Military official of the Twelfth Dynasty

He served senwosret iii (r. 1878-1841 b.c.e.) as a commander of troops. Khusebek accompanied Senwosret III on punitive campaigns in Syria and in nubia (modern Sudan). His mortuary stela announces his career and honors, detailing the military efforts of his time. The stela was discovered at abydos.

Khuy (fl. 23rd century b.c.e.)

Father-in-law of Pepi I (2289-2255 b.c.e.)

Khuy was a nomarch and the father of ankhnesmery-re (1) and (2), who became pepi i’s consorts and the mothers of the heirs. His son, Djau, served as counselor and adviser for pepi i and pepi ii.

King Lists

These are the historical monuments or documents that provide accounts of the rulers of Egypt in chronological order, some providing traditions of the cartouches of the pharaohs. These king lists include

Abydos

Tablet a list discovered in the corridors of the Hall of the Ancestors in the mortuary temple of seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.) in abydos. This list contains the names of the rulers from aha (Menes) c. 2920 B.c.E.to Seti I, a total of 76 rulers. There are reportedly intentional omissions in the Abydos Tablet, including the Second Intermediate Period rulers, akhenaten, and other ‘amarna rulers. ramesses ii copied the list for his own temple. The Abydos Tablet is in the British Museum in London.

Karnak

Tablet inscribed on the festival hall of tuthmosis iii at Karnak and using the nesu or royal names of pharaohs from aha (Menes) (c. 2920 b.c.e.) to Tuthmosis III (1479-1425 b.c.e.). Based on earlier traditions, the list is not as accurate as seti i’s at abydos. Of particular interest, however, are the details of the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1550 b.c.e.) rulers. The Karnak Tablet is in the Louvre in paris.

Manetho’s King List the assembled record of Egyptian rulers compiled by manetho, a historian of sebenny-tos who wrote during the reign of ptolemy i soter (304-284 b.c.e.) and ptolemy ii philadelphus (285-246 b.c.e.). This King List can be found in the Chronography of George Monk and the Syncellus of Tarassus, patriarch of Constantinople, who lived in the eighth century c.e. The oldest version is in the Chronicle of Julius Africanus, a Libyan of the third century c.e. This work, in turn, became part of the Chronicle of Eusebius, the bishop of Caesarea, 264-340 c.e.

Palermo Stone a great stone slab, originally seven feet long and two feet high, now in five fragments. The largest fragment is in the palermo Museum in italy. The stone is made of black diorite and is inscribed with annals of the various reigns. It dates to the Fifth Dynasty (2465-2323 b.c.e.). A secondary piece is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and another is in the Petrie Collection at university college in London. smaller versions of the Palermo Stone have been discovered in private tombs, mines, and quarries.

Saqqara Tablet a monument found in the tomb of the royal scribe Thunery (Tenroy), and probably dating to the reign of ramesses ii (1290-1224 b.c.e.). The table uses the nesu names (one of the royal names) of 47 rulers, starting in the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.). it is now in the Egyptian Museum in cairo.

Turin Canon a document sometimes called the Turin Royal Papyrus, compiled in the reign of ramesses ii (1290-1224 b.c.e.). Done in the hieratic script, the Turin list begins with the dynasties of the gods and continues to Ramesses ii. it is considered the most reliable of the king lists, but some of the names recorded in it are no longer decipherable. originally in the possession of the King of Sardinia, the Turin Canon was sent to Turin, Italy, and was damaged in the process.

kites (1)

These were the names applied by the Egyptians to the goddesses isis and nephthys as part of the osirian cultic rituals. The goddesses lamented the death of osiris, and their song of mourning was a popular aspect of the annual festivals of the god.

kites (2)

They were Egyptian women who were hired or pressed into service during funerals to accompany and greet the coffins of the deceased when they were carried to the necropolises. Professional mourners, the kites wailed and evidenced their grief at each funeral. They are pictured in some renditions of the topic of the dead.

Kiya (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Eighteenth Dynasty, possibly a Mitanni princess She was a secondary consort of akhenaten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.). There is some indication that her origins were Mitanni and that she was named tadukhipa, being the daughter of King tushratta. It is also possible that she was a noble woman from akhmin. Kiya was held in high regard in Akhenaten’s ninth regnal year, but she was out of favor by regnal year 11. she is recorded as having borne two sons and a daughter by Akhenaten, and she was portrayed on monuments in ‘amarna.

After regnal year 11, however, she is no longer visible, and her name was removed from some reliefs. Kiya’s coffin, gilded and inlaid in the rishi pattern, was found in Queen tiye’s (1) tomb, apparently having served as a resting place for the remains of smenkhare (r. 1335-1333 b.c.e.). Canopic lids in Tiye’s tomb had portraits of Kiya. Her mummy has not been identified.

Kleomenes (fl. fourth century b.c.e.)

Greek commissioned to build the city of Alexandria by Alexander III the Great (332-323 b.c.e.)

A companion of Alexander iii the great, Kleomenes was charged with building the new capital of Alexandria in the Delta. Kleomenes worked with deinokrates, the architect, and others, including Krateros of Olynthas, in starting the massive projects. Alexandria’s building continued until the reign of ptolemy ii philadelphus (285-246 b.c.e.).

knots considered magical elements by the Egyptians and used in specific ways for cultic ceremonies. amulets used knots as protective shields, and knotted emblems were worn daily. Elaborate golden knots were used on mummies in some periods. The exact cultic value of these designs and their placements varied according to regions and temple traditions.

kohl

The Arabic term for the ancient Egyptian cosmetic used to adorn eyes. Dried remains of the kohl compound have been discovered in tombs, accompanied by palettes, tubs, and applicators. Kohl was a popular cosmetic for all classes.

Kom Aushim

A site in the faiyum region of the Nile, dating to the Middle Kingdom. The pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1783 b.c.e.) used the area for royal retreats. However, no monuments from that dynasty are recognizable now. Kom Aushim was probably letopo-lis, a cult center of horus, called Hem by the Egyptians.

Kom Dara

This was a site in the necropolis near assiut, with a vast tomb structure dating to the First Intermediate Period (2134-2040 b.c.e.). Massive, with vast outer walls, the tomb contains a sloping corridor leading to a subterranean chamber. No identification has been made as to the owner of the Kom Dara monument.

Kom el-Haten

A site on the western shore of thebes, famed for the mortuary temple of amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) and the seated figures of that pharaoh, called the colossi of memnon, the area was part of the vast necropolis serving Thebes, Egypt’s New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) capital. The temple no longer stands, having been used as a quarry for later dynasties and looted by the locals.

Kom Medinet Ghurob (Mi-Wer)

This was a site on the southeastern end of the faiyum, also called mi-wer in ancient records. tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty established the site as a royal harem retreat and retirement villa. Two temples were erected on the site, now in ruins, as well as the royal harem residence. Kom Medinet Ghurob was used until the reign of ramesses v (1156-1151 b.c.e.). A central building with an enclosing wall, covering the area of three modern city blocks, composed this complex. Objects from the reign of Amenhotep III (1391-1353 b.c.e.) were found on the site. A head of Queen tiye (1), fashioned out of wood, glass, and gesso, was discovered there. This head provides a remarkably individualistic portrait.

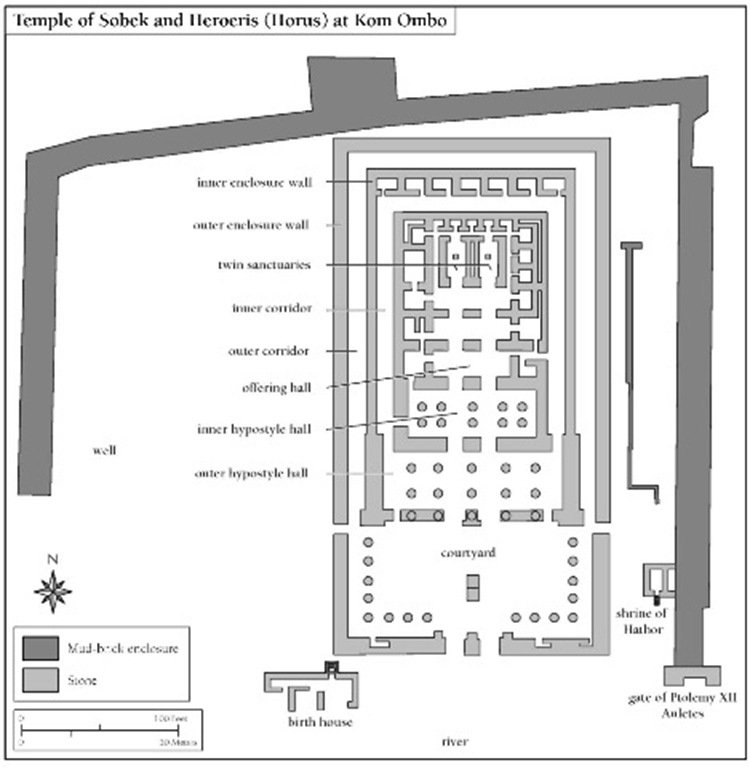

Kom Ombo

A site south of edfu on the Nile that served as the cultic center for the deities horus the Elder and sobek, Kom Ombo was also a major center of Egyptian trade with the Red Sea and Nubian (modern Sudanese) cultures. Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 b.c.e.) structures made Kom Ombo important, but there were also settlements from the paleolithic period in the area.

The temple of Haroeris (horus) and sobek was a double structure, with identical sections, the northern one for Haroeris and the southern one for sobek. There was also a shrine to hathor on the site. The complex was dedicated as well to khons (1). Tasenetnofret, an obscure goddess called “the Good Sister,” and Pnebtawy, called “the Lord of the Two Lands,” were honored as well at Kom Ombo.

A double entrance is in the southwest, leading to a courtyard. Two hypostyle halls, offering halls, twin sanctuaries, magazines, vestibules, wells, and birth houses, called MAMMISI, compose the elements of the temple. The main temple is Ptolemaic in its present form, with a gate fashioned by ptolemy xii Auletes (r. 80-58, 55-51 B.C.E.). Niches and crypts were also included, and mummies of crocodiles were found, wearing golden earrings, manicures, and gilded nails. A nilometer was installed at Kom Ombo, and calendars and portraits of the Ptolemys adorned the walls.

Konosso

A high-water island, dating to the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 B.C.E.), it was a staging point for trade and expeditions to nubia (modern Sudan). An inscription of tuthmosis iv (r. 1401-1391 b.c.e.) at Konosso gives an account of the site’s purpose.

Koptos (Gebtu, Kabet, Qift)

This was a site south of qena, called Gebtu or Kabet by the Egyptians and Koptos by the Greeks, serving as the capital of the fifth nome of upper Egypt and as a center for trade expeditions to the Red Sea. Koptos was also the cult center of the god min (1). Min shared a temple with the goddess isis. Three pylons and a processional way that led to a gate erected by tuthmosis III (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) were part of the temple design. horus was also honored in this temple, spanning Egypt’s history. ptolemy ii philadelphus (r. 285-246 b.c.e.) added to the temple, as did ptolemy iv philopator (r. 221-205 b.c.e.). An original temple on the site had been erected and adorned by amenemhet i (r. 1991-1962 b.c.e.) and senwosret I (r. 1971-1926 b.c.e.). A chapel of the god osiris dates to the reign of Amasis (570-526 b.c.e.). A middle temple has additions made by osorkon ii (r. 883-855 b.c.e.). A temple that was discovered in the southern area of Koptos was refurbished by nectanebo ii (r. 360-343 b.c.e.). cleopatra vii (r. 51-30 b.c.e.) and ptolemy XV Caesarion (r. 44-30 b.c.e.) also constructed a small chapel on the site. This chapel was used as an oracle. Koptos also had gold mines and quarries, being located near the wadi hammamat.

Koptos Decree

This was a document from the Sixth Dynasty, in the reign of pepi i (2289-2255 b.c.e.). Found in the temple of min (1) at Koptos, the Decree grants immunity from taxes for all residents of the mortuary chapel for Pepi I’s royal mother, Queen iput. This chapel was connected to Min’s temple. The personnel of Queen iput’s (2) cult were also freed from the responsibility of paying for the travel of officials and the visit of any royal retinues. such tax-exemption decrees were frequent in many periods, particularly for complexes concerned with mortuary cults.

Korosko

This is a site in nubia, modern Sudan, located between the first and second cataracts of the Nile. An inscription there from the 29th year of amenemhet i (r. 1991-1962 b.c.e.) of the Twelfth Dynasty describes how the people of wawat, the name for that area of the Nile, were defeated by the pharaoh’s army.

Kula, el-

A site on the western shore of the Nile, northwest of hierakonpolis and elkab. The remains of an Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.) step pyramid were discovered there, without the usual complex structures. No identification of the pyramid has been possible to date.

Kurgus

A site at the fifth cataract in nubia (modern Sudan), conquered by tuthmosis i (r. 1504-1492 b.c.e.) and maintained by tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.), Kurgus has a carved inscription designating it as Egypt’s southern boundary. The city was involved in an overland trade route through wadi alaki.

Kurigalzu (1) (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

King of Kassite Babylon during the Amarna Period of Egypt He was noted in the ‘amarna correspondence as receiving gold as a gift from amenhotep iii (1391-1353 b.c.e.). Kurigalzu aided Egyptian ambitions on the Mediterranean coast.

Kurigalzu (2) (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

King of Kassite Babylon in the reign of Akhenaten

He attacked the Elamites in the neighboring region and captured their capital of susa, destroying Egypt’s imperial structures in the area. Kurigalzu was reported in the ‘amarna letters.

Kuser

A port on the Red sea, also called sewew, Kuser was located to the east of koptos and was used extensively by the Egyptians. A shipbuilding industry prospered there, as Kuser was a staging point for maritime expeditions to punt in many eras of the nation’s history, particularly in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.).

kyphi

This was the Greek form of the Egyptian kapet, a popular incense or perfume of ancient Egypt, composed of many ingredients. The formulas varied considerably and were mentioned in medical texts. Kyphi was also used as a freshener for the air and clothes (even though the formulas included at times the excrement of animals). As a mouthwash it could be mixed with wine. Kyphi was sometimes used as incense in the ptolemaic period (304-30 B.c.E.), and formulas were discovered on the walls of the edfu and philae temples.

Lab’ayu (fl. 14th century b.c.e.)

Prince of Canaan during the Amarna Period

The prince’s correspondence with amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) demonstrates the role of vassal states in the vast Egyptian empire of that historical period. Lab’ayu, whose capital was at Sechem, raided his neighbors in the hill country of northern Palestine, and Prince biridiya of ar-megiddo wrote to Amenhotep III to complain about the problem. Lab’ayu was warned by Egyptian officials and sent word to Amenhotep iii that he was innocent of all charges and loyal to the pharaoh. The Canaanite prince died in the reign of akhenaten (1353-1335 b.c.e.).

Labyrinth

This is the Greek name given to the pyramid complex of amenemhet iii (1844-1797 b.c.e.) at hawara, near the faiyum. The exact purpose of the complex has not been determined, but the name was bestowed upon the site because of the architectural complexity of the design. Shafts, corridors, and stone plugs were incorporated into the pyramid, and a central burial chamber was fashioned out of a single block of granite, weighing an estimated 110 tons. There are also shrines for nome deities in the structure and 12 separate courts, facing one another, and demonstrating the architectural wonders of the site. An obvious burial complex, the Labyrinth has also been identified as an administrative or cultic center of the time.

ladder

A mystical symbol associated with the cult of the god osiris, called a magat. Used as an amulet, the ladder honored the goddess nut, the mother of osiris.

Models of the ladder were placed in tombs to invoke the aid of the deities. The ladder had been designed by the gods to stretch mystically when osiris ascended into their domain. As an amulet, the ladder was believed to carry the deceased to the realms of paradise beyond the grave.

Ladice (fl. sixth century b.c.e.)

Royal woman of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty

The consort of amasis (r. 570-526 b.c.e.), Ladice was a cyrenaica noble woman, possibly a member of the royal family of that state. Her marriage was undoubtedly part of a treaty between Egypt and cyrene in North Africa.

Lagus (fl. fourth and third centuries b.c.e.)

Greek military companion of Alexander the Great and the father of Ptolemy I Soter

Lagus served Alexander [iii] the great in campaigns and aided Ptolemy’s career. He was married to arsinoe (5), the mother of ptolemy i soter. The Ptolemaic royal line (304-30 b.c.e.) was called the Lagide Dynasty in honor of Lagus’s memory.

Lahun, el- A site in the faiyum region of Egypt, located south of crocodilopolis (Medinet el-Faiyum), the necropolis of kahun is located there as well. The river bahr yusef (not of biblical origin, but honoring a local hero of Islam) enters the Faiyum in this area. El-Lahun was a regulating station for the Faiyum and the Bahr Yusef. in certain times of the year, corresponding to the modern month of January, the sluices were closed to drain the area and to clear the waterways and bridges.

Dominating the site is a pyramidal complex erected by senwosret ii (r. 1897-1878 b.c.e.). Made out of mud brick, the pyramid was erected on a rocky outcropping and had a stone casing. The mortuary temple of the complex was covered by red granite, and the surfaces were decorated with inscriptions. The burial chamber was lined with red granite slabs and contained a red granite sarcophagus. A subsidiary pyramid was erected nearby, enclosed within the main wall. papyri from the period were discovered there, as well as medical instruments.

Lake of Fire

This was a mysterious Underworld site designated in the mortuary relief called the topic of Gates. This text appears for the first time in the tomb of horemhab (r. 1319-1307 b.c.e.). The Lake of Fire was located in “the Sacred Cavern of Sokar” and was the ultimate destination of damned souls. No one returned from the Lake of Fire, which burned in a sunless region.

Lake of Flowers

The poetic name for one of the eternal realms of paradise awaiting the Egyptians beyond the grave, the site contained all the elements deemed inviting, such as fresh water, cool winds, and flowers. The Egyptians, surrounded by deserts in all eras, were quite precise about the necessary aspects of amenti, the joyful existence prepared for the dead in the west. other designations provided similar attributes and were called the lily lake and the Fields of Food.

lakes

These were the water sources of Egypt beyond the boundaries of the Nile, part of the geographical composition of the Nile Valley. The scant rainfall, especially in upper Egypt, made the land arid and devoid of any lake. The Delta and the faiyum areas of Lower Egypt, however, were graced with seven lakes in ancient times. They were qurun (Birkat el-Qurun), natron, Manzilah, edku, Abukir, mareotis, and Barullus. siwa Oasis in the libyan or Western desert was graced by Lake Zeytun.

Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys

This is an ancient hieratic document from around 500 b.c.e. that was part of the Osirian cult. isis and nephthys wept over osiris after he was slain by the god set. The two goddesses also proclaimed osiris’s resurrection from the dead and his ascension into heaven. During the Late Period (712-332 b.c.e.), Osirian dramas were revived, and elaborate ceremonies were staged with the Lamentations as part of the rituals. Both the goddesses isis and Nephthys were portrayed by priestesses during the ceremonies in which the hymn was sung, or the Songs, as they were also called, were read by a priest. These ceremonies were celebrated in the fourth month of the year, approximately December 21 on the modern calendar. The Lamentations were also called the Festival Songs of the Two Weepers. in time, the Lamentations were added to versions of the topic of the dead.

Land of the Bow

This was a region of nubia (modern Sudan) controlled by Egypt from the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 b.c.e.) until the end of the New Kingdom (1070 b.c.e.). The area below the first cataract, also called wawat, attracted the Egyptians because of the local natural resources and the advantageous trade routes. Associated with the concept of the nine bows, the Land of the Bow was displayed in carvings on royal standards. other lands of the east assumed that title in certain reigns. in some periods the Nine Bows were depicted on the inside of the pharaoh’s shoes, so that he could tread on them in his daily rounds.

language

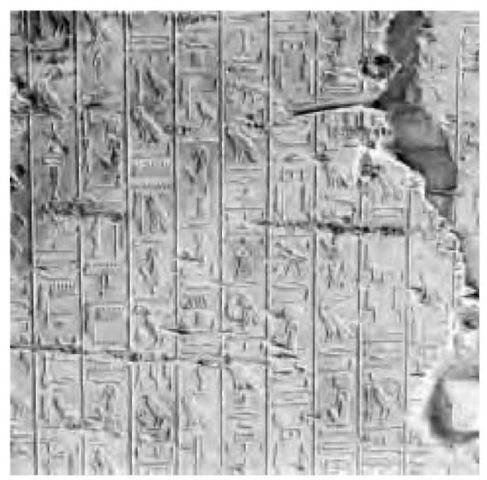

The oral and written systems of communication of ancient Egypt were once thought to have been a late development on the Nile but are now recognized as an evolving cultural process that is contemporaneous with, if not earlier than, the sumerian advances. The clay tablets discovered recently in the tomb of an obscure ruler, scorpion, at Gebel Tjauti, date to between 3700 b.c.e. and 3200 b.c.e., thus marking Egypt’s use of a written language at an earlier historical date not recognized previously. The hieroglyphs inscribed on the tablets were used in varied forms throughout Egypt’s history, the last known display being inscribed at philae, dated 394 b.c.e.

The introduction of hieroglyphs was one of the most important developments in Egypt, as a tradition of literacy and recorded knowledge was thus begun. Not everyone in Egypt was literate, of course, but standards of education were set and maintained as a result, norms observed through the centuries by the vast armies of official scribes. in the beginning, the use of hieroglyphs was confined to a class of priests, and over the years the language in the oral form grew sophisticated and evolved, but the hieroglyphs remained comparatively traditional, protected against inroads by the priestly castes that trained the multitude of scribes. The hieroglyphs were normally used for religious texts, hence the Greek name hieroglyph (“sacred carvings”). The linguistic stages of development are as follows:

Old Egyptian is the term used to designate the language of the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 b.c.e.) and the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.). Extant texts from this period are mostly official or religious, including the pyramid texts, royal decrees, tomb inscriptions, and a few biographical documents.

Middle Egyptian, the linguistic form of the First Intermediate Period (2134-2040 b.c.e.), was used through the New Kingdom and later. This is classic hieroglyphic writing, used on monuments and on the famed rosetta stone.

The Late Egyptian writings included the classic hieroglyphs and the hieratic form. Definite and indefinite articles were included, and phonetic changes entered the language. in the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664-525 B.c.E.), the demotic form became the accepted language. During the persian, Greek, and Roman periods of occupation on the Nile, the demotic form was used for legal documents, literary, and religious texts. The demotic is also included in the Rosetta stone.

Hieroglyphic Egyptian is basically a pictorial form, used by the early Egyptians to record an object or an event. The hieroglyph could be read as a picture, as a symbol of an image portrayed, or as a symbol for the sounds related to the image. in time the hieroglyphs were incorporated into art forms as well, inserted to specify particulars about the scene or event depicted.

Hieroglyphs were cut originally on cylindrical seals. These incised, roller-shaped stones (later replaced by handheld scarab seals) were rolled onto fresh clay jar stoppers. They were used to indicate ownership of an object (particularly royal ownership) and designated the official responsible for its care. such cylinders and seals were found in the predynastic period (before 3000 B.c.E.) and First Dynasty (2920-2770 B.c.E.) tombs. Hieroglyphs accompanying the artistic renditions of the Early Dynastic period (2920-2575 B.c.E.) began to conform to certain regulations. At the start of the old Kingdom, a canon of hieroglyphs was firmly in place. From this period onward the hieroglyphic writing appeared on stone monuments and bas-reliefs or high reliefs. The hieroglyphs were also painted on wood or metal. They were incorporated into temple decorations and were also used in coffins, stelae, statues, tomb walls, and other monumental objects.

Hieroglyphs, the writing of ancient Egyptians, now known to be in use long before the unification of the Two Kingdoms, c. 3,000 b.c.e.

The obvious limitations of hieroglyphs for practical, day-to-day record keeping led to another, cursive form, called the hieratic. in this form the hieroglyphs were simplified and rounded, in the same way that such writing would result from the use of a reed-pen rather than a chisel on a stone surface. in the old Kingdom (25752134 B.c.E.) the hieratic was barely distinguishable from the hieroglyphic, but in the Middle (2040-1640 B.c.E.) and New Kingdoms (1550-1070 B.c.E.) the form was developing unique qualities of its own. This form was used until the Roman era, c. 30 B.c.E., although during the ptolemaic period (304-30 B.c.E.) Greek was the official language of the Alexandrian court. cleopatra vii (51-30 B.c.E.) was the only member of her royal line that spoke the Egyptian language.

The Egyptian language in the written form (as it reflected the oral traditions) is unique in that it concerns itself with realism. There is something basically concrete about the images depicted, without speculative or philosophical nuances. Egyptians had a keen awareness of the physical world and translated their observances in images that carried distinct symbolism. Gestures or positions reflected a particular attribute or activity. The hieroglyphs were concise, strictly regulated as to word order, and formal.

in the hieroglyphic writing only two classes of signs need to be distinguished: sense signs, or ideograms, and sound signs, or phonograms. The ideograms represent either the actual object depicted or some closely connected idea. phonograms acquired sound values and were used for spelling. The vowels were not written in hieroglyphs, a factor which reflects the use of different vocalizations and context for words in the oral Egyptian language. The consonants remained consistent because the pronunciation of the word depended upon the context in which it appeared.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions consisted of rows of miniature pictures, arranged in vertical columns or horizontal lines. They normally read from right to left, although in some instances they were read in reverse. The signs that represented persons or animals normally faced the beginning of the inscription, a key as to the direction in which it should be read.

The alphabet is precise and includes specific characters for different sounds or objects. For each of the consonantal sounds there were one or more characters, and many single signs contained from two to four sounds. These signs, with or without phonetic value, were also used as determinatives. These were added at the ends of words to give them particular action or value. The decipherment of hieroglyphic writing was made possible with the discovery of the Rosetta stone. since that time, the study of Egypt’s language has continued and evolved, enabling scholars to reassess previously known materials and to elaborate on the historical evidence concerning the people of the Nile.

Lansing Papyrus

This is a document now in the British Museum in London that appears to be related to the school and scribal systems of Egypt. The text of the papyrus praises scribes and extols the advantages of education and learning.

lapis lazuli

This is a semiprecious stone, a form of limestone, blue mineral lazurite, preferred by Egyptians over gold and silver. The stone, which could be opaque, dark, or greenish blue, was sometimes flecked with gold and was used in all eras, especially as amulets, small sculptures, and scarabs. The Egyptian name for lapis lazuli was khesbedj, representing vitality and youthful-ness. Lapis lazuli originated in northeastern Afghanistan and was imported into Egypt. The goddess hathor was sometimes called the “Mistress of Lapis Lazuli.”

Lateran Obelisk

This is a monument belonging to tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) that was carved but not erected at karnak until the reign of tuthmosis iv (1401-1391 b.c.e.). Tuthmosis IV had the unattended obelisk raised and put in a place in the Karnak sacred precincts. The monument carries an inscription that attests to Tuthmosis iv’s filial piety in performing that deed. The obelisk is now on display in the vatican in Rome.

Layer Pyramid

This is the modern name given to the monument erected at zawiet el-aryan at giza by kha’ba (r. 2603-2599 B.c.E.).

Lay of the Harper

This is an unusual text discovered on tomb walls and other monuments of Egypt, reflecting upon death. containing pessimistic views contrary to the accepted religious tenets concerning existence beyond the grave, the Lay of the Harper is solemn and foreboding. One version, found at thebes and reportedly copied from the tomb of inyotef v (r. c. 1640-1635 b.c.e.) of the seventeenth Dynasty, is also called the Harper’s song. This text doubts the existence of an eternal paradise and encourages a hedonistic approach to earthly life that is contrary to the normal Egyptian concept of MA’AT.

legal system

The extensive and comprehensive judicial system developed in ancient Egypt as part of the national and provincial forms of government. The people of the NILE remained close-knit in their NOME communities, even at the height of the empire, and they preferred to have their court cases and grievances settled under local jurisdiction. Each nome or province had a capital city, dating to predynastic times. Lesser cities and towns within the nome functioned as part of a whole. in each town or village, however, there was a seru, a group of elders whose purpose it was to provide legal opinions and decisions on local events. The court, called the djatjat in the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.) and the KENBET thereafter, made legal and binding decisions and meted out the appropriate penalties. The kenbet was a factor on both the nome and high-court levels. This series of local and national courts followed a well-understood tradition of hearings and judgments.

only during the periods of unrest or chaos, as in the two Intermediate Periods (First, 2134-2040 b.c.e.; Second, 1640-1550 B.c.E.), did such a custom prove disastrous. The popularity of the “eloquent peasant,” the tale of khunianupu, was due to the nation’s genuine desire to have courts provide justice. crimes involving capital punishment or those of treason, however, were not always within the jurisdiction of the local courts, and even the Great kenbet, the supreme body of judgment, could not always render the ultimate decision on such matters.

The Great kenbets in the capitals were under the supervision of the viziers of Egypt; in several periods there were two such offices, a vizier for Upper Egypt and another for Lower Egypt. This custom commemorated the unification of the nation in 3000 B.c.E. petitions seeking judicial aid or relief could be made to the lower courts, and appeals of all lower court rulings could be made to the Great kenbet by all citizens. Egyptians waited in line each day to give the judges their testimony or their petitions. The decisions concerning such matters were based on traditional legal practices, although there must have been written codes available for study horemhab (r. 1319-1307 b.c.e.), at the close of the Eighteenth Dynasty, set down a series of edicts concerning the law. He appears to be referring to past customs or documents in his decrees concerning compliances and punishments.

No distinction was allowed in the hearing of cases. commoners and women were afforded normally the same opportunities as aristocrats in the courts. The poor were also to be safeguarded in their rights. The “Eloquent peasant” was popular because he dared to admonish the judges again and again to give heed to the demands of the poor and not to be swayed by the mighty, the well connected, or the popular. The admonitions to the viziers of Egypt, as recorded in the Eighteenth Dynasty (15501307 b.c.e.) tomb of rekhmire, echo the same sort of vigilance required by all Egyptian officials.

some of the higher ranking judges of ancient Egypt were called “Attached to Nekhen,” a title of honor that denoted the fact that their positions and roles were in the finest traditions of hierakonpolis, the original home of the first unifier of Egypt around 3000 b.c.e., narmer. The title alluded to these judges’ long and faithful tradition of service and their role in preserving customs and legal traditions of the past. Others were called the “magnates of the southern ten,” and these officers of the government were esteemed for their services and for their rank in powerful Upper Egyptian nomes or capitals. When Egypt acquired an empire in the New Kingdom era (1550-1070 b.c.e.), various governors were also assigned to foreign territories under Egyptian control, and these held judicial posts as part of their capacity. The viceroy of nubia, for example, made court decisions and enforced the law in his jurisdiction.

The judicial system of ancient Egypt, collapsing during the various periods of unrest or foreign dominance that inflicted damage on the normal governmental structures, appears to have served the Egyptians well over the centuries. under strong dynasties, the courts and the various officials were expected to set standards of moral behavior and to strictly interpret the law.

During the Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) the traditional court systems of Egypt applied only to native Egyptians. The Greeks in control of the Nile Valley were under the systems imported from their homelands. This double standard was accepted by the common people of Egypt as part of the foreign occupation. They turned toward their nomes and their traditions.