Very early, the Chinese observed the characteristics of their natural environment, including the wildlife and, as early as 300 b.c., there is evidence in the writings of Zhuangzi (Chuang-tzu) that they were imitating animal movements (birds and bears) as a form of exercise. The doctor Hua Tuo is said to have developed the Five Animal exercises (tiger, deer, bear, ape, and bird) around a.d. 100, and it is very easy to imagine how animal characteristics were adapted to fighting techniques. Another view is that at least some animal forms may hark back to a distant totemic past that still occupies a place in the Chinese psyche. This totemic influence is difficult if not impossible to trace in majority Han Chinese boxing styles; however, it can be seen in the combination of martial arts and dance practiced by some of China’s many national minorities. Cheng Dali, in his Chinese Martial Arts: History and Culture, points to Frog Boxing, practiced by the Zhuang Nationality of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, as an example, the frog being considered their protector against both natural and man-made disasters.

The monkey or ape, with its combination of human characteristics and superhuman physical skills, has long been associated with martial arts. The most notable early reference is to the ape in the story of the Maiden of Yue (ca. 465 b.c.). In this story, an old man transforms himself into an ape who tests the swordsmanship of the Maiden of Yue before she is selected by the king of Yue to train his troops. Perhaps better known are the exploits of the monkey with the magic staff in the Ming novel Journey to the West (sixteenth century). He fights his way through a host of demons to protect the monk, Xuan Zang, during his pilgrimage to India and return to China with Buddhist scriptures.

Monkey Boxing was among the prominent styles listed by General Qi Jiguang in his New topic of Effective Discipline (ca. 1561), and Wang Shixing (1547-1598) was impressed with a Monkey Boxer he observed practicing at Shaolin Monastery (Tang 1930). General Qi also mentions the Eagle Claw Style.

During the Qing period (1644-1911), the Praying Mantis Style appeared in Shandong province, and numerous other animal routines became associated with major styles of boxing, such as the five animals of Hong-quan (dragon, tiger, leopard, snake, crane), sometimes seen as synonymous with Shaolin Boxing; the twelve animals (tiger, horse, eagle, snake, dragon, hawk, swallow, cock, monkey, Komodo dragon-like lizard, tai, and bear) of Shanxi-style xingyi boxing; and the ten animals of Henan-style xingyi boxing (tiger, horse, eagle, snake, dragon, hawk, swallow, cock, monkey, and cat). These styles and forms represent a human attempt to mimic specific practical animal fighting and maneuvering techniques. Of course, the dragon is a mythical beast, so this form is based on the Chinese vision of the dragon’s undulating movement and the way it seizes with its claws—a pull-down technique. The tai is an apparently extinct bird whose circular wing movements suggest a deflecting/defensive form. Some of the so-called animal forms could be categorized in other ways. For instance, some of the animal techniques in xingyi boxing could be subsumed under the basic Five Element forms (crushing, splitting, drilling, pounding, and crossing). In addition to the actual animal forms, many Chinese boxing forms have flowery titles such as “Jade Maiden Thrusts the Shuttle,” “Step Back and Straddle the Tiger,” and “White Ape Offers Fruit.” These are merely traditional images, familiar to most Chinese, used as mnemonic devices to assist when practicing routines.

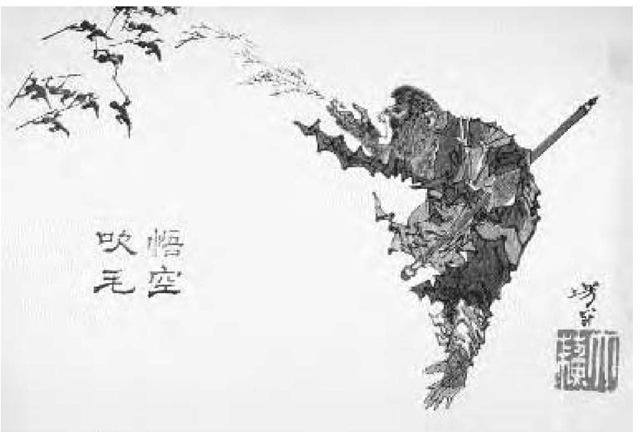

The magic monkey Songoku from a Chinese fable creates an army by plucking out his fur and blowing it into the air—each hair becomes a monkey-warrior.

The pure animal styles of boxing exude a certain amount of individual showmanship in the same way as does the Drunken Style, which is said to have evolved from an ancient dance, and some other particularly acrobatic styles. These are all basically popular folk styles as opposed to no-frills, military hand-to-hand combat styles, whose techniques can be seen subsumed in some existing styles, but whose separate identity has essentially been lost in modern times.