Tooth Form and Jaw Movements

In general terms, the primates are bunodont and relatively isognathous and therefore have limited lateral jaw movement. Bunodont refers to tooth-bearing conical cusps. Isog-nathous means equally jawed; anisognathus means unequally jawed. Humans are not perfectly isognathous (i.e., the maxillary arch overlaps horizontally the mandibular arch). The shape of the glenoid (mandibular) fossae (see Figure 15-1) is correlated also with tooth form and jaw movements. A number of living and extinct species demonstrate a number of dental forms, from the bunodont to the selenodont (i.e., molars with crescent-shaped cusps) types. Each type is accompanied by an increased mobility of the mandible in a lateral direction and increased anisognathism. When the incisal point is viewed from the front during mastication, the mandible moves up and down without lateral deviation in dogs, cats, pigs, and all other animals with bunodont articulations. Lateral movement increases in a number of animals to the extreme lateral excursions seen in the giraffe, camel, and ox. In relation to the latter type of movement, it has been proposed that where the condyle is greatly elongated transversely and very flat, great lateral movement occurs during mastication, associated with selenodont molars, and a great degree of anisognathism. Also of interest for the gnathologist is the putative correlation between the directions of the ridges and grooves and a radius drawn to the center of the glenoid fossa.

It has been suggested that the simplest type of jaw movement is opening and closing without lateral excursion and coexistent with the simple bunodont molar. With increasing complexity of movement, an apparent increase in the complexity of enamel folding, ridges, and crests occurs, which might be consistent with the hypothesis of the mechanical genesis of tooth forms.31 Correlations between the forms of the teeth, joints, muscles, skull, bones, and jaw movement appear to be consistent with the functions of each species.

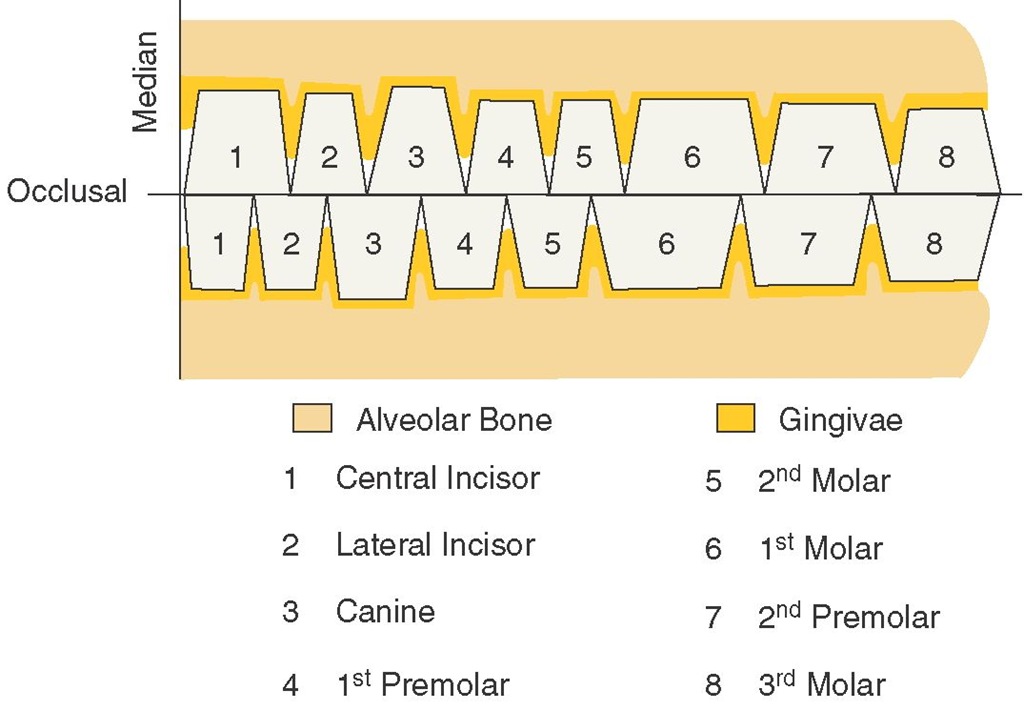

Figure 4-15 Schematic drawing of facial (labial and buccal) aspects of the teeth only, illustrating the teeth as trapezoids of various dimensions. Note the relations of each tooth to its opposing tooth or teeth in the opposite arch. Each tooth has two antagonists except number 1 below and number 8 above.

GEOMETRIES OF CROWN OUTLINES

In a general way, all aspects of each tooth crown except the incisal or occlusal aspects may be outlined schematically within one of three geometric figures: a triangle, trapezoid, or rhomboid. To one unfamiliar with dental anatomy, it may seem an exaggeration to say that curved outlines of tooth crowns can be included within geometric figures. Nevertheless, it seems very plausible to consider fundamental outlines schematically to assist in visualization (see Figures 4-15 and 4-16).

Facial and Lingual Aspects of All Teeth

The outlines of the facial and lingual aspects of all the teeth may be represented by trapezoids of various dimensions. The shortest of the uneven sides represent the bases of the crowns at the cervices, and the longest of the uneven sides represent the working surfaces, or the incisal and occlusal surfaces, the line made through the points of contact of neighboring teeth in the same arch (Figure 4-15). Disregarding the overlap of anterior teeth and the cusp forms of the cusped teeth in the schematic drawing, the fundamental plan governing the form and arrangement of the teeth from this aspect seems apparent.

The occlusal line that forms the longest uneven side of each of the trapezoids represents the approximate point at which the opposing teeth come together when the jaw is closed in the intercuspal position or centric occlusion. The viewer must not become confused at this point and think that all of each tooth actually makes contact at the occlusal level. The illustration is made to help in visualizing the fundamental shape of the teeth from the labial and buccal aspects (Figure 4-16).

This arrangement brings out the following fundamentals of form:

Figure 4-16 Outlines of crown forms within geometric outlines—triangles, trapezoids, and rhomboids. The upper figure in each square represents a maxillary tooth, the lower figure a mandibular tooth. Note that the trapezoidal outline does not include the cusp form of posteriors actually. It does include the crowns from cervix to contact point or cervix to marginal ridge, however. This schematic drawing is intended to emphasize certain fundamentals. A, Anterior teeth, mesial or distal (triangle). B, Anterior teeth, labial or lingual (trapezoid). C, Premolars, buccal or lingual (trapezoid). D, Molars, buccal or lingual (trapezoid). E, Premolars, mesial or distal (rhomboid). F, Molars, mesial or distal (rhomboid).

1. Interproximal spaces may accommodate interproximal tissue.

2. Spacing between the roots of one tooth and those of another allows sufficient bone tissue for investment for the teeth and sufficient supporting structures to be consistent with the length, form, nutrition, and function of the adjacent teeth.

3. Each tooth crown in the dental arches must be in contact at some point with an adjacent tooth or teeth to help protect the interproximal gingival tissue from trauma during mastication. The contact of one tooth with another in the arch tends to ensure mutual support and occlusal stability.

4. Each tooth in each dental arch has two antagonists in the opposing arch except the mandibular central incisor and the maxillary third molar. In the event of loss of any tooth, this arrangement tends to prevent extrusion of antagonists and helps stabilize the remaining teeth.

MESIAL AND DISTAL ASPECTS OF THE ANTERIOR TEETH

The mesial and distal aspects of the anterior teeth—central incisors, lateral incisors, and canines, maxillary and man-dibular—may be included within triangles. The base of the triangle is represented by the cervical portion of the crown and the apex by the incisal ridge (see Figure 4-16, A). The fundamentals portrayed here are as follows:

1. A wide base to the crown for strength

2. Tapered outlines (labially and lingually) narrowing down to a relatively thin ridge, which facilitates the penetration of food material

MESIAL AND DISTAL ASPECTS OF THE MAXILLARY POSTERIOR TEETH

The outlines of the mesial and distal aspects of all maxillary posterior teeth (premolars and molars) can be included within trapezoidal figures. Naturally, the uneven sides of the premolar figures are shorter than those of the molars (see Figure 4-16, E and F). Notice that in this instance the trapezoidal figures show the longest uneven side representing the base of the crown instead of the occlusal line, as was the case in showing the same teeth from the buccal or lingual view. In other words, the schematic outline used to represent the buccal aspect of premolars or molars is turned upside down to represent the mesial or distal aspects of the same teeth. Figure 4-16 compares maxillary parts C and D with E and F

The fundamental considerations to be observed when reviewing the mesial or distal aspects of maxillary posterior teeth are as follows:

1. Because the occlusal surface is constricted, the tooth can be forced into food material more easily.

2. If the occlusal surface were as wide as the base of the crown, the additional chewing surface would multiply the forces of mastication.

It has been found necessary to emphasize the fundamental outlines of these aspects through the medium of schematic drawings, because the correct anatomy is overlooked so often. The tendency is to take for granted that the tooth crowns are narrowest at the cervix from all angles, which is not true. The measurement of the cervical portion of a posterior tooth is smaller than that of the occlusal portion when viewed from buccal or lingual aspects only; when it is observed from the mesial or distal aspects, the comparison is just the reverse; the occlusal surface tapers from the wide root base.

MESIAL AND DISTAL ASPECTS OF THE MANDIBULAR POSTERIOR TEETH

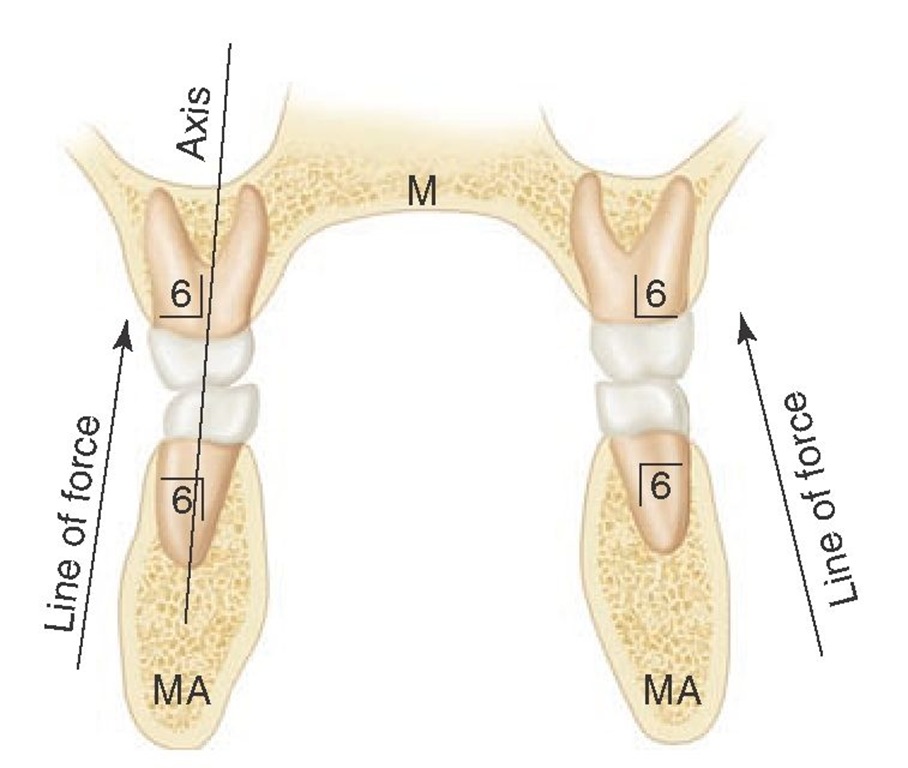

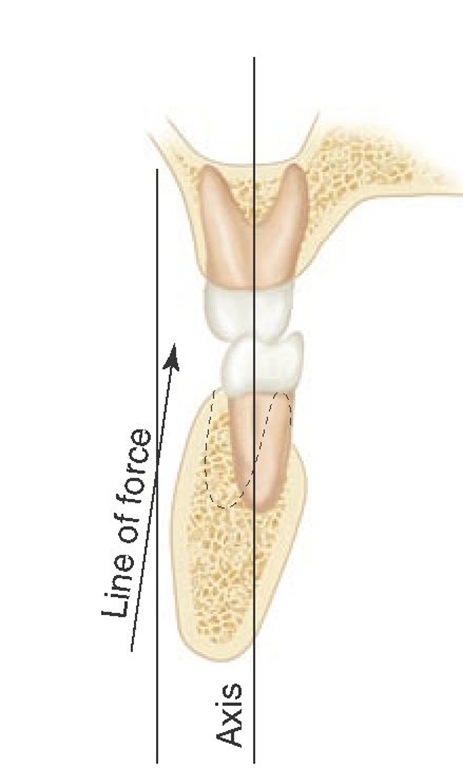

Finally, the mandibular posterior teeth, when approached from the mesial or distal aspects, are somewhat rhomboidal in outline (see Figure 4-16, E and F). The occlusal surfaces are constricted in comparison with the bases, which is similar to the maxillary posterior teeth. The rhomboidal outline inclines the crowns lingual to the root bases, which brings the cusps into proper occlusion with the cusps of their maxillary opponents. At the same time, the axes of crowns and roots of the teeth of both jaws are kept parallel (Figures 4-17 and 4-18). If the mandibular posterior crowns were to be set on their roots in the same relation of crown to root as that of the maxillary posterior teeth, the cusps would clash with one another. This would not allow the intercuspal relations necessary for proper function.

Figure 4-17 Schematic representation of clinical principle of making restorations and implants consistent with directing lines of forces parallel with long axes of the teeth. M, Maxilla; MA, mandible. Teeth numbered using Zsigmondy/Palmer notation.

Figure 4-18 Schematic representation of line of forces being incorrectly directed tangentially to the long axis of the teeth. An acceptable clinical method to determine force vectors has yet to be established.

Summary of Schematic Outlines

Outlines of the tooth crowns, when viewed from the labial or buccal, lingual, mesial, and distal aspects, are described in a general way by triangles, trapezoids, or rhomboids (Figure 4-16, A through F).

TRIANGLES

Six anterior teeth, maxillary and mandibular

A. Mesial aspect

B. Distal aspect

TRAPEZOIDS

I. Trapezoid with longest uneven side toward occlusal or incisal surface

A. All anterior teeth, maxillary and mandibular

1. Labial aspect

2. Lingual aspect

B. All posterior teeth

1. Buccal aspect

2. Lingual aspect

II. Trapezoid with shortest uneven side toward occlusal surface

A. All maxillary posterior teeth

1. Mesial aspect

2. Distal aspect

RHOMBOIDS

All mandibular posterior teeth

A. Mesial aspect

B. Distal aspect