Memnon

Described in the Posthomerica, by Quintus of Smyrna (circa 135 a.d.), as an Ethiopian king who, with his 10,000-man army, came to the aid of besieged Troy after the death of its foremost commander, Hector. “Ethiopia” was, in pre-classical and early classical times not associated with the East African country south of Egypt, but another name for Atlantis, according to the Roman scholar, Pliny the Elder. Memnon said of his own early childhood, “the lily-like Hesperides raised me far away by the stream of Ocean.” The Hesperides were Atlantises, daughters of Atlas, who attended the sacred, golden apple tree at the center of his island kingdom. Having been “raised” by them indicates that Memnon was indeed a king, a member of the royal house of Atlantis.

At his death, he was mourned by another set of Atlantises, the Pleiades, daughters of the sea-goddess Pleione, by Atlas. His mother, Eos, or “Dawn,” bore him in Atlantis, and his father, Tithonus, belonged to the royal house of Troy; hence, his defense of that doomed kingdom. His followers, the Memnonides, wore distinctive chest armor emblazoned with the image of a black crow, the animal of Kronos, a Titan synonymous for the Atlantic Ocean. Even during the Roman era, the Atlantic was known as “Chronos maris,” the Sea of Kronos.

Men Like Gods

A novel about Atlantis by the early 20th-century British author of the better known War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, H.G. Wells.

Gerardus Mercator

The 16th-century cartographer and inventor of the modern globe with its “Mercator lines,” who compared the abundant native flood traditions he heard firsthand in Mexico with Plato’s account of Atlantis to conclude that the lost civilization was fact, not fable. Like many of his contemporaries, he identified America with Atlantis itself.

Merlin

Famous as King Arthur’s magician, his Atlantean, or at any rate, Celtic (even pre-Celtic), origins are widely suspected. The legendary character was probably modeled on a real-life bard who went mad after the Battle of Ardderyd, in 574 a.d., and spent the rest of his life as a hermit in the woods, known for his eccentric genius. “Merlin” was likely derived from Mabon, the all-powerful Lord of the Animals known on the Continent as Cernunnos. He is depicted on Denmark’s second-century Gundestrup Cauldron as a horned stag holding a serpent in one hand and a golden torc (neck ornament) in the other. These symbols appear to signify mastery over the forces of death and regeneration: the horns and snake shed their skins to rejuvenate themselves, while the torc is associated with the eternal light of the sun.

According to Anna Franklin, in her encyclopedic work on world myth, “Some say Merlin came out of Atlantis, and that he and the other survivors became the Druid priests of ancient Britain.” Indeed, he was said to have disassembled Stonehenge and rebuilt it on the Salisbury Plain. His earliest known name, Myrddin, Celtic for “from the sea,” certainly suggests an Atlantean pedigree.

Merope

An Atlantis, daughter of Atlas, one of the seven Pleiades. Her name and variations of it appear in connection with Atlantis among several cultures over a long period of time. Euripides, Plato’s contemporary, who was considered the most realistic of classical playwrights, wrote in “Phaeton” of an island in the Distant West called Merope, a possession of Poseidon, the sea-god creator of Atlantis. Aelian’s Varia Historia quotes the fourth-century b.c. Theopompous of Chios on an island beyond the Pillars of Heracles ruled by Queen Merope, described as a daughter of Atlas. The Merops, according to Theopompous, launched an attack on Europe, first against Hyperborea (Britain).

But the war was lost, and the kingdom of Merope received a sudden increase in population immediately following the fall of Troy. Queen Merope was supposed to have been contemporary with Troy’s Laomedon, King Priam’s father, so she would have lived around the turn of the 14th century b.c., a time when the Atlanto-Trojan Confederation came into effect. These events are dimly shadowed in myth and the name of an historical people, the Meropids, who occupied the Atlantic shores of northern Morocco in the first century b.c. Merope was probably the name of an allied kingdom or colony of the Atlantean Empire in coastal North Africa, perhaps occupying the southern half of present-day Morocco.

Mesentiu

The “Harpooners,” sometimes called “Metal Smiths” in ancient Egyptian tradition, who, along with the “Followers of Horus,” escaped in the company of the gods from their oceanic homeland sinking in the Distant West. They arrived at the Nile Delta, where they created Egyptian Civilization, a fusion of native culture with Atlantean technology. The Mesentiu were a particular group of survivors from one of the Atlantean catastrophes, perhaps the late fourth-millennium event.

Mestor

In Plato’s Kritias, an Atlantean monarch of which nothing is known. Only the meaning of his name, “The Counselor,” suggests Mestor’s kingdom may have been in Britain, where that foremost Atlantean monument, Stonehenge, gave counsel through its numerous celestial alignments. “Merlin” was perhaps a linguistic variant of “Mestor.”

Miwoche

A “Master” with whose birth in 1917 b.c. the history of Tibet officially began. Miwoche is described in the pre-Buddhist Boen religion as directly descended from the spiritual hierarchy that dominated Mu.

Monan

Literally, “the Ancient One” of Brazil’s Tupinamba Indians, who believe he long ago destroyed most of mankind with a “fire from heaven” extinguished by a worldwide flood. Chronologer, Neil Zimmerer, writes that Monan allegedly “enjoyed watching the humans suffer until the island of Atlantis sank.”

Montezuma

Flood hero of the Piman or Papgos Indians of Arizona and Sonoroa, Mexico. He came from a “great land” over the ocean, in the east, where an awful deluge drowned most of his people. His name appears to have been passed down to two Aztec emperors. Moctezuma I was the earliest Aztec emperor, while Moctezuma II was the last such ruler, captured by the Spaniards and stoned to death by his fellow countrymen.

Mo-o

In western Micronesia, an Oleai glyph comprising a smaller circle at the center of a larger one connected at the top and bottom by two vertical lines extending from the outer rim of the inner circle to the inner rim of the larger. It appears to represent the lost civilization of Mu, an island in the middle of the ocean culturally connected to circum-Pacific territories.

Moriori

The white-skinned natives of Chatham Island, lying several hundred miles east of New Zealand. When questioned about their origins by British explorers in the late 18th century, they told how their ancestors arrived at Chatham from a great island kingdom in the west after it sank beneath the sea. The Moriori were shortly thereafter exterminated through their exposure to European diseases, against which they possessed no immunity.

Moselles Shoals

Lying at the same depth, 19 feet, as the Bimini Road, and approximately 5 miles further away to the northeast, Moselles Shoals is a jumbled collection of squared, granite “columns,” resembling the collapsed ruin of a temple or public edifice of some kind. This manmade appearance is enhanced by a total absence of any other stones, megalithic or otherwise, on the sea bottom. At about 30 feet across and perhaps 200 feet long, the “ruin” approximates the dimensions and configuration of an elongated building. Moselles Shoals lies in the same waters with the Bimini Road, but the structures are wholly unlike one another, although they may share a common Atlantean identity. As of this writing, Moselles Shoals has received only a fraction of the attention won by the more famous Road, but concerted investigation there could prove surprisingly rewarding for Atlantologists.

Mu

A Pacific civilization, also known as Lemuria, Kahiki, Ku-Mu waiwai, Horai, Hiva, Haiviki, Pali-uli, Tahiti, and Rutas, that flourished before Atlantis. Far less is known about Mu, but its influence from Asia through the Pacific to the western coasts of America appears to have been prodigious, particularly in religion and art. References to Mu appear among hundreds of often very diverse and otherwise unrelated societies affected by its impact, including Tibet, Easter Island, Olmec Mexico, Indonesia, Australia, Hawaii, Japan, pre-Inca Peru, and so on.

Atlantis and Mu engaged in some cultural interchange, but the peaceful Lemurians mostly regarded imperialist Atlanteans with a veiled mixture of dread and contempt. For their part, the Atlanteans looked down on the people of Mu as members of a backward but colorful and even spiritually valuable, although pre-civilized, society. There were no “cities,” as such, in Mu, but ceremonial centers appeared across the land. Unlike the concentric designs favored by Atlantean architects, monumental construction in Mu was squared and linear, with less spiritual emphasis on the sky (Atlantean astrology) than on Mother Earth. Maritime skills were high, but long voyages were mostly conducted for missionary work.

Nothing in the numerous traditions related to Mu suggests a military of any kind. Its society was unquestionably theocratic, similar perhaps to Tibetan Buddhism, which is, in any case, descended from Mu, with additional alien religious and cultural influences. Also unlike Atlantis, Mu may have actually been “continental,” or, at any rate, a large, mostly flat landmass approaching the size of India, located in the Philippine Sea, southwest of China.

The destruction of Mu is not as well attested as the Atlantean catastrophe, although both events seem to have been generated by a related cause—namely, a killer comet that made repeated, devastating passes near the Earth with increasingly dire consequences for humanity, from the 16th through 13th centuries b.c. A particularly heavy bombardment of meteoritic material around 1628 b.c. may have ignited volcanic and seismic forces throughout the Pacific’s already unstable “Ring of Fire” to bring about the demise of Mu. In Hawaiian myth, a fair-haired people who occupied the islands before the Polynesians and built great stone structures are still remembered as “the Mu.”

Mu’a

An island in western Samoa, featuring prehistoric petroglyphs, burial mounds, and ceremonial structures. Its name and ancient artifacts are associated with the lost Pacific Ocean civilization of the same name.

Mu-ah

Shoshone name, Mu-ah, “Summit of Mu,” for a sacred mountain in California. Mount Mu-ah may have been chosen by Lemurian adepts for the celebration of their religion, and regarded as holy ever since by native peoples.

Muck, Otto Heinrich

Austrian physicist (University of Innsbruck) who invented the snorkel, enabling U-boats to travel under water without surfacing to recharge their batteries, thereby escaping enemy detection in World War II. He later helped develop German rocketry on the research island of Peenemunde, in the Baltic Sea. Published at the time of his death in 1965, The Secret of Atlantis was internationally acclaimed for its scientific evaluation of Plato’s account, helped revive popular interest in the lost civilization, and remains one of the most important topics on the subject.

Mu Cord

An ancient Lemurian flying vehicle described in Tibetan traditions. (See Lemuria, Vimana)

Mu-Da-Lu

Celebrated in Taiwanese folk tradition as the capital of a magnificent kingdom, an ancestral homeland, now at the bottom of the sea. Like Atlantis, Mu-Da-Lu was supposed to have been ringed by great walls of red stone.

Legend seemed confirmed by an underwater find made by Professor We Miin Tian, from the Department of Marine Engineering at National Sun Yat Sen University, in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan. During August, 2002, he discovered a wall standing about 4 feet high, perpendicular to the seafloor. The stone structure is approximately 30 feet long, and 60 feet beneath the surface, among the Pescadores Islands, near the Pen-hu Archipelago, between the small islands of Don-Jyu and Shi-Hyi-Yu, 40 miles west of Taiwan. Twenty years before Professor Tian’s discovery, another scuba diver from Taiwan, Steven Shieh, found a pair of consistently 15-foot high stone walls underwater near Hu-ching, or “Tiger Well Island.” At estimated 2,000 feet long, they run at right angles to each other, one oriented north/south; the other, east/west, terminating in a large, circular structure.

The Pescadores’ sunken walls and tales of Mu-Da-Lu are cultural and archaeological evidence for Lemurian influences in Taiwan. (See Sura and Nako)

Mu-gu

A Chumash village in southern California: “place (gu) near water,” signifying “beach,” although its actual meaning is more likely, “Place near (or toward) Mu.” Variations of “Mu” are more common among the Chumash than any other Native Americans, appropriately so, since their tribe evidenced many Lemurian influences, not the least of which was facial hair among North America’s otherwise beardless peoples, together with their singular skills as boatwrights and mariners.

Mu-Heku-Nuk

“Place-Where-The-Waters-Are-Never-Still,” the oceanic origins of the Algonquian Indians, suggests the geologically unstable, sunken Pacific “Motherland” of Mu.

Mu Kung

In Chinese myth, god of the immortals who ruled over the East, the location of the Pacific civilization of Mu. Mu Kung was an earlier version of Hsi Wang Mu, likewise associated with immortality. He dwelt in a golden palace beside the Lake of Gems, where a blessed peach tree provided fruit from which was distilled the exilir of immortality. Several Lemurian themes are immediately apparent. Chinese explorers actually went in search of the elixir at Yonaguni, a Japanese island where a sunken citadel dated to the 11th millennium b.c. was discovered in 1985. Yonaguni is also known for cho-me-gusa, a plant still revered by the islanders because of its alleged life-extending properties. Moreover, the Japanese myth of “peach boy” concerns a sunken palace of gold, where he never ages.

Chronologist Neil Zimmerer writes that Mu Kung “formed a special group of eight humans, who were given fruits from the Tree of Life. They were known as the ‘Immortals.’” According to Churchward, the Tree of Life,the embodiment of immortality, was Lemuria’s chief emblem. As millennia began to fade clearer folk memories of Mu, the “Motherland,” Hsi Wang Mu’s palace was changed to Kun Lun, the western paradise.

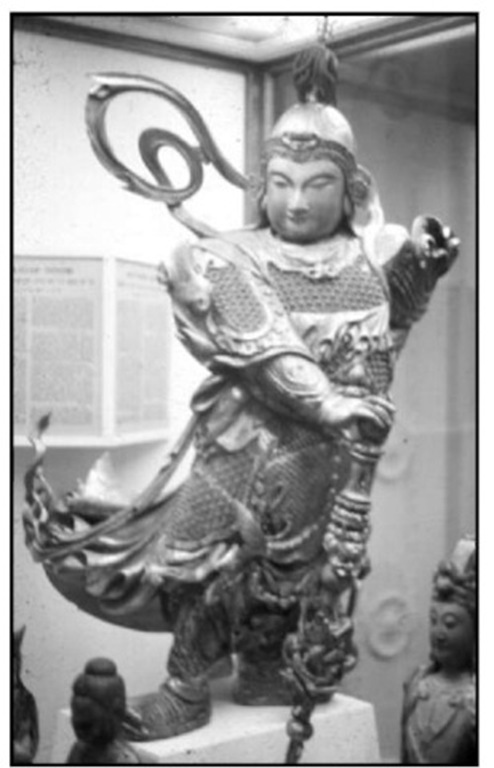

A 17th-century statue of Mu Kung, the mythic ruler of a Pacific Ocean paradise (from which he derived his name) before the island was overwhelmed by the rising sea.

Mu-Lat

California Chumash for “bay,” implying a Lemurian influence.

Mu-luc

Literally, “Drowned Mu,” meaning “flood” in the Mayan language.

Mu-Mu-Na

In Australoid myth, the flaming rainbow serpent, also known as Mu-It, that fell from heaven to cause a world flood. Mu-Mu-Na’s description and name reference the cometary destruction of both antediluvian civilizations, Mu and Atlantis.

Mu Museum

In the aftermath of World War II, Reikiyo Umemto, a young monk, while engaged in deep meditation at the southeastern shores of Japan, experienced a powerful vision of the ancient land of Mu. More than some archaeological flashback, it transcended his traditional Buddhist thinking with the sunken realm’s lost mystery cult, which he refounded as the “World’s Great Equality” in Hiroshima prefecture. For the next 20 years, he lived and shared its principles with a few, select followers, until some wealthy backers put themselves at his disposal. With their support, he built a 12-acre temple-museum with surrounding, landscaped grounds closely patterned after structures and designs recalled from his postwar vision. Work on the red and white complex adorned with life-size statues of elephants and lively, if esoteric murals was undertaken at a selected site in Kagoshima prefecture because of the area’s strong physical resemblance to Mu and the location’s particular geo-spiritual energies. Construction was completed by the mid-1960s.

A large, professionally staffed institute with modern facilities for display and laboratory research, the Mu Museum is unique in all the world for its authentic artifacts and well-made recreations associated with the lost civilization which bears its name. Although open to the general public, spiritual services at its temple are restricted to initiates. Reikiyo Umemto passed away in 2002 at 91 years of age.

Mungan Ngaua

According to chronologist, Neil Zimmerer, a Lemurian monarch who perished with his son, Tundum, in the Great Flood.

Mu-Nissing

Among Michigan’s Ojibwa, an island (Mu) in a body of water (nissing).

Mu-nsungan

Known as the “Humped Island” among the Algonquian-speaking native people of Maine.

Murias

Antediluvian capital of the Tuatha de Danann, described in the Topic of Invasions, a collection of oral histories written during the Middle Ages, as a “sea people” who arrived in ancient Ireland 1,000 years before the Celts, circa 1600 b.c. They were immigrants, survivors of a cataclysm that sank Murias beneath the sea. Some researchers conclude from this characterization, together with its name and alleged location in the far west, that Murias was an Irish version of the sunken Pacific civilization, Mu, or Lemuria.

Before the disaster, the surviving Tuatha de Danann were able to save their most valuable treasure, a mysterious object called “Un-dry,” also known as the “Cauldron of Dagda,” the “Good God,” who led them away from the catastrophe. The same vessel is implied in the most sacred artifact from Murias, “a hollow filled with water and fading light.” The renowned Atlantean scholar, Edgerton Sykes, believed Un-dry was “possibly the origin of the Grail.”

The story of drowned Murias is not confined to Ireland, but known in various parts of the British Isles and the European Continent. In Wales, it is remembered as Morvo, and it is known as Morois, in French Normandy.

Mu-ri-wai-o-ata

Known throughout Polynesia as a legendary palace at the bottom of the sea, home of the divine hero, Toona, an apparent reference to the lost Pacific civilization of Mu.

Murrugan

A god whose worship was carried from Mu to India, where it still flourishes. (See Land of the Kumara)

Musaeus

Listed in Plato’s Kritias as an Atlantean king. He appears to have been deified as Muyscas, the “Civilizer” of the Chibchas. They were a people not unlike the Incas who occupied the high valleys surrounding Bogota and Neiva at the time of the Spanish Conquest. Also known as the “White One,” the bearded Muyscas laid down ground rules for Colombia’s first civilization, then departed, leaving behind four chiefs to govern through his authority and example (Blackett, 274). The Chibchans referred to themselves, after Muyscas, as the Muisca, or “the Musical Ones.” Musaeus, the fifth Atlantean king in Plato’s account, means “Of the Muses,” divine patrons of the arts.

Blackett wrote, “On the common interpretation of mythic traditions, these Atlantides ought to be provinces or places in South America” (215). The Atlantean kingdom of Musaeus was in Colombia, where the native culture came to reflect his name and origins in Atlantis.

Mu-sembeah

A mountain sacred to the Shoshone of Wyoming. Like its California counterpart, Mu-sembeah received its holy character from Lemurian missionaries.

Mu-sinia

The Ute Indians’ sacred “white mountain,” in Utah.

Mu-tu

Tahitian for “island,” possibly derived from the sunken Pacific Ocean island of Mu. Interestingly, its reverse, tu-mu, is Tahitian for “tree,” which may again refer to Mu. According to researcher, James Churchward, Mu was alternately known as the “Tree of Life.”

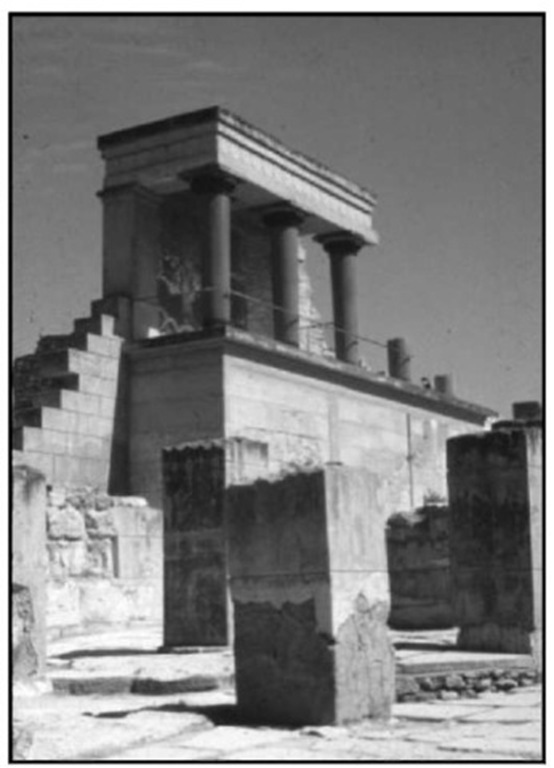

Cretan Knossos shared some architectural similarities with monumental construction in Atlantis, because both evolved into contemporary Bronze Age cities.

Mu-tubu-udundi

A secret martial art known only to masters directly descended from the first king of Japan’s Ryukyu Islands. He brought the regimen with him from his island kingdom in the east, where it was overwhelmed by the sea. Adepts avoid physical confrontation, seeking rather to exhaust their opponents through an intricate series of controlled postures and dance-like movements, striking a blow only after all other options have been exhausted. Like China’s tai-chi, its Japanese precursor is also a form of mediation aimed at putting human bio-rhythms in accord with so-called “Earth energies.” Its name, Mu-tubu-udundi, or “the Self-Disciplined Way of Mu,” derives from the lost Pacific civilization of Mu, similarly known for the spiritual disciplines and peaceful worldview of its inhabitants.

Mu-tu-hei

In Marquesan cosmology, the worldwide void or “silence” that existed during the remote past immediately after the annihilation of a great Pacific kingdom, an apparent reference to the disappearance of Mu.

Mu-tul

A Mayan city founded by Zac-Mu-tul, whose name means, literally, “White Man of Mu.” The name “Mu-tul” seems philologically related to the Polynesian “Mu-tu” (Tahiti) and “Mu-tu-hei” (Marquesas), all defining a Lemurian common denominator.

Mu-yin-wa

The Hopi “maker of all life,” he appears during ritual events known as Powamu, every February. A white line signifying his skin color appears down the front of his arms and legs. Mu-yin-wa’s personification of the Direction Below (sunken Mu?), and the recurrence of “Mu” in his name, to say nothing of the suggestive Powamu, define him as a mythic heirloom from the lost Pacific civilization.

Mu-yu-Moqo

Site of the earliest known working of precious metal in the Andes. Located in the Andahualas Valley, archaeological excavations at Muyu-Moqo uncovered a 3,440-year-old stone bowl containing metallurgical tools and gold beaten into thin foil. The Lemurians were renowned metalsmiths, and the discovery of fine gold work at Muyu-Moqo echoes not only the site’s derivation from Mu, but coincides with the probable destruction of the island civilization, around 1628 b.c