Introduction

The discovery and reporting of a crime will in most cases lead to the start of an investigation by police, who may often rely on the specialized skills of the crime scene investigator to locate, evaluate and record the physical evidence left at, or removed from, the scene. Such investigations are reliant upon the physical transfer of material, whether it be obvious to the eye or otherwise. It is the successful collection of this evidence that often assists the police in the prosecution of an offender before the court. It has been said that ‘Few forms of evidence can permit the unquestionable identification of an individual . . . and only digital patterns [fingerprints] possess all the necessary qualities for identification’. It is the forensic use of these fingerprints that will now be addressed.

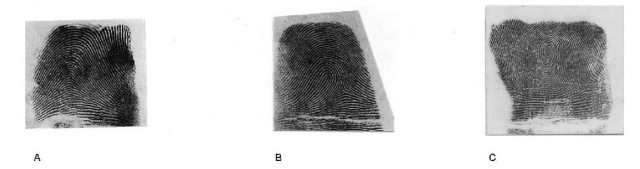

The skin on the inner surface of the hands and soles of the feet is different from skin on other areas of the body: it comprises numerous ridges, which form patterns, particularly on the tips of the fingers and thumbs. Examples of three primary pattern types, arch, loop and whorl, can be seen in Fig. 1.

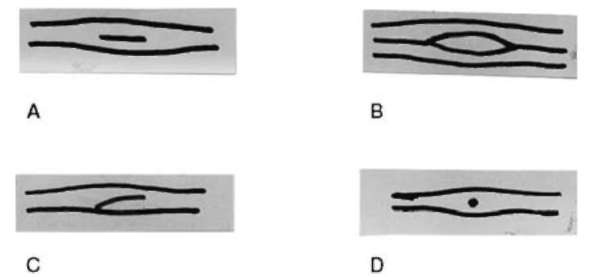

The ridges are not continuous in their flow, in that they randomly end or bifurcate. An example of a ridge ending and a bifurcation can be seen in Fig. 2. The ridge endings and bifurcations are often referred to as ‘characteristics’, ‘Galton detail’ (named after one of the early and influential pioneers of the science), ‘points’ or ‘minutiae’. The characteristics often combine to create various configurations and these have been assigned names, as can be seen in the examples provided in Fig. 3. The ‘dot’ (Fig. 3D) is often the subject of debate as to whether it is uniquely a characteristic, such as the ridge ending or bifurcation, or a combination of two ridge endings; however, such debate is of academic value only. The ridges themselves provide us with the ability to grip and hold on, and the skin in this context is referred to as friction ridge skin.

On closer examination of the ridges it can be seen there are small sweat pores on their upper surface area and no hairs are present. The perspiration, which is exuded through the sweat pores, is primarily water; on reaching the surface it will be deposited along the tops of the ridges. Additional matter or contaminates may also be present on the ridges, collected from oily regions of the body or some other foreign source, such as food, dirt, grease or blood. When an area of friction ridge skin comes into contact with a surface, a deposit of the perspiration or contaminate may well be left on that surface, leaving an impression of the detail unique to the individual.

A friction ridge skin impression is generally difficult to visualize and is often referred to as a latent deposit. The impression may, however, be visible if it has been deposited in dirt, blood or some other easily seen medium. There are some acids contained in the perspiration which may cause the impression to become ‘etched’ into some soft metals, while friction ridges may also be impressed into soft media such as putty.

Figure 2 (A) Ridge ending. (B) Bifurcation.

Figure 3 Configurations: (A) island or short ridge; (B) lake or enclosure; (C) spur; (D) dot.

Examining the Crime Scene

The crime scene will be examined by a scene of crime officer or a fingerprint technician. In either case it will be the responsibility of that person to conduct an examination of the scene in an effort to locate and develop fingerprints that may have been left by the person who committed the offense. It has been said that a scientific methodology must be applied to the crime scene examination, as follows:

1. Make observations.

2. Arrive at a hypothesis.

3. Test the hypothesis against the physical evidence observed until it cannot be refuted.

Surprisingly, many examiners do completely the opposite when they undertake a crime scene examination.

The examination will generally be started at the point at which entry was gained, if this can be determined. Consideration will be given to all surfaces or objects that have been touched or handled during the commission of the crime, including the point of egress, should this be different than the point of entry. For this examination to be thorough, it will be necessary to speak with either the investigating police or the victim of the crime. Should the crime scene officer or fingerprint technician have the opportunity of speaking with witnesses, vital information regarding items from or areas of the scene may be obtained. The opportunity of speaking with witnesses is not often afforded to the crime scene officer or fingerprint technician and the investigating police are very much relied upon, along with the victim, for the provision of information that may assist in the examination.

Figure 1 Fingerprint patterns: (A) arch; (B) loop; (C) whorl.

At serious crime scenes a more extensive examination will generally be undertaken. This may include walls, bench tops or other large surfaces or items that may have been touched by the offender(s) during the commission of the offense. The use of some of the techniques available for the examination of these surfaces or items may in itself be destructive; therefore, the extent of their use must be considered with respect to the seriousness of the crime being investigated.

Any visible friction ridge impressions should be recorded photographically. Generally, it is not necessary to undertake any other means of improving the visualization of such impressions but a number of high-intensity forensic light sources are commercially available and may be taken to the crime scene to assist in examining the scene for fingerprints in the initial stages. These light sources are not generally carried by the examining officer when attending routine crime scenes, but are regularly used at serious crime scenes. When using them, it may be necessary to darken the scene by covering the windows, etc., or conducting the examination at night. An examination of a crime scene using a forensic light source may reveal fingermarks where the presence of some medium on the friction ridges responds to a particular wavelength in the light spectrum, enabling the mark to be visualized.

Routine examinations of latent fingermarks may be initiated with the simple use of a light, such as a torch, played over a surface, followed by the application of an adhesive development powder to those surfaces, considered suitable for this process. Generally, adhesive powders are only appropriate for the examination of smooth, nonporous surfaces, such as glass and painted wood or metal. The selection of powder, white, gray or black, depends upon the surface color, keeping in mind that the objective is to improve overall contrast of any impression located.

The powders are generally applied to the surfaces being examined with a light brushing technique. The brushes vary from soft squirrel hair to glass fiber. Magnetic powders are also available and are applied with a magnetic ‘wand’. Once the latent friction ridge skin impression is visualized or developed, as is the term often used, it will be either photographed or lifted, using adhesive tape. In either case, the impression should be photographed in situ to corroborate its location, should this be necessary at a later time. A small label bearing a sizing graph and a unique identifier should be affixed adjacent to the impression for later printing of photographs at the correct and desired ratio. Should it be decided to lift the impression, this is then placed on to a suitable backing card, either black or white, depending on powder color, or on to a clear plastic sheet.

Many objects, particularly some types of plastics, and porous surfaces such as paper, are better examined using laboratory-based processes. Any such items located at the scene should be collected and sent to the laboratory for examination. For permanent fixtures at the scene not suitable for powder development, some laboratory-based examination processes can, with appropriate preparation, be used. Some of these techniques are addressed in the next section. It must be remembered that, in using these processes at the crime scene, issues relating to health and safety must be considered and jurisdictional regulations must be adhered to. In deciding which processes to use, sequential examination procedures must be observed when attempting to visualize friction ridge skin impressions, whether at the scene or in the laboratory.

Before departing from the crime scene, it will be necessary for the crime scene officer, with the assistance of investigating police, to arrange for inked finger and palm prints to be obtained from all persons who may have had legitimate access to the scene or items to be examined. These inked impressions are generally referred to as elimination prints and should not be confused, as is often the case, with inked impressions that may be obtained from suspects for the purpose of eliminating them from police inquiries. Such impressions are, in reality, obtained for the purpose of implicating rather than eliminating.

Laboratory Examinations

The most common methods of examining porous surfaces, such as paper, use chemicals such as DFO (l,8-diaza-9-fluorenone) and ninhydrin. These chemicals react with amino acid groups that are present in perspiration. If DFOand ninhydrin are both to be used, it is necessary to use DFO first for best results. Friction ridge skin impressions are generally difficult to visualize after processing with DFO; however, using a suitable high-intensity light source, in combination with appropriate filters, developed impressions will be photoluminescent, enabling photographic recording. Processing with ninhydrin will generally enable any impressions present to be visualized, in ambient light, as a purple image. Once again, these can be recorded photographically.

If it is known that the paper items to be examined have been subjected to wetting then neither DFOnor ninhydrin is suitable. The reason for this is that amino acids deposited into the porous surface, being water-soluble, will be diffused. In such cases, however, a physical developer process can be used. This process relies on nonsoluble components of the friction ridge skin deposit, which may have been collected through touching other areas of the body or foreign surface, still being present on the surface touched. This process is more labor-intensive than methods using DFO or ninhydrin, but is quite effective. The impressions which may develop can be seen as very dark gray images and are easily visualized on lighter colored papers.

Items such as plastic, foil, firearms and knives can be processed using cyanoacrylate esters, commonly known as superglue. The items to be examined are placed into a closed chamber and a small amount of superglue is added. Heating the superglue helps it to fume. The glue will polymerize on to any fingerprint deposit which may be present on a given surface, appearing white and generally stable. Should the surface being examined be light in color, it will be necessary to enhance the developed impression with the use of dyes, stains or even powder. Once stained or dyed, superglue-developed impressions, like DFO, can then be visualized with the use of a high-intensity light source and appropriate filter, and then recorded photographically.

Evidence Evaluation

At the completion of the examination undertaken by the scenes of crime officer or fingerprint technician, the resulting adhesive fingerprint lifts or photographs will be forwarded to a fingerprint specialist. This specialist will examine the impressions submitted and conduct comparisons with known persons or search existing records in an effort to establish a match.

On receiving the evidence, the fingerprint specialist will undertake an evaluation of the quality of the impressions submitted. While a cursory evaluation is made at the crime scene, it is generally more definitive in an office environment with the appropriate lighting and equipment. Should it be determined that there is a significant lack of quality and quantity in the friction ridge skin impression, it may well be deemed, in the opinion of the specialist, to be of no value for any meaningful comparison. It is extremely important, however, that the evidence be retained with the case file for record and presentation, should full disclosure of evidence be required.

The remainder of the impressions would then be subject to comparison with known ‘inked’ finger and palm impressions. These inked impressions are obtained by placing the desired area of friction ridge skin on to black printer’s ink and then placing the inked skin on to suitable white paper. Usually, this would be a blank fingerprint form.

Identification Methodology

The premises

Fingerprint identification relies on the premise that detail contained in the friction ridges is unique and unchanging. The premises or fundamental principles of fingerprint identification are:

• Friction ridges develop on the fetus in their definitive form before birth.

• Friction ridges are persistent throughout life except for permanent scarring.

• Friction ridge patterns and the detail in small areas of friction ridges are unique and never repeated.

• Overall friction ridge patterns vary within limits which allow for classification.

The fourth premise is not strictly relevant to individualization, as classification only assists in narrowing the search by placing the fingerprints into organized groups.

The analysis

In analysing the friction ridge skin impression, the fingerprint specialist will consider all levels of detail available. This may simply be through consideration of pattern type, should this be obvious in the impression located at the crime scene. An example of this would be where an arch pattern, being the crime scene impression, is compared with known impressions, none of which can be seen to be arches, in which case the comparison may well be concluded at this time. This pattern evaluation may be referred to as first level detail and can often be undertaken with little use of a magnifying glass.

Should pattern types be consistent, or not be entirely obvious, which may generally be the case, it will then be necessary to commence examination of the ridge endings and bifurcations in an effort to determine whether the impressions were made by one and the same person. These ridge endings and bifurcations, or ‘traditional’ characteristics may be referred to as second level detail. Often this is sufficient, and historically, this is the only detail contained in the impressions that would generally be used.

Establishing identity with ‘traditional’characteristics

In determining whether two friction ridge skin impressions have been made by one and the same person, it will be necessary to locate sufficient ridge endings and bifurcations in true relative position and coincidental sequence. To achieve this, an examination of one of the impressions, generally that recovered from the crime scene, will be initiated. One, or perhaps two, characteristics may be observed and compared with characteristics appearing in the second impression, which would usually be the inked impression. Once such characteristics are located to the satisfaction of the examiner, a further examination of the first impression will be made in an effort to locate any additional characteristic. Again, the second impression will be examined to locate that characteristics. Having done this, the examiner will insure the characteristics observed are in the correct sequence, which means that each of the characteristics must be separated by the same number of intervening ridges. In addition, their position relative to each other must be considered.

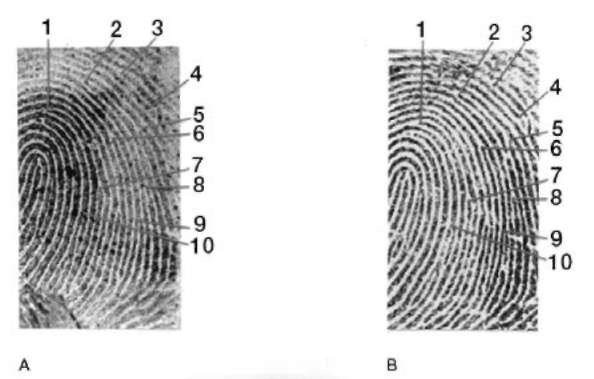

An example of the process can be seen in Fig. 4.In the two impressions shown in the figure, it can be seen that the marked characteristics are in relative position with one another. It can also be seen that the number of intervening ridges between points, for example l and 2, are the same in each impression -five intervening ridges in this case. Likewise, there are three intervening ridges between points 2 and 3. This process is continued throughout an examination until the examiner is either satisfied that an identification has been established, or that the impressions are not identical.

As an exercise, continue counting the intervening ridges between the marked points. The following is a selection against which you may compare your own findings:points 4 and 6 = five intervening ridges; points 6 and 9 = nil intervening ridges (trace the ridge from point 6 and you will arrive at point 9); points 10 and 8 = eight intervening ridges.

Numeric standards

As stated, fingerprint specialists have historically relied on the ridge endings and bifurcations for individualizing friction ridge skin impressions. Used in the manner discussed, this has resulted in the creation of numeric standards; that is to say, standards were set establishing a predetermined number of characteristics to be present, in relative position and sequence, before a fingerprint identification could be positively established for court presentation. These predeter-mined numeric standards differed throughout the world and have shown variations from 7 to 16. Each country had their own reason for their preferred standard, although many were based on statistical models that demonstrated the probability of no two people having the same fingerprint.

Figure 4 Friction ridge skin impressions: (A) crime scene; (B) inked. See text for discussion.

In l973, the International Association for Identification (IAI) met for their annual conference in Jackson, Wyoming, USA. A statement declaring no valid basis exists at this time for requiring that a predetermined minimum of friction ridge characteristics must be present in two impressions in order to establish positive identification,was subsequently adopted by all North American fingerprint identification examiners. This began a philosophy whereby an opinion of identification was not based on the number of characteristics present in two impressions.

New South Wales Police, in Australia, followed this direction in the early 1980s and, in doing so, broke away from the national standard, which was 12. The Australian Federal Police and the Northern Territory Police (Australia) also soon adopted a nonnumeric philosophy. In 1998, it was agreed that the national standard in Australia be accepted as nonnumeric; however, state jurisdictions are at liberty to maintain ‘office policy’ regarding minimum standards.

The United Kingdom maintains a numeric standard of 16 friction ridge skin characteristics before an identification can be presented at court, in routine circumstances; this is considered by many to be extremely conservative. This standard was challenged in a report prepared in 1989, which, however, was only released to a meeting in Ne’urim, Israel, in June 1995. The report was soon published in Fingerprint Whorld. The following resolution was agreed upon and unanimously approved by members at that meeting:

No scientific basis exists for requiring that a predetermined minimum number of friction ridge features must be present in two impressions in order to establish positive identification

Note the significant difference in the resolution, ‘no scientific basis exists compared with the IAI declaration, ‘no validbasis exists

The detail contained on and along the friction ridges, such as the sweat pores and ridge edges, are as unique to the individual as are the combination of ridge endings and bifurcations and may be used to support a fingerprint identification. This detail may be referred to as third level detail with its uniqueness soundly based in science. Third level detail is being increasingly accepted and used by fingerprint specialists rather than simply relying on a predetermined number of bifurcations and ridge endings. The scientific application of all the unique detail contained in the friction ridge skin is now being encompassed in a form of study being referred to more commonly as forensic ridgeology.

Ridgeology

Structure of friction ridge skin

To assist in understanding ridgeology, a description of the structure of friction ridge skin may be a good point at which to begin. This skin comprises two primary layers: the inner, or dermal, layer; and the outer, or epidermal, layer. Within the epidermal layer are five sublayers, the innermost layer being the basal. This layer connects to papillae pegs, which are visualized on the outer surface of the dermis. The basal layer generates cells that migrate to the surface of the skin. This migration, among other functions, enables the persistence of the detail visible in the friction ridges. From within the dermal layer, sweat ducts, from the eccrine gland, twist their way to the tops of the friction ridges, where small sweat pores may be seen.

The friction ridges themselves are constructed of ridge units, which may vary in size, shape and alignment, and ‘are subjected to differential growth factors, while fusing into rows and growing’. The ridges are three-dimensional, creating a uniqueness in the formation of the friction ridges, even in a very small area. Random forces, which result in differential growth, also affect the location of the sweat pore openings within a ridge unit. The detail associated with the sweat pores and the minute detail located on the ridge edges is significantly smaller than the traditional characteristics. It is however the minute detail and differential growth, which determines the position of the ridge endings and bifurcations, and overall ridge shape.

Poroscopy

Poroscopy is the method of establishing identity by a comparison of the sweat pores along the friction ridges; it was extensively studied by the French crimi-nologist, Edmond Locard, who found that sweat pores varied in size from 88 to 220 um. Locard demonstrated the value of poroscopy in the criminal trial of Boudet and Simonin in 1912, in which he marked up some 901 separate sweat pores and more than 2000 in a palm print recovered from the crime scene. Other such cases involving much lower numbers of sweat pores have been documented in more recent times.

Edgeoscopy

The term edgeoscopy surfaced in an article which appeared in Finger Print andldentification Magazine in 1962. The author suggested the use of ridge edges in conjunction with other friction ridge detail, which may be present, and assigned names to seven common edge characteristics, which included convex, concave, peak, pocket and angle.

Additional friction ridge skin detail

Further detail that may be utilized by the fingerprint examiner includes scarring, usually of a permanent nature, and flexion creases. In examining the palm area of the hands, the predominant flexion creases can be seen to be the point where the skin folds when you start to make a fist of your hand. The persistence of these creases was demonstrated by Sir William Herschel who compared two separate impressions of his own left hand taken 30 years apart.

Two murder trials in which flexion crease identifications were made have been conducted in North America.

Permanent scarring is created by injuries which may be inflicted upon the inner extremities of the epidermis, effectively damaging the dermal papillae. Once such a scar is created, it too becomes a permanent feature of the particular area of friction ridge skin. This permanence allows for such a scar to be used in the identification process when it appears in the two impressions being compared.

Fingerprints and Genetics

The friction ridge detail appearing on the palmar and plantar surfaces of identical, or monozygotic, twins will be as different and varied as will be encountered in each of us. It must be remembered that it is the detail located within and along the ridges that enables us to individualize areas of friction ridge skin. The pattern the ridges form, however, may very well be influenced by genetics. A number of publications have resulted from the study of the development of friction ridge skin. These studies were lengthy, so no attempt to disseminate their contents will be made in this discussion; however, a brief and very simplified account of their outcome is provided.

In the development of a human fetus, volar pads form and become evident around the sixth week. The placement of the volar pads conform to a morphological plan, and the placement and shape of these pads, which are raised areas on the hand, may influence the direction of the friction ridge flow, which in turn creates the particular pattern types that may be seen. Examples of this, it is believed, would be high cent-red pads, creating whorls, while intermediate pads with a trend are believed to form loops. While genetics may influence the pattern formation and general flow of the ridges, the location of ridge endings, bifurcations and other detail contained within each ridge is the result of differential growth at the developmental stage.

Conclusion

Fingerprints have been used for personal identification for many years, but not as much as they have throughout the twentieth century. It has been scientifically established that no two individuals have the same friction ridge skin detail, nor will one small area of this skin be duplicated on the same individual. This fact will not alter, nor therefore, will the importance of the fingerprint science and the role it plays in the criminal investigation process.