over the centuries alien deities were brought to Egypt and more or less welcomed. Most of these gods were introduced by conquering alien forces, which limited their appeal to the Nile population. Some came as representatives of other cultures that were eager to share their spiritual visions. only a few of these deities attained universal appeal on their own merits. The Egyptians normally attached the deity to an existing one of long standing. The apis bull, for example, became serapis in the Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) and sokar became part of the ptah-Osiris cult. The major foreign gods introduced into Egypt are included in the preceding list of major deities of the nation.

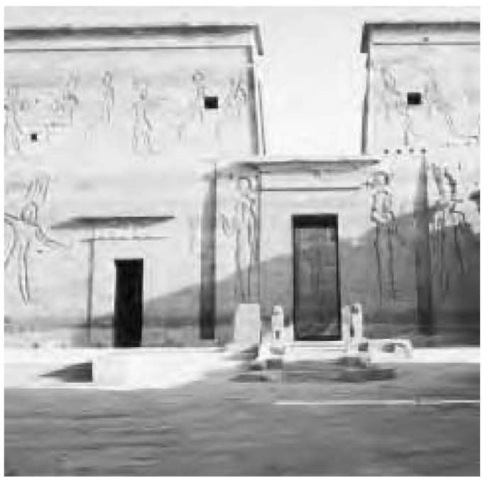

The opening to the temple of Isis at Philae and dating to the Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.), displaying the favored goddess, Isis.

Animal deities were also part of the cultic panorama of Egypt, serving as divine entities or as manifestations of a more popular god or goddess. The animals and birds so designated, and other creatures, are as follows:

ANIMALS

Creatures were believed by the Egyptians to represent certain aspects, characteristics, roles, or strengths of the various gods. sacred bulls were manifestations of power in Egypt in every era. The gods were called “bulls” of their reign, and even the king called himself the “bull” of his mother in proclaiming his rank and claims to the throne. The bull image was used widely in predynastic times and can be seen on maces and palettes from that period. The bulls a’a nefer, apis, buchis, and mnevis were worshiped in shrines on the Nile.

Rams were also considered a symbol of power and fertility. The ram of mendes was an ancient divine being, and amun of thebes was depicted as a ram in his temples in the New Kingdom. in some instances they were also theophanies of other deities, such as khnum.

The lion was viewed as a theophany, as was the cat, and the deities shu, bastet, sekhmet, and the sphinx were represented by one of these forms. The hare was a divine creature called Weni, or Wen-nefer. The hare was an insignia of re’s rising as the sun and also of the resur-rective powers of osiris. The jackal was anubis, the prowler of the graves who became the patron of the dead. As wepwawet, the jackal was associated with the mortuary rituals at assiut (or Lykonpolis) and in some regions identified with Anubis. Wepwawet was sometimes depicted as a wolf as well.

The pig, Shai, was considered a form of the god set and appeared in some versions of the topic of the dead, where it was slain by the deceased. The ass or the donkey, A’a, was also vilified in the mortuary texts. The mongoose or ichneumon, was called Khatru and was considered a theophany of re as the setting sun. The mouse, Penu, was considered an incarnation of horus.

The leopard had no cultic shrines or rites, but its skin was used by priests of certain rank. The baboon, Yan, was a theophany of thoth, who greeted Re each dawn, howling at the morning sun in the deserts. The elephant, Abu, was certainly known in Egypt but is not often shown in Egyptian art or inscriptions. ivory was prized and came from nubia. The hippopotamus, a manifestation of the god Set, was vilified. As tawaret, however, she also had characteristics of a crocodile and a lion. The bat was a sign of fertility, but no cultic evidence remains to signify that it was honored. The oryx, Maliedj, was considered a theophany of the god set.

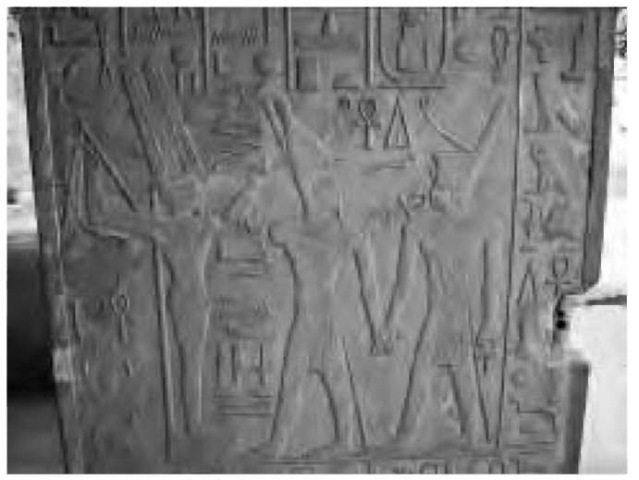

A pantheon of divine beings in Egypt, as displayed in the White Chapel at Karnak, including Amun and Min.

BIRDS

The bennu bird, a type of heron, was considered an incarnation of the sun and was believed to dwell in the sacred persea tree in heliopolis, called the soul of the gods. The phoenix, similar to the Bennu, was a symbol of resurrection and was honored in shrines of the Delta. The falcon (or hawk) was associated with Horus, who had important cultic shrines at edfu and at hierakonpolis. The vulture was nekhebet, the guardian of Upper Egypt. The goose was sacred to the gods geb and amun and called Khenken-ur. The ibis was sacred to the god Thoth at many shrines. The ostrich was considered sacred and its unbroken eggs were preserved in temples. The owl was a hieroglyphic character. See also bird symbols.

REPTILES

The turtle, shetiu, was considered a manifestation of the harmful deities and was represented throughout Egyptian history as the enemy of the god Re. The crocodile was sacred to the god sobek, worshiped in temples in the faiyum and at kom ombo in Upper Egypt. The cobra, wadjet, was considered an emblem of royalty and throne power. The cobra was also the guardian of Lower Egypt, with a special shrine at buto.

snakes were symbols of new life and resurrection because they shed their skins. One giant snake, methen, guarded the sacred boat of Re each night, as the god journeyed endlessly through the Underworld. apophis, another magical serpent, attacked Re each night. Frogs were symbols of fertility and resurrection and were members of the ogdoad at heliopolis. The scorpion was considered a helper of the goddess isis and was deified as selket.

FISH

The oxyrrhynchus (2) was reviled because it ate the phallus of the god Osiris after his brother, Set, dismembered his body.

INSECTS

The BEE was a symbol of Lower Egypt. The royal titulary “King of Upper and Lower Egypt” included the hieroglyph for the bee. The scarab beetle in its form of Khep-hri, was considered a theophany of the god Re. The image of a beetle pushing a ball of dung reminded the Egyptians of the rising sun, thus the hieroglyph of a beetle came to mean “to come into being.” The scarab beetle was one of the most popular artistic images used in Egypt.

SACRED TREES

The tamarisk, called the asher, was the home of sacred creatures, and the coffin of the god Osiris was supposedly made of its wood. The persea, at the site called Shub, was a sacred mythological tree where Re rose each morning at heliopolis and the tree upon which the king’s name was written at his coronation. The persea was guarded by the cat goddess, and in some legends was the home of the Bennu bird. The ished was a sacred tree of life upon which the names and deeds of the kings were written by the god Thoth and the goddess seshat.

The sycamore, nehet, was the abode of the goddess Hathor and was mentioned in the love songs of the New Kingdom. According to legends, the lotus, seshen, was the site of the first creation when the god Re rose from its heart. The god nefertem was associated with the lotus as well. The flower of the lotus became the symbol of beginnings. Another tree was the tree of heaven, a mystic symbol.

MYTHICAL ANIMALS

The saget was a mythical creature of uncertain composition, with the front part of a lion and a hawk’s head. its tail ended in a lotus flower. A painting of the creature was found in beni hasan, dating to the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.).

amemait, the animal that waited to pounce upon condemned humans in the judgment halls of osiris, had the head of a crocodile, the front paws of a lion, and the rear end of a hippopotamus. other legendary animals were displayed in Egyptian tombs, representing the peculiar nightmares of local regions. one such animal gained national prominence. This was the typhonean animal associated with the god set, depicted throughout all periods of Egypt.

The saget, a mythical creature found on a tomb wall in Beni Hasan and dating to the Twelfth Dynasty.

God’s Wife of Amun

A mysterious and powerful form of temple service that started in the first years of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1307 b.c.e.) and lasted until later eras. Queen ‘ahmose-nefertari, the consort of ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.), started the office of God’s Wife when she served as a priestess in the cult of amun. The office had its predecessor in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 b.c.e.) when queens conducted some temple rites.

hatshepsut (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.) not only assumed this role while a queen but as pharaoh groomed her daughter, neferu-re, to perform the same powerful office. During the time of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the God’s Wife was one of the chief servants of Amun at thebes. A relief at karnak depicts such a woman as destroying the enemies of “the God’s Father,” a male religious leader. The God’s Wife also held the title of “Chief-tainess of the harem,” designating her as the superior of the vast number of women serving the temple as adoratri-ces, chantresses, singers, dancers, and ritual priestesses. In Karnak the God’s Wife was called “the God’s Mother” or “the prophetess.”

Following the fall of the New Kingdom (1070 b.c.e.), the role of God’s Wife of Amun took on new political imperatives, especially in Thebes. sharing power with the self-styled “pharaohs” in the north, the Theban high priests of Amun needed additional accreditation in order to control their realms. The women were thus elevated to prominence and given unlimited power in the name of cultic traditions.

The daughters of the high priests of Amun, such as the offspring of pinudjem (2), were highly educated and provided with pomp, wealth, and titles. in the Twenty-first Dynasty (1070-945 b.c.e.) the God’s Wife of Amun ruled all the religious females in Egypt. amenirdis, nitocris, shepenwepet, and others held great estates, had their names enshrined in royal cartouches, lived as celebrities, and adopted their successors. By the era of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (712-657 b.c.e.) such women were symbolically married to the god in elaborate ceremonies. All were deified after death. The role of God’s Wife of Amun did not fare well in the face of foreign invasions and subsequently lost power and faded from the scene. Before that, however, the office was a political weapon, and some God’s Wives were removed from office, supplanted by new women who were members of an emerging dynastic line. The best known God’s Wives, or Divine Adoratrices of Amun, were Amenirdis i and ii, Nitocris, Shepenwepet I and II, and ankhesneferibre. Many were buried at medinet habu, and some were given royal honors in death as well as deification.

goose It was the symbol of geb, who was called the great cackler, the legendary layer of the cosmic egg that contained the sun. The priests of amun also adopted the goose as a theophany of Amun in the New Kingdom. The bird was sometimes called kenken-ur, the Great Cackler.

“go to one’s ka”

An ancient Egyptian expression for the act of dying. in some periods the deceased were referred to as having “gone to their kas in the sky.” See also eternity; ka.

government Basic tenets and autocratic traditions provided a uniquely competent level of rule in the Nile valley. The pharaoh, a manifestation of the god re while he lived and a form of the god osiris beyond the grave, was the absolute monarch of Egypt in stable eras. He relied upon nondivine officials, however, to oversee the vast bureaucracy, as he relied upon the priests to conduct ceremonies in the temples as his representatives.

under the rule of the pharaohs the various regions of Egypt were grouped into nomes or provinces, called sepat. These nomes had been designated in the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 b.c.e.), and each one had its own deity, totems, and lists of venerated ancestors. There were 20 nomes in Lower Egypt and 22 in upper Egypt (this number being institutionalized in the Greco-Roman Period). Each was ruled by a heri-tep a’a, called “the great overlord” or nomarch. The power of such men was modified in the reigns of strong pharaohs, but generally they served the central government, accepting the traditional role of “Being First under the King.” This rank denoted an official’s right to administer a particular nome or province on behalf of the pharaoh. such officials were in charge of the region’s courts, treasury, land offices, militia, archives, and storehouses. They reported to the vizier and to the royal treasury on affairs within their jurisdiction.

in general, the administrative offices of the central government were exact duplicates of the traditional provincial agencies, with one significant difference. in most eras the offices were doubled, one for upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt. This duality was carried out in architecture as well, providing palaces or administrative offices with two entrances, two throne rooms, etc. The nation viewed itself as a whole, but there were certain traditions dating back to the legendary northern and southern ancestors, the semidivine kings of the predynastic period (before 3,000 b.c.e.), and the concept of symmetry. Government central offices included foreign affairs, military affairs, treasury and tax offices, departments of public works, granaries, armories, mortuary cults of deceased pharaohs, and regulators of temple priesthood.

A prime minister, or vizier, reigned in the ruler’s name in most ages. Beginning in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 b.c.e.) or earlier, there were two such officials, one each for upper and Lower Egypt, but in some dynasties the office was held by one man. The role started early in the form of chancellor. Viziers in the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 b.c.e.) were normally related to the royal house. One exception was imhotep, the commoner who became high priest of the temple of ptah and vizier of djoser (r. 2630-2611 b.c.e.) in the Third Dynasty. The viziers heard all territorial disputes within Egypt’s borders, maintained a cattle census, controlled the various reservoirs and food supplies, collected taxes, supervised industries and conservation projects, and repaired all dikes. The viziers were also required to keep accurate records of rainfall (as minimal as it was) and to maintain current information about the expected levels of the Nile’s inundations. All documents had to have the vizier’s seal in order to be considered authentic.

Each vizier was normally assisted by members of the royal family or by aristocrats. This office was considered an excellent training ground for the young princes of each dynasty as it was designed to further the desires of the gods and the wishes of the pharaohs. Tax records, storehouse receipts, crop assessments, and a census of the human inhabitants of the Nile Valley were constantly updated in the vizier’s office by a small army of scribes. These scribes aided the vizier in his secondary role in some periods, that of the official mayor of thebes. In the New Kingdom the mayor of Thebes’s western side, normally the necropolis area, served as an aide, maintaining the burial sites on that side of the Nile. The viziers of both Upper and Lower Egypt saw the ruler each day or communicated with him on a daily basis. Both served as the chief justices of the Egyptian courts, giving all decisions in keeping with the traditional judgments and penalties.

The royal treasurer, normally called the treasurer of the god, had two assistants, one each for Upper and Lower Egypt. in most ages this official was also the keeper of the seal, although that position was sometimes given to the chancellor. The treasurer presided over the religious and temporal economic affairs of the nation. He was responsible for mines, quarries, and national shrines. He paid workers on all royal estates and served as the paymaster for both the Egyptian army and navy. The chancellor of Egypt, sometimes called the keeper of the seal, was assisted by other officials and maintained administrative staffs for the operation of the capital and royal projects. The judicial system and the priesthood served as counterbalances to the royal officials and insured representation of one and all in most dynastic periods.

In the Eighteenth Dynasty, ‘ahmose (r. 1550-1525 b.c.e.) established the viceroyalty of nubia (modern sudan), an office bearing the title of “King’s son of Kush.” Many officials previous dynasties had served in the same capacity at the elephantine Island at aswan, but ‘Ahmose made it a high-level rank. This officer controlled the affairs of the lands below the cataracts of the Nile, which extended in some eras hundreds of miles to the south. certain governors of the northlands were then appointed during the New Kingdom Period in order to maintain control of Asiatic lands under Egypt’s control as well as the eastern and western borders. some officials served also as resident governors of occupied territories, risking the loss of their lives when caught in rebellions by the conquered state.

The government of ancient Egypt was totally dependent upon the competence and goodwill of thousands of officials. The rulers of each age appear to have been able to inspire capable, decent men to come to the aid of the nation and to serve in various capacities with dedication and with a keen sense of responsibility. some families involved in various levels of government agencies, such as the amenemopet clan, served generation after generation. During certain ages, particularly in the waning years of the Ramessids of the Twentieth Dynasty (1196-1070 b.c.e.), officials became self-serving and corrupt. Such behavior had serious consequences for Egypt.

During the Third Intermediate Period (1070-712 b.c.e.), the government of Egypt was divided between the royal court and the religious leaders at Thebes. Women were given unique roles in Thebes, in the office of god’s wife of amun, or the Divine Adoratrices of Amun, or the power of the religious leaders. This office became part of the political rivalry of competing dynasties in the eras of divinity. piankhi (r. 750-712 b.c.e.) marched out of Nubia to conquer Egypt in order to put an end to such fractured government and to restore unity in the older traditions.

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664-525 b.c.e.) tried to restore the standards of government in Egypt but was faced with the Persians led by cambyses (r. 525-522 b.c.e.). The Persians placed Egypt under the control of a satrap, and the traditions were subject to the demands of the conquerors. The Twenty-eighth Dynasty (404393 b.c.e.) and the longer-lived Twenty-ninth (393380 b.c.e.) and Thirtieth (380-343 b.c.e.) Dynasties attempted to revive the old ways. The Persians returned in 343 b.c.e., only to be ousted by Alexander iii the great in 332 b.c.e.

The Ptolemaic Period (304-30 b.c.e.) restored the government of Egypt, bringing Hellenic concepts to the older forms and centralizing many aspects of rule. The internal feuds of the Ptolemies, and their refusal to accept Egyptians in their court or in their royal families, led to an isolation that made these rulers somewhat distant and alien to the average people on the Nile. Also, the laws were not the same for native Egyptians and the Greeks residing in the Nile Valley. The old ways, including the unabashed dedication of entire families to government service, were strained if not obliterated by the new political realities. The suicide of cleopatra vii in 30 b.c.e. put an end to the traditional Egyptian government for all time, as the nation became a territory of Rome.

Governors of the Northlands Officials of the New Kingdom Period (1550-1070 b.c.e.) governed three provinces of the eastern territories beyond the nation’s border regions and quite possibly some western border regions as well. The scope of Egypt’s empire was vast, ranging from just north of Khartoum in modern sudan to the Euphrates River. These officials had prominent roles during the era of Egypt’s empire. See also Egyptian empire.

Granicus

This was the site of the victory of Alexander iii the great (r. 332-323 b.c.e.) over the Persians. In Asia Minor, the river Granicus was the battleground between Alexander’s army of a reported 32,000 infantry and 5,100 cavalry troops, and the forces of darius iii codoman. Fresh from the victory on Granicus’s banks, the Greeks attacked sardis, Miletus, and Halicarnassus, all persian strongholds.

granite

A stone called mat by the Egyptians, much prized from the earliest dynasties and quarried in almost every historical period, hard granite was mat-rudjet. Black granite was mat-kemet, and the red quarried at aswan was called mat-en-Abu. Other important mines were established periodically, and granite was commonly used in sculptures and in reliefs. it served as a basic building material for Egyptian mortuary temples and shrines. Made into gravel, the stone was even used as mortar for fortresses, designed to strengthen the sun-dried bricks used in the construction process.

Greatest of Seers

A title used for some of the prelates of the temples at karnak, Memphis, and heliopolis, the name refers to rituals involving oracles, record-keeping, and probably astronomical lore.

Greece

This ancient peninsula on the Aegean sea was invaded around 2100 b.c.e. by a nomadic people from the north, probably the Danube Basin. The original inhabitants of the Greek mainland were farmers, seamen, and stone workers. These native populations were overcome, and the invaders merged with them to form the Greek nation, sharing mutual skills and developing city-states. The nearby Minoan culture, on crete, added other dimensions to the evolving nation.

By 1600 b.c.e., the Greeks were consolidated enough to demonstrate a remarkable genius in the arts and in government. Democracy or democratic rule was one of the first products of the Greeks. The Greeks also promoted political theories, philosophy, architecture, sciences, and sports and fostered an alphabet and biological studies. The Greeks traveled everywhere to set up trade routes and to spread their concepts about human existence. The Romans were themselves influenced by Greek art and thought and began to conquer individual Greek city-states. By 146 b.c.e., Greece became a Roman province.

In Egypt, the Greeks were in the city of naukratis, developed during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664-525 b.c.e.). Naukratis was a port city, offering trade goods from around the known world and pleasures that enticed visitors. The brother of the Greek poetess sappho lost his fortune and his health while residing in Naukratis and courting a well-known courtesan there. During the persian occupation of the Nile (525-404 b.c.e. and 343-332 b.c.e.), Naukratis and the Greek traders did not fare well. When alexander iii the great (r. 332-323 b.c.e.) defeated the persians and founded Alexandria, Naukratis suffered economically and politically. The last dynasty in Egypt, however, was Greek, founded by ptolemy i soter (304-284 b.c.e.) and ended with cleopatra vii (51-30 b.c.e.).

griffin (gryphen)

A mystical winged lion with an eagle head, used as a symbol of royal power in Egypt. niuserre, (Izi; r. 2416-2392 b.c.e.), of the Fifth Dynasty used the griffin in his sun temple at abu ghurob. The pharaoh is depicted in a relief as a griffin destroying Egypt’s enemies.

Ha He was an ancient deity of fertility, the patron of Egypt’s desert regions. In various historical eras, Ha was worshiped as a guardian of the nation’s borders and as a protector of the pharaoh and the throne. The seventh nome of Lower Egypt conducted cultic rituals in Ha’s honor.

Hakoris (Khnemma’atre, Achoris) (d. 380 b.c.e.)

Third ruler of the Twenty-ninth Dynasty

He reigned from 393 until his death. Hakoris was not related to the royal family of nephrites i, but upon the death of that ruler, he rose up against the designated son and heir of Nephrites i, psammetichus. Nephrites i, originally from sais, had established his capital at mendes. Hakoris took the throne there after a year of struggle and dated his reign from Nephrites I’s death. He also named his own son, another Nephrites, as his successor and set out to maintain the ideals of the dynasty.

Hakoris’s reign witnessed considerable rebuilding and restoration within Egypt, and he kept the persians at bay while he lived. concluding a treaty with Athens, Hakoris was able to field a mercenary army with Greek veterans in times of peril. The Athenian general, khabrias, aided him, and the Egyptian general, Nabktnenef (nectanebo i) headed native troops. In Hakoris’s eighth regnal year, Nabktnenef put down a troublesome revolt.

artaxerxes ii of Persia had been struggling with Greece but made peace in 386 and turned his attention to Egypt. In 385 and 383 b.c.e. the Persians attempted to subdue Hakoris but were stopped by the renewed Egyptian navy. Hakoris died in 380 b.c.e. and was succeeded by his son, nephrites ii, but General Nabktnenef overthrew the heir and took the throne as Nectanebo i, starting the Thirtieth Dynasty

Halicarnassus

A city now called Bodrum on the modern Bay of Gokova in Turkey, during the reign of xerxes i (486-466 b.c.e.), the city was ruled by Artemisia, a woman, who served also as a naval tactician. she also aided Xerxes as a counselor. herodotus was a native of Halicarnassus, and Mausolas was a ruler of the city. Alexander iii the great took Halicarnassus, and the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt (304-30 b.c.e.) ruled it during the second century b.c.e., losing it eventually to the Romans.

Halwan (Helwan)

A site near saqqara in the el-Saff territory, which is located on a plateau above the Nile River and serves as a southern suburb of modern cairo, Halwan has been inhabited since prehistoric times (before 3,000 b.c.e.) and has cemeteries containing First Dynasty (2920-2700 b.c.e.) tombs as well. The tombs have walls manufactured out of brick and hard stone, and they are considered examples of the first use of such stone in monumental architecture on the Nile. Magazines for storage and staircases demonstrate a skilled architectural design. The ceilings were fashioned with wooden beams and stone slabs. The halwan culture is classified as part of the Neolithic Age of Egypt. There were 10,000 graves at Halwan, and signs of mummification processes are evident, all performed in a rudimentary manner. Linen bandages soaked in resin, stelae, and statues were also found on various sites in the area.

“Hanging Tomb”

Called Bab el-Muallaq and located south of deir el-bahri on the western shore of thebes.

The site might be “the High Place of Inhapi” of legend, reportedly a safe haven used originally for the royal mummies in the Deir el-Bahri cache. It was so named because of its position in the cliffs.

Hapi (1) (Hopi, Hap, Hep)

A personification of the nile and a patron of the annual inundation, Hapi was the bearer of the fertile lands, nourishing both humans and the gods of Egypt. The husband of the goddess nekhebet, Hapi was particularly honored at the first cataract of the Nile. In reliefs he is depicted as a bearded man, normally painted blue or green, with full breasts for nurturing. Hapi sometimes is shown with water plants growing out of his head. He is pictured often as a double figure, representing the Blue and White Nile. Hymns in honor of Hapi speak of the Nile in cosmic terms, provoking images of the river as the spiritual stream that carried souls to the Tuat, or Underworld. These hymns express the nation’s gratitude for the annual flood times and the lush fields that resulted from the deposited effluvium and mud. Annual festivals were dedicated to Hapi’s inundation.

Hapi (2)

A divine son of the god horus who is associated with the funerary rites of Egypt, he was one of the four guardians of the vital organs of the deceased in the canopic jars in tombs. Hapi was guardian of the lungs, and on the canopic jars this deity was represented by the head of a baboon. The other sons of Horus involved in canopic rituals were duamutef, qebehsennuf, and imsety.

Hapuseneb (fl. 15th century b.c.e.)

Temple official of the Eighteenth Dynasty

He served tuthmosis ii (r. 1492-1479 b.c.e.) and hat-shepsut, the queen-pharaoh (r. 1473-1458 b.c.e.). Hapuseneb was the first prophet of amun at thebes and the overseer of all of the Amunite priests of Egypt. in his era the cult of Amun was elevated to the supreme rank as Egypt’s commanding deity. A noble by birth, and related to the royal clans through his mother Ah’hotep, Hap-useneb supported Queen Hatshepsut when she took the throne from the heir, Tuthmosis III (1479-1425 b.c.e.). His aid pledged the Amunite temples to her cause and served as a buffer against her enemies. He directed many of her building projects and served as her counselor. Hapuseneb owned a great deal of land in both upper and Lower Egypt. He was buried on the western shore at thebes, and after his death was honored as well with a shrine at gebel el-silsileh.

harem (1)

This was the household of lesser wives of the king, called the per-khenret in ancient Egypt, a highly organized bureaucracy, functioning primarily to supply male heirs to the throne, particularly when a male heir was not born to the ranking queen. The earliest evidence for a harem dates to the Early Dynastic Period (2920-2575 b.c.e.) and to the tombs of several women found beside that of djer (r. 2900 b.c.e.) in abydos. These women were obviously lesser ranked wives who provided additional birthing opportunities. some of these wives were also given to the pharaohs by nome clans, as a sign of alliance. These lower ranked wives and concubines lived in the harem. By the Sixth Dynasty (2323-2150 b.c.e.), the institution was presided over by a queen and included educational facilities for the children of the royal family and those of important officials.

In the reign of amenhotep iii (1391-1353 b.c.e.) of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the harem was located at malkata, his pleasure domain on the western bank at thebes. akhenaten had a harem at ‘amarna (1353-1335 b.c.e.) and the administration of this enclave has been well documented. Harems of this period had overseers, cattle farms, and weaving centers, which served as training facilities and as a source for materials. Harems employed scribes, inspectors, and craftsmen as well as dancers and musicians to provide entertainment for royal visits. Foreign princesses were given in marriage to the Egyptian rulers as part of military or trade agreements, and they normally resided in the harem. in some eras, harem complexes were built in pastoral settings, and older queens, or those out of favor, retired there. in ramesses ii’s reign (1290-1224 b.c.e.) such a harem retirement estate was located near the faiyum, in mi-wer (near Kom Medinet Ghurob), started by tuthmosis iii (r. 1479-1425 b.c.e.).

The harem could also be a source of conspiracy. The first such recorded plot dates to the old Kingdom and the reign of pepi i (2289-2255 b.c.e.). An official named weni was commissioned to conduct an investigation of a queen, probably amtes. Because the matter was so confidential, Weni left no details as to the circumstances surrounding the investigation. A second harem intrigue occurred in the reign of amenemhet i (1991-1962 b.c.e.) of the Twelfth Dynasty. Amenemhet had usurped the throne, and an attempt was made on his life, as he recorded himself in his instructions (also called The Testament of Amenemhet). The ruler fought hand to hand with the attackers, later stating that the plot to kill him stemmed from the harem before he named senwosret i (the son to whom he addressed his advice) his coruler. Amenemhet died while senwosret was away from the capital, giving rise to the speculation that he was finally assassinated by another group of plotters. There is no evidence proving that he was murdered, but the Tale of sin-uhe the sailor, dating to that period, makes such a premeditated death a key element.

The third harem plot, the best documented, took place in the reign of ramesses iii (1194-1163 b.c.e.) of the Twentieth Dynasty. The conspiracy was recorded in the judicial papyrus of turin and in other papyri. tiye (2), a minor wife of Ramesses iii, plotted with 28 high-ranking court and military officials and an unknown number of lesser wives of the pharaoh to put her son, pentaweret, on the throne. A revolt by the military and the police was planned for the moment of Ramesses Ill’s assassination. With so many people involved, however, it was inevitable that the plot should be exposed.

The coup was perhaps successful in its purpose. Ramesses iii is believed to have died soon after. He commissioned a trial but took no part in the subsequent proceedings. The court was composed of 12 administrators and military officials. Five of the judges made the error of holding parties with the accused women and one of the men indicted during the proceedings, and they found themselves facing charges for aiding the original criminals.

There were four separate prosecutions. Tiye, who had plotted in favor of her son, pentaweret, was executed in the first proceeding with 20 others, members of the police, military, and palace units that were supposed to rise up in support of pentaweret when Ramesses iii died. in the second prosecution, six more were found guilty and were forced to commit suicide in the courtroom. pentaweret and three others had to commit suicide as a result of the third prosecution. During the final episode, several judges and two officers were convicted. Three of these judges lost their ears and noses. one was forced to commit suicide and one was released after a stern reprimand.

harem (2)

This was the name given to the women who served in the temples of karnak and luxor as Dedicated Adoratrices of the deity Amun. Taking roles as chanters, adorers, priestesses, etc., these women were in full-time employment or served as volunteers. The god’s wife of amun, a rank reserved for princesses, headed the god’s vast “harem,” thus regulating such service. The women were involved in such duties as officials of the temple until the end of the Third intermediate period (1070-712 b.c.e.). Many continued in the roles throughout the remaining historical periods of the nation.