In This Topic

- Seeing the advantages to growing lady’s slippers

- Helping your lady’s slipper to feel at home Choosing the right lady’s slipper for you

Lady’s slippers are some of the easiest orchids to grow and among the most rewarding orchids you’ll find, making them a great orchid for beginners. They present a wide range of strikingly colored, frequently glossy flowers in myriad shapes. Some have petals that are elegantly twisted, while others are marked with hairs and warts. All slipper orchids are noted for very-long-lasting blooms — the flowers usually last six to eight weeks. Many slipper orchids have gorgeous marbled foliage, which makes them stunningly beautiful, even when they aren’t in bloom. Collectors of slipper orchids tend to be a fanatic lot — and it’s easy to see why.

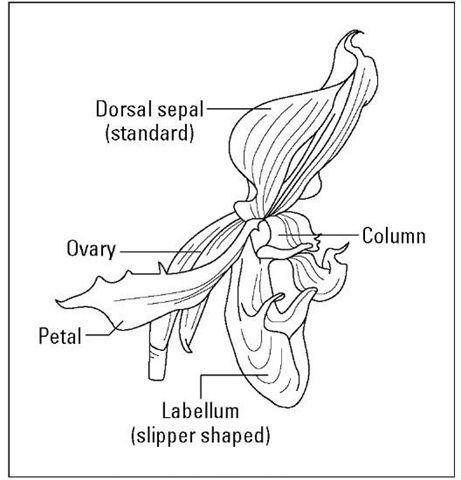

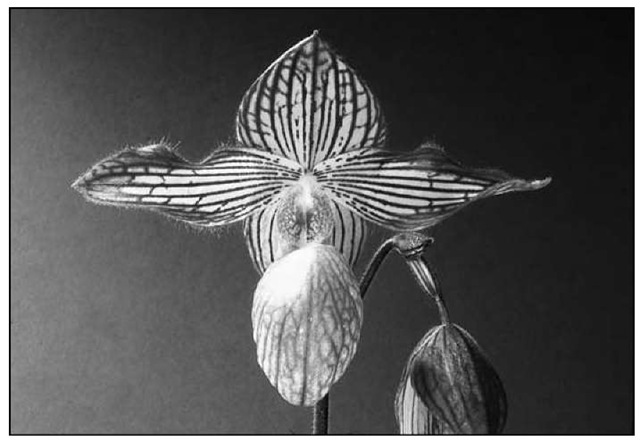

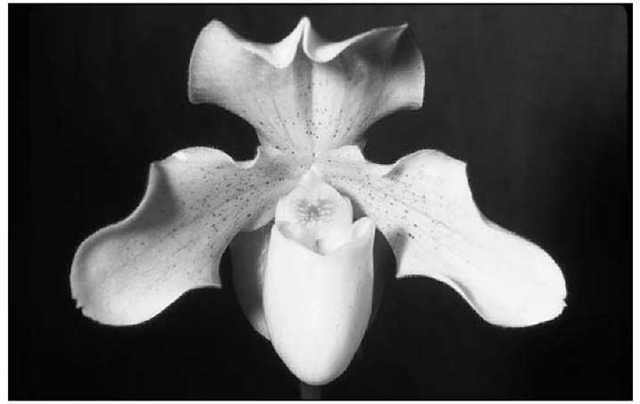

The official name of this group is Paphiopedilum ‘Asian Lady’s Slipper,’ but you’ll probably hear them referred to as lady’s slippers or just plain slipper orchids — though they’re anything but plain. These orchids got their common name because of their pouchlike lip, or labellum, which resembles a lady’s slipper (see Figure 12-1).

In this topic, I introduce you to the world of lady’s slipper orchids — giving you some slipper-specific growing tips, some suggestions of varieties to buy, and some tips on which hybrids are your best bet.

Figure 12-1: The parts of a lady’s slipper orchid.

Slipping into a Lady’s Slipper

Lady’s slippers are wonderful flowers for beginning orchid growers. In this section, I fill you in on why you should consider growing one, what kind of environment to give a lady’s slipper after you bring it home, and how best to encourage your lady’s slipper to bloom.

Seeing what lady’s slippers have to offer

- Lady’s slippers are extremely popular among orchid growers — professional and amateur alike — because

- They display a great diversity of flower forms. Many are easy to grow. Many have beautiful foliage.

- Most have very-long-lasting flowers, usually lasting many weeks.

Giving your lady’s slipper a good home

Although lady’s slipper orchids are found in cold climates in North America, the ones that are most commonly grown indoors are the ones from the old-world tropics, like Southeast Asia. Almost all lady’s slippers grow well in average home temperatures — 65°F to 75°F (18°C to 24°C) during the day, and 55°F to 60°F (13°C to 18°C) during the evening — and have modest humidity requirements.

Some of the lady’s slippers are among the least demanding orchids when it comes to light, so they’re very adaptable to growing on windowsills or under lights.

Getting lady’s slippers to bloom

Slipper orchids are some of the easiest of all orchids to grow and bloom. That said, you can’t force these plants to flower if they’re not mature or if it isn’t their normal time of year to bloom. If your slipper orchid hasn’t bloomed in over a year, and it needs a little nudging, try this three-step method:

1. Grow your lady’s slipper in a little brighter spot.

If you don’t see the flower buds forming in six to eight weeks, keep it in this same location and move to Step 2.

2. Drop the temperature at night about 20°F (12°C) cooler than the daytime temperature.

If you don’t see buds forming in six to eight weeks, move it back to its regular growing temperature and then move to Step 3.

3. Let your lady’s slipper get a little drier than usual for six to eight weeks.

Straight from Nature: Bumps, Warts, Hairs, and All

Lady’s slipper species, which is what the plants are called as they come from the wild, display an exotic array of nature’s work. In the following sections, I give you a sampling of some of the easier-to-grow of the more than 60 commonly found lady’s slipper species.

Paphiopedilum bellatulum

Paphiopedilum bellatulum is not the easiest of all lady’s slippers, but it isn’t difficult if you just keep in mind that these plants prefer to be a little cooler and drier than the other lady’s slippers.

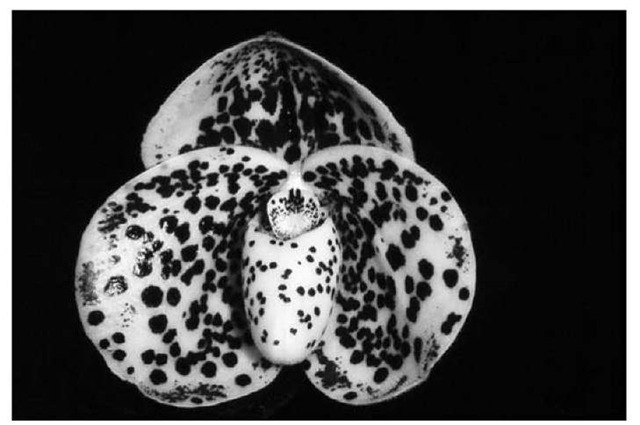

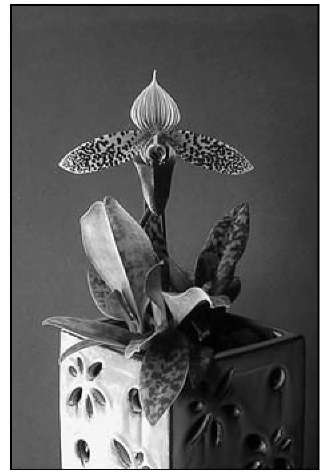

This orchid is commonly called the “egg-in-a-nest orchid,” because that’s what its white pouch looks like as it’s surrounded by its rounded-white with burgundy-spotted petals. The thick leaves of this dwarf grower (only a few inches high) are beautifully patterned (see Figure 12-2).

Figure 12-2: Paphiopedilum bellatulum is a compact-growing horticultural gem.

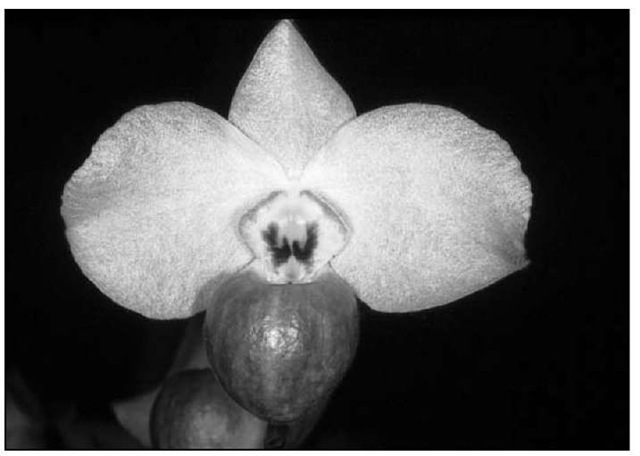

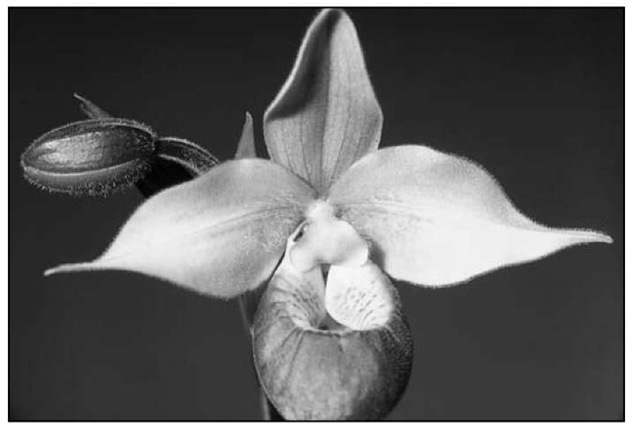

Paphiopedilum callosum

Paphiopedilum callosum was the first lady’s slipper orchid that I grew, over 30 years ago. I had imported it from Thailand, and seeing it bloom for the first time was a thrill! It continued to perform on a regular basis.

This orchid is one of the simplest to grow and one of the most dependable to bloom. It comes in various flower shapes and color combinations of burgundy and green (see Figure 12-3). Its strong constitution and attractiveness make it very popular as a parent in hybridizing. This species is quick to multiply, so it’ll give you a large plant in a relatively short time.

Figure 12-3: Paphiopedilum callosum is as dependable a bloomer as you can find.

Paphiopedilum delenatii

Paphiopedilum delenatii is a delicate-looking, prized beauty. I used to find this orchid a bit on the temperamental side when it came to growing. Fortunately, the newer forms on the market today have more vigor and aren’t finicky as they once were. Mine blooms dependably each spring, bearing one or two elegant light pink petal flowers with a darker pink pouch (see Figure 12-4). Unlike most lady’s slippers that are scentless, this one possesses a subtle and delightful citrus fragrance.

Paphiopedilum dianthum

Paphiopedilum dianthum is a Chinese species that is relatively easy to grow, needing just a modest amount of light — mine blooms consistently every year. This orchid puts on a floral display for many weeks. Its flowers have twisted green petals and a burgundy-brown pouch, topped with a white dorsal. The 12- to 16-inch (30- to 40-cm) leaves of this slipper orchid are glossy green with a leathery texture (see Figure 12-5).

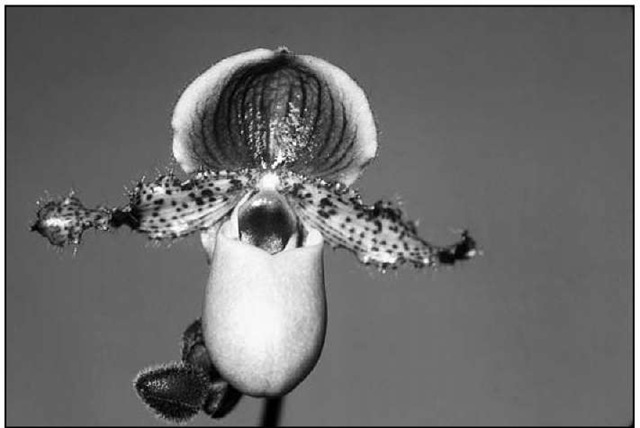

Paphiopedilum fairrieanum

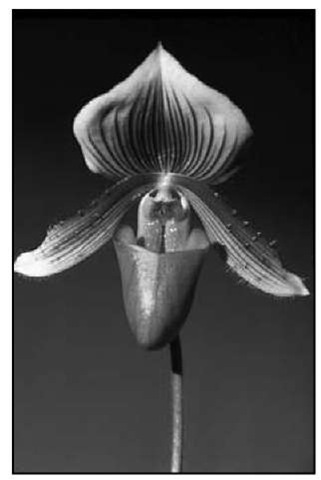

The upswept petals and prominently marked dorsal of the Paphiopedilum fairrieanum present an exotic display (see Figure 12-6). This is another slipper orchid that is undemanding and can be quickly grown into a nice-sized plant. The most common form of this species has petals striped in greens and purples, but there are other color combinations that are yellow, dark red, and green —some have longer and narrower petals than the standard type. The albino form — green and white — is especially enchanting.

Figure 12-4: Paphiopedilum delenatiidisplays special elegance.

Figure 12-5: Paphiopedilum dianthum requires a very modest amount of light to grow and flower well.

A conservation success story

The history of the discovery and collection of orchids is littered with dismaying accounts of man’s destruction of habitats resulting from the careless and greedy collection of these plants from their native lands. Encouragingly, this isn’t always the case.

Paphiopedilum delenatii was first discovered in Vietnam in 1913 by a French officer. From the plants collected and exported at that time, only a few survived. One of them was grown by the famous French orchid nursery of Marcel Lecoufle, who successfully produced seeds from it. Shortly after, no more of the plants of this species were able to be found in the wild. For generations, all the plants of Paphiopedilum delenatii that were known were those resulting from these seedlings form Marcel Lecoufle!

Now this is a commonly grown and admired species.

Figure 12-6: Paphiopedilum fairrieanum hails from the cliffs of India and Bhutan.

An orchid with a history of intrigue

For over 50 years during the late 1800s and early 1900s, the source of this treasured orchid, Paphiopedilum fairrieanum, remained a mystery. The only plant that was known had shown up in a shipment of unknown origin. In 1904, the famous orchid purveyor in England, Frederick Sander, offered a reward of £1,000 for anyone leading to the rediscovery of this orchid. This bounty was enough to bring results as new plants were discovered and exported from Bhutan and sold in the English orchid auctions for princely sums. Now this same horticultural gem is commonly available for indoor gardeners worldwide to enjoy at a very modest price.

Keeping the plant on the cooler, dryer side for six weeks during the winter will encourage it to put on its spring flower show.

Paphiopedilum glaucophyllum

Paphiopedilum glaucophyllum rewards you with a very long blooming period — its flowers open one at a time, so the plant can be in bloom for months. It has attractive blue-green foliage. Its fuzzy petals — green dorsal edged in white — and rosy pink pouch make quite a nice presentation (see Figure 12-7).

Figure 12-7: Paphiopedilum glaucophyllum is easy to grow and will reward you with months of bloom.

Paphiopedilum hirsutissimum

Paphiopedilum hirsutissimum is another distinctive Asian beauty. It has long, lance-shaped, light-green foliage with purple-and-green-marked flowers with wavy edges (see Figure 12-8). It’s a vigorous grower but can sometimes be a reluctant bloomer.

Some growers have found if they drop the night temperature to 40°F to 45°F (4°C to 7°C) for several weeks in early winter, this may trigger flowering.

Figure 12-8: Paphiopedilum hirsutissimum grows in cooler spots than many of the other slipper orchids.

Paphiopedilum spicerianum

Definitely one of my favorites, Paphiopedilum spicerianum puts on a dramatic display. Its shining white dorsal marked with a purple vertical strip up its center, surrounded by the shades of green and brown on its petals and pouch, make it a showstopper. Its white dorsal is so special that this slipper has been used frequently as a parent in breeding to impart this beautiful feature to its progeny. Turn to the color photographs in the center of this topic for an example of Paphiopedilum spicerianum.

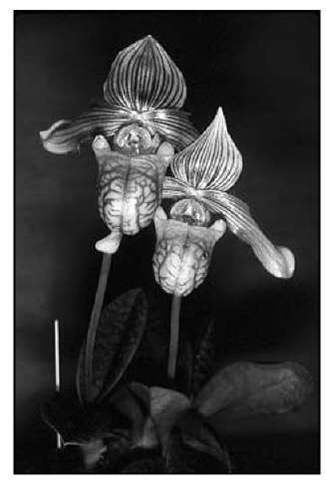

Paphiopedilum sukhakulii

Some commercial growers lament that Paphiopedilum sukhakulii grows so quickly that they can’t keep up with it. This is a “problem” that most amateur orchid growers would love to have! Paphiopedilum sukhakulii is a compact grower with prominently and attractively marked foliage. Figure 12-9 illustrates my plant in a 4-inch (8-cm) pot.

Its flowers offer a green-and-white-striped dorsal, wide-horizontal petals that are green with mahogany spots and sprinkled with warts and hairs, all set off with a dark maroon pouch. This species quickly forms a good-sized plant with many leads, and it frequently blooms more than once a year. See the color photographs in the center of this topic for another example.

Figure 12-9: Paphiopedilum sukhakulii is a compact-growing, undemanding, high-performing slipper orchid.

Paphiopedilum venustum

Described in the early 1800s, Paphiopedilum venustum was the first of the lady’s slippers to be cultivated. Its handsome foliage makes it a standout even before its flowers, with distinctly veined lips and brightly colored petals, put on their show (see Figure 12-10). Paphiopedilum venustum is found in many different color forms.

Letting the plants get a little drier in the winter than you would in the summer increases their likelihood of flowering.

Figure 12-10: Paphiopedilum venustum is easily identified by its prominently veined lip or pouch.

One Step Removed from Nature: Primary Hybrids

Primary hybrids are the results of crossing (mating) two different species, like the ones mentioned in the preceding sections, to create a new plant. In doing this, exciting new forms of orchids are created. The crossing process started in the 1800s and is continuing at full speed today. As new species are being discovered or better forms of the same species are showing up, the orchid breeder gets more new genetic material to play with. The results of some of these efforts are quite impressive.

The goals of breeding vary within the group, but the main purpose is to

- Expand the color range.

- Vary the flower shapes.

- Make the flowers larger.

- Create a new “look.”

- Make the plants more compact.

- Make the plants more vigorous and easier to bloom.

In the following sections, I introduce you to just a handful of some of the many great successes. It’s fun to look at the parents and guess what the offspring will look like. There are plenty of surprises!

Some superior primary hybrids

These primary hybrids do their parents proud! Each of the following hybrids carries the good looks from its parents, but also adds its own new beauty and, in most cases, is more vigorous and easier to grow than either of the parents:

Paphiopedilum Angela: From the photo of this variety (see Figure 12-11), can you take a guess what one of its parents is? Do you see the exotic touch from one of its parents, Paphiopedilum fairrieanum (refer to Figure 12-6)? Its other parent is a darling white species that can be a bit difficult to grow well, Paphiopedilum niveum. When these two are mated, the offspring — Paphiopedilum Angela — is a delightful compact-growing plant, easier to grow like Paphiopedilum fairrieanum, but with the delicate white coloring from Paphiopedilum niveum.

Paphiopedilum Armeni White: Another good choice, this hybrid has very-dark-green patterned foliage and a large, soft-white flower.

Paphiopedilum Delophylum: This is an enchanting orchid with soft pink flowers, borne sequentially, on compact plants with attractively marked foliage.

Figure 12-11: Paphiopedilum Angela has a charming flower on a compact plant.

Paphiopedilum Fumi’s Delight: This is another case where two fetching but sometimes-tricky-to-grow species, when mated or crossed, yield a more vigorous offspring than either of the parents. One parent has a bright yellow flower (Paphiopedilum armeniacum); the other (Paphiopedilum micranthum) has a pink bloom. The offspring of these parents have flowers varying in color from creamy yellow to light pink (see Figure 12-12).

Paphiopedilum Ho Chi Minh: This is a new hybrid that is highly sought after. One of its parents is Paphiopedilum vietna-mense, a gorgeous dark pink slipper recently discovered, and the other is Paphiopedilum delenatii, an elegant soft pink flowered slipper (refer to Figure 12-4). This should be a winning match.

Paphiopedilum Gloria Naugle: This orchid is the result of crossing the largest-flowered and king of the slippers, Paphiopedilum rothschildianum, with Paphiopedilum micranthum. This hybrid inherits the bold stripes from Paphiopedilum rothschildianum and the hot pink from its other parent. The results are quite striking (see Figure 12-13).

Paphiopedilum Magic Lantern: One of the most popular newer primaries, Magic Lantern, is a dependable grower and bloomer and its dark pink to red-pink flowers always elicit oohs and ahs.

Figure 12-12: Paphiopedilum Fumi’s Delight is a popular primary hybrid.

Figure 12-13: Paphiopedilum Gloria Naugle presents an arresting picture.

Paphiopedilum Makulii: Although not literately a primary, this orchid is very close to it. This hybrid takes the dramatic petal markings from Paphiopedilum sukhakulii (refer to Figure 12-9) and combines them with the darker flower colorations of its Maudiae hybrid cousins (see the section “Marvelous Maudiaes,” later in this topic). This lady’s slipper is a snap to grow.

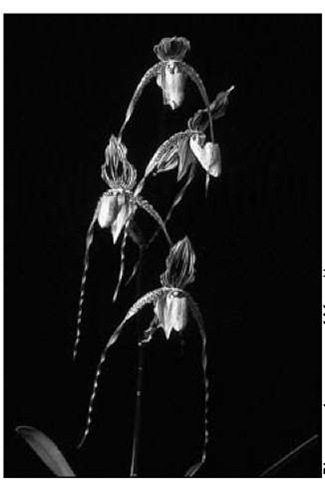

Paphiopedilum Saint Swithin: Another hybrid — with one of its parents being the huge Paphiopedilum rothschildianum — this orchid is combined with another impressive bloomer, Paphiopedilum philippinense, which has a smaller growth habit and a history of being easier to flower. The result is striped flowers with dangling twisted petals — nothing less than extraordinary (see Figure 12-14). This is a larger lady’s slipper than some of the others, but it’s well worth the growing space! This one does require more light that the other slippers mentioned earlier. Grow in the same medium to bright light you provide cattleyas and it will be happy.

Paphiopedilum Transvaal: This is a classic beauty first bred in 1901 and still popular today. It takes its stateliness from Paphiopedilum rothschildianum but reduces its size and adds ease of blooming from its other parent, Paphiopedilum cham-berlainianum. This is another orchid that likes it bright, like Saint Swithin.

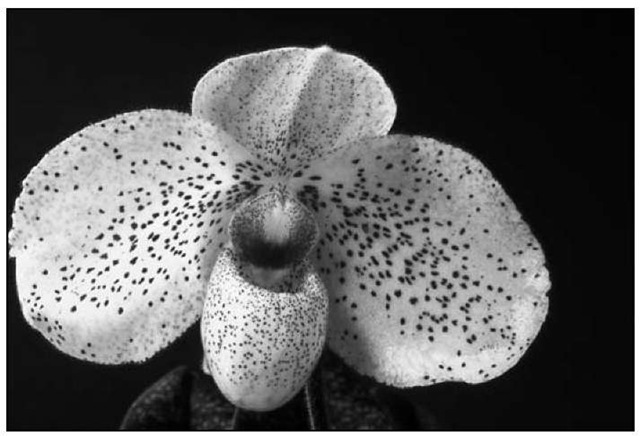

Paphiopedilum Vanda M. Pearman: One of the most popular of all primary hybrids, Vanda M. Pearman has large light pink flowers dusted with dark burgundy spots, all shown off against thick, leathery, gorgeously marbled foliage (see Figure 12-15). This is a must-have lady’s slipper.

Figure 12-14: Paphiopedilum Saint Swithin puts on a spectacular show!

Figure 12-15: Paphiopedilum Vanda M. Pearman is admired for its elegant flower and attractive foliage.

Marvelous Maudiaes

What a fabulous group of lady’s slippers these are. The word Maudiae is the name given to one of the first hybrids made, in 1901, between Paphiopedilum callosum (see the color photographs in the center of this topic for an example) and Paphiopedilum lawrenceanum. Paphiopedilum Maudiae and its offspring are noted for their exceptional vigor, ease of blooming (sometimes more than once a year), undemanding growing requirements, gorgeous foliage, and striking, gloriously colored flowers. They are found in three major color groups or combinations, covered in the following sections.

Green-and-whites

Green-and-white Maudiaes are occasionally referred to as albinos because they lack the more commonly found red pigment. There is a simple timeless elegance to these flowers. They’re highly revered in Europe as cut flowers.

Some super clones exist within this group like Paphiopedilum Claire de Lune ‘Edgard van Belle’ AM/AOS (see Figure 12-16). Its regal name fits its aristocratic look. It’s huge impressive flower stands proudly above dark green handsome foliage. I received a division of this plant from a now deceased dear friend, Frances Nelson. It’s a treasured memory of him, and I’ve shared divisions of it with special friends. It’s a vigorous grower that still wins ribbons for me at orchid shows.

Another famous clone is Paphiopedilum Maudiae ‘The Queen’ AM/AOS. If you’re fortunate to find these clones at a price you can live with, snatch them up. If they’re too pricey for you at this point, try any of the standard green-and-white Maudiaes. None of them will disappoint you.

Figure 12-16: Paphiopedilum Claire de Lune ‘Edgard van Belle’ AM/AOS is a prize for anyone’s orchid collection.

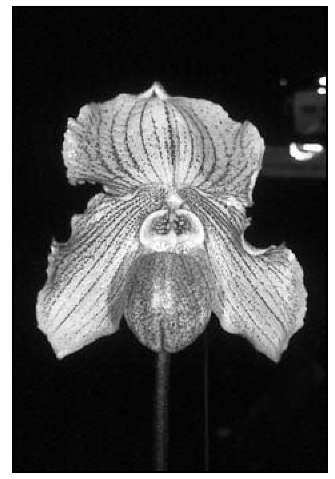

Coloratums

This group is typified by a large dorsal and petals displaying streaks of purple in the flowers. The flower shape of this type looks very similar to the green-and-white Maudiae but has much more red and burgundy markings (see Figure 12-17). Many times the dorsal is larger and rounder.

Figure 12-17: A coloratum type. Notice the wide dorsal and the streaks of darker color throughout the flower.

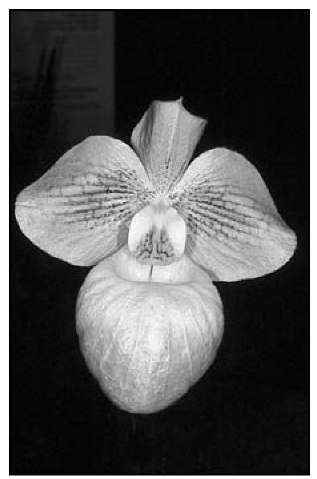

Vinicolors

The flowers of this type look like they’ve been varnished. They’re a rich dark red or purple and have many admirers. This is probably the most sought after form of the Maudiae types. Their solid burgundy to mahogany blossoms shine (see Figure 12-18).

There are many good vinicolor varieties out there — too many to list. If you’re lucky enough to actually see them in bloom, you can choose the ones that you like best. Unfortunately, because they’re popular and are quickly snatched up, you may be forced to pick out blooming-size plants or ones in bud so you aren’t sure what they’ll look like when they bloom.

Here are two ways to increase your odds for buying the best:

Check out their parents. Several orchid parents have a good reputation for producing high-quality offspring. Here are some to look for:

• Black Cherry

• Blood Clot (Ugh! What a name!)

• Eric Meng

• Laser

• Macabre

• Raisin Pie

• Red Fusion

• Red Glory

• Ruby Peacock

Look at the color of the leaves, flower stem, and bud. The darker the purple in the newest leaves, the undersides of the leaves, the flower stem, and the buds, the greater the likelihood that the flower will also carry this dark pigment.

Figure 12-18: A vinicolor showing solid dark coloration over the entire flower.

Huge and round: Modern hybrid lady’s slippers

These lady’s slippers are sometimes called “bulldogs” or “toads.” To tell you the truth, I don’t know how they got branded with such odd nicknames! They look nothing like these two creatures to me.

Another moniker for them is complex hybrids, and this makes sense, because their parentage is very convoluted, many times consisting of 20 or more parents.

All the orchids in this group have plain green foliage and most of their flowers are huge and round (see Figure 12-19). They’re basically categorized by their flower colors: spotted, green, white, yellow, red, pink, and shades of these colors. A spotted one of mine that has been a delight is Paphiopedilum Langley Pride ‘Burlingame’ HCC/AOS (see the color photographs in the center of this topic for an illustration).

Figure 12-19: A modern complex hybrid showing its full, round flower.

The whites have been particularly elusive in this quest for perfection. An older hybrid, Paphiopedilum F.C. Puddle (see Figure 12-20), doesn’t match many of today’s hybrids in terms of size and shape but is still in many collections today because it’s a charming dependable grower and bloomer.

A different kind of slipper orchid

All the slipper orchids that I cover up to this point in this topic are tropical ones found in the old-world tropics, mostly various parts of Asia. Another type of lady’s slipper has been known about since the 1800s but is now witnessing a strong new interest by orchid lovers. This group is called phragmipediums or simply “phrags.”

Phragmipediums call their home Central and South America. Many grow in the mountains, and number more than 30 species. They have a similar growth habit to some of the paphiopedilums and have the same requirements for humidity and temperatures.

Figure 12-20: Paphiopedilum F.C. Puddle is an older white hybrid still appreciated today.

Culturally, they have some differences. In general, they like it wetter than paphiopedilums. In fact, they’re commonly grown in platters of fresh water. This practice is unheard of with most other orchids! Also, they prefer more light — similar to cattleyas. These used to be expensive plants, but their prices have come down thanks, in part, to Hawaiian growers who have perfected their culture so they can now be grown to selling-size plants in record-breaking time.

Most of the flowers are twisted and dangling, are borne sequentially, and are found in shades and stripes of green and maroon. However, there are some key exceptions. Phragmipedium besseae is bright red-orange to yellow, Phragmipedium xerophyticum is white with a touch of pink, and Phragmipedium schlimii (see Figure 12-21 for a hybrid of this species) is a shade of pink as is Phragmipedium fischeri. But the absolute star of the show is a recently discovered marvel, Phragmipedium kovachii, with immense 7- to 8-inch (17.5-to 20-cm) magenta flowers. (See the nearby sidebar for more on this special plant.)

Although there has always been interest in the phragmipedium species, it is the hybrids that everyone its talking about. These newer hybrids are more vigorous and easy growing then most of the species and are becoming available in a broad range of colors. Many new ones are on the horizon but here are a few to look out for:

- Phragmipedium Andean Fire has attractive dark red 3/2-inch flowers on tall flowering stems.

- Phragmipedium Cardinale is a classic hybrid that reliably produces many pink flowers.

- Phragmipedium Hanne Popow has delightful small pink flowers and is an old favorite that is still offered and is frequently used as a parent to produce newer hybrids.

- Phragmipedium Jason Fischer has eye-popping brilliant, broad, flat red flowers.

- Phragmipedium Les Dirouilles displays huge, spectacular green, chestnut, and burgundy flowers with long, twisted petals.

- Phragmipedium Sorcerer’s Apprentice has broad foliage with very large and dramatic flowers with twisted petals in shades of green, brown, and burgundy.

Figure 12-21: Phragmipedium ‘Wilcox’ AM/AOS is a lovely hybrid with a delicate beauty.

New Phrag creates a scandal!

Phragmipedium kovachii was “discovered” in 2002 at a roadside vendor in northeast Peru by an American orchid enthusiast, J. Michael Kovach. He immediately recognized it as being exceptional and probably new to the orchid world. Kovach purchased this rare orchid and pirated it back to the United States, illegally, with grand visions of his name entering the annals of orchid history by having this “holy grail of orchids” named after him.

He rushed it to the orchid experts at Selby Botanical Garden, one of the world’s leaders in orchid research, to get it identified, documented, and officially described in Latin so it could be published in a botanical journal, thereby assuring that the orchid would be his namesake.

Now the fly in the ointment — the feds. They got word of Kovach’s “discovery” and orchids hit the fan. Kovach was indicted, and they threatened to fine Selby Botanical Gardens 8100,000 (it was plea-bargained to 85,000 and three years’ probation). Selby botanists, administrators, and board members’ heads rolled.

Even though it was part of the plea bargain that the name of this orchid be reverted to an earlier proposed name, Phragmipedium peruviana, most orchid people think it will most likely never happen.

And the scandal goes on. In the spring of 2004 at a Miami orchid show, a vendor and orchid grower from Peru, along with another orchid vendor and grower from Texas, were arrested for selling and smuggling endangered orchids including plants of Phragmipedium kovachii.