In comparison to China and Japan, as well as Thailand and other regions of Southeast Asia, India does not often come to mind as a country with a strong martial arts tradition. Indeed, Indian civilization is most often associated with elaborate ritual codes, abstract metaphysical speculation, and, at least in modern times, the principle of nonviolence. Even though the so-called classical scheme of social classification known as varna clearly defined the role of warrior princes in relation to other occupational groups and the two preeminent epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, are replete with military exploits and martial heroes, Indian civilization has come to be associated with the values of Brahmanic Hinduism and colored by the values of orthodox ritual religiosity on the one hand and contemplative, otherworldly speculation on the other. In both public conception and much of the academic literature, these attributes are conceived of as decidedly noncombat-ive and, very often, abstracted from the body rather than linked to it.

Nevertheless there is a strong tradition of martial arts in South Asia, as D. C. Muzumdar brought out in his topic of Indian Physical Culture, published in 1950, and this tradition is not nearly as dissociated from the so-called mainstream of spiritualism and philosophical thought as popular perception would have it. In practice, the martial arts in India are clearly marginalized, and their popularity is sharply limited, but in theory various forms of martial art are closely linked to important medical, ritual, and meditational forms of practice. Moreover, it is somewhat problematic to think of the martial arts in India as a discrete entity upon which an equally discrete entity—spirituality and religion—has a direct effect. When, as in South Asia, the distinction between mind and body is not applicable, other categorical binary distinctions also tend to lose their meaning. As a result, what might be classified as religion shades into metaphysics, which, in turn, shades into physical fitness. Thus, in a sense, devotionalism, meditation, and the martial arts are, perhaps, best seen as part of the same basic complex rather than as interdependent variables.

The concept of shakti (Hindi; power/energy) or its various analogs, such as pran (vital breath), is of central importance to this complex. Most broadly, shakti as a metaphysical concept denotes the active, or animating, feminine aspect of creation. It also means cosmic energy or, simply, the supernatural power associated with divine beings and spiritual forces. Shakti is regarded as a kind of power that pervades the universe, but that does not always manifest itself as such. To the extent that human beings are micro-cosmic, they are thought to embody shakti, and this shakti can be made manifest in various ways under various circumstances.

Most often one is said to manifest shakti when one so closely identifies with a deity that one embodies that deity’s power. Moreover, the performance of austerities, such as fasts and other forms of renunciation, as well as various forms of ritualized sacrifice, produces shakti. Thus, shakti is thought of as something that can be developed through practice, and this, in particular, is what links it to the performance of various martial arts. Most significantly, shakti is at once supernatural and therefore meta-physical and physical and physiological. The brightness of one’s eyes as well as the tone of one’s skin is said to be a manifestation of shakti, as is the ability to levitate, on the one hand, or lift an opponent into the air, on the other. In other words, shakti means many different things, which makes it possible to translate across various domains of experience, and the martial arts can be thought of as a critical, if often overlooked, point at which this translation is most clearly worked out.

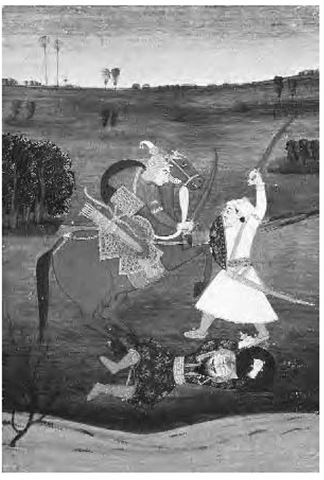

An Indian miniature of the defeat of a devil by a prince on horseback and a warrior, Ragmala Bikaner school, 1765.

Whereas shakti can be derived from devotional and ascetic practices, it is perhaps most closely linked, and clearly embodied, through the practice of brahmacharya (celibacy; the complete control of one’s senses). In this way, shakti is directly linked to sexual activity, and the physiology of masculine sexuality in particular. Essentially, shakti becomes manifest when a person is able to renounce sexual desire and embody the energy manifest in semen. As Swami Sivananda of the Divine Life Society, one of the most highly regarded spiritual leaders of the twentieth century, puts it: “The more a person conserves his semen, the greater will be his stature and vitality. His energy, ardor, intellect, competence, capacity for work, wisdom, success and godliness will begin to manifest themselves, and he will be able to profit from long life. … To tell the truth, semen is elixir” (1984, 10-11). Semen itself is thought of as the distilled, condensed essence of the body, as the body, nourished by food, goes through a series of biochemical metabolic transformations whereby waste products are purged and each successive metamorphosis is a more pure, refined form of the previous one. In fact, semen is thought of as the purest and most powerful of body fluids, derived from the juice of food, blood, flesh, fat, bone, and marrow; it imparts an aura of ojas (bright, radiant energy) to the body, and ojas is, in essence, the elemental, particulate form of cosmic shakti.

Although the physiology of this transformation is what matters in the context of martial arts training and self-development, the embodied process of metamorphosis is congruent with cosmological mythology and astrology. The underlying model within this cosmology is the flow of liquids and the dynamic interplay of dry solar heat and cool, moist, lunar fluids. The waxing and waning of the moon are conceived of as the drying up and death of the lunar king, but then his subsequent cyclical rejuvenation. Rejuvenation is regarded as a process by which cool, moist, lunar “semen” is replenished. Significantly, this cosmology defines the potential energy of contained semen, and the embodiment of semen, in terms of the negative consequences of its outward flow. In an important way the high value placed on semen/shakti in the Indian martial arts is defined in terms of the danger associated with indiscriminate sensual arousal, and one can note, in the anxious rhetoric of contemporary religious teachers, the underlying mythic symbolism of heat, waning energy, and the violent de-structiveness of sex.

Sivananda characterizes this condition in the following way: “Because the youth of today are destroying their semen, they are courting the worst disaster and are daily being condemned to hell. . . . How many of these unfortunate people lie shaking on their cots like the grievously ill? Some are suffering from heat. . . . There is no trust of God in their hearts, only lust. . . . [W]hat future do such people have? They only glow with the light of fireflies, and neither humility nor glory are found in their flickering hypocrisy” (1984, 41).

In terms of formalized religious practice, celibacy is institutionalized in the life stage of brahmacharya, in the sense of chaste discipleship. In this sense a brahmachari is not simply celibate, although certainly and primarily that, but also a novice scholar who submits himself to the absolute authority of a guru (adept master). As the first stage of the ideal life course, brahmacharya is roughly congruent with the age through which most children attend school, with marriage when a young man is in his early to mid-twenties. In the idealized scheme, a brahmachari is a high-caste Brahman boy who must learn by rote the Vedic scriptures and all of the formal ritual protocol associated with those scriptures. The concept of chastity is relevant here insofar as a boy who is able to control his desire is not distracted, better able to learn—in the sense that he has a greater capacity for memory—and also in appropriately good physical health, both strong and pure. Although brahmacharya as a life stage is associated with ritual and Vedic learning, it also has much wider pedagogical salience as a model for all forms of instruction, both explicitly spiritual, as when a person submits to the devotional teaching of a holy man, as well as more secular, as when a person learns a craft, a musical instrument, or a martial art from an accomplished teacher. It is significant that these “secular” forms of the master-disciple relationship are only secular in terms of content. The mode of instruction and the attitude of complete submission to authority and total identification with the guru that are incumbent on the disciple stem directly from the idealized Vedic model. Celibacy factors into this attitude because of the extent to which a disciple must be able to focus his whole being on the act of learning and literally embody the knowledge his guru imparts.

Hindu scriptures are replete with references to the link between sex, fertility, and mastery of power, both supernatural and natural—and the link is complex. In many instances, it is also inherently ambiguous, insofar as sex—understood as an analog for divine creation—is the source of great power, but also—understood as an instinctual, bestial, subhuman drive—is regarded as an act through which all power can be lost if it is not carefully controlled. In any case, the deity who is celibacy incarnate, most clearly manifests shakti, iconographically embodies the physiology of ojas, and translates all of this explicitly into the domain of martial arts is Lord Hanu-man, hero of the epic Ramayana. Although he is most closely associated with wrestling and is known for having performed feats of incredible strength, in fact the nature of Hanuman’s power is more complex. To begin with, Hanuman is a monkey, or the son of a nymph and a monkey, and is thought to possess the nascent attributes of his simian lineage. This is made clear in many of the myths and folktales associated with him that, in essence, depict him “monkeying around.” In one notable instance, as an infant, he flew off intent on eating the sun, manifest as the chariot of the god

Indra, thinking the golden orb was a succulent orange. Indira threw his spear and knocked Hanuman unconscious to the ground. At this, Vayu, god of the Wind and surrogate father of the young monkey, withheld his power and threatened to suffocate the world unless his son’s life was saved. At this moment, the whole pantheon of gods rallied to Hanuman’s side and bestowed on him their respective supreme powers. As a result of this, Hanuman is immortal and invincible. He also has the ability to change form and change size. He—again betraying the subhuman attributes of his lineage—is not conscious of these powers until he is made so by a suprahu-man deity, in particular his lord and master, Sri Ram.

Lord Hanuman is one of the most popular deities in the Hindu pantheon, in part because he is a deity whose primary spiritual attribute is his own devotion to Lord Ram. In other words, Hanuman provides human supplicants with a clear divine model for their own devotional practices, and, significantly, it is from these devotional practices that Hanuman is wise beyond the wisest and an expert in the use of all weapons, among many other things. From the act of sensory withdrawal and complete emotional transference, Hanuman derives his phenomenal strength, skill, and wisdom. For the vast majority of supplicants, devotionalism is an end in itself. And, given the metaphorical link between celibacy and fertility, newly married women often pray to Hanuman to bless them with the birth of a son. However, Hanuman is most clearly recognized as the patron deity of akharas (gymnasiums), and in this context he is an explicit link between the domain of spiritual, cosmic shakti, celibacy and the embodiment of shakti, and the performance of martial arts. A shrine dedicated to Lord Hanuman is found in almost all gymnasiums, and in addition to performing rituals of propitiation and offering prayers to him, men who engage in martial arts training attribute their skill and strength to the extent of their ability to embody celibacy and thereby become in their relationship to Hanuman as Hanuman is to Lord Ram.

Celibacy is an integral feature of the martial arts in India, and in addition to being closely linked to Hanuman, it is an important aspect of two other forms of practice that together constitute one of the central coordinates around which Hindu doctrine has been constructed: sannyas (world renunciation) and yoga (the union of the individual self with the cosmic soul). Technically, a sannyasi is a person who has moved through each of the first three stages of the ideal life course—celibate discipleship, ritual-performing family man, and forest-dwelling monk—and has gone in search of moksha (final liberation from the cycle of rebirth). As a sannyasi, a person must have no possessions, no family, no home, and no desire for worldly things. After performing the rites to his own funeral—thereby symbolically dying—he secludes himself to perform tapas (austerities), and from these austerities is thought to develop phenomenal powers before achieving final liberation. Significantly, the powers that a sannyasi comes to possess through the performance of austerities are embodied, even though the final realization of liberation entails a complete dissolution of the body. In popular imagination, sannyasis can tell the future, read minds, and perform other miracles. Often the act of performing intense austerities is said to generate tremendous heat, referred to commonly as tapas. The heat of tapas is closely linked both conceptually as well as in a theory of physiology associated with the retention of semen. In many respects, therefore, the sannyasi is an ascetic analog of the divine ape, Hanuman, and practitioners of the martial arts in India draw on both models to define the nature and extent of their own strength and skill.

Interestingly, recent scholarship has shown that sannyasis were, in all likelihood, themselves practitioners of various martial arts. Although past scholarship has tended to emphasize the asocial, ascetic, and purely cognitive features of sannyas, it is clear that at various times in the history of South Asia, groups of sannyasis (known tellingly as akharas, a term that can mean either “gymnasium” or “ascetic order, celibacy, and yoga”) have used their power to develop specific fighting skills. These so-called fighting ascetics were retained by merchants, landlords, and regional potentates to defend or extend their various interests. In some instances sannyasis of this kind amassed significant amounts of wealth and exercised considerable political power. A recent permutation of this practice is manifest in present-day Ayodhya, a prominent religious city in north India, where the heads of various akharas have tremendous political clout, as well as in the articulation of aggressive, chauvinistic, communal Hinduism, wherein the powerful sannyasi is seen as the heroic embodiment of idealized Hindu masculinity.

In contrast to East Asia, where the ascetic practices associated with Daoism produced the archetypal martial arts, there is very little known about how the fighting ascetics of India refined their skill. However, it is clear that yoga as a form of rigorous self-discipline is an integral part of ascetic practice, and that yoga makes reference to a theory of subtle physiology that translates very well into the language and practice of martial arts, even though in recent history it has come to be regarded, by most practitioners, as the antithesis of these arts. Although yoga is often thought of as being cerebral, supremely metaphysical, and concerned with such ephemeral concepts as the transmigration of the soul and the dissolution of consciousness, many of the basic or preliminary steps in yoga entail clearly defined codes of conduct, comprehensive ethical standards, and detailed prescriptions for personal “moral hygiene,” as well as the more commonly known methods of asanas (physical postures) and pranayama (breathing exercises). These preliminary steps of yoga are designed to build up a practitioner’s overall strength such that he or she is able to withstand the force of transcendental consciousness.

Pranayama is of particular importance. In yogic physiology, a person is said to be composed of a series of body-sheaths, which range across the spectrum from the gross anatomy of elemental metamorphosis at one extreme to the subtle, astral aura of the soul at the other. Pran (vital breath) is said to pervade all of these sheaths, and there is a close relationship, both metaphorical and metonymical, between air as breath and the vital, subtle breath of pran. Not only are they alike figuratively, but one has come to stand for the other. Pran, as cognate with and as related to shakti, is thought to be the very energy of life, and yogic breathing exercises are conceived of as the means by which one can purify, concentrate, and channel this energy. In this regard, a theory of pranic flow through the nadis (subtle channels or meridians of the body) explains how cosmic energy is mi-crocosmically embodied within the individual body.

Most closely associated with the esoteric, self-consciously mystical teachings of Tantrism, nadi physiology is integral to yoga in general. Although subtle and thereby imperceptible to the gross senses, nadis pervade the body in much the same way as do veins, arteries, and capillaries, on the one hand, and nerves on the other. Of the hundreds of thousands of nadis, three are of primary importance in yoga, the axial sushumna, which runs up the center of the trunk from anus to crown, and the ida and pingla, which both start from the anus and intersect the sushumna at key points as they crisscross from left to right and right to left respectively. These key points are referred to as chakra centers, which, among many other things, reflect the energy of pran as the disarticulated pran flowing through all three conduits comes together. The ultimate goal of pranayama is to cleanse the channels, purify pran, and then channel it exclusively through the sushumna nadi such that it penetrates consciousness and yokes—or harnesses as yogic imagery would have it (even though yoke and yoga have a common etymol-ogy)—the individual soul to the cosmic spirit of the universe.

In this regard asanas are, technically, “seats” rather than postures, and are designed to anchor, or root, the body in space, thus explicitly facilitating the practice of “yoking.” The classical padamasana (lotus seat) as well as similar cross-legged seated positions such as sukhasana and sid-dhasana are particularly important, insofar as they enable a person to sit motionless for many hours and also stabilize the subtle body. Thus, before a person engages in the four “higher” stages of yogic meditation, he or she must master these “empowering” ways of sitting. However, apart from these “seats-in-fact,” the relative importance to yoga as a whole of the more “vigorous” stretching, bending, and flexing asanas is unclear, since many of the classical, authoritative works on the subject, such as the Yoga

Sutra of Patanjali, give scant mention to the subject of this kind of yoga. However, there is no doubt that asanas have become a highly developed form of physical self development, and this development can be traced back to the medieval period of South Asian history and the structured asceticism of the Kanpatha Sect of sannyasis. Although these ascetics were concerned with the embodiment of power, it is difficult to imagine that asanas were, in and of themselves, a form of martial art, given that they do not entail movement as such. However, there is the intriguing possibility that yogic asanas, linked together through a series of connective movements, might have constituted a more active style of martial self-development along the lines of taijiquan (tai chi ch’uan) (cf. Sjoman 1996). Regardless, it is clear that in contemporary practice, asanas are conceived of as a form of physical fitness training for both the subtle and gross bodies, with primary attention given to the locus points at which these bodies tend to affect one another most directly: the internal organ/chakra nexus, the spine/sushumna axes, and, to a lesser extent, the joint/nerve/nadi/tendon complex.

In essence yoga is a method for achieving siddha (perfection) in the whole body-mind complex. Although perfection is meant to lead to a state of complete nothingness, a person who comes close to perfection is able to perform supernatural feats. In the canonical literature of Hinduism, as well as in more popular folk genres, yogis often figure as characters who use their power to perform miracles or, as is often the case when they are disturbed from deep meditation, to curse and otherwise punish those who are less than perfect. Thus, in a very concrete sense, the power associated with yoga is regarded as having an outward orientation and is not only directed inward toward the self and away from others or society at large. Although the power of a yogi can often be destructive, in either a defensive or offensive mode, an adept yogi can embody near perfection, such that the aura of his personality has a positive effect on those with whom he comes in contact. Although this “personality” is not physiological per se, nor is it “martial” in any meaningful sense, the way in which a yogi’s embodied con-sciousness—his spirituality or the subtle aura of his religious persona—can factor into problematic social relationships should be understood as an extension of the logic behind more explicitly martial arts.