Division into Thirds, Line Angles, and Point Angles

For purposes of description, the crowns and roots of teeth have been divided into thirds, and junctions of the crown surfaces are described as line angles and point angles. Actually, there are no angles or points or plane surfaces on the teeth anywhere except those that appear from wear (e.g., attrition, abrasion) or from accidental fracture. Line angle and point angle are used only as descriptive terms to indicate a location.

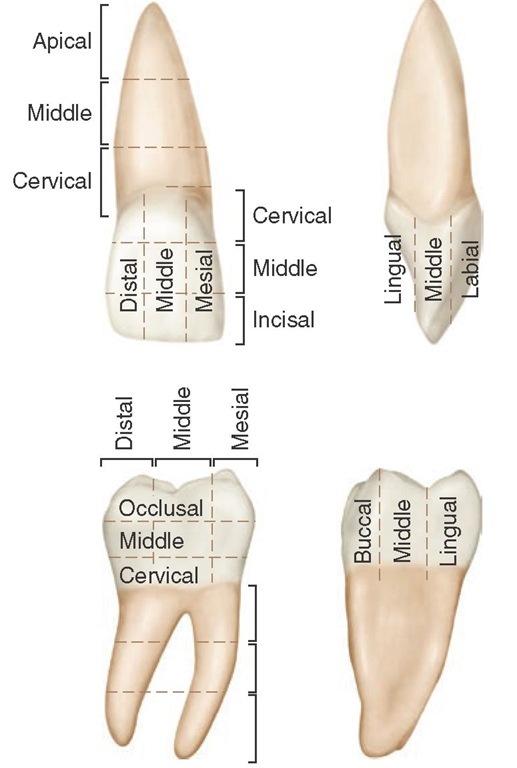

Figure 1-13 Division into thirds.

When the surfaces of the crown and root portions are divided into thirds, these thirds are named according to their location. Looking at the tooth from the labial or buccal aspect, we see that the crown and root may be divided into thirds from the incisal or occlusal surface of the crown to the apex of the root (Figure 1-13). The crown is divided into an incisal or occlusal third, a middle third, and a cervical third. The root is divided into a cervical third, a middle third, and an apical third.

The crown may be divided into thirds in three directions: inciso- or occlusocervically, mesiodistally, or labio- or buc-colingually. Mesiodistally, it is divided into the mesial, middle, and distal thirds. Labio- or buccolingually it is divided into labial or buccal, middle, and lingual thirds. Each of the five surfaces of a crown may be so divided. There will be one middle third and two other thirds, which are named according to their location, for example, cervical, occlusal, mesial, lingual.

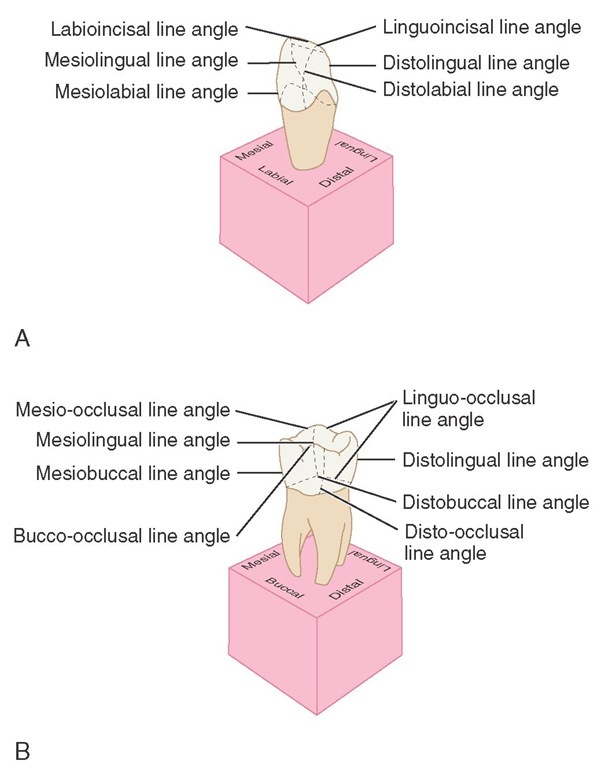

A line angle is formed by the junction of two surfaces and derives its name from the combination of the two surfaces that join. For instance, on an anterior tooth, the junction of the mesial and labial surfaces is called the mesiolabial line angle.

The line angles of the anterior teeth (Figure 1-14, A) are as follows:

|

mesiolabial |

distolingual |

|

distolabial |

labioincisal |

|

mesiolingual |

linguoincisal |

Figure 1-14 Line angles. A, Anterior teeth. B, Posterior teeth.

Because the mesial and distal incisal angles of anterior teeth are rounded, mesioincisal line angles and distoincisal line angles are usually considered nonexistent. They are spoken of as mesial and distal incisal angles only.

The line angles of the posterior teeth (Figure 1-14, B) are as follows:

|

mesiobuccal |

distolingual |

bucco-occlusal |

|

distobuccal |

mesio-occlusal |

linguo-occlusal |

|

mesiolingual |

disto-occlusal |

A point angle is formed by the junction of three surfaces. The point angle also derives its name from the combination of the names of the surfaces forming it. For example, the junction of the mesial, buccal, and occlusal surfaces of a molar is called the mesiobucco-occlusal point angle.

The point angles of the anterior teeth are (Figure 1-15, A):

|

mesiolabioincisal |

mesiolinguoincisal |

|

distolabioincisal |

distolinguoincisal |

The point angles of the posterior teeth are (Figure 1-15, B):

|

mesiobucco-occlusal |

mesiolinguo-occlusal |

|

distobucco-occlusal |

distolinguo-occlusal |

Figure 1-15 A, Point angles on anterior teeth. B, Point angles on posterior teeth.

Tooth Drawing and Carving

The subject of drawing and carving of teeth is being introduced at this point because it has been found through experience that a laboratory course in tooth morphology (dissection, drawing, and carving) should be carried on simultaneously with lectures and reference work on the subject of dental anatomy. Illustrations and instruction in tooth form drawing and carving, however, are not included here.

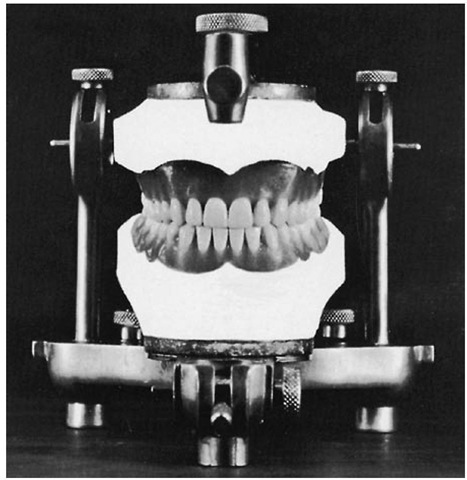

The basis for the specifications to be used for carving individual teeth is a table of average measurements for permanent teeth given by Dr. G. V. Black.6 However, teeth carved or drawn to these average dimensions cannot be set into place for an ideal occlusion. Therefore, for purposes of producing a complete set of articulated teeth (Figures 1-16, 1-17, and 1-18) carved from Ivorine, minor changes have been made in Dr. Black’s table. Also, carving teeth to natural size, calibrated to tenths of a millimeter, is not practical. The adjusted measurements are shown in Table 1-1. The only fractions listed in the model table are 0.5 mm and 0.3 mm in a few instances. Fractions are avoided whenever possible to facilitate familiarity with the table and to avoid confusion.

A table of measurements must be arbitrarily agreed upon so that a reasonable comparison can be made when appraising the dimensions of any one aspect of one tooth in the mouth with that of another. It has been found that the projected table functions well in that way. For instance, if the mesiodistal measurement of the maxillary central incisor is 8.5 mm, the canine will be approximately 1 mm narrower in that measurement; if by chance the central incisor is wider or narrower than 8.5 mm, the canine measurement will correspond proportionately.

Figure 1-16 Carvings in Ivorine of individual teeth made according to the table of measurements (see Table 1-1). Because skulls and extracted teeth show so many variations and anomalies, an arbitrary norm for individual teeth had to be established for comparative study. Hence, the 32 teeth were carved at natural size and in normal alignment and occlusion, and from the model a table of measurements was drafted.

Photographs of the five aspects of each tooth (mesial, distal, labial or buccal, lingual, and incisal or occlusal) superimposed on squared millimeter cross-section paper reduces the tooth outlines of each aspect to an accurate graph, so that it is possible to compare and record the contours (Figures 1-19 and 1-20).

Close observation of the outlines of the squared backgrounds shows the relationship of crown to root, extent of curvatures at various points, inclination of roots, relative widths of occlusal surfaces, height of marginal ridges, contact areas, and so on.

It should be possible to draw reasonably well an outline of any aspect of any tooth in the mouth. It should be in good proportion without reference to another drawing or three-dimensional model.

For the development of skills in observation and in the restoration of lost tooth form, some specific criteria are suggested:

1. Become so familiar with the table of measurements that it is possible to make instant comparisons mentally of the proportion of one tooth with regard to another from any aspect.

2. Learn to draw accurate outlines of any aspect of any tooth.

Figure 1-17 Another view of the models shown in Figure 1-16.

3. Learn to carve with precision any design one can illustrate with line drawings.