Chinese historical records and other writings over the centuries reveal that the martial arts were practiced among all elements of society, including religious groups. However, there is little evidence that there was any significant religious influence over the martial arts or that they were a product of religious experience. On the contrary, they were the product of a clan society intent on protecting group interests and of the existence of widespread warfare among contending states during China’s formative period.

Nevertheless, there seems to be a strong current in modern martial arts circles, especially outside China, to associate the martial arts with religion, mainly Zen (in Japanese; Chan in Chinese) Buddhism, religious as opposed to philosophical Daoism (Taoism), and various heterodox groups such as the White Lotus and Eight Trigrams sects. That individuals from all these groups practiced the martial arts is undeniable. That some individuals in all these groups may have tried to integrate these arts into their belief systems is almost certain.

However, that these arts are inseparable from a religious or spiritual context is simply unfounded. On the other hand, martial arts concepts are clearly based on a Daoist philosophical worldview, and this includes psychological as well as physical aspects. This worldview predated the establishment of popular religious Daoism and strongly influenced later Confucian and Buddhist, especially Chan (Zen), thought. It appears that many individuals have mistaken this worldview as necessarily being religious or spiritual. Because of the omnipresence of Daoist thought in Chinese culture and society, the psychophysiological nature of martial arts practices, and the dearth of serious, factual writing on the subject, it is perhaps understandable that misunderstandings have arisen in modern times concerning the nature and origins of the martial arts and their place in society. Added to these factors is the disproportionate amount of attention paid to the role of Shaolin Monastery and, by association, the perceived connection between Chan (or Zen) Buddhism and the martial arts.

The martial arts probably more often entered monasteries and temples from the population at large rather than vice versa. The residents of Buddhist monasteries and Daoist temples and the followers of heterodox religious groups practiced martial arts to protect themselves. Along with forms of qigong (cultivation of qi [chi; vital energy]), the martial arts also served as a form of mental and physical cultivation for those so inclined.

The population in Buddhist monasteries and Daoist temples comprised a mix of regular residents and transients, some of whom were individuals seeking to escape the law. For instance, one Ming period official describes Shaolin monastery as a hideout for rebels, including White Lotus sect members seeking to escape the authorities during times of unrest. Two of the main characters in the early Ming period popular novel, Outlaws of the Marsh (also known as Water Margin or All Men Are Brothers), known for their martial prowess, are in this category. One, Lu Zhisheng, a carousing “monk,” enters a monastery to escape punishment for killing an official. The other, Wu Song, disguises himself as a wandering monk to avoid detection.

The Martial Arts and Buddhism

Buddhism’s earliest adherents in China were the rich and aristocratic (including a significant number of high-level military patrons) and, under the Northern Wei dynasty (a.d. 386-534), it was adopted as the state religion, with an organized church and bureaucratic structure, and, as such, it was beholden to the state. Monasteries had large landholdings and, like secular owners of landed estates, organized to protect their wealth with manpower from within their ranks. These men came from the local citizenry, some of whom may have been in the military or have learned the martial arts in some other way.

Young acolytes also let off steam with wrestling and acrobatics. For instance, an apocryphal story of one Shaolin monk, Zhou Chan, who lived during the Northern Qi period (a.d. 550-577), relates how his compatriots bullied him at first because of his frail appearance. According to the story, he ran into one of the halls, bolted the doors shut, threw himself at the feet of a guardian image, and prayed for six days that he be given the ability to defend himself. On the sixth day, the guardian image appeared with a large bowl full of tendons and told Zhou Chan to eat them if he desired strength. He reluctantly ate them (good Buddhists are supposed to be vegetarians) and returned to his compatriots, who began as before to harass him. They were surprised, however, when they felt the incredible strength of his arms. He then ran several hundred paces along the wall of the large hall, leapt so high his head reached the ceiling beams, lifted unbelievably heavy loads, and put on a display of strength and agility that even frightened inanimate objects into moving.

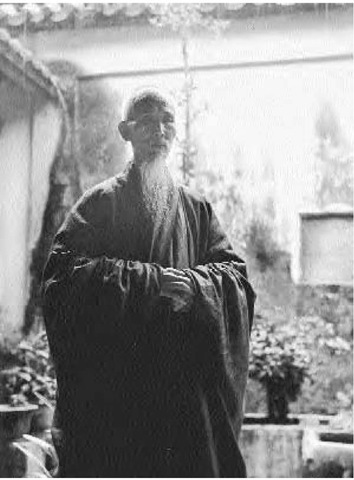

A Chinese Daoist monk, ca. 1955.

The exercise value of martial arts practice as part of daily routine was recognized and described by the monk Dao Xuan (a.d. 596-667), in his Further Biographies of Eminent Monks. His description, however, is not of monks but of a devout Buddhist Indian prince, of warrior caste, who practiced after dinner.

The monasteries were powerful institutions—sometimes considered dangerously so. In a persecution in a.d. 446, Emperor Taiwu is reported to have personally led a raid on monasteries in and around Changan (now Xian), which uncovered various activities such as moonshine production, weapons caches, and even prostitution. Emperor Xiaowu (532-534) is recorded as having a contingent of Buddhist monks fight for him during his retreat as the dynasty collapsed.

Shaolin Monastery, established in a.d. 495 by the Indian monk known in Chinese as Ba To, was just one of many monasteries at the time, but its location, historical circumstances, and possibly the disciplined yet individualistic nature of the Zen (Chan) Buddhism that was introduced there resulted in its subsequent fame as a center for martial arts. Built at the foot of Mount Song in today’s Henan province, it was close to China’s social, political, and geomantic center at that time. As early as 140-87 b.c., Mount Song was known as the central among China’s five sacred mountains, and it has been a popular destination for pilgrims over the centuries.

Shaolin Monastery’s singularly strong association with fighting arts can be readily understood in terms of its exposed location between the ancient capitals of Loyang and Kaifeng, which made it extremely vulnerable to the ebb and flow of war and social upheaval, requiring the monks to maintain a self-defense capability.

As a group, the fighting monks of Shaolin Monastery first appear in the midst of the confusion surrounding the collapse of the Sui dynasty and the rise of Tang (a.d. 605-618). Two incidents (both recorded on a stele dated 728) laid the foundation for the fighting fame of the Shaolin monks. In the first incident, the monks managed to repulse an attack by marauding bandits, but the monastery buildings suffered considerable damage in the process. In the second, and most famous incident, the first Tang emperor’s son, Prince Qin (Li Shimin or Emperor Taizong, who ruled between 627-649) requested the heads of the monastery to provide manpower and join with other local forces to fight Wang Shichong, who had established himself in the area in opposition to Tang rule. With Wang based near the monastery and probably eyeing it for its strategic location, the monks readily joined forces against him, helped capture his nephew, and assisted in his defeat. As a result, the monastery was issued an imperial letter of commendation and a large millstone, and ceded land comprising the Baigu Estate. Thirteen of the monks were commended by name, one of whom, Tanzong, was designated general-in-chief. Research has revealed that the primary motive for erecting the stele that records this information was to protect monastery property gains resulting from this incident. And, indeed, with imperial favor, Shaolin Monastery retained its properties while other monasteries in the area were divested of much of theirs. The monks were recognized for military merit. As for the actual martial arts skills of the thirteen monks, the record fails to provide any specifics. Later writers have assumed such skills, some even venturing so far as to refer to them as the Thirteen Staff Fighting Monks of Shaolin Monastery. The monks’ main contribution was more likely in providing the leadership necessary to direct local forces. Martial arts skills were actually fairly widespread in the villages and throughout the countryside, from whence they entered the monasteries.

For nearly 900 years following the deeds of the thirteen monks, there is not a single reference to martial arts practice in Shaolin Monastery. Not that martial arts were not practiced there, just that, if they were, they were likely nothing out of the ordinary—at most a security force from the monastic ranks. During the same period, there are sparsely scattered references to individual monks, not necessarily from Shaolin Monastery, who were involved in military activities. Two of these appear during the Song period when China was invaded by Jurched tribes, who founded the Jin dynasty (1122-1234). One, Zhen Bao, on orders from Emperor Qin Zong (1126), formed an army and fought to the death defending the monasteries on Mount Wutai in Shanxi. Another, Wan An, is recorded as having said, “In time of peril I perform as a general, when peace is restored I become a monk again.” In both these cases, one can see that the leadership role, as with the incident involving the thirteen monks of Shaolin Monastery, was of primary importance. Monks might provide disciplined leadership when needed in perilous times. In addition, the larger monasteries such as Shaolin and those on Mount Wutai were, more often than not, the objects of imperial patronage, and one of their roles would have been to pray for national peace and prosperity, and to support political authority.

The high tide of Shaolin Monastery’s martial arts fame came in the mid-sixteenth century at a time of serious disruption in China’s coastal provinces as a result of large-scale Japanese pirate operations. Two hundred years earlier, in 1368, the monastery had suffered a major catastrophe when over half of its buildings were burnt to the ground and its residents were temporarily scattered to neighboring provinces in the wake of the Red Turban uprising against Mongol rule. This traumatic experience apparently inspired the returning monks to take their security duties and martial arts practice more seriously from then on. In 1517, well after the monastery was restored, a stone tablet was erected that ignored the story of the monastery’s destruction. It claimed that the monastery had actually been spared because a monk with kitchen duties had miraculously transformed himself into a fearful giant with a fire poker for his staff, who ran out and scared off the Red Turbans. Regardless of the mythical aspects of this story, which may have been designed to remind the monks of their responsibilities as well as warn away transgressors, the monks actually had become known for their staff-fighting prowess, and a form of staff fighting was named after the monastery.

Observations by visitors to the monastery during the sixteenth century reveal that popular forms of boxing, such as Monkey Boxing, were also practiced by some of the monks, but none of these forms were named after the monastery. Cheng Zongyou, who claimed to have spent a decade studying staff fighting there, tells us that some of the residents were concentrating on boxing to try to bring it up to the standards of the famed Shaolin Staff. In any case, during the mid-Ming, the monks had built up their reputation as martial artists, and they responded to a call for volunteers to fight Japanese pirates on the coast. Their everlasting fame as Shaolin Monk Soldiers resulted from their participation in a campaign in the vicinity of Shanghai, where a monk named Yue Kong led a group of thirty monks armed with iron staves. They were instrumental in the ultimate victory against the pirates, but sacrificed themselves to a man in the process.

Ironically, most of Shaolin Monastery and Zen Buddhism’s actual association or lack of association with the martial arts has been obscured by early nineteenth-century secret society activity and subsequent embellishments in popular novels such as Emperor Qian Long Visits the South (by an unknown author) and Liu E’s Travels of Lao-ts’an. The Heaven and Earth Society (also known as the Triads or Hong League) associated themselves with the monastery’s patriotic fame as a recruiting gimmick. Concocting a story to suit their needs, however, the society members traced their origins to a fictitious Shaolin Monastery said to have been located in Fujian province, where the society had its beginnings in the 1760s. Around 1907, Liu E, in his short but powerful critique of social conditions in late Qing China, refers to Chinese boxing originating with Bodhidharma, the legendary patriarch of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, who is said to have spent nine years meditating facing a rock in the hills above Shaolin Monastery. Finally, on the eve of the Revolution of 1911, the contents of a probable secret society hongquan (Hong fist) boxing manual, Secrets of Shaolin Boxing Methods, were published in Shanghai. This manual, more than any other single publication, became a major source for much of the misinformation concerning the association of Chinese boxing with Shaolin Monastery and Buddhism.

The Martial Arts and Popular Religious Daoism

While the Chinese martial arts are based on the philosophical Daoist worldview, there is little evidence to show a serious connection to popular religious Daoism, except in that some martial artists must certainly have incorporated Daoist internal cultivation or qigong-type physical regimens into their martial arts practices. However, these regimens were not the unique preserve of Daoists, or any particular religious group for that matter. The Daoist intellectual and onetime military official, Ge Hong (290-370), practiced martial arts in his younger days and concentrated on Daoist hygiene methods in his later years. He did not treat the martial arts as Daoist activities. During the Tang dynasty, one old Buddhist monk in his eighties named Yuan Jing from a monastery in the vicinity of Shaolin Monastery (but not necessarily a Shaolin monk as has often been assumed) involved himself in a rebellion.

He had apparently conditioned his body to the point that attempts by his captors to break his neck failed, so he cursed them and challenged them to break his legs. Failing this as well, they hacked him to death. The famous artist Zheng Banqiao (1693-1765) records a similar case where a friend of his learned the secret of “practicing qi and directing the spirit” from a Shaolin monk (Wu and Liu 1982, 376). Zheng claimed his friend practiced for several years to the point where his whole body became hard as steel and, wherever he focused his qi, neither knife nor ax could wound him. At the extreme superstitious end of the spectrum were the practices of some of the Boxers in the uprising of 1900, who went into trances and mumbled incantations believed to turn them into eight-day martial arts wonders and immunize them from the effects of weapons.

The earliest and single most important document to hint at a martial arts association with popular Daoism is Ming patriot Huang Zongxi’s Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan (1669). Huang claimed that Shaolin was famous for its boxing, which emphasized attacking an opponent, but that there was also an Internal School that stressed restraint to counter movement. According to Huang, this school’s patriarch was a Daoist hygiene practitioner from Mount Wudang named Zhang Sanfeng. In the political context of the times, the opposing boxing schools in the epitaph can be viewed as symbolizing Han Chinese (indigenous Daoism represented by Zhang Sanfeng and Mount Wudang) opposition to Manchu (foreign Buddhism represented by Shaolin Monastery) rule. In other words, the epitaph is actually a political statement, not a serious discourse on religion or opposing boxing schools. At the beginning of the twentieth century some boxing teachers attempted to categorize taijiquan (tai chi ch’uan), xingyiquan (hsing i ch’uan), and baguazhang (pa kua ch’uan) as Internal School styles and to identify taijiquan with Zhang Sanfeng and Daoism. Around the same time, and persisting to the present day, a number of newer martial arts forms have come to be identified with Mount Wudang and Daoism.

Conclusion

As can be seen from the foregoing narrative, the connection between the Chinese martial arts and religion is artificial at best. Individuals from all walks of life and all beliefs, including China’s Muslims and other minorities, practiced martial arts of one form or another for individual and collective defense—but the martial arts were primarily secular, not religious, activities. Attribution of a religious mystique to the Chinese martial arts is, for the most part, a very recent phenomenon based on misunderstandings of the past, but reflecting needs of the present.