In This Topic

- Knowing how much light your orchid needs

- Providing enough humidity

- Giving your orchids a breath of fresh air

- Getting the temperature right

Orchids are not difficult to grow. But, like all plants, they have certain needs that have to be met so they can perform their best. In this topic, I detail orchids’ most fundamental requirements and the simplest, most effective ways to provide them, based on my 40 years of experience growing orchids on my windowsills, under lights, and in a greenhouse.

If you put a little effort into modifying your growing environment to help your orchids feel at home, it’ll pay off in healthy plants that provide plenty of flowers.

Let There Be Light!

Light is essential for all green plants, including orchids. Light, water, and carbon dioxide are the raw materials plants use to produce their food. Providing enough light is the most challenging requirement for indoor gardeners in areas of the country like the Northeast and the Midwest, who experience short days and low light during the winter. Fortunately, plenty of species and hybrids of orchids don’t require super-high light intensities and so are more suited to these climates.

If you’re blessed with naturally high light — like the kind found in Hawaii, California, and Florida — you can grow both the high- and the low-light-intensity orchids. You just have to use greenhouse shading or light-reducing draperies to satisfy those orchids requiring modest amounts of light.

The ins and outs of light

Orchids are traditionally categorized by their light requirements — high, medium, and low.Most orchids are in the medium light category. You can easily grow orchids in the low to medium light categories under artificial lights or on bright windowsills. From a practical point of view, the orchids with high light requirements are most successfully grown in bright greenhouses.

Greenhouses: Your high light source

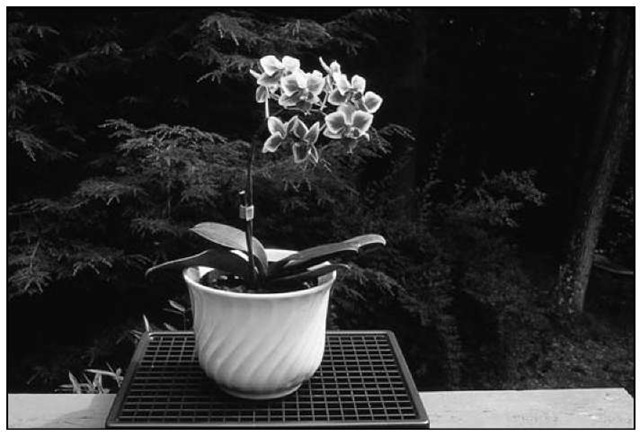

Greenhouses, like the one shown in Figure 5-1, are the most efficient collectors of natural light.

The amount of light penetrating the greenhouse is determined by the glazing material used, its geographic location, how it’s sited on the land, and whether it’s shaded by surrounding trees or a commercial shading compound or fabric.

The greenhouse option is the most expensive, but you don’t have to own one to grow most of the orchids in this topic.

Figure 5-1: High-quality greenhouse setups provide shading and efficient use of space to accommodate as many orchids as possible.

WindoWsills: Not all WindoWsills are created equal

Windowsills are the most readily available and cost-effective source of light. The amount of light windowsill growing can provide is primarily determined by The size of the windows.

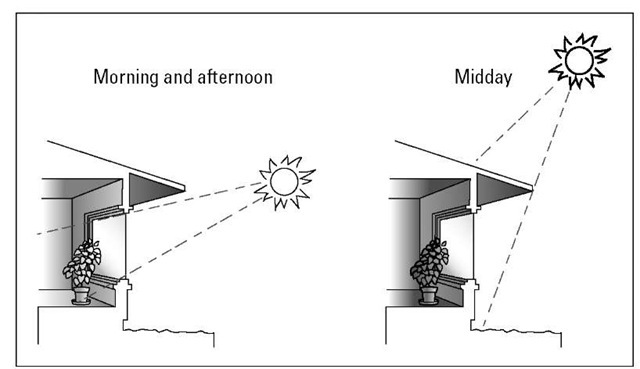

Whether there is an overhanging roof: This can make a difference in how much light will actually reach the plants (see Figure 5-2).

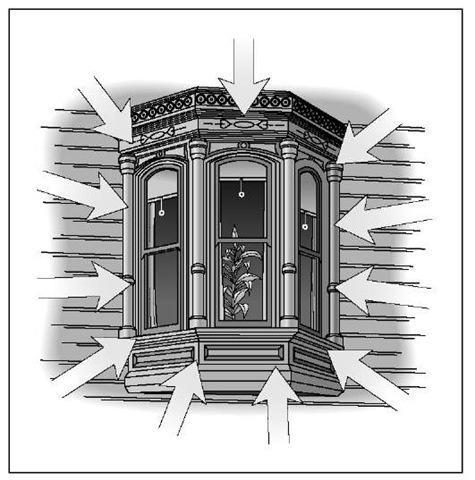

How far back the windows are recessed: Bay or bow windows expose the plants to more light than other types of windows (see Figure 5-3).

The direction the windows face: Whether the windows face north, south, east, or west makes a big difference in the amount and quality of light the orchids will receive:

• South-facing window: This is the brightest window, so it offers the most possibilities. It’s an ideal location for those orchids that demand the strongest light. You can place most of the other less-light-demanding orchids a few feet back from the window, or you can diffuse the light from the window with a sheer curtain. Note: This exposure can get hot, especially during the summer.

Figure 5-2: The extent of the roof overhang will make a difference in the amount of light the orchids will receive.

• East-facing window: This window offers morning sunlight, which is bright but not too hot. During the spring, summer, and fall, this is usually an ideal exposure for most orchids in this topic, except those that require extremely high light (like vandas). During the short, dark days of winter, many of these same orchids usually prefer a south-facing window.

• West-facing window: This window receives as much light as the east window but, because it gets afternoon light, it’s much hotter — so this isn’t as desirable a location as the east-facing window. If you need to use a west-facing window, make sure your orchids don’t dry out too much because of this increased heat.

• North-facing window: A north-facing window simply doesn’t provide enough light to sustain the healthy growth of orchids. Use it for low-light plants like ferns.

How far the plants are placed from the windows.

The age and condition of the glass: Tinted and reflective glass can dramatically reduce light intensity, so it’s usually not recommended. No matter what kind of glass you have, keep your windows clean, especially during the winter when the light intensity is low, so your orchids will receive as much light as possible.

The time of the year: During the winter, the sun is lower in the sky and the day length is shorter. The opposite is true during the summer. As a result, a south-facing window may be fine for certain orchids during the winter, but you may have to move the orchids to an east-facing window during the summer.

Listening to your orchids

Different types of orchids have varying light requirements because they naturally grow in a wide range of habitats. Some thrive in full sun on exposed rocks, while others are at home in dense jungle shade.

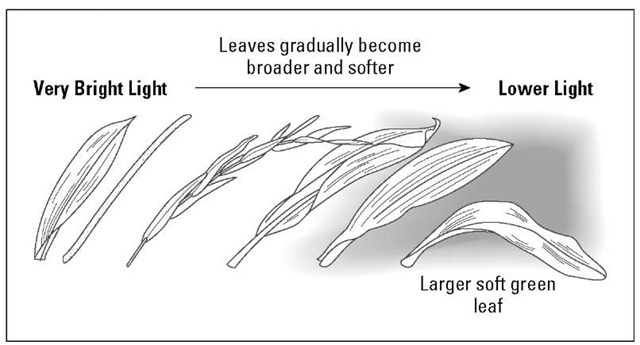

The leaves of the plant give you some clue as to their light requirements (see Figure 5-4). Those with very tough, thick, stout, and sometimes narrow leaves frequently are adapted to very high light intensity. When the leaves are softer, more succulent, and wider, this is usually a clue that they’re from a lower-light environment.

Figure 5-3: Bay windows increase the size of the growing area and the amount of light the plant receives, because light can penetrate from multiple angles.

Figure 5-4: The type of leaf indicates an orchid’s light requirements.

Your orchids will tell you by their growth habits and leaf color if they’re getting adequate, too little, or too much light. When orchids are getting enough light, you’ll notice the following:

The mature leaves are usually a medium to light green.

The new leaves are the same size or larger and the same shape as the mature ones.

The foliage is stiff and compact, not floppy.

The plants are flowering at approximately the same time they did the year before.

One of the most frequent results of inadequate light is soft, dark green foliage with no flowering. Another symptom of inadequate light is stretching, where the distance between the new leaves on the stem of orchids like paphiopedilum, phalaenopsis, or vandas is greater than with the older, mature leaves. On other types of orchids, the new leaves tend to be longer and thinner.

When orchids get too much light, their leaves turn a yellow-green color or take on a reddish cast and may appear stunted. In extreme cases, the leaves show circular or oval sunburn spots (see Figure 5-5). The sunburn is actually caused by the leaf overheating. Although, in itself, this leaf damage may not cause extreme harm to the plant if the damage is isolated to a small area, it does make the plant unsightly.

If the sunburn occurs at the growing point, it can kill that leaf or the entire plant. Higher light intensities than are usually recommended are possible with some orchids if you increase the ventilation to lower these elevated leaf temperatures. Some orchid cut-flower growers like to push their orchids with the highest light intensity they can take without burning to yield the maximum amount of blooms. However, for most hobby growers, I don’t recommend this.

Figure 5-5: A paphiopedilum leaf with a round or oval brown spot caused by too much light or sunburn.

No natural light? No problem!

Artificial light sources make it possible for everyone without greenhouses or bright windowsills to enjoy growing orchids in their homes. Although the limitations of what can be grown under these light sources are only restricted by equipment and electricity costs, it’s a very practical method of growing for low- to medium-light orchids.

Wading through the many lighting options available today can be a daunting task, especially for beginners. In this section, I help you out.

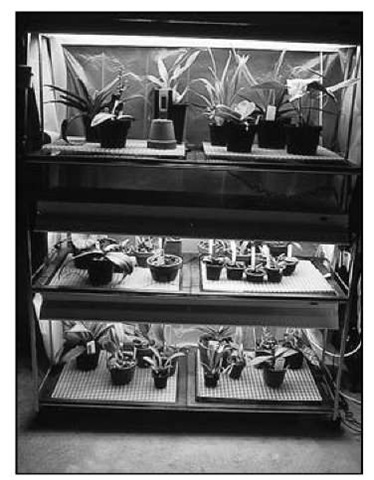

Fluorescent lights

Fluorescent systems are still the most accessible and economical lighting systems to buy. Three-tiered light carts, like the one shown in Figure 5-6, are highly versatile and practical. Most of them are about 2 feet wide by 4 feet long, so their three shelves provide 24 square feet of growing area. If you grow compact orchids, this will be enough space to have at least one or more orchids in bloom year-round. If you collect miniatures, it will provide a growing space adequate for an entire collection. The convenience of such a cart can’t be beat. You can place it in a heated garage, in a basement, or in a spare bedroom.

When the orchids start to produce their tall orchid spikes, there usually isn’t enough head room under most fixed-height light units to accommodate this growing spike. At that point, you can move the orchids to a windowsill or use a light fixture that can be raised as the flower spikes develop, like the one shown in Figure 5-7.

Which bulbs or lamps you should burn in your fixtures is a highly debated topic. Years ago, the only real choice was cool white and warm white tubes. Some people still feel that a 50/50 mix of these tubes is the best option, because they’re bright and very inexpensive.

Over 40 years ago, Sylvania started manufacturing Gro-Lux tubes — designed to provide light that more closely reflected the spectrum of light that plants used in photosynthesis, the process that plants use to produce their own food. This started a new race to produce the “best” plant bulb. The evolution of lamps has gone from the Gro-Lux to wide-spectrum bulbs and now to full-spectrum bulbs. The light cast by the full-spectrum lamp is supposed to most closely resemble natural sunlight. Viewed under these lamps, colors of the flowers are rendered more accurately.

Figure 5-6: Four-tube, rather than two-tube, units are highly recommended for low- to medium-light orchids.

Figure 5-7: An adjustable light fixture like this one is very handy for accommodating developing flower spikes.

I’ve grown orchids well under all these types of lamps. If you want to have the flowers appear most naturally colored under the lights and don’t mind paying a premium for the lamps, the full-spectrum types are the best choice. The most economical pick — and still satisfactory — is the 50/50 ratio of warm-white to cool-white lamps. A compromise would be a blend of half warm-white and cool-white tubes and half wide- or full-spectrum lamps.

High-intensity-discharge lights

Newer to the artificial-light choices are high-intensity-discharge lights. These are very efficient in their production of light and are especially useful where you want to grow orchids requiring higher light intensities than fluorescent lamps can provide and/or where you want a greater working distance between the lights and plants (see Figure 5-8).

High-intensity-discharge lights do have the disadvantage of producing quite a bit of heat, so make sure not to get the plants too close to the bulbs.

Figure 5-8: Approximate growing areas for different wattages of high-intensity-discharge lamps.

The two most frequently used lamps for these systems are metal halide (MH) and high-pressure sodium (HPS). HPS is more energy-efficient than MH, but the light it emits is orange-yellow and distorts the color of the flowers and foliage. MH produces blue light that is more pleasing to the eye. Some manufacturers now produce lamps that combine the advantages of both.

Another newer option is the high-intensity compact fluorescent light. The fixtures for these look much like high-intensity-discharge (HID) units. They don’t produce quite as much light as HID, but they have the advantage of producing little heat — so there is much less likelihood of orchids being burned.

If you’re a beginner light gardener, I recommend starting with fluorescent-light setups. I find them to be most practical. Later, if you have the need, you can give the high-intensity-discharge lamps a try.

Humidity: Orchids’ Favorite Condition

Humidity is something you can’t see, but you can feel it on a muggy summer day or in a steamy greenhouse. The vast majority of orchids are from the tropics, where high rainfall and humidity prevail. When orchids get enough humidity, they grow lushly and their leaves have a healthy shine.

Insufficient humidity can stunt an orchid’s growth and, in severe cases, it can cause brown tips on leaves. It can also contribute to buds falling off (known as bud blast), leaves wrinkling, and drying of the sheaths (the tubelike structures that surround the developing flower buds), which can result in twisted or malformed flowers.

During the winter, homes, especially those in cold climates with forced-air heating systems, usually have a relative humidity of about 15 percent. Because this is the average humidity found in most desert areas, you have to do something to raise the humidity to at least 50 percent — a level that will make orchids happy.

For greenhouses, this process is a relatively simple matter. You can either regularly hose down the walkways or hook up foggers and commercial humidifiers to a humidistat so that the entire operation is automatic.

If you’re growing your orchids in your home, you’ll need a different approach. High humidity levels that would be no problem in a greenhouse will peel the paint, plaster, and wallpaper off the walls of your house. Assuming that’s not the look you’re going for, you can take several steps to get to the desirable humidity range without causing damage to your house.

If you can, put your orchids in a naturally damp area, like the basement.

Wherever you put your orchids, use a room humidifier. I find the best type of humidifier is an evaporative-pad humidifier (in which fans blow across a moisture-laden pad that sits in a reservoir of water). An evaporative-pad humidifier is usually better than a mist humidifier, because, unlike a mist humidifier, it doesn’t leave your orchids with a white film (from the minerals in the water being deposited on the leaves).

To further increase the humidity level, you can try growing the plants on top of a waterproof tray filled with pebbles. Add water to the tray so that the level is just below the surface of the pebbles, then put the plants on top of this bed of damp gravel. The problem that I find with this system is that the pots, especially the heavy clay ones, frequently sink into the pebbles, resulting in the media in the pots getting soggy and, after repeated waterings, the pebbles becoming clogged with algae and being a repository for insects and various disease organisms.

The approach that I think works much better is to add sections of egg-crate louvers (sold in home-supply stores for diffusing fluorescent lights) to the trays (see Figure 5-9). You can cut this material with a hacksaw to whatever size you need. It’s rigid so it will support the plants above the water, and the water is more exposed to air, so more humidity results. The grating is simple to clean — just remove and spray it with warm water. To prevent algae or disease buildup, you can add a disinfectant like Physan to the water in the trays.

Misting is another way to increase humidity. This works okay, but in order for it to be effective, you need to do it several times a day, because the water usually evaporates very quickly. A problem with misting is that, if your water source is mineral-laden, your orchid’s leaves may become encrusted in white — not only is this unsightly, but it keeps light from penetrating to the leaves. A benefit to misting is that it can clean the dust from the leaves.

Figure 5-9: An egg-crate louver set inside a waterproof tray. This setup is a simple way to increase humidity, and it’s easy to keep clean.

Blasted bud blast!

Nothing is more disheartening than having the buds of your orchids shrivel up right before they open! This is referred to as bud blast and is caused when the orchid undergoes different types of stress. Here are some of the specific causes of this exasperating event:

Low humidity

Hot air from furnaces or cool, dry air form air-conditioners directly blowing on the orchid plant

- Over- or underwatering

- Poor root development

- Temperatures that are too high or too low

- Water standing in the buds or bud sheaths

- Dramatic change in the orchids’ environment, like bringing the plants from outside to inside

- Natural-gas leaks in the house

- Ethylene gas from ripened fruit

- Light that’s too bright on the developing flower buds

- Pollution, such as smog

Fresh Air, Please!

In most tropical lands where orchids reside, they luxuriate in incessant, but gentle, trade winds. Air movement in a growing environment ensures a more uniform air temperature and dramatically reduces disease problems by preventing the leaves from staying wet too long. It also evenly distributes the gas (carbon dioxide) that is produced by the plants in the dark and used by the plants to produce their food during the daylight hours.

You don’t want to create gale-force winds in your growing area, but you do want to produce enough airflow to cause the leaves of the orchids to very lightly sway in the breeze. I’ve found that two of the most effective methods for providing such an airflow in both a hobby greenhouse and an indoor growing area are ceiling fans and oscillating fans.

Ceiling fans

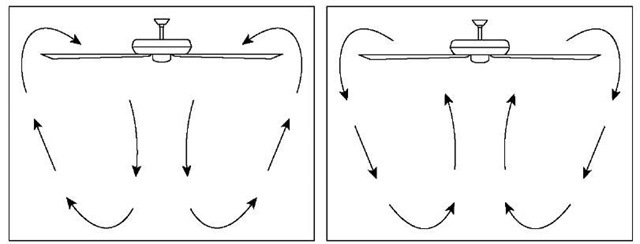

Ceiling fans move a huge volume of air at a low velocity in a circular pattern, so they effectively prevent severe temperature differences, are inexpensive to operate (they use about the same electricity as a 100-watt bulb), are quiet, have variable speeds, and are easy to install. They stand up well to moist conditions, especially if you buy the outdoor types. Another nice feature is that you can adjust the air-circulation pattern on most of them so that they can either push warm air down (the recommended winter setting) or pull cool air up (usually the best summer setting), as shown in Figure 5-10.

Oscillating fans

Oscillating fans are also a good choice, because they effectively cover large areas with a constantly changing airflow pattern without excessively drying off the plants.

Figure 5-10: Ceiling fans can be set either to push warm air down (best for winter) or pull cool air up (best for summer).

If you decide to go with oscillating fans, splurge for the better-grade ones. Fans that are very inexpensive have plastic gears that strip easily, so the oscillating feature won’t last long.

Muffin fans

You may have small hot or cold spots in your greenhouse, win-dowsill, or light cart where just a touch of airflow is needed. This is where small muffin fans, frequently sold for cooling computers (available at electronics or computer-supply stores), are perfect for the job. They’re efficient, quiet, and very inexpensive to operate.

Some Like It Hot, Some Like It Cold: Orchid Temperature Requirements

Orchids are frequently placed by professional orchid growers into three different categories based on their night temperature preferences:

Cool: 45°F to 55°F (7.2°C to 12.8°C) Intermediate: 55°F to 60°F (12.8°C to 15.6°C) Warm: 65°F (18.3°C) or higher

The assumption is that the daytime temperature will be at least 15°F (9.5°C) warmer than these night temperatures.

These numbers are guidelines, not absolutes. Most orchids are quite adaptable and tolerant of varying temperatures, short of freezing. But for optimum growth, these temperature ranges are good targets.

Get rid of the laggards!

You may find that a few of your orchids just don’t appreciate the home you’ve given them. Maybe they don’t get enough light or your home is too cool. Whatever the reason, if you’ve done your best to provide the right conditions and the orchid still doesn’t grow well and bloom, it’s time to get tough and get rid of it! Give it to a friend with different growing conditions. There are too many orchids out there that are easy to grow to be wasting your time and valuable and limited growing space on a poor performer.

Too-low temperatures

If orchids are exposed to cooler than the recommended ranges, their growth will be slowed down and, in extreme cases, buds may fall off before they open (known as bud blast). Also, cooler temperatures can reduce the plant’s disease resistance.

Too-high temperatures

If it gets too hot, orchids will show their displeasure by slowing or stopping their growth, having their flower buds wilt before they open, having their leaves and stems shrivel, and in extreme cases, by dying. A short bout of higher-than-desired temperatures won’t be that harmful as long as the humidity stays high.

One critically important factor with orchids is that they need at least 15°F higher daytime temperatures than they get in the evening. If they don’t get this temperature difference, the orchids won’t grow vigorously and, probably most importantly, they won’t set flower buds. Not meeting this temperature requirement is one of the most common reasons that homegrown orchids don’t bloom.

Giving Your Orchids a Summer Vacation

Some orchid growers continue growing their plants indoors under lights, on windowsills, or in their greenhouses throughout the summer. The challenge during this time is to reduce the light intensity and control the high heat, both of which can be damaging.

For these reasons, summering the orchids outdoors is an attractive option. For the light gardener, this means a welcome relief from high electric bills; and for the greenhouse and windowsill grower, it provides an opportunity to clean up the growing area. Also, most orchids aren’t in bloom during the summer, so they aren’t at their best visually and they respond very favorably to a summer vacation outdoors.

Besides providing an opportunity to clean up your indoor growing area, having a space outdoors allows you to apply pest controls, if necessary, without smelling up your house. The natural temperature differential between day and night, especially in the early fall, is very effective in setting flower buds for the upcoming late-fall and winter blooming.

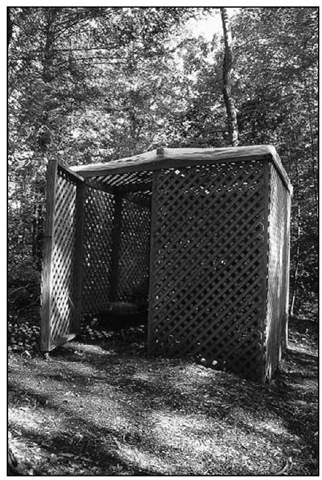

A shade house

I summer my orchids in a shade house made of preconstructed lath (slates of crisscrossed wood), nailed or screwed to pressure-treated upright wood supports. Figures 5-11 and 5-12 show what my shade house looks like.

Shading (usually about 50 to 60 percent or more depending on the location of the shade house and the types of orchids grown) is necessary and is provided by lath or shading fabrics. I also installed in this shade house a watering system made up of multiple small sprayers or misters controlled by a timer that has a manual override. I grow the plants on stepped wire frame benches that ensure even lighting and easy watering.

Figure 5-11: My shade house is an 8-foot (2.4-m) square simply constructed using wood lath and 4-x-4-inch (10-x-10-cm) pressure-treated wood posts.

I cover the roof of the shade house with 6 mil (0.006-mm-thick) heavy-duty clear plastic, which is stretched over a peaked wooden frame. I used to leave the roof of the lath house open to receive natural rainfall, but I found that it sometimes rained when I didn’t want it to (at night, when it was too cool, or when it was already wet). I find the covered roof gives me the control to water when my plants need it.

Figure 5-12: Inside the shade house, plants are arranged on stepped-wire benches to allow easy watering and good air and water drainage.

A portable greenhouse

I’ve also summered orchids in a portable greenhouse on the deck (see Figure 5-13). If you use such a structure, be sure to put it in a place that receives shade during the heat of the day, or use a commercial shading fabric to cut down the light intensity. Also, be mindful of the daytime temperatures inside such a structure. These units require good systems of ventilation; otherwise, temperatures inside them can skyrocket in sunny periods.

Keeping things in balance: The yin and the yang of orchid growing

When it comes to your orchids’ growing conditions, it’s a matter of keeping everything in balance. Here are some tips to keep in mind:

- If the air temperature is cool, the orchids need less water and light.

- If the humidity is high, the orchids need more air circulation.

- If the light is very bright and/or the temperature is high, the humidity needs to be high.

When orchids are not actively growing, reduce or stop fertilizing.

If the temperatures are high, the light and humidity need to also be high and the orchids will require more-frequent watering.

Figure 5-13: An outdoor portable greenhouse can be an ideal place to put your orchids in the summer.

Some orchids enjoy hanging out

Orchids that have higher light requirements, like vandas and asco-cendas, grow wonderfully dangling from pot hangers clipped to the pot (see Figure 5-14) and then hung from a pole or other support. Just make sure the light intensity of this growing area matches the needs of the orchids.

Figure 5-14: You can easily summer your orchids outdoors by using pot clamps to hang them from a freestanding support or a suspended rod against the garage.