PHARYNX

The pharynx is a passageway about 5 inches (12.7 cm) long, used for both food and air (see Fig. 25-1). Its areas are named in relationship to location. The nasopharynx, which is located behind the nasal cavity, is lined with ciliated columnar pseudostratified epithelium. The oropharynx lies behind the oral cavity (mouth) and is lined with stratified squamous epithelium. The laryngopharynx (hypopharynx) has the same lining and is situated just below the epiglottis. In this area, the respiratory and digestive tubes divide. (The larynx is located directly in front of the pharynx and is the structure through which air passes into the lungs.) Because the larynx and pharynx are so close together, a special mechanism, the epiglottis, prevents aspiration of food and fluids into the lungs when a person swallows. This flap of tissue drops down to cover the larynx and trachea (windpipe) during swallowing. (Food has the “right of way” over air at this point.)

In the mouth, the tongue lifts and moves the bolus of food, mixed with saliva. The initial swallowing of food is voluntary. The tongue pushes the bolus into the pharynx, where the movement becomes involuntary. (Here, the medulla’s swallowing center takes over.) Contractions of the pharynx push food into the muscular esophagus. The entire digestive tract, including the pharynx, is lined with mucous membrane. The smooth (involuntary) muscles pass food through the entire GI tube by waves of contractions called peristalsis, an alternating relaxation and contraction of muscles. Two layers of smooth (involuntary) muscles are involved. The outer layer of esophageal muscles runs up and down (longitudinal); the inner layer lies in concentric circles. Digestion cannot occur without peristalsis.

Key Concept The medical term for difficulty in swallowing is dysphagia.

ESOPHAGUS

The esophagus, or gullet, is approximately 10 inches (25.4 cm) in length; it extends from the pharynx into the neck and thorax and, through an opening in the diaphragm, to the stomach. The role of the esophagus in digestion is to serve as a passageway. A strong circular muscle lies between the esophagus and stomach. This is the cardiac sphincter or lower esophageal sphincter (LES); sometimes called the gastroesophageal sphincter. This sphincter guards the opening of the stomach by preventing food from backing up into the esophagus. As waves of peristalsis push food through the lower esophagus, the LES opens (allowing food to enter) and closes (to keep food in the stomach).

Nursing Alert

♦ If the LES does not relax as it should, food can be prevented from entering the stomach. This condition is known as achalasia,

♦ If the LES does not close adequately the stomach contents can re-enter the esophagus. Because the stomach contents are very acidic, a severe burning sensation can result. This condition is known as heartburn or acid reflux. If this continues, it can lead to esophageal or gastric (stomach) ulcers. Acid reflux often can be successfully treated with medications and

Special Considerations: LIFESPAN

The GI system is immature in an infant. Therefore, regurgitation ("spitting up”) of feedings (breast milk or formula) is common. This immaturity gradually improves and usually resolves around 3 months of age. "Burping” or "bubbling” the baby helps to remove excess air and gas from the stomach.

Key Concept No digestion takes place in the esophagus. Food passes through it in about 5 to 10 seconds.

STOMACH

Food begins the gastric or peptic phase of digestion when it enters the stomach (gaster), a C-shaped muscular, collapsible pouch or sac capable of being greatly distended (expanded). It has a volume of approximately 1/5 cup when empty; but can expand to hold more than 8 cups after a meal. The stomach is located in the upper left side of the abdominal cavity and receives its blood supply from the celiac artery. The rounded portion above the level of the cardiac sphincter, in which is located the opening from the esophagus, is called the fundus (Fig. 26-4). The central and largest portion is called the body; the lower narrow portion, which attaches to the small intestine, is called the pylorus. The walnut-sized pyloric sphincter controls the opening between the stomach and the duodenal portion of the small intestine. (The prefix referring to the stomach is gastr[o]-.)

Special Considerations :LIFESPAN

In infants, projectile vomiting (vomiting with great force) can be a sign of pyloric stenosis (a narrowing of the pyloric sphincter). This can be life-threatening.

The outside of the stomach is covered by serous membrane. Next, is a thick pad of muscles. These muscles lie in three layers; the first is a longitudinal layer (muscle fibers going the long way, from top to bottom). The center layer consists of muscle fibers that encircle the stomach. Innermost, is an oblique layer (muscle fibers on a slant or angle). The spread and action of these muscles stir and churn food, break it into small particles, and move it through the system. When the stomach is empty, it collapses and lies in folds called rugae. These rugae allow the stomach to distend greatly when food is eaten.

FIGURE 26-4 · Longitudinal section of the stomach and a portion of the duodenum. Rugae and the three muscle layers are shown.

Key Concept The entire digestive tract, from the pharynx to the anus, contains longitudinal and circular muscle fibers. Only the stomach contains an oblique muscle layer

Under the muscular layer of the stomach lies the submucosa. In this layer, connective tissues contain nerves, as well as blood and lymph vessels. The innermost layer of the stomach is the extensively folded mucosa, which is connective tissue covered with gastric glands. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, gastric acid) and pepsinogen (which leads to the enzyme, pepsin) are secreted here. In addition, this layer secretes mucus, which lubricates food and protects the lining of the stomach from the acids and other gastric juices.

Key Concept Layers of the stomach wall:

• Serous membrane (outer wall)

• Muscles—longitudinal, horizontal, oblique

• Submucosa—contains nerves, blood/lymph vessels

• Mucosa (mucous membrane)—contains gastric glands that secrete mucus, HCl, hormones, and precursors to digestive enzymes, such as pepsinogen.

In the stomach, all foods mix with mucus and gastric acid, as well as pepsin and other digestive enzymes (about 3 quarts—2.8 liters a day). These substances churn until they are in a semi-liquid, milky form called chyme (pronounced “kime”). This process usually takes 3-5 hours. (The parietal cells of the stomach also secrete intrinsic factor, which allows the body to absorb vitamin B12.) Peristalsis of the stomach muscles moves food toward the pyloric outlet. The pyloric sphincter at the lower opening of the stomach contracts to keep food in the stomach until it is thoroughly mixed. The sphincter then relaxes to let peristaltic waves squirt food in small amounts into the small intestine. (Although most nutrients move as chyme into the small intestine, some small molecules, such as alcohol, are directly absorbed into the blood stream from the stomach.)

If the stomach is irritated or too full, sometimes the direction of the peristaltic waves reverses and forces material back into the lower end of the esophagus. Reverse peristalsis within the stomach, combined with contractions of abdominal muscles and the diaphragm, forces food back through the esophagus and out through the mouth, referred to as vomiting (emesis).

Key Concept Stomach acid does not break down food particles. It provides the proper acid-base environment so digestive enzymes can do their work. It prepares proteins for digestion. The acid also kills unwanted microorganisms ingested with food.

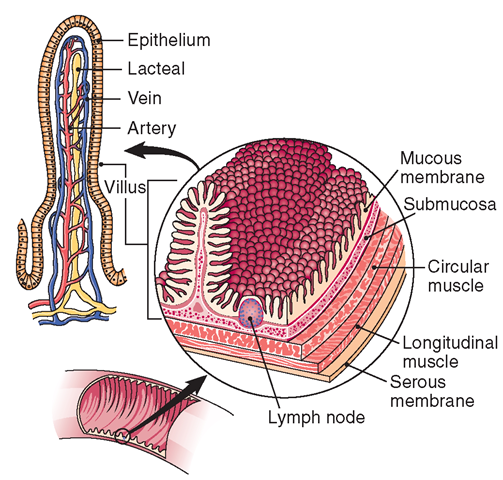

SMALL INTESTINE

The intestinal phase of digestion begins with the small intestine (see Fig. 26-1). The small intestine is the longest part of the digestive tract, approximately 20 feet (6.1 m) long and 1.5 inches (3.81 cm) in diameter. It lies coiled on itself so it can fit into the abdominal cavity. It is about 18 feet longer than the large intestine, which follows it. (The prefix referring to the intestines is enter[o]-.) The areas of the small intestine are the duodenum (see Fig. 26-5), the jejunum (midsection), and the ileum (terminal section). Food elements move through these areas of the small intestine while being altered by a variety of secretions and enzymes. The small intestine consists of the same tissue layers as the stomach, with the exception of oblique muscles (Fig. 26-5). The smooth (involuntary) longitudinal and circular muscles here are antagonistic, that is when one contracts, the other relaxes. The wave-like contractions of the circular muscles narrow the lumen of the intestine, squeezing food onward. When the longitudinal muscles contract, the circular muscles relax, increasing the size of the lumen and allowing food to pass. These rhythmic waves constitute intestinal peristalsis.

FIGURE 26-5 · The wall of the small intestine, showing numerous villi. At the left is an enlarged drawing of a single villus.

Most digestive processes occur in the small intestine. Intestinal glands in the mucous membrane lining the small intestine secrete enzymes for the digestion of all foods. These intestinal enzymes are proteins that act as catalysts, promoting and speeding up chemical reactions, but not actually undergoing changes themselves. These enzymes break carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into materials the cells can use. To be absorbed by the blood and lymph capillaries, carbohydrates must be in the form of simple sugars—monosaccharides: glucose, fructose, and galactose. Proteins must be digested into their simplest state, amino acids; fats must be converted to fatty acids and glycerol.

Key Concept Very few chemical reactions in the body can occur without catalysts. Each enzyme facilitates specific chemical reactions. For example:

♦ Maltase—maltose into glucose

♦ Lactase—lactose into galactose and glucose

♦ Sucrase—sucrose into fructose and glucose

♦ Pepsin, trypsin, chymotrypsin, carboxypeptidase, aminopepti-dase, dipeptidase—proteins into amino acids

The small intestine has numerous secretions, not just enzymes. Mucus lubricates and protects the intestinal wall lining from the highly acidic chyme and digestive enzymes. Cholecystokinin is a secreted hormone that stimulates the pancreas to secrete pancreatic juice and the gallbladder to contract, resulting in the release of bile. (Bile is secreted in the liver and acts to digest fats—lipids). Secretin is another hormone that influences the secretion of pancreatic juice by the pancreas. Pancreatic juice contains bicarbonate ions (HC03), which combine with sodium ions (Na+) to form sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3). This is a basic (alkali) substance which helps to neutralize the very acidic chyme (Table 26-2).

DUODENUM

The first portion of the small intestine is the 10- to 12-inch C-shaped duodenum (see Figs. 26-1, 26-4, and 26-6). The duodenal wall contains specialized cells and glands designed to secrete mucus which helps protect the small intestine from the acidic chyme. As chyme enters the duodenum, more digestive juices are added. Bile, a greenish brown liquid manufactured by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, pours in through the common bile duct to emulsify fats in preparation for further digestive action.

JEJUNUM AND ILEUM

Chyme travels through the remaining portions of the small intestine, the jejunum (about 8 feet long), and the terminal ileum (about 11 feet long). (The word jejunum derives from a Latin word meaning “fasting intestine”; it has been so named because, when dissected, the jejunum is almost always empty. The word ileum means “flank” or “groin.”) The entire small intestine is lined with mucous membrane. Numerous lymph nodules are in the ileum, both solitary and grouped. Those grouped together are called aggregated lymphatic follicles or Peyer’s patches.

A sphincter-like muscle, located where the large and small intestines meet, acts as a valve to prevent backflow of material to the small intestine; it also regulates the forward flow. This is the ileocecal valve, from the names of the two joining parts: the ileum of the small intestine and the cecum of the large intestine.

Key Concept As the acidic chyme passes through the digestive tract, it becomes more basic (less acidic). This allows the enzymes to function even more effectively to break down nutrients into their simplest forms and facilitate absorption into the blood stream.

LARGE INTESTINE

The large intestine, as with the remainder of the GI tract, is lined with mucous membrane. The large intestine is much wider than the small intestine (its diameter is approximately 2.5 inches, or 6.35 cm), but it is only about 5 feet (1.5 m) long. It does not coil, but lies in folds, and is divided into areas called the cecum, colon, and rectum. Water reabsorption is the large intestine’s main function. Intestinal bacteria function to inhibit the growth of pathogens in the large intestine and some produce vitamin K, which is necessary for blood clotting. Absorption of vitamins and minerals and the formation and defecation (egestion) of feces are also functions of the large intestine.

COLON

The next and longest portion of the large intestine is the colon, a continuous tube classified into three areas, which take their names from the course they follow. The ascending (going up) colon travels up the right side of the abdominal cavity; the transverse (going across) colon crosses to the left side in the upper part of the cavity; and the descending (going down) colon goes down the left side into the pelvis. (The first two portions absorb fluids, salts, and vitamins; the descending colon holds the resulting wastes. The next and last portion,which is called the sigmoid (sigma is the Greek letter S) colon, ends at the rectum and stores the feces until defecation (a bowel movement) occurs. Figure 26-1 illustrates the colon.

TABLE 26-2. Digestive System Secretions and Their Actions

|

AREA OF DIGESTIVE SYSTEM |

SECRETION |

ENZYME |

ACTION |

|

Mouth Salivary glands |

Saliva (also contains water, mucus, and salts) |

Salivary amylase (ptyalin) |

Begins to break down starch into simpler carbohydrates, such as dextrin Assists swallowing Softens and lubricates food Dissolves some food components |

|

Stomach Stomach lining |

Mucus Mucin |

Protects lining Stimulates secretion of gastric acid (HCl) and pepsin |

|

|

Specialized cells of pyloric glands |

Gastrin (regulatory hormone) |

Weakly stimulates secretion of pancreatic enzymes and HCl Stimulates contraction of gallbladder Stimulated by arrival of food in stomach; inhibited by low pH (acids) |

|

|

Parietal cells |

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) |

Hydrolyzes some CHO (carbohydrates) into glucose and fructose Destroys microorganisms |

|

|

Changes pepsinogen to pepsin |

|||

|

Intrinsic factor |

Needed for absorption of vitamin B12, which is needed for development of red blood cells (RBCs) (also requires folate) |

||

|

Chief cells |

Pepsinogen Gastric lipase |

Pepsin Lipase |

Begins digestion of proteins into polypeptides Begins digestion of fats by breaking down triglycerides (very little occurs in stomach); acts only on emulsified fats |

|

Kidney (juxtaglomerular cells) |

Renin |

Regulates blood pressure |

|

|

Liver |

Bile |

Emulsifies fat to fatty acids, so they can be absorbed Helps neutralize the acidic chyme; provides proper pH for enzyme function Excretes bilin and bile acids |

|

|

Pancreas |

|||

|

Acinar cells (exocrine function) |

Pancreatic juice |

Amylase Lipase |

Breaks down dextrin into maltose Breaks down fats into monoglycerides and fatty acids |

|

Trypsin |

Break proteins into amino acids |

||

|

Chymotrypsin |

|||

|

Carboxypeptidase |

|||

|

Aminopeptidase |

|||

|

Dipeptidase |

|||

|

Bicarbonate ions |

Helps neutralize acids, to facilitate enzyme action |

||

|

Pancreas (endocrine function) |

Insulin (hormone) Glucagon (hormone) Somatostatin (hormone) |

Enables cells to use glucose Elevates blood sugar levels Inhibits release of glucagon and insulin |

|

|

Small Intestine Duodenum and jejunum |

Cholecystokinin—CCK (hormone secreted in response to presence of fat) |

Activates gallbladder to release bile Stimulates pancreas to secrete pancreatic juice |

|

|

Secretin (hormone) |

Stimulates secretion of pancreatic juice and some bile Stimulates secretion of bicarbonate ions from pancreas. (Responds to acid in chyme.) |

||

|

Bile from gallbladder Pancreatic juice from pancreas |

Pancreatic protease (trypsin) |

Breaks fats into tiny droplets (emulsification) Splits proteins into amino acids |

|

|

V / r V Chymotrypsin |

More complex proteins broken down in intestine and at brush border |

||

|

Carboxypeptidase |

Stimulates release of water and HCO3_ from pancreas |

||

|

Pancreatic amylase (and intestinal amylase) |

Converts complex CHO into maltose and isomaltose |

||

|

Gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) |

Pancreatic lipase Intestinal lipase Sucrase |

Breaks down emulsified fat into fatty acids, glycerol, and monoglycerides Completes digestion of monoglycerides Breaks sucrose into fructose* and glucose* (In duodenum)—decreases churning of stomach to slow stomach emptying. Induces insulin secretion. |

|

|

Intestinal wall mucosa |

Maltase |

Breaks maltose into glucose |

|

|

Lactase |

Breaks lactose into glucose and galactose* |

||

|

Protein enzymes (peptidases) |

Assist in digestion of proteins |

*Complex carbohydrates must be broken down into monosaccharides (simple sugars) before they can be absorbed through the intestinal mucosa. The monosaccharides are glucose, fructose, and galactose. Fiber is mostly excreted undigested.

RECTUM AND ANUS

The rectum is about 5 inches (12.7 cm) in length and terminates at the anal canal, the terminal (end) portion of the large intestine, which is about 1-1.5 inches long (2.54-3.8 cm). Waste products are excreted (egestion) via the opening to the outside (anus), which is guarded by internal and external sphincter muscles. The external sphincter is under a person’s control and can be consciously contracted and relaxed.

Key Concept The pathway of food materials through the body is as follows: mouth —> pharynx —> esophagus S (cardiac sphincter) S stomach S (pyloric sphincter) S small intestine (duodenum S jejunum S ileum) S (ileocecal valve) S large intestine (cecum S colon: ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid S rectum) S anus.