Emergence of the Concept

The concept of ‘designer drugs’ gained attention in the 1980s as a new expression for describing a number of recent arrivals among the psychoactive substances on the illegal drug markets. When introduced for intoxicating purposes, the substances in many cases escaped formal drug control, such as the Controlled Substances Act (US), the Misuse of Drugs Act (UK) or the Narcotics Control Act (Sweden); nor were they regulated under the United Nations International Drug Conventions (Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961; Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971). Thus, they were rapidly perceived by public authorities to constitute a challenge to traditional drug control.

The concept of designer drugs is generally attributed to Dr Gary L. Henderson of the University of California at Davis, who introduced the concept to describe new, untested, legal synthetic drugs mimicking the effects of illicit narcotics, hallucinogens, stimulants and depressants. The concept has, however, no established scientific or codified judicial definition. Instead, several definitions have been advanced: most converge on the following criteria, stating that designer drugs are:

1. psychoactive substances;

2. synthesized from readily available precursor chemicals;

3. marketed under attractive ‘trade marks’ (fantasy names);

4. not subjected to legal control as narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances, at least not at the time of their introduction on the nonmedical drug market.

Sometimes the following criteria are added:

5. being produced mainly or exclusively in clandestine laboratories;

6. having little or no established medical use.

In common parlance, a designer drug can be said to be a synthetic psychoactive substance having pharmaco-logic effects similar to controlled substances and initially remaining outside traditional drug control.

Sometimes, these drugs are referred to as analogs, analog drugs or homologs, to stress the analogy or homology of their pharmacologic properties (and chemical structure) to well-known controlled substances.

In media reporting, the concept also has a connotation of novelty: the drugs are seen as modern creations in the same sense as designer clothes in fashion.

Some designer drugs have nevertheless been known for decades: the process for synthesizing 3,4-methy-lenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) was patented in 1914.

The demarcation of the substances regarded as designer drugs is not universally accepted. Sometimes ‘old timers’, such as methamphetamine (widely abused in Japan in the 1950s), are included. The concept is fluid and dynamic, mirroring a continuous search for new psychoactive substances. The pioneer in this field is the American pharmacologist and chemist Alexander Shulgin (b. 1925), who for decades has been synthesizing and investigating the effects of hundreds of such substances.

Some designer drugs have also been studied experimentally in cult-like settings in religiously flavored attempts to experience altered states of human consciousness.

Issues of Forensic Interest

Designer drugs raise at least four issues of forensic interest:

1. Determination of the chemical composition of new substances on the illegal drug market, such as when ‘Hog’ in 1968 was shown to be phencyclidine (PCP).

2. Problems of detecting very low concentrations (p.p.b. range) of a substance in body fluids in cases of severe intoxication or fatal poisoning. Sometimes the health hazard may come from impurities, such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in the synthesis of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-4-piperidyl propionate (MPPP) as a heroin substitute resulting in severe parkin-sonism (the worst cases known as ‘frozen addicts’). The drugs have also be used secretly to intoxicate or sedate a person for aims of sexual abuse or robbery. The detection problem is aggravated by the fact that new substances may not be fully investigated in respect of metabolites and routine methods of detection.

3. Determination of the particular substance used in a case of individual drug intoxication, especially when police diagnostic methods (such as the American drug recognition expert (DRE) wayside procedures) are used, as some designer drugs may not be controlled substances within the scope of domestic drug legislation.

4. Strategies to be used for controlling new drugs, e.g. drug scheduling, when a large number of new and unknown substances appear on the market. The number of designer drugs that can be produced in clandestine laboratories has been estimated to be from 1000 upwards, depending on the competence and resources of the chemist.

Major Types of Designer Drugs

Designer drugs can be classified, in the same way as other psychoactive drugs, into depressants, stimulants, hallucinogens, etc. More commonly, they are classified according to their basic chemical structure, such as fentanyls or phenetylamines. The most important contemporary designer drugs are to be found among the following classes.

Fentanyls

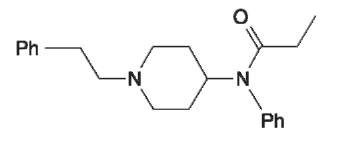

These have the same major properties as opiate narcotics, and they are used in medicine mainly as anesthetics or analgesics (Fig. 1). They are, however, much more potent; some varieties are estimated to be 204000 times as potent as heroin. They may produce intoxication even in the microgram range. One gram (lg) may be sufficient for 10 000 doses. Because of their extreme potency, fentanyls may be difficult to dilute for street sale as intoxicants. Their clandestine synthesis may be extremely profitable: precursors costing USD 200 may produce drugs at a value of USD 2 000 000 on the illicit market. Alphamethylfen-tanyl, diluted and sold under the name ‘China White’ to mimic traditional heroin of extreme purity, was among the first designer drugs to appear on the market (1979) and rapidly caused a number of overdose deaths. The number of drugs in this class is estimated to be around 1400, and the total number of designer opiates 4000.

Methcathinone analogs

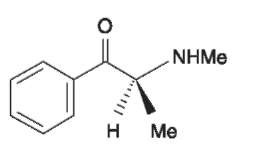

The khat (kath, qat) plant (Catha edulis) contains the central nervous system stimulants cathin (norpseudo-ephedrine) and cathinone. They are both under international control as psychotropic substances, but not the plant per se. Methcathinone (ephedrone) is a synthetic analog of cathinone, and it can easily be produced in a ‘kitchen laboratory’ (Fig. 2). It is highly dependence- and tolerance-forming, and it is often abused in ‘binges’ with intensely repeated administration for several days. Its main effects include severe anorexia, paranoia and psychosis. Homologs of methcatinone, some of which are not under formal drug control, are considered by some to represent a potentially new series of designer drugs yet to be introduced to the nonmedical market. The number of drugs in this class is estimated to be around 10.

Figure 1 Fentanyl. Reprinted from Valter K, Arrizabalaga P (1998) Designer Drugs Directory with permission from Elsevier Science.

Figure 2 Methcathinone. Reprinted from Valter K, Arrizabalaga P (1998) Designer Drugs Directorywith permission from Elsevier Science.

Phencyclidines

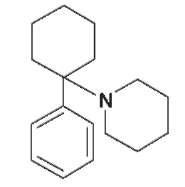

These have both anesthetic and hallucinogenic properties. PCP was originally developed in the 1950s as an anesthetic (Sernyl), but it was withdrawn after it was found to produce severe hallucinations in patients (Fig. 3). Ketamine (Ketalar, Ketanest) is still used as an anesthetic, but it is also abused for its alleged ability to produce a meditative state. Drugs of this type may cause depression, psychosis, personality changes and overdose deaths. The confounding of anesthetic and hallucinogenic properties may make the abuser very difficult to handle in confrontations with the police. The number of drugs in this class is estimated to be 50.

Phenetylamines (PEAs)

These comprise a large group, including such highly diverse substances as amphetamine and mescaline. These drugs can be divided into two subgroups: mainly euphoriant or mainly hallucinogenic. Among the euphoriant PEAs, the most widely known and abused one is MDMA (this was the original ‘Ecstasy’ drug, but this name has also been applied to new varieties such as 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and N-ethyl-3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphe-tamine (MDEA)) (Fig. 4). It has become especially popular among young people at ‘rave’ and ‘techno’ parties. Sometimes these drugs are labeled ‘entacto-gens’ for their alleged ability to increase sensitivity to touch, or ‘empathicogens’, for their alleged ability to create empathy, especially before sexual encounters. They may cause severe neurotoxic reactions due to serotonin depletion (e.g. depression, suicidal behavior and personality changes) and, when taken in connection with physical exercise such as dancing, even rapid fatalities. The predominantly hallucinogenic (psychotomimetic) PEAs include e.g. DOB (4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine), DOM (2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamine), and TMA (3,4,5-Tri-methoxyamphetamine). These drugs may cause or trigger psychotic reactions. The total number of drugs in this class is estimated to be several hundred.

Figure 3 Phencyclidine. Reprinted from Valter K, Arrizabalaga P (1998) Designer Drugs Directorywith permission from Elsevier Science.

Figure 4 MDMA. Reprinted from Valter K, Arrizabalaga P (1998) Designer Drugs Directory with permission from Elsevier Science.

Piperidine analogs

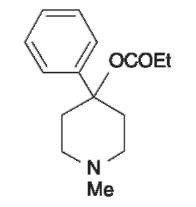

Piperidine analogs are mainly MPPP, MPTP, OPPPP (1-(3-Oxo-3-phenylpropyl)-4-phenyl-4-piperidinol propionate) and PEPAP (1-Phenethyl-4-phenyl-4-piperidol acetate (ester)) (Fig. 5). They have both euphoriant and analgesic properties. They may cause, for example, convulsions and respiratory depression. MPPP is a powerful analgesic but it has never been used in clinical medicine. MPTP has been identified as the causative agent of the frozen addicts syndrome. The number of potential drugs in this class has not been estimated.

Tryptamines

Tryptamines (indolealkylamines) include drugs such as dimethyltryptamine, harmaline, lysergide (LSD) and psilocybine. They produce a variety of reactions, including hallucinations and tremor. LSD was the center of a psychedelic cult in the 1960s, being used for its alleged ‘mind-expanding properties’. The number of LSD analogs is estimated to be 10 and the number of psychotomimetic indolealkylamines is estimated to be several hundred.

Trends and Control Issues

The modern designer drugs represent a new phase in drug synthesis and drug abuse. They have caused fundamental problems for contemporary administrative drug control, forensic investigation and medical services. In reviewing the problem, one author wrote that ‘Designer drugs are subverting the black-market drug trade, undermining and subverting law enforcement activities, and changing our basic understanding of drugs, their risks and the marketplace itself.’

Figure 5 MPPR Reprinted from Valter K, Arrizabalaga P (1998) Designer Drugs Directory with permission from Elsevier Science.

As only a small number of the thousands of varieties of designer drugs have appeared on the nonme-dical market, it is likely that many more will be introduced, tested, abused and, ultimately, administratively controlled.

Over the next years, the emergence of new designer drugs will raise important control issues, such as the criteria and procedures to be used for extending drug control to new substances. This may call for a new definition of drugs (controlled substances), not solely based on administrative drug scheduling but also on the pharmacological properties of the new drugs.

Designer drugs will also raise complicated scientific and medical issues, such as new methods for identifying hazardous substances and treating severe intoxications. They may open new vistas for brain research.

A substantial increase in clandestine production of designer drugs may change the structure of the illegal drug market, making some established forms of production (e.g. heroin from opium poppy) obsolete.