Makila

The ancestral hero of North America’s Pomo Indians. Makila and his son, Dasan, leaders of a bird clan, arrived from “a great lodge” across the Atlantic Ocean to teach wisdom, healing, and magic. The Atlantean features of this myth are clear.

Makonaima

In Melanesian tradition, the last king of Burotu before it sank beneath the Pacific Ocean. He survived with his son, Sigu.

Maler, Teobert

An important Mayanist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who discovered physical evidence for an Atlantean presence in Mesoamerica. Over the course of several decades, he accumulated a vast treasury of exceptionally skillful photographs depicting numerous, previously unrecorded Maya sites in Mexico and Guatemala. These provided a seminal stimulus to the development of Mesoamerican archaeology, and still remain a unique source of material for epigraphic, iconographic, and architectural studies prized by modern archaeologists. Maler has long been recognized as one of the two great archaeological explorers active in the Maya area at the dawn of professional studies in Middle American history, the other being Alfred Maudslay. Had it not been for them, later scholars would have been seriously handicapped by a lack of reliable data, and the development of Maya archaeology would have been delayed by decades.

Austrian-born Teobert Maler came to Mexico in 1864 as a volunteer in an Austrian military expedition supporting the imperial claims of Archduke Maximilian. Although Maximilian was toppled in 1867, Maler made Mexico his adoptive home, where he became a professional nature photographer. His subject matter eventually included the country’s pre-Columbian ruins, which so fascinated him that he was eventually recognized as a self-taught but brilliant expert in local archaeology. Documenting these structures soon evolved into his life’s work, and he traveled widely throughout Mexico and Central America in search of ancient sites, some of which he discovered himself.

During 1885, he settled in the quiet little Yucatan town of Ticul, and there established a photographic studio, while becoming proficient in the Mayan language. Throughout the course of his studies and explorations, he was a valued contributor to the German geographic-ethnographic magazine, Globus, and other scientific journals. His sets of large prints, uniformly mounted, supplemented by site plans and other information, were sought after by museums and universities in both Europe and America, including Harvard’s Peabody Museum, which sponsored his survey—the first ever—of Palenque and its environs.

Although vaguely familiar with Plato’s account of Atlantis, Maler, like most scholars, then and now, dismissed the lost civilization as mere fantasy. However, while photographing the so-called “acropolis” at the ninth century Maya ceremonial city of Tikal, in Guatemala, he discovered, in his words, “a water scene with a volcano spouting fire and smoke, buildings falling into the water, people drowning.” It was at the start of a sculpted frieze that ran around the uppermost part of the building in an apparent visual representation of Maya history. Until Maler’s photographic expedition to Tikal, the extensive ruins there were virtually unknown to the outside world. Astounded by the “water scene,” he was convinced it depicted Maya origins in Atlantis, and removed the panel to the Voelkerkunde Museum, in Vienna. It was part of the institution’s permanent Mesoamerican display until 1945, when it disappeared among the general looting by invading Soviet troops at the end of World War II. Fortunately, his photograph of the Atlantean panel survives at the University of Pennsylvania.

Long after his death on November 22, 1917, in the Yucatan city of Merida, Maler is still recognized by the academic community for his invaluable photographic and surveying services to Mesoamerican archaeology, although deplored for his courage in describing evidence of Atlantis among the Mayas he knew so well for most of his adult life.

Mama Nono

Before their extinction through exposure to European diseases against which they had no immunity, Caribs of the Antilles told the Spaniards that Mama Nono created the first new race of human beings. She achieved this act of regeneration by planting stones in the ground after a great flood that wiped out all life on Earth.

In Greek myth, the deluge heroes, Deucalion and Pyrrha, were counseled to repopulate mankind by throwing stones over their shoulders. As the stones fell to the ground, men and women sprang up in their place. This myth, known in its variants among widely scattered cultures around the Earth, is a shared metaphor for the repopulation of a badly wounded world by survivors of the Atlantean holocaust. In Britain, local traditions often recount that the standing stones of megalithic circles are petrified humans, such as the “Whispering Knights.”

Mama Ocllo

Also called “Mama Oglo,” she was the companion of Manco Capac, who survived a great flood by seeking refuge among the high Bolivian mountains, at Lake Titicaca. Children born to her in South America were the progenitors of all Andean royalty.

Man Mounds

Two effigy earthworks, of gigantic proportions, in Wisconsin. They represent the water spirit that led the Wolf Clan ancestors of the Winnebago, or Ho Chunk Indians, to safety in North America after the Great Flood. One of the geoglyphs still exists, although in mutilated form, on the slope of a hill in Greenfield Township, outside Baraboo. Road construction cut off his legs below the knees around the turn of the 20th century, but the figure is otherwise intact. The giant is 214 feet long and 30 feet across at his shoulders. His anthropomorphic image is oriented westward, as though striding from the east, where the Deluge was supposed to have occurred. His horned helmet identifies him as Wakt’cexi, the flood hero.

The terraglyph is no primitive mound, but beautifully proportioned and formed. Increase Lapham, a surveyor who measured the earthwork in the early 19th century, was impressed: “All the lines of this most singular effigy are curved gracefully, and much care has been bestowed upon its construction.”

A companion of the Greenfield Township hill-figure, also in Sauk County, about 30 miles northwest, was drowned under several fathoms of river by a dam project in the early 20th century. Ironically, the water spirit that led the Ho Chunk ancestors from a cataclysmic flood was itself the victim of another, modern deluge.

The Atlantean identity of Wakt’cexi as materialized in his Wisconsin effigy mounds is repeated in an overseas’ counterpart. The Wilmington Long Man is likewise the representation of an anthropomorphic figure—at 300 feet, the largest in Europe—cut into the chalk face of a hill in the south of England, about 40 miles from Bristol, and is dated to the last centuries of Atlantis, from 2000 to 1200 b.c. Resemblances to the Wisconsin earthwork grow closer when we learn that the British hill-figure was originally portrayed wearing a horned helmet obliterated in the early 19th century. A third man-terraglyph is located in the Atacama desert of Chile’s coastal region. Known as the Cerro Unitas giant, it is the largest in the world at 393 feet in length. It, too, wears a horned headgear, but more like an elaborate rayed crown.

The Old and New World effigy mounds appear to have been created by a single people representing a common theme—namely, the migration of survivors from the Atlantis catastrophe led by men whose symbol of authority was the horned helmet. Indeed, such an interpretation is underscored by the Atlantean “Sea People” invaders of Egypt during the early 12th century, when they were depicted on the wall art of Medinet Habu, wearing horned helmets.

Manco Capac

Described as a bearded, white-skinned flood hero, who arrived at Lake Titicaca, where he established a new kingdom. In time, however, the native peoples rose against him, massacring many of his followers. These events forced him to relocate the capital to Cuzco, where all subsequent Inca emperors were obliged to trace their lineal descent from Manco Capac.

Mangala

As described in Benin and Yoruba myth, he was deliberately left behind to die on a kingdom in the Atlantic Ocean when the island sank beneath the sea, but survived in a water-tight vessel built for himself and his followers. They arrived on the shores of West Africa, where an earlier flood survivor, Amma, had already installed herself as the first ruler. After her death, Mangala’s claim to the throne was opposed by a twin brother. Pemba was eventually banished, however, and Mangala became West Africa’s first king, from whom all subsequent dynasties trace their descent.

In many lands touched by the Atlantis phenomenon, ruling families commonly traced their lineage to escaped royalty from a cataclysmic deluge.

Manibozho

The Algonquians’ great creation hero and survivor of the Deluge which submerged the Earth. From his place of refuge atop the tallest tree at the center of the world, the Tree of Life encountered in universal tradition, Manibozho sent forth a crow, but it returned after several days to say that the waters had not yet receded. Another failed attempt was made with an otter. Finally, a muskrat was able to report that land was beginning to emerge. Manibozho swam to the new territory, where he reestablished human society, and became the founder of the Algonquians’ oldest, most venerated tribe, the Musk-Rat.

Manibozho was the Algonquian forefather from Atlantis. His Native American version of the Great Flood bears some resemblance to the Genesis account, in which Noah dispatches birds to inform him about the receding waters.

Manoa

The Portuguese royal historian, Francisco Lopez, recorded his account of an oceanic capital which once sent “visitors” to the Brazilian natives: Manoa is on an island in a great salt lake. Its walls and roof are made of gold and reflected in a gold-tiled lake. All the serving dishes for the palace are made of pure gold and silver, and even the most insignificant things are made of silver and copper. In the middle of the island stands a temple dedicated to the sun. Around the building, there are statues of gold, which represent giants. There are also trees made of gold and silver on the island, and the statue of a prince covered entirely with gold dust. Manoa’s resemblance to Plato’s opulent Atlantis, with its Titans and oceanic location “on an island in a great salt lake” is apparent.

Manu

India’s flood hero. In the Matsyu Purana, his version of the deluge features a rain of burning coals. Warning Manu of the catastrophe to come, the god Vishnu, in the guise of a fish, says, “the Earth shall become like ashes, the aether too shall be scorched with heat.” Oppenheimer observes that “the details suggest a grand disaster, such as may follow a meteorite strike.”

Marae Renga

A homeland in the east from which the chief culture-bearer, Hotu Matua, with his family and followers, arrived at Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, to replant civilization there. Marae Renga was itself an island belonging to the larger kingdom of Hiva, before it was sunk by the earthquake-god, Uwoke, with a “crowbar.”

Marerewana

The Arawak Indians’ foremost culture hero, who escaped the Deluge in a “great canoe” with his followers. Spanish Conquistadors in the 16th century noted occasional blondism, somewhat European facial features, and light eyes among the Arawak—physical throw-backs to their ancient Atlantean genetic heritage.

Marumda

Together with his brother, Kuksu, he virtually destroyed the world by fire and flood, according to the Pomo Indians of Central America. The savior of threatened humanity was the Earth-Mother goddess, Ragno.

Marumda combines a celestial cataclysm with the deluge common in Atlantean traditions around the world.

Masefield, John

Early 20th-century British poet laureate renowned for his innovative verse. In his 1912 “Story of a Roundhouse,” he told how “the courts of old Atlantis rose.”

Mataco Flood Myth

The Argentine Indians of Gran Chaco describe “a black cloud that came from the south at the time of the flood, and covered the whole sky. Lightning struck and thunder was heard. Yet the drops that fell were not like rain. They fell as fire.” Here, too, a celestial event coincides with the deluge in a South American recollection of the Atlantean catastrophe.

Medinet Habu

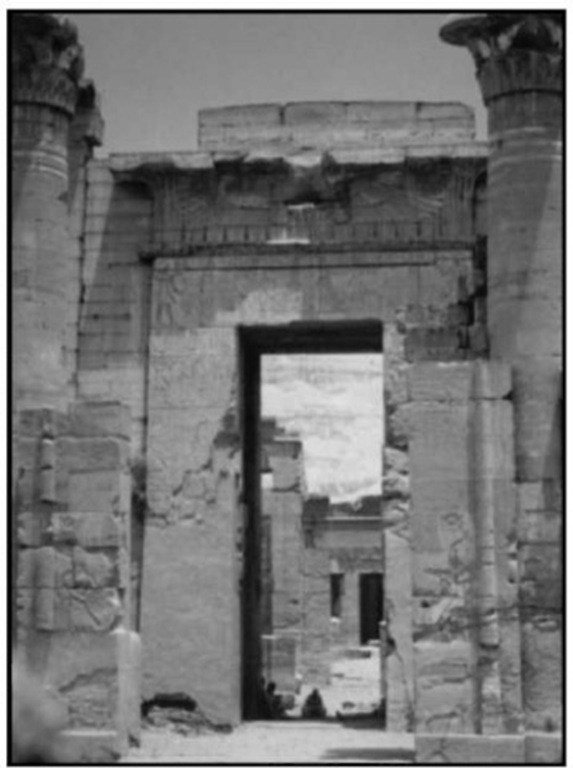

The “Victory Temple” of XX Dynasty Pharaoh Ramses III at West Thebes, in the Upper Nile Valley, completed around 1180 b.c. It is the finest, best preserved example of large-scale sacred architecture from the late New Kingdom, and built as a monument to his important triumph over a massive series of invasions launched by the “Sea People” against the Nile Delta at the beginning of the 12th century b.c. The exterior walls of Medinet Habu are decorated with lengthy descriptions of the war and illustrated by incised representations of the combatants.

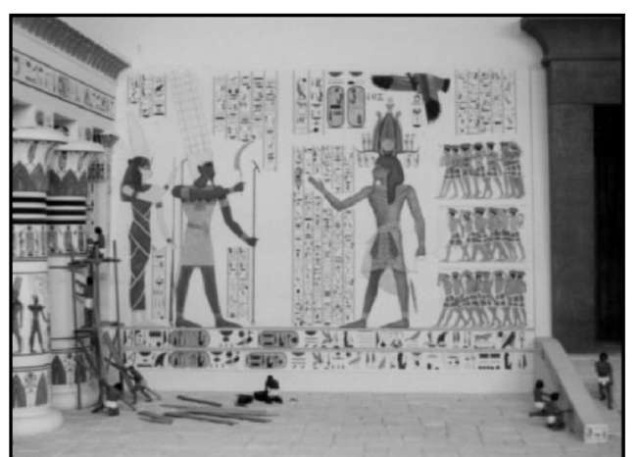

Recorded testimony of captured “Sea People” warriors leaves no doubt about their Atlantean identity. The text quotes them as saying they came from an island the Egyptians transliterated as “Netero,” like Plato’s Atlantis, a “sacred isle,” in the Far West after it had been set ablaze by a celestial event identified with the fiery goddess Sekhmet and sank into the sea. Medinet Habu’s profiles of various “Sea People” invaders are the life-like portraits of Atlanteans in the Late Bronze Age.

The grand entrance of Medinet Habu, Ramses III’s monument to his victory over Atlantean invaders.

Medinet Habu as it appeared when approaching final construction, around 1180 B.C. A gigantic Ramses III, impersonating Amun-Ra, presents the captured armies of Atlantis to his fellow gods. Model, Milwaukee Public Museum, Wisconsin.

Mee-nee-ro-da-ha-sha

The Mandan Indians’ annual “Settling of the Waters” ceremony commemorating the Great Flood from which a white-skinned survivor arrived in South Dakota.

Meg

“Before the second of the upheavals,” this priestess, according to Edgar Cayce, “interpreted the messages that were received through the crystals and the fires that were to the eternal fires of nature” (natural energies). In Meg’s time, there were “new developments in air, in water travel…there were the beginnings of the developments at that period for the escape.” Although the first examples of this evacuation technology were becoming available, “when the destructions came, the entity chose rather to stay with the groups than to flee to other lands” (3004-1 F.55 5/15/43).

In ancient British myth, Meg was a giantess able to throw huge boulders over great distances. Her memory still survives in the Royal Navy, where battleship guns are referred to as Mon Megs, from Long Meg. It is not inconceivable that Cayce’s Meg and the Atlantean cataclysm were transmuted over time into the British Meg, whose myth seems to describe an erupting volcano at sea.

Megas

See Saka Duipa

Meh-Urt

Literally “The Great Flood,” she was the Egyptian “Goddess of the Watery Abyss,” from whose deluge all life sprang. She was usually portrayed as “the Celestial Cow” wearing a jeweled collar and a sun disk resting between her horns. At other times she appeared as a woman with the head of a cow, while carrying a lotus-flower scepter. Me-Urt represented creative destruction, which annihilated older forms to bring forth new ones, such as Nile civilization from the early Atlantean “Great Flood” in the late fourth millennium b.c.