POSTOPERATIVE NURSING CARE

The Postanesthesia Care Unit

Nearly all hospitals have a room or suite set aside for the care of clients immediately after surgery. Various names are used to identify this area, including postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and the postanesthesia recovery (PAR) area. The LPN/LVN requires additional education in order to work in the OR or PACU.

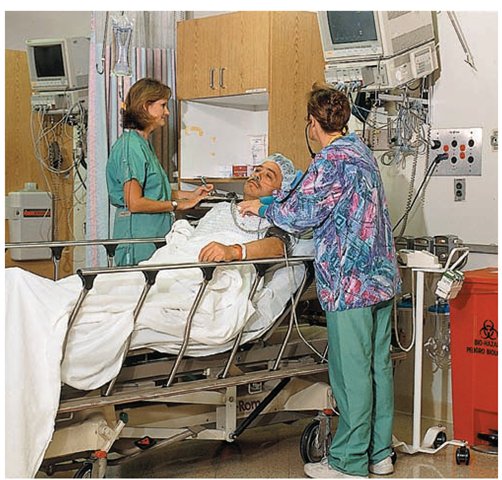

The client is carefully monitored in the PACU until he or she is recovered from anesthesia and is medically cleared to leave the unit. Specific monitoring includes the basic ABCs of life, airway, breathing, and circulation.A complete systems assessment of the client is performed immediately on arrival in the PACU; measures are taken in an attempt to prevent postoperative complications. It is important to identify clients who are particularly at risk. Because the PACU is located next to the OR, surgeons and nurses, as well as specialized equipment, are readily available in case of emergency (Fig. 566). Concentrating postoperative clients in a limited area makes it possible for nurses to observe immediate postoperative clients closely.

Articles that may be needed for care are located near the client’s unit in the PACU:

• Breathing aids: Oxygen, suction equipment, nasal and oral airways, pulse oximeter, mechanical breathing bag or other resuscitation equipment, and emergency equipment such as a laryngoscope, otoscope, ophthalmoscope, tracheostomy set, or endotracheal tube

• Circulatory aids and related medications: BP and pulse monitor, stethoscope, IV solution and pumps, tourniquets, syringes and needles, cardiac monitor, cardiac arrest equipment, cardiac drugs, medications to counteract narcotic overdose, respiratory stimulants, the defibrillator and a backboard for CPR

• Drugs: Narcotics, sedatives, and drugs for emergency situations

• Other supplies: Surgical dressings, sandbags, warmed blankets, extra pillows, and various other items. A crash cart is also available. Special equipment for a particular client, such as a traction setup or back brace, is also present.

FIGURE 56-6 · The PACU contains special equipment, to deal with any postoperative emergency.

Each client unit has a recovery bed/cart equipped with side rails, poles for IV medications, wheel brakes, and a computer. The cart can be moved easily and adjusted to elevate or lower the head or feet. The bedside stand holds supplies and equipment such as a bedpan and/or urinal, tissues, an emesis basin, tongue blades, a face cloth, and a towel. Each unit has outlets for piped-in oxygen, suction, and BP and other monitoring equipment. Warmed bath blankets are available to assist the client with the normal body chilling that usually follows anesthesia.

Key Concept In the case of ambulatory day surgery clients may recover in a special reclining lounge chair (Fig. 56-7). They still require careful nursing observation, and client and family teaching are a vital part of care before discharge.

FIGURE 56-7 · In ambulatory surgery, the client may be placed in a lounge chair for recovery from anesthesia.

Moving the Client to the PACU

When a client is moved from the operating room to the PACU, every effort is made to avoid unnecessary strain or injury to the client and to accomplish the transfer as quickly as possible with the least exposure. Enough people must be available for the safe transfer of the semiconscious client from the OR table to the PACU cart. The anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist and circulating nurse go to the PACU with the client to make certain the client’s condition is stable. Having been responsible for monitoring the client’s condition throughout the surgical procedure until that responsibility transfers to PACU nurses, the anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist reports the client’s condition to the PACU nurse and leaves the surgeon’s postoperative orders and any required special instructions. The client then remains in the PACU until he or she is stabilized.

Key Concept All preoperative orders are null and void when the client enters the OR.Totally new orders must be written.

Some total procedures may be performed in the PACU. This includes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for clients in the mental health unit. These clients do not enter the OR itself, but receive the treatment and recover in the PACU.

Receiving the Client in the Nursing Unit

When the client is nearly awake, the PACU staff confers with anesthesia personnel to determine if the client is stable enough for transfer to the receiving unit. The stabilized client can then be transferred to the ambulatory recovery area or to a bed in the hospital. The PACU staff calls the receiving area before the client’s discharge from the PACU to report on the client’s condition, indicating what special equipment will be needed for the client when he or she arrives. The receiving nursing staff must have time to prepare for the client’s arrival.

Preparation of a room for a surgical client includes opening the bed by pulling all the top linens to the foot or side of the bed (see Fig. 49-1C). The linens are all clean. The bed is placed in its highest position; the head of the bed is flat. The furniture is arranged so the client can be easily transferred from the recovery room cart to the bed. Items are removed from the bedside stand, so they will not be in the way. All necessary equipment must also be in place before the client arrives. This includes equipment for vital signs, an IV pole, emesis basin, bed protector pad, suction equipment, oxygen, and other items specific to that client.

When the client arrives from the PACU, immediately check his or her vital signs and compare them with those obtained by PACU staff. Remember to include pain as the fifth vital sign.Any significant variation in vital signs must be reported immediately. Remember, the most important basic human need on Maslow’s hierarchy is that of obtaining oxygen. The airway must remain patent (open). The client’s neurologic status is also monitored. If the client has had local, spinal, or regional anesthesia, the sensory and motor functions must be monitored as well.

Key Concept The client’s blood pressure and respiratory effort are often lowered initially as a result of anesthesia. Pulse is often elevated, owing to administration of anticholinergic medications, such as atropine. Vital signs (VS) should stabilize before the client leaves the PACU. Remember that the client’s VS may have been elevated before surgery as a result of apprehension. It is important to know the baseline VS for each client.

A condition known as malignant hyperthermia (elevated body temperature) is not common, but may occur It usually begins in the OR and is the result of overcontraction of skeletal muscles. It has a genetic base, but may be triggered by anesthetics. Specific recognition and treatment are beyond the scope of this topic, but if the client’s temperature is elevated, report it immediately

The PACU nurse will provide an additional report to the floor staff. In Practice: Nursing Procedure 56-1 reviews information needed for receiving the client from the PACU.

When the client is settled in bed, and after initial vital signs have been taken and all immediate orders have been carried out, notify the client’s family that the client is back in the room. The family can reassure the client by their presence, although they should allow the client to sleep.

Nursing Alert Leave no client alone until he or she has fully regained consciousness. Check the physician’s orders and carry them out immediately

Immediate Postoperative Complications

It is the nurse’s responsibility to measure frequent vital signs after surgery. Observe the client postoperatively for immediate complications, including hemorrhage, shock, hypoxia (inadequate oxygen), and hypothermia (below normal body temperature).

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage (escape of blood from torn blood vessels) during or after surgery can lead to shock, requiring blood transfusions or other fluid replacement. Usually, the client’s blood has been routinely typed and cross-matched before surgery so compatible blood is available. Prompt action is necessary in the event of hemorrhage, because excessive bleeding could be fatal.

Secondary hemorrhage sometimes occurs postoperatively; consequently, inspect the client’s wound dressings frequently. If bleeding is noted, report it. Be sure to look under the client, because blood may pool there. However, concealed bleeding, also called occult or internal bleeding, is revealed mainly through signs of shock.

Key Concept If hemorrhage is internal, the client may need to return to the operating room for repair of blood vessels. This is a very dangerous situation.

BOX 56-4.

Signs of Shock

• Hypotension

• Narrowed pulse pressure

• Tachycardia; thready pulse

• Restlessness and anxiety

• Difficulty breathing

• Cyanosis or dusky skin color

• Extreme thirst

• Cold, clammy skin

• Hypothermia

• Low oxygen saturation (as measured by pulse oximeter)

• Slowed capillary refill

• Ringing in the ears; difficulty seeing

Hypotension and Shock

The blood pressure may be low (a condition known as hypotension) following surgery. This may be caused by blood loss, but may also be caused by withholding of food, fluids, and medications before surgery. Anesthetics and pain killers used may also cause hypotension. Many times, hypotension can be alleviated by the anesthesia personnel in the OR.

Hypotension should be reported immediately, as it can indicate shock. The most dangerous type of postoperative shock is known as circulatory or hypovolemic (low blood volume) shock, caused by severe hemorrhage.Severe blood loss is life threatening; cells cannot live without the oxygen carried by the blood. Be on constant alert for the signs of shock listed in Box 56-4.

Nursing Alert If shock occurs, take these steps:

• Call for help first.

• Control hemorrhage, using direct pressure if needed.

• Position the client flat with his or her feet elevated, unless contraindicated. Rationale: This position drains blood from the feet and legs and increases blood supply to the brain and central organs.

• Administer oxygen, as ordered by the practitioner Rationale: Administering oxygen helps prevent hypoxia.

• Administer blood, plasma, or other parenteral (IV) fluids, as ordered. Electrolytes will probably be added to the IV line. Rationale: These agents help to restore the client’s blood volume and fluid balance.

• Anticipate that vasopressor or other medications may be ordered. Rationale: Vasopressors increase BP. Other medications may be ordered to support circulation.

• Observe the client very closely Rationale: This can be a life-threatening situation.

Postoperative Hypertension

The client may also exhibit high blood pressure after surgery. This may be a result of withholding regular antihypertensive medications before surgery or may be caused by the trauma of surgery. Other causes include anxiety, pain, bladder or bowel distention, extreme chilling, hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), and some medications, particularly anticholinergics (e.g., atropine). One of the greatest dangers of hypertension is the risk of stroke. A diastolic reading of 100 mm Hg or above is a serious danger sign and immediate action must be taken. This is a particularly dangerous situation if the client also complains of blurred vision, dizziness, headache, or a decrease in level of consciousness. Treatment is symptomatic, if the cause of hypertension can be determined.

Hypoxia and Hypoxemia

Anesthetics and preoperative medications sometimes depress respirations (hypoventilation) and interfere with blood oxygenation (hypoxemia). This can lead to a lack of oxygen in the tissues, a condition known as hypoxia.Mucus blocking the trachea or bronchial passages also lowers the amount of oxygen entering the lungs, thereby reducing oxygen available for transport to the tissues. Oxygen and suction equipment should always be readily available for emergency use. Symptoms of hypoxia include dyspnea, rapid pulse, initial elevated BP followed by lowered BP, dizziness, and cyanosis. Some symptoms of shock, as listed in Box 56-4, are also related to hypoxia. Untreated hypoxia may lead to cardiac dysrhythmias. The most dangerous are the ventricular dysrhythmias.

Treatment for hypoxia depends on its cause. The client’s oxygen saturation is monitored with a pulse oximeter, a device that can be attached to the client’s nail bed (finger or toe) or earlobe. Usually, if the client’s oxygen saturation falls below 92% to 95% on room air, the client receives oxygen by nasal cannula, or by mask. Respiratory exercises can also help raise the oxygen saturation.

Hypothermia

Clients often complain of feeling cold after surgery. This is commonly associated with anesthesia. However, severechilling can cause hypoxemia, hypoxia, and cardiac stress. The following are significant signs and symptoms of postoperative hypothermia:

• Core temperature below 36.4°C (97.5°F). Core temperature may be obtained rectally. However, it is often recommended that it be obtained with the infrared tympanic temperature monitor.

• Chills, shivering, and “goose flesh,” unrelieved by warmed blankets

• Client complains of being extremely cold

• Confusion, disorientation, difficulty with speech. (Note: Because the client is recovering from anesthesia, it is difficult to determine if these symptoms are related to the anesthesia or to hypothermia.)

The nurse can apply warmed blankets without an order. If the client is found to be hypothermic, follow the instructions of the surgeon or other primary caregiver. Treatment in the PACU often involves the use of an overbed warmer. The overbed warmer or forced warm air device is usually available only in the PACU. In an extreme case, other treatments, such as warmed IV solution, may be given to raise the client’s core temperature.

Nursing Alert Severe hypothermia can be a life-threatening situation.

Neurologic Complications

Neurologic complications include delayed awakening (not regaining consciousness within 60 to 90 minutes), which may be caused by hypoxia, hypothermia, or electrolyte imbalances. Abrupt awakening may also occur. The client awakens in a confused and disorganized state of emergence excitement or delirium, which may be related to preoperative anxiety and to the type of surgery and age of the client. This may also be caused by certain intraoperative medications or by postoperative hypoxia, hypothermia, hypoglycemia, or dehydration. Prolonged paralysis may occur. Another complication is compartmental syndrome, ischemia in a confined space, such as the muscle compartments of the leg.This is caused by prolonged tissue pressure due to fluid and blood accumulation within the stationary fascia surrounding muscles. Treatment measures are instituted immediately, to prevent injury and to prevent permanent damage.

Nursing Alert In all postoperative complications, preoperative substance abuse must be considered. Many clients will not report drug or alcohol abuse and sudden withdrawal of the abused substance may lead to unexpected and dangerous postoperative complications.

NCLEX Alert The concepts relating to the physical and psychological changes of aging are commonly incorporated in an NCLEX scenario. You should be aware of aging factors that impact a client’s surgical risks and how you will approach the client/family’s pre- and postoperative needs for educational interventions. Other situations may reflect your ability to respond to pre- and postoperative difficulties.

Postoperative Discomforts

By the time the client returns from the PACU to the ambulatory receiving area or nursing unit, he or she is usually awake and aware of a number of discomforts. One measure used to relieve these discomforts is the administration of medications (see In Practice: Important Medications 56-2.)

Pain. Pain usually is the first postoperative discomfort the client notices. Pain is evaluated each time other vital signs are measured. Pain is usually most severe immediately after the client’s recovery from anesthesia. If the client receives medication early and subsequent doses are spaced properly, he or she usually will be relatively comfortable. Make sure the client is conscious and that his or her vital signs are stable before giving pain medications. Rationale: Analgesics are associated with respiratory depression, placing the client at high risk. Common pain medications are narcotics similar to those given preoperatively, in addition to analgesics such as ibuprofen.

Thirst. Thirst is almost always present postoperatively, usually because of a fluid decrease preoperatively, fluid loss during surgery, anesthetic recovery, and dryness caused by drying agents (e.g., atropine). Most clients receive IV fluids during surgery and immediately postoperatively. These fluids help prevent thirst, as does rinsing the mouth. In some cases, the client may be allowed to suck on a wet cloth, sip water, or suck ice chips in small amounts soon after surgery. Hard candy or chewing gum may also be permitted.

Abdominal Distention. Temporary halting of intestinal peristalsis allows gas to accumulate in the client’s intestine, causing abdominal distention (bloating). Handling of the intestines, anesthesia, drugs, lack of solid food, and restricted body movements also disturb normal peristalsis during surgery. Accumulated gas (flatus) may cause sharp pains that often are more distressing than incisional pain. Moving from side to side, sitting up in bed, or ambulating soon after surgery helps the client to expel flatus (gas). Delay offering fluids or solid food until bowel sounds have returned.

Key Concept If a client complains of distention or "gas pains," do not give ice or allow the client to take fluid through a drinking straw. Rationale: These actions tend to add air to the bowel and increase gas.

If the client’s discomfort increases and nursing measures bring no relief, insertion of a rectal tube may be ordered. Identification of bowel sounds and insertion of a rectal tube are described.Medications to relieve pain and intestinal gas also may be ordered to be given rectally or IM (see In Practice: Important Medications 56-2). These medications reduce stomach acid, slow peristaltic movements, and lessen heartburn and gastric distress. When the client is no longer NPO (nothing by mouth), these medications may be given orally. Simethicone (Mylicon) is also given orally to reduce gas.

During each shift, assess the client for the presence of bowel sounds by listening to his or her abdomen with a stethoscope. If bowel sounds have not returned within 2 to 3 hours following surgery, report this. If intestinal paralysis persists, a serious complication, paralytic ileus, may develop, in which the bowel has no peristaltic activity at all. Any ingested food, fluids, and digestive juices may accumulate and cause considerable discomfort. This may be life threatening because a bowel obstruction may occur and the bowel may rupture. A nasogastric tube is inserted to decompress or empty the stomach of its contents and may provide relief, but does not resolve the problem. Emergency surgery is often required to eliminate a bowel obstruction.

Key Concept Symptoms of a bowel obstruction are lack of bowel movement, with presence of bowel sounds. Symptoms of a paralytic ileus are absence of bowel motility and absence of bowel sounds. In addition, the client complains of bloating, gas pains, nausea, and vomiting. The client should not take anything by mouth until this situation is resolved.

IN PRACTICE IMPORTANT MEDICATIONS 56-2

EXAMPLES OF IMPORTANT POSTOPERATIVE MEDICATIONS

Postoperative Nausea (Antiemetics)

• aprepitant (Emend)—may be given preoperatively or during surgery to prevent postoperative vomiting

• dolasetron mesylate (Anzemet)—if client is unable to swallow tablets, injectable form may be diluted in juice and taken orally Dosage remains the same.

• granisetron HCl (Kytril, Sancuso)

• hydroxyzine (Vistaril)—helps to control nausea and allows reduction in use of opioids. Is also given for anxiety or pruritus (itching). Available in oral tablets, syrup, or injectable forms.

• metoclopramide (Reglan)—used for postoperative nausea when nasogastric suction is undesirable. Available in oral tablets or syrup, intramuscular (IM), and intravenous (IV) forms. May be given at the end of surgery as a preventive measure.

• ondansetron HCl (Zofran)—used to prevent further vomiting or when vomiting must be avoided (oral); prophylactic use (parenteral). Available in tablets, orally disintegrating tablets or solution, injectable.

• palonosetron HCl (Aloxi)—can be used for up to 24 hours postoperatively given IV.

• prochlorperazine (Compazine, Stemetil)—given for severe postoperative nausea. Available in injectable, syrup, rectal suppository and sustained-release tablet forms.

• promethazine HCl (Phenadoz, Phenergan)—classified as a dangerous drug, used for preoperative, postoperative, and obstetric sedation and as an antiemetic.

• trimethobenzamide HCl (Tigan)—given to prevent emesis. Available in capsules, injectable form, and suppositories. Can be used for children.

Nursing Considerations

• Allergy to any drug may cause anaphylaxis.

• Side effects of most antiemetics include drowsiness, dizziness, lethargy, dry mouth and respiratory passages, orthostatic hypotension, constipation.

• If the client has glaucoma, this condition may be aggravated by drugs. Certain other physical conditions preclude the use of specific medications. Many medications are carried across the placenta or in breast milk and must be used cautiously in pregnant or nursing women. The provider must consider these factors when ordering medications.

Postoperative Constipation

Stool Softener

• docusate sodium (Colace, Diocto-C)

Laxatives

• bisacodyl (Dulcolax)

• docusate, casanthranol (Peri-Colace)

• lactulose (Cephulac)

• magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia [MOM])

• senna (Senokot)

Bulk-Forming Agents

• polycarbophil (FiberCon)

• psyllium (Metamucil, Genfiber): chewable pieces, effervescent powder, granules, powder, wafers

Nursing Considerations

• Make sure bowel sounds are present before administration

• May stimulate excessive gastrointestinal (GI) motility Avoid administering to clients with GI bleeding, obstruction, perforation.

• May endanger abdominal suture line.

• Be alert for diarrhea.

• Monitor older clients for extrapyramidal side effects, due to a possible paradoxical reaction (opposite reaction).

Postoperative Flatus

• famotidine (Pepcid)

• ranitidine (Zantac)

• simethicone (Gas-X, Mylicon, Flatulex)

Nursing Considerations

• Make sure bowel sounds are present before administration.

• Be alert for adverse side effects, including constipation, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and skin lesions.

Other

Bacitracin is an antibiotic, often used topically to prevent or treat incisional infections.

Nausea. If the client complains of nausea, give ordered medications to prevent emesis. Often such medications are given IM or rectally. Some also may be given IV (see In Practice: Important Medications 56-2). It is important to prevent vomiting, if at all possible, because this can cause added complications. In reports, postoperative nausea and vomiting may be abbreviated to PONV.

Urinary Retention. Many clients leave the OR with a urinary catheter in place. After its removal, the client may have difficulty voiding because of anesthesia’s effects. To aid urination, help the client sit upright, pour warm water over the vulva or penis, place the client’s hands in warm water, and run water so the client can hear it. If the client has not voided within 8 hours after surgery, catheterization may be ordered. This client is usually on intake and output (I&O) measurements. Monitor the amount of fluid taken through IV infusion and by mouth to judge the amount of urine likely to be accumulating in the bladder. I&O should be approximately equal.

Key Concept The postoperative client may be permitted to take a sitz bath, a warm shower; or a warm tub bath. This often facilitates voiding and defecation.

Constipation. Disruption of the normal diet and daily elimination schedule, drying medications (e.g., atropine), pain medications (particularly morphine or codeine), inactivity, and slowed peristalsis because of anesthesia’s effects may cause constipation (decreased frequency of stools, difficult passage, or hard, dry stools). As soon as the client can eat or drink, encourage fluid intake, specifically fruit juices.

Help the client to the commode or bathroom. Encourage ambulation, to stimulate peristalsis. Some physicians routinely prescribe a stool softener (e.g., Colace), both pre- and postoperatively. A laxative may be given as well to prevent constipation (see In Practice: Important Medications 56-2.)

Restlessness and Sleeplessness. The client may be restless and have difficulty sleeping in the postoperative period. Make every effort to relieve these symptoms through ordinary nursing measures. Medications to promote sleep and relieve pain also play an important role.