Difficult Breathing (Dyspnea)

When a person is making a distinct effort to obtain oxygen and get rid of carbon dioxide, breathing becomes difficult. The term for difficult or painful breathing is dyspnea. This condition may be temporary, such as when a runner breathes in gasps at the end of a race, or when a person runs upstairs and pants to get his or her breath when reaching the top. Obesity also can cause dyspnea, especially on exertion. In some cases, breathing difficulty is more or less constant, as in the acute stages of pneumonia or emphysema or in some types of heart disease. When the difficulty is so marked that the client can breathe only when in an upright position, it is called orthopnea.

Obstructions of the air passages by secretions or foreign objects interfere with breathing. Asthma is a condition that causes difficult breathing because of spasms and edema of the bronchi.

Normally, the proportion of respirations to heartbeats is 1:5 in adults. Respirations usually increase if pulse rate increases, but not always in definite proportion. Usually, pulse rate increases faster than respiration rate. However, respiration rate increases faster than pulse rate in respiratory diseases.

Characteristic signs of breathing difficulty are heaving of the chest and abdomen, a distressed expression, and cyanosis (bluish tinge) in the skin, especially in the lips (circumoral cyanosis) and mucous membranes of the mouth. In severe conditions, cyanosis spreads to the nails and extremities and eventually becomes apparent over the client’s entire body. An excess of carbon dioxide causes the bluish tinge. Cyanosis also may result from a circulatory or blood disorder. It is easier to detect in light-skinned people; the condition appears as a dusky gray color in dark-skinned individuals.

Cheyne-Stokes respirations are slow and shallow at first, gradually growing faster and deeper, then tapering off until they stop entirely. Periods of apnea may last for several seconds and then the cycle is repeated. When observing a client with these respirations, document the length of the apnea period in seconds. Usually, the client experiencing Cheyne-Stokes respirations is not cyanotic. Cheyne-Stokes respirations are serious and usually precede death in cerebral hemorrhage, uremia, or heart disease.

Counting Respirations

Respirations are the easiest vital signs to determine. Each time such determinations are made, check them against the baseline information (see In Practice: Nursing Procedure 46-4).

Key Concept Remember to inquire about pain when measuring vital signs.

ASSESSING BLOOD PRESSURE

Assessing blood pressure (BP) is especially important for clients with abnormally high or low readings, for postoperative clients, and for clients who have sustained serious injury or shock. The BP reading gives significant information about the client’s status and is one of the most important parts of nursing assessment. In routine client care, BP is usually assessed at least twice daily.

NCLEX Alert Taking and recording of VS is used to help demonstrate the course of a clients conditions. As you read the scenarios in the NCLEX examination it will be important for you to show your knowledge and understanding of correct technique in obtaining VS.

Regulation of Blood Pressure

As the heart forces blood through the arteries, the blood exerts pressure on the arterial walls. Blood pressure is determined by two major factors: cardiac output and peripheral resistance.

Cardiac output is a combination of the heart rate and the amount of blood pumped out of the heart with each contraction (stroke volume). These are measured over 1 minute.

Peripheral resistance is the resistance of blood vessels to the flow of blood. Peripheral resistance affects both blood pressure and the work required of the heart to pump the blood. When peripheral resistance is increased, the heart must pump harder to push blood through the blood vessels. Factors increasing peripheral resistance include a loss of elasticity in the walls of the vessels (arteriosclerosis, “hardening of the arteries”), a buildup of plaque (atherosclerosis), or a combination of the two. The “hardened” arteries and plaque increased resistance to blood flow. The heart must work harder, and blood pressure is higher.

Peripheral resistance can be lowered when the walls of the blood vessels become stretched (distended). If peripheral resistance is low, the heart does not have to pump as hard, and blood pressure lowers. However, the vessel walls must have a certain amount of elasticity in order for blood to circulate.

The amount of blood in the circulatory system also influences blood pressure. If the total amount of circulating blood decreases, the amount of blood available for the heart to pump out with each contraction decreases and blood pressure decreases. On the other hand, if the circulating volume is too high, the stroke volume increases, and blood pressure increases. High BP is called hypertension (HTN); low BP is called hypotension.

Key Concept If heart rate, stroke volume, circulatory volume, or peripheral resistance increases, blood pressure increases. If there is a decrease in heart rate, stroke volume, circulatory volume, or peripheral resistance, blood pressure decreases.

Systole and Diastole

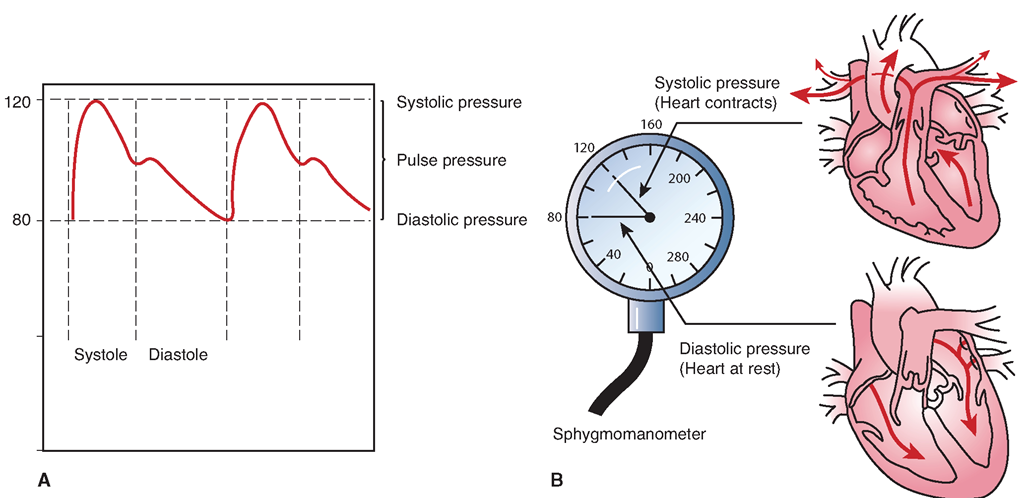

The blood pressure is at its highest with each heartbeat during heart contraction or systole; this measure is the systolic blood pressure (SBP). Pressure diminishes as the heart relaxes. Pressure is lowest when the heart relaxes before it begins to contract again (diastole); this measure is the diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (Fig. 46-14). The difference between the systolic and diastolic readings is called the pulse pressure. If the pulse pressure is too narrow, this indicates that the arteries are not properly relaxing between heartbeats, due to a condition such as arteriosclerosis. If the pulse pressure is too wide, the vessels may not have enough elasticity or tension to sustain adequate blood flow.

FIGURE 46-14 · (A) Blood pressure measurement identifies the amount of pressure in the arteries when the ventricles of the heart contract (systole) and when they relax (diastole). (B) The pressure of blood in the arteries is higher during systole (SBP) and is lower during diastole (DBP).

A value called the mean arterial pressure (MAP) is calculated using a mathematical formula. Note that this formula yields an approximate value.

or

Mean arterial pressure is approximately the value of the diastolic pressure plus one-third of the pulse pressure. It denotes the average pressure within the arteries. An electronic device is used to determine the exact average pressure or MAP (see Fig. 46-15).

Normal Blood Pressure

Normally, the difference between the systolic pressure and the diastolic pressure (pulse pressure) is a number equal to one-third to one-half of the systolic pressure. Both readings give information; a very wide or very narrow difference between the two indicates a problem. Average systolic pressure for an adult aged 20 is approximately 115 to 120, and average diastolic pressure is approximately 75 to 80. In the person with a BP of 120/80, the pulse pressure is 40, or one-half (1/2) the systolic. Some people have a naturally low BP; if it is around 100/60, this is considered normal.

Blood pressure may increase gradually with age, although this is not considered desirable. Any increase results from aging of the heart and arteries. Any pressure much higher than the recommended values (hypertension) is a sign of a circulatory problem. A very low BP (hypotension) may indicate hemorrhage or shock. A systolic reading of 60 or less usually indicates serious difficulty. A diastolic reading greater than 90 is usually considered dangerously high. Medications can cause variations and antihypertensive medications can be given to lower blood pressure. The normal blood pressure in a child, as with other vital signs, varies with age. Table 46-4 identifies current recommendations regarding normal blood pressure parameters.

Methods and Equipment

The BP can be measured directly by means of a probe or catheter inserted into the client’s artery (arterial line). The tip of the catheter has special sensors that measure pressures and transmit this information electronically. The systolic and diastolic pressures are displayed in the form of a wave. This is called direct measurement of BP. Many critical care units use this type of measurement because constant monitoring is essential (Fig. 46-15).

TABLE 46-4. Recommendations for Normal Blood Pressure Parameters*

|

AGE (YEARS) |

SYSTOLIC (mm Hg) |

DIASTOLIC (mm Hg) |

|

Newborn |

80 |

46 |

|

10 |

103 |

70 |

|

20 |

120 |

80 |

|

40 |

126 |

84 |

|

60 |

135 |

89 |

|

The American Heart Association (AHA) identifies the following categories in persons not receiving antihypertensive medications: |

||

|

Normal |

<120 |

<80 |

|

High normal (prehypertension) |

120-139 |

80-89 |

|

Stage I HTN |

140-159 |

90-99 |

|

Stage II HTN |

160+ |

100+ |

|

The AHA states that the risk of heart disease and stroke increases at the following rates: |

||

|

115/175 |

normal |

|

|

135/85 |

X 2 |

|

|

155/95 |

X 4 |

|

|

175/105 |

X8 |

|

*Note: These recommended classifications vary among references. HTN, hypertension.

FIGURE 46-15 · An automated vital signs monitor is often seen in intensive care units (ICUs), coronary care units (CCUs), and emergency departments (EDs). This machine not only shows a continuous readout of arterial blood pressure (120/70), pulse or heart rate (HR 60), and electrocardiogram (ECG), it can print an ECG strip at the push of a button. In addition, this particular monitor indicates more sophisticated measurements, such as mean arterial pressure (91), central venous pressure (9), venous blood pressure (30/17), and mean venous pressure (23), as well as other pertinent values.

Automated BP and VS monitoring can also be accomplished indirectly, using a traditional blood pressure cuff and a less-sophisticated electronic machine. In this case, the cuff inflates and deflates automatically and the values are digitally displayed on the screen. Many of these machines can be set to keep a record of the readings. If the automatic machine is set to measure indirect blood pressure, fewer values are obtained.