In 332 b.c.e., Alexander iii the great, having defeated the Persian forces of Darius III Codoman in a series of military campaigns, took control of Egypt, founding the city of Alexandria. At his death the nation became the property of ptolemy i soter (r. 304-284 b.c.e.), one of his generals. For the next 250 years the Greeks successfully ruled Egypt, imbuing the land with the Hellenic traditions in the capital but not affecting rural Nile areas. it was a time of economic and artistic prosperity, but by the second century b.c.e., there was a marked decline. Family feuds and external forces took their toll, even though the Ptolemaic line remained in power. This royal house died with cleopatra vii (r. 51-30 b.c.e.) and her short-lived corulers. Octavian (the future emperor Augustus) took control and began the period of Roman occupation, c. 30 b.c.e. Egypt became a prized possession of Rome, protected by the caesars.

Egypt and the East

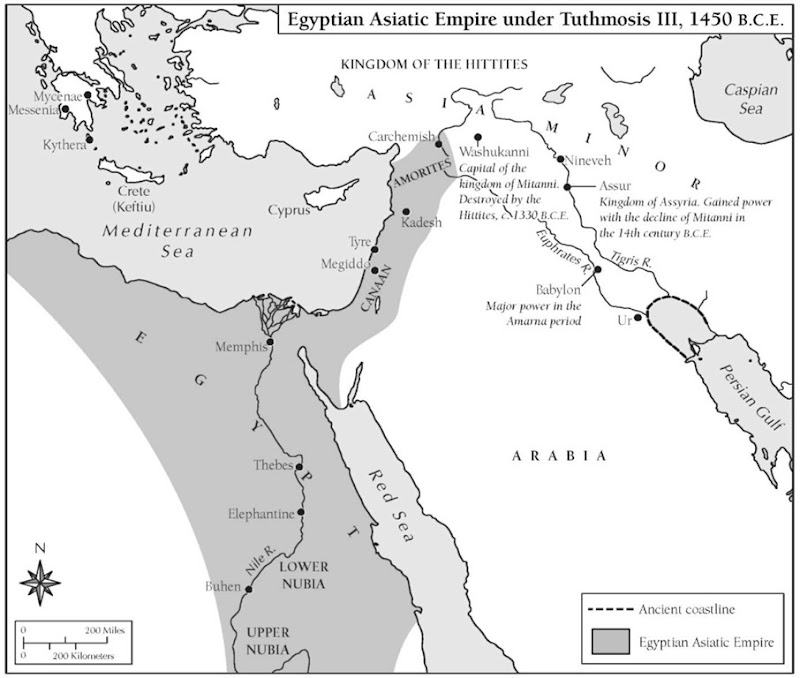

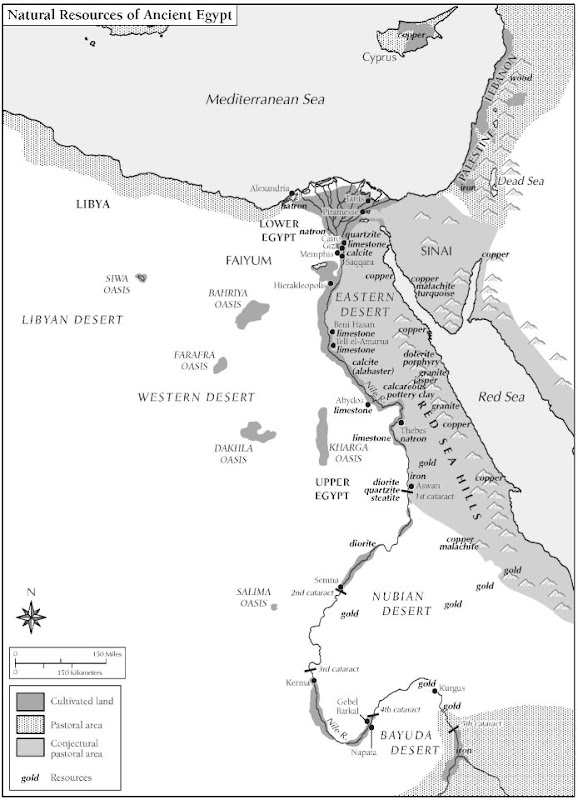

The relationship between the Nile Valley and Mediterranean states was complex and subject to many historical factors, including dynastic vitality and foreign leadership. From the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 b.c.e.), Egypt guarded its borders, especially those that faced eastward, as Egyptians had ventured into the sinai and opened copper and turquoise mines in that area, repulsing the Asiatics and staking their own claims. The Egyptians maintained camps and fortresses in the area to protect this valuable fount of natural resources. in the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.), the Egyptians led punitive raids against their rebellious eastern vassals and defended their borders furiously. In the Sixth Dynasty (2323-2150 b.c.e.), the leadership of General weni ushered in a new period of Egyptian military expansion, and the people of southern palestine began to look toward the Nile uneasily. weni and his Nubian mercenaries and conscripts raided the lands and the natural resources of much of southern Palestine.

During the First Intermediate Period (2134-2040 b.c.e.), Egyptians held onto limited powers until Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) pharaohs secured Egypt’s borders again and established a firm rule. The Mon-tuhoteps, Amenemhets, and Senwosrets were warrior pharaohs who conquered entire city-states, establishing vassals and trade partners while controlling the people of Nubia. This relationship with other states lasted until the Second Intermediate Period (1640-1550 b.c.e.), at which time vast hordes of Asiatics entered the Nile region with ease. In this era it appears as if no border existed on the eastern side of the nation, and many peoples in southern Palestine viewed themselves as Egyptians and lived under the rule of the hyksos kings of the eastern Delta. The Eighteenth Dynasty changed that condition abruptly. ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.) chased the Asiatics from Egypt and sealed its borders, reestablishing the series of fortresses called the wall of the prince erected during the Middle Kingdom period.

amenhotep i (r. 1525-1504 b.c.e.) maintained this firm rule, but it was his successor, tuthmosis i (r. 1504-1492 b.c.e.), who defeated the mitannis, once Egypt’s principal Asiatic enemies, and marched to the Euphrates River with a large army. The Mitannis remained firm allies of Egypt from that time onward, and many treaties and pacts maintained the partitioning of vast territories between them. Mitanni princesses also entered Egypt as wives of the pharaohs. The Mitanni people flowered as an empire, having started their invasion of neighboring lands during Tuthmosis I’s era. In time they controlled city-states and kingdoms from the zagros Mountains to Lake Van and even to Assur, proving to be loyal allies of Egypt. They suffered during the ‘amarna Period (1353-1335 b.c.e.), when akhenaten failed to meet the challenge of the emerging hittites and their cohorts and the roving bands of barbarians who were migrating throughout the Mediterranean region. The Ramessids, coming to power later, could not protect the Mitannis either. By that time the Mitanni kingdom had already been subjugated by the warriors of the hittites. When tuthmosis iii came to the throne in 1479 b.c.e., the Mitannis were still in power, and the Hittites were consumed by their own internal problems and by wars with their immediate neighbors.

He began campaigns in southern palestine and in the city-states on the Mediterranean coast, eventually reaching the Euphrates. palestine and the sinai had been under Egypt’s control since Tuthmosis I. A confederation of states threatened by Egypt, or in the process of seeking total independence, banded under the leadership of the king of kadesh. Tuthmosis III met them at ar-megiddo, near Mount carmel, and laid siege. He then attacked Phoenicia (modern Lebanon) and fortified the coastal cities there, placing them all under Egyptian control. Egypt, as a result, received gifts and tribute from Babylon, Assyria, cyprus, Crete, and all of the small city-states of the Mediterranean region. Even the Hittites were anxious to send offerings and diplomats to the Egyptian court at thebes.

Tuthmosis Ill’s son, amenhotep ii (r. 1427-1401 b.c.e.) conducted ruthless campaigns in Syria and governed the provinces with a firm hand. His heir, tuthmosis iv (r. 1401-1391 b.c.e.), did not have to exert himself, because the tributary nations were not anxious to provoke another Egyptian invasion. amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) came to power in an era of Egyptian supremacy, and he too did not have difficulty maintaining the wealth or status of the nation. His son, Akhenaten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.), however, lost control of many territories, ignoring the pleas of his vassal kings and allies when they were threatened by hostile forces instigated by the Hittites.

The Hittites had arrived at the city of Hattus sometime c. 1400 b.c.e. and renamed it Hattusa. This capital became a sophisticated metropolis in time, with vast fortified walls complete with stone lions and a sphinx gate. The Hittites conquered vast regions of Asia Minor and Syria. They worshiped a storm god and conducted administrative, legislative, and legal affairs ably. They worked silver, gold, and electrum skillfully, maintained three separate languages within their main territories, kept vast records, and protected the individual rights of their own citizens. Their legal code, like the Hammurabic code before it, was harsh but just. The Hittites were warriors, but they were also capable of statecraft and diplomacy.

The son of Hittite king suppiluliumas i was offered the Egyptian throne by tut’ankhamun’s young widow, ankhesenamon, c. 1323 b.c.e. Prince zannanza, however, was slain as he approached Egypt’s border. horemhab (c. 1319-1307 b.c.e.) who became the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, was probably the one who ordered the death of the Hittite prince, but when he came to power he was able to arrange a truce between the two nations. He needed to maintain such a pact in order to restore Egypt’s internal affairs, greatly deteriorated by Akhenaten’s reign.

The first Ramessid kings, all military veterans, were anxious to restore the empire again, and they began to assault Egypt’s former provinces. They watched the Hit-tites begin their own attacks on new territories with growing annoyance. The Hittites had conducted a great syrian campaign, defeating the Mitanni king and attacking that empire’s vassal states as a result. The city-state of Amurru also rose to prominence as the Amurrian king and his heir conducted diplomatic maneuvers and statecraft skillfully as agents of the Hatti. Many loyal Egyptian states fell to them.

The Hittites next assaulted the Hurrian region, taking the city of carchemish. The Hurrians had come into this territory from an unknown land, bringing skills in war, horses, and chariot attacks. in time the Egyptians were the beneficiaries of the Hurrian skills, as many of them entered the Nile Valley to conduct training sessions and programs.

when the Hittites began to invade Egyptian territories, seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.) started a counteroffen-sive. He easily overcame Palestine and Lebanon with his vast and skilled army. He then advanced on Kadesh, a Hittite ally, and consolidated his victories by reaching an agreement with the Hittites over the division of lands and spoils. The Hatti and the Egyptians thus shared most of the Near East with Egypt, maintaining the whole of Palestine and the Syrian coastal regions to the Litani River.

Seti’s son, ramesses ii, faced a reinvigorated Hittite nation, however, one that was not eager to allow Egypt to keep its fabled domain. The battles displayed on Ramesses II’s war memorials and on temple walls, especially the celebrated “Poem” of pentaur, depict the clash between the Hittites and the Egyptians. Ramesses ii and his army were caught in a cleverly devised ambush, but he led his troops out of the trap and managed an effective delaying effort until reinforcements arrived. This, the Battle of kadesh, resulting in heavy losses on both sides, led to the hittite alliance.

From that point on, the Hittites and the Egyptians maintained cordial relations. Both were suffering from the changing arenas of power in the world, and both were experiencing internal problems. it is significant that the successors of Ramesses ii fought against invasions of Egypt as the Hittites faced attacks from enemies of their own. The sea peoples, the sherden pirates, and others were challenging the might and will of these great empires. Men like wenamun, traveling in the last stages of Egyptian decline, faced hostility and contempt in the very regions once firmly within the Egyptian camp.

With the decline and fall of the Ramessid line in 1070 b.c.e., the imperial designs of Egypt faded. The internal rivalries between Thebes and the Delta rulers factionalized the military and political power of the nation. City-states arose, and the nomarchs once again fortified their holdings. tanis, sais, bubastis, and thebes became centers of power, but little effort was made to hold on to the imperial territories, and Egypt settled for trade pacts and cordial relations with surrounding lands.

When the Libyans came to power in 945 b.c.e., however, shoshenq i made successful campaigns in Palestine and amassed vassal states. others in that dynasty were unable to sustain the momentum, however, and Egypt did not affect the Near East but stood vulnerable and partitioned by local clans. The Twenty-third Dynasty (c. 828-712 b.c.e.) and the nation witnessed the disintegration. The Twenty-fourth Dynasty (724-712 b.c.e.), a contemporary line of rulers, joined with their counterparts in facing the Nubian army, led into the various cities of Egypt by piankhi (r. 750-712 b.c.e.).

Egypt was entering the historical era called the Late Period (712-332 b.c.e.), a time of conquest by newly emerging groups in the region. The Assyrians, expanding and taking older imperial territories, arrived in Egypt in the reign of taharqa (690-664 b.c.e.), led by essarhad-don. The Assyrian conquest of Egypt was short, but other rising powers recognized that the Nile Valley was now vulnerable.

The presence of large numbers of Greeks in Egypt added to the relationship of the Nile Valley and the Near East. The Greeks had nakrotis, a city in the Delta, and were firmly entrenched in Egypt by the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664-525 b.c.e.). necho i, psammetichus i, apries, and amasis, all rulers of this line, used other city-states and mercenaries to aid their own causes. They joined confederacies and alliances to keep the Assyrians, Persians, and other military powers at bay

In 525 b.c.e., however, cambyses, the Persian king, marched into Egypt and began a period of occupation that would last until 404 b.c.e. The Persians faced only sporadic resistance during this period. In 404 b.c.e., amyrtaios ruled as the lone member of the Twenty-eighth Dynasty (404-393 b.c.e.), and the Twenty-ninth Dynasty (393-380 b.c.e.) arose as another native Egyptian royal line.

The Persians returned in 343 b.c.e. and ruled in Egypt until darius iii codoman (335-332 b.c.e.) was defeated by Alexander iii the great. Egypt then became part of Alexander’s empire, and ptolemy i soter (r. 304-284 b.c.e.) claimed the land and started the Ptolemaic Period that lasted until the suicide of cleopatra vii.

Throughout the period, the Ptolemaic rulers aligned themselves with many Greek city-states and conducted wars over Hellenic affairs. In 30 b.c.e., Egypt became a holding of the Roman Empire.

Egyptian Empire During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties (1550-1307 b.c.e., 1307-1196 b.c.e.), when the empire was at its zenith, Egypt ruled over an estimated 400,000 square miles of the Middle East, from Khartoum in modern Sudan to carchemish on the Euphrates River and westward to the siwa oasis. By the Twentieth Dynasty (1196-1070 b.c.e.), however, the empire was failing as new and vigorous nations challenged Egypt’s domain.

The rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 b.c.e.), inspired by tuthmosis i (r. 1504-1492 b.c.e.), began the conquest and modernized the military machine of Egypt. kamose (r. 1555-1550 b.c.e.) had continued his father’s war on the hyksos invaders of the Delta with a standing army. In the earlier times, the various nomes of the nation had answered the call of their pharaohs and had gathered small armies to join in military campaigns. Such armies, however, marched behind nomarchs and clan totems and disbanded when the crises were over. Kamose and his successor, ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.), had professional soldiers, a corps of trained officers, and an army composed of regular troops. Instantly, Egypt became a first-class military power with innovative weapons and various units that terrorized neighboring states. From the start, Egypt’s foreign policy was based on a firm control of Palestine, nubia, and Syria.

Pharaoh normally led campaigns in the field, with the Tuthmossids and the Ramessids rising to the occasion and accepting each challenge. If a pharaoh did commit himself to participation in battle, he could rely on trusted generals, veterans of previous campaigns. The fielded army was organized into divisions, each consisting of charioteers and infantry and numbering around 5,000 men or more.

The chaotic conditions of the Middle East at this time aided the single-minded Egyptians in their quest for power. The city of Babylon was in the hands of the Kas-sites, the warrior clans from the eastern highlands. To the north, the mitanni Empire stretched across Iraq and Syria as far as the Euphrates (c. 1500-1370 b.c.e.). The Mitannis were Indo-European invaders who came in the wave of the migrating peoples from the caucasus. The Mitan-nis were enemies of Egypt and Egypt’s allies until accommodations were reached.

The hittites, Indo-Europeans who crossed the Taurus Mountains to found the city of Hatti, were beginning their migratory conquests. In time they would destroy the Mitanni and then become an uneasy neighbor of Egypt. The Eighteenth Dynasty cleared the Nile Valley of the Hyksos and started the era of the greatest imperial achievements. The political and military gains made during the reigns of these pharaohs were never equaled.

The Nubians south of the first cataract had responded to the Hyksos’ offer of alliance and had threatened Upper Egypt. ‘Ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.) subdued Nubia and maintained new defenses along the Nile, refurbishing the fortresses started centuries before. These fortresses were sustained by his successors, and new bastions were added. with the expulsion of the Hyk-sos and the subjugation of nubia, the Egyptians developed a consciousness of the nation’s destiny as the greatest land on earth. The centuries of priests and sages had assured the Egyptians of such a destiny, and now the conquests were establishing such a future as a reality.

Tuthmosis I, the third ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty, carved Egypt’s empire out of the Near East, conquering Mediterranean lands all the way to the Euphrates River. His grandson, tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.), called “the Napoleon of Egypt,” was the actual architect of the empire. He recruited retaliatory military units and established garrisons and administrative policies that kept other potential powers away from Egypt’s holdings and vassal states.

akhenaten (r. 1353-1335 b.c.e.) imperiled the empire, as the ‘Amarna Period correspondence illustrates. horemhab (r. 1319-1307 b.c.e.), however, began the restoration and then named ramesses i (r. 1307-1306 b.c.e.) as his heir. Ramesses I’s son, seti i (r. 1306-1290 b.c.e.), a trained general, and ramesses ii (r. 12901224 b.c.e.), called the Great, as well as merenptah (r. 1224-1214 b.c.e.), all maintained the empire, stretching for a long time from Khartoum in modern Sudan to the Euphrates River. As the sea peoples destroyed the Hittites and other cultures, Egypt remained secure. The last imperial pharaoh was ramesses iii (r. 1194-1163 b.c.e.) of the Twentieth Dynasty. After his death, the Ramessid line collapsed slowly, and Egypt faced internal divisions and the growing menace of merging military powers.

In the Third Intermediate Period, shoshenq i (r. 945-924 b.c.e.) conquered parts of Palestine once again, but these city-states broke free or were overcome by other empires. Egypt was invaded by the syrians, Nubians, persians, and then by Alexander [iii] the great. The Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) that followed ushered in a new imperial period, but these gains were part of the grand Hellenic scheme and did not provide the nation with a true empire carved out by Egypt’s armies. The Romans put an end to Egypt as an independent nation in 30 b.c.e.

Egyptian natural resources

The natural materials available to Egyptians in the Nile Valley and surrounding regions provided a vast array of metals, gems, and stones over the centuries. Nearby lands, easily controlled by Egyptian forces, especially in the period of the empire, held even greater resources, all of which were systematically mined or quarried by the various dynasties. These resources included:

Agate a variety of chalcedony (silicon dioxide), colored in layers of red or brown, separated by graduated shades of white to gray. Agate was plentiful in Egypt from the earliest eras. it was called ka or hedj and was found in the deserts with jasper. Some agate was brought from punt and nubia (modern sudan).

Alabaster a lustrous white or cream colored calcite (calcium carbonate), called shes by the Egyptians. Alabaster was quarried at hatnub and at other eastern Nile sites. The stone was used in jewelry making and in the construction of sarcophagi in tombs.

Amethyst a translucent quartz (silicon dioxide) that is found in various shades of violet. called hes-men, the stone was quarried at Wadi el-Hudi near aswan in the Middle Kingdom Period (2040-1640 b.c.e.) and at a site northwest of abu simbel.

Beryl a translucent, transparent yellow-green stone formed by aluminum-beryllium silicate. called wadj en bakh, the “green stone of the east,” beryl was brought from the coast of the Red sea during the Late Period.

Carnelian a translucent form of chalcedony that was available in colors from red-brown to orange. The stone was mined in the eastern and Nubian desert and was called herset. Carnelian was highly prized as rare and valuable and was used for heads, amulets, and inlays.

Chalcedony a translucent bluish white type of quartz (silicon dioxide) called herset hedji. Chalcedony was mined in the eastern desert, the baharia oasis, and the faiyum. Some chalcedony was also found in Nubia and in the sinai.

Copper a metal mined in the wadi Maghara and in the Serabit el-Khadim of the Sinai region. Called hemt, copper was also found in meteorites and was then called baa en pet.

Diorite a hard igneous rock, speckled black or white. Found in aswan quarries, diorite was called mentet and was highly prized.

Electrum a metal popular in the New Kingdom Period (1550-1070 b.c.e.) although used in earlier times. Electrum was a naturally occurring combination of gold and silver. it was fashioned into the war helmets of the pharaohs. it was called tjam (tchem), or white gold, by the Egyptians; the Greeks called it electrum. The metal was highly prized, particularly because silver was scarce in Egypt. Electrum was mined in Nubia and was also used to plate obelisks.

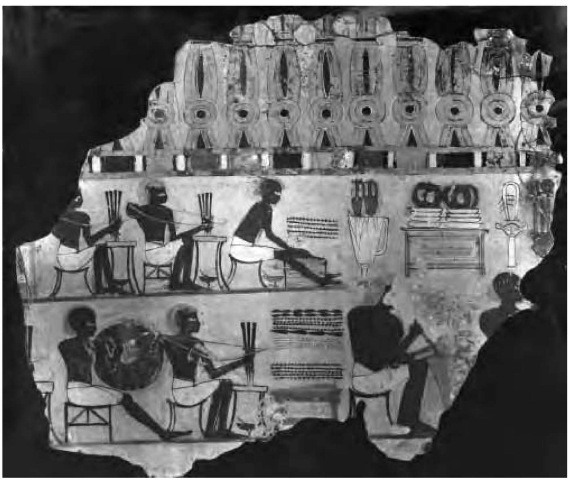

Skilled metal workers displayed on a painted wall using the rich metals exploited in various mines, part of Egypt’s rich natural resources. (Hulton Archive.)

Faience a decorative material fashioned out of fired quartz paste with a glazed surface. The crushed quartz (silicon dioxide), mined at Aswan or in Nubia, was coated either blue or green. A substitute for turquoise, faience was used for many decorative objects.

Feldspar an orange semiprecious stone now called “Amazon Stone.” When feldspar was a true green in color it was called neshmet. It was mined in the desert near the Red Sea or in the Libyan desert territories.

Garnet a translucent iron, or a silicate stone, mined near the Aswan area and in some desert regions.

Garnet was called hemaget by the Egyptians and was used from the Badarian Period (c. 5500 b.c.e.) through the New Kingdom Period. Gold the favorite metal of the Egyptians, who started mining the substance as early as the First Dynasty (2920-2770 b.c.e.). Gold was mined in the eastern deserts, especially at wadi abbad near edfu, and the Nubian (modern Sudanese) sites were the main sources. In later eras, other nations sent gold to Egypt as tribute. Gold was called nub or nub nefer when of the highest grade and tcham (tjam) when in the form of electrum.

Hematite an iron oxide that was opaque black or grayish black. The Egyptians called it bia and mined the substance in the eastern deserts and at Aswan and in the Sinai.

Jasper a quartz (silicon dioxide), available in green, yellow, and mottled shades, called khenmet or mekhenmet. Jasper was mined in the eastern deserts. The stone normally formed isis amulets and was used from the earliest eras.

Limestone an opaque calcium carbonate with varieties ranging from cream to yellow to pink to black. Found in the Nile hills from modern cairo to esna, the stone was called hedj in the white form. White limestone was quarried in the tureh area and was found as black in the eastern desert and pink in the desert near edfu.

Malachite an opaque, emerald green copper carbonate found near the copper mines of Serabit el-Khadim and the wadi maghara in the Sinai. Called shesmet or wadj, malachite was also found in Nubia and in the eastern desert.

Marble a crystalline limestone quarried in the eastern desert and used for statuary and stone vessels. Marble was called ibhety or behet by the Egyptians.

Mica a pearl-like potassium-aluminum silicate with iron and magnesium. Mica can be fashioned into thin sheets and was popular in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.). It was found in Nubia, and was called pagt or irgeb.

Obsidian a translucent volcanic glass that was probably quarried in Ethiopia (punt) or Nubia. Called menu kem when dark in color, obsidian was used for amulets and scarabs and for the eyes of statues.

Olivine a translucent magnesium iron silicate found in many Egyptian regions. Called perdjem, olivine was used for beads and decorations.

Onyx with sardonyx, varieties of chalcedony, found in the eastern desert and other Nile Valley sites. Onyx beads were used in Predynastic Periods (before 3000 b.c.e.) and became popular in the Late Period (712-332 b.c.e.).

Peridot a transparent green or yellow-green variety of olivine that was probably brought into Egypt. No mining sites are noted. Peridot was called perdjem or berget.

Porphyry an igneous rock formation of various shades. The black variety was used in early eras, and the purple variety was popular as amulets and pendants.

Quartz a hard opaque silicon dioxide quarried in Nubia and near Aswan. called menu hedj or menu kem, quartz was used for inlays, beads, and jewelry. Quartzite was found near heliopolis and at gebel el-ahmar.

Rock crystal a hard, glasslike quartz of silicon dioxide found in the Nile Valley between the Faiyum and the baharia oasis and in the Sinai region. It was called menu hedj, when white.

Silver a rare and highly prized metal in Egypt, called hedj, white gold. Silver was mined as electrum, called tcham or tjam in the wadi alaki, wadi miah, and in Nubia.

Steatite a magnesium silicate, called soapstone. Steatite was found in the eastern desert from the wadi hammamat to the wadi halfa and in Aswan. It was used extensively for scarabs and beads.

Turquoise a stone treasured by the Egyptians, found beside copper deposits in the Wadi Maghara and Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai. Called mefkat, turquoise was used in all eras, with the green variety preferred.

El-Bersha

A site opposite mallawi in the area of Middle Egypt where Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) tombs were discovered. There are nomarch burials in the area. Governors’ tombs were located in the necropolis at modern sheik said, and nearby meir has burial sites of El-Bersha nomarchs as well.

electrum

A metallic material called tjam, or white gold, and occurring as a natural combination of silver and gold. Popular in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) era, electrum was used for the war helmets of the militarily active pharaohs. Silver was scarce in Egypt, so this natural blend was highly prized.

Elephantine (Abu, Yebu)

An island at the northern end of the first cataract of the Nile near Aswan, called Abu or Yebu by the ancient Egyptians, the island and that part of Aswan served as the capital of the first nome of Upper Egypt and the cult center of the god khnum. The Elephantine Island was also revered as the source of the spiritual Nile. one mile long and one-third of a mile wide, Elephantine contained inscriptions dating to the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.). djoser (r. 2630-2611 b.c.e.) of the Third Dynasty visited the shrine of Khnum to put an end to seven years of famine in Egypt. His visit was commemorated in a Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) stela, the famed famine stela at sehel. The temple personnel of philae also claimed that Djoser gave them the island for their cult center.

A nilometer was placed on the Elephantine Island, as others were established in the southern territories and in the Delta. Ruins from a Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1783 b.c.e.) structure and others from the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 b.c.e.) were discovered on the island. When ‘ahmose of the Eighteenth Dynasty established the viceroyalty of nubia, the administrative offices of the agency were located on the Elephantine Island. Similar officials, given other names in various eras, had served in the same capacity in the region. The Elephantine Island was always considered militarily strategic.

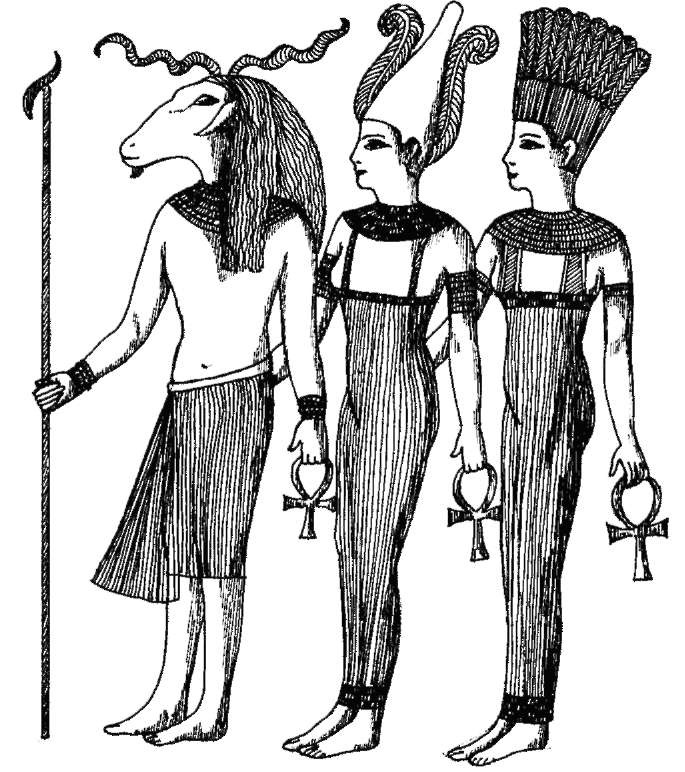

The deities of the Elephantine and the first cataract of the Nile—Khnum, Satet, and Atet.

A small pyramid dating to the Old Kingdom was also discovered on the island, and the Elephantine was supposedly noted for two nearby mountains, called Tor Hapi and Mut Hapi, or Krophi and Mophi. They were venerated in early times as “the cavern of Hopi” and the “Water of Hopi.” The territory was considered “the Storehouse of the Nile” and had great religious significance, especially in connection with the god Khnum and with celestial rituals. The temple of Khnum was erected on a quay of the island and was endowed by many pharaohs.

A calendar was discovered in fragmented form on the Elephantine Island, dating to the reign of tuthmosis iii (1479-1425 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The calendar was inscribed on a block of stone. This unique document was called the Elephantine calendar. Another inscription was discovered on a stela at the Elephantine. This commemorated the repairs made on a fortress of the Twelfth Dynasty and honors senwosret iii (r. 1878-1841 b.c.e.). The fortress dominated the island in that era, giving it a commanding sweep of the Nile at that location.

The Elephantine Papyrus, found on the island, is a document dating to the Thirteenth Dynasty (1783-1640 b.c.e.). The papyrus gives an account of that historical period. The Elephantine temple and all of its priestly inhabitants were free of government services and taxes.

The area was called “the Door to the South” and was a starting point for trade with Nubia.

Elkab (Nekheb)

A site called Nekheb by the Egyptians and one of the nation’s earliest settlements, dating to c. 6000 b.c.e. Elkab is on the east bank of the Nile, 20 miles south of esna. The site is across the river from hierakonpolis and is related to nearby Nekhen (modern Kom el-Ahmar). Predynastic palaces, garrisoned ramparts, and other interior defenses attest to the age of the site, which was sacred to the goddess nekhebet, the patroness of upper Egypt.

Elkab’s citizens rose up against ‘ahmose (r. 15501525 b.c.e.) when he started the Eighteenth Dynasty, and he interrupted the siege of the hyksos capital of avaris to put down the rebellion. The nomarchs of the area were energetic and independent. Their rock-cut tombs are in the northeast section of the city and display their vivacious approach to life and death. tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.) erected the first chapel to Nekhebet, finished by his successor amenhotep ii. The temple of Nekhebet had a series of smaller temples attached as well as a sacred lake and a necropolis. A temple honoring the god thoth was started by ramesses ii (r. 1290-1224 b.c.e.). The present Nekhebet shrine dates to the Late Period (712-332 b.c.e.). In the valley of Elkab shrines of Nubian deities were discovered, and in distant wadis a shrine to a deity named shesmetet and a temple of hathor and Nekhebet stand in ruins. The rock-cut tombs of ‘ahmose-pen nekhebet, ‘ahmose, son of ebana, and paheri are also on the site. Elkab also contains El-Ham-mam, called “the Bath,” which was dated to the reign of Ramesses II. His stela is still evident there. amenhotep iii (r. 1391-1353 b.c.e.) also erected a chapel there for the sacred Bark of Nekhebet.

El-Kula

A site on the western shore of the Nile north of hierakonpolis and elkab, the remains of a step pyramid were discovered there, but no temple or offertory chapel was connected to the shrine. The pyramid dates to the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.).

The “Eloquent Peasant” of Herakleopolis A commoner named khunianupu who farmed land in the wadi natrun, in the desert territory beyond the western Delta, probably in the reign of khety ii (Aktoy) of the Ninth Dynasty (r. 2134-2040 b.c.e.), Khunianupu decided to take his produce to market one day and entered the district called Perfefi. There he ran afoul of Djehutinakhte or Nemtynakhte, the son of a high-ranking court official, Meri. Djehutinakhte stole Khunianupu’s donkeys and produce and then beat him. The peasant took his complaints to Rensi, the chief steward of the ruler, when local officials would not aid him. Taken before a special regional court, Khunianupu pleaded eloquently, using traditional moral values as arguments. Rensi was so impressed that he gave the transcript of the testimony to the ruler. The court and ruler promptly punished Dje-hutinakhte by taking all his lands and personal possessions and awarding them to Khunianupu.

Called “the Eloquent Peasant,” announcing to the court officials the fact that “righteousness is for eternity,” Khunianupu eventually made his way into the royal court, where he was applauded and honored. The ruler supposedly invited Khunianupu to address his officials and to recite on state occasions. The popular account of Khunianupu’s adventures and sayings was recorded in the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1783 b.c.e.) and is included in four New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) papyri, now in Berlin and London. Such tales delighted the Egyptians, who appreciated the didactic texts of their literature and especially admired the independence and courage of the commoners, whether or not they were real people or fictitious characters.