis. He ruled only two years, however, and during that time appointed his sister shepenwepet (1) the god’s wife of amun at Thebes. rudamon, his brother, succeeded him. Takelot Ill’s family was buried at deir el-bahri in Thebes, interred on a terrace of hatshepsut’s shrine. His tomb has not been discovered.

Takhat (1) (fl. 13th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Nineteenth Dynasty and the mother of a usurper She was probably a lesser-ranked consort of merenptah (r. 1224-1214 b.c.e.). Takhat was also the mother of amenmesses, who usurped the throne from seti ii (r. 1214-1204 b.c.e.). She was probably a daughter of ramesses ii. Takhat was buried in the tomb of Amenmesses. Some records list her as a consort of seti ii and as the mother of Amenmesses and seti-Merenptah. she was reportedly depicted on a statue of Seti II at karnak.