Period of the Embryo

When it is fully implanted, the developing organism is called an embryo (Fig. 65-4). The outermost cell layer that surrounds the embryo and fluid cavity is called the chorion. Some of these outer cells send out projections (chorionic villi), which are the “roots” through which the developing embryo receives its oxygen and nourishment from the mother.

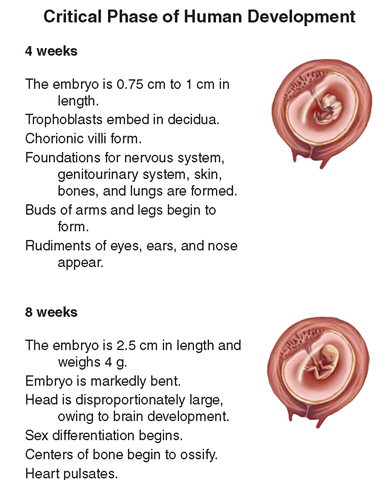

Critical Period of Development. During the period of the embryo, which lasts until the eighth week after conception, the embryo is in what is called the critical phase of human development. During these weeks, all the organs and structures of the human are formed and are most susceptible to damage (Fig. 65-5).

Key Concept The first 8 weeks of pregnancy are the critical period of human development; during this time, all major systems of the embryo develop.

The embryo, and to a lesser degree the fetus, is vulnerable to a number of potentially harmful influences that could result in congenital (literally, “born with”) defects. Genes determine the basic embryonic structure; therefore, a defective gene may be responsible for certain congenital defects. Environmental factors, such as tobacco or alcohol use, also can cause congenital anomalies, also known as birth defects.

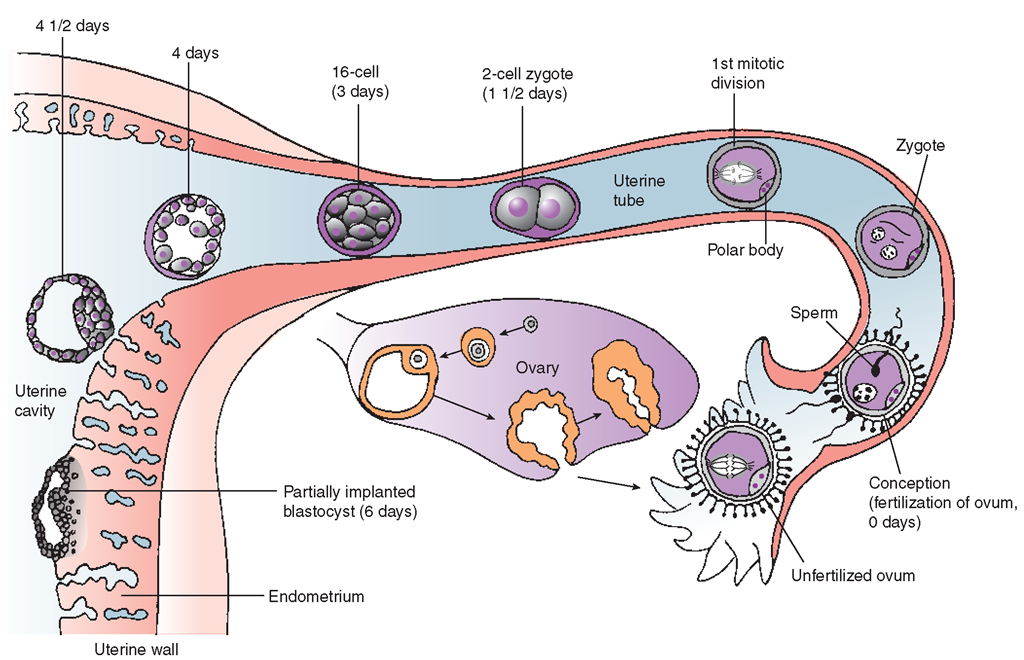

FIGURE 65-3 · Early human development and implantation.

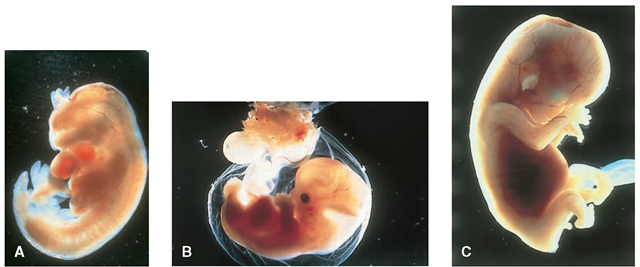

FIGURE 65-4 · (A) A 4-week embryo. (B) A 5-week embryo. (C) A 6-week embryo.

NCLEX Alert The terminology associated with pregnancy is related to specific nursing knowledge and, therefore, certain applicable nursing interventions. It is important that the student learn to associate specific levels of the pregnant uterus with the responsibilities of observance, teaching, and documentation.

Period of the Fetus

The period of the fetus lasts from the beginning of the ninth week after fertilization through birth, which is usually at about the end of the 40th week of pregnancy.

FIGURE 65-5 • Critical period of development.

This is a period of increasing growth, differentiation, and functional development of the tissues that appeared during the embryonic period. At about 20 weeks of gestation, the fetus becomes viable (having some chance of life outside the uterus).

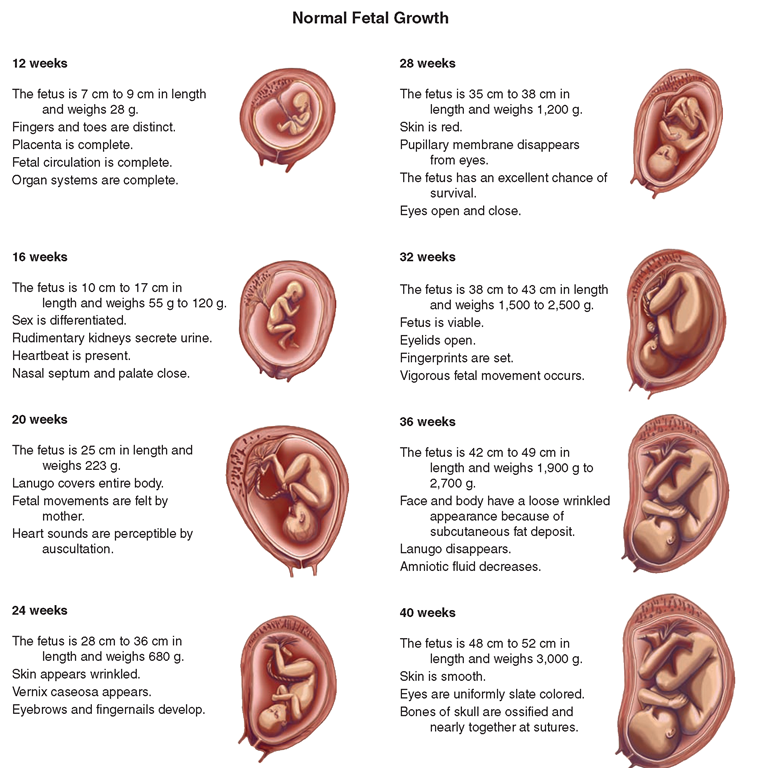

Normal fetal growth and development follow a definite and predictable pattern (Fig. 65-7). Growth and development, before and after birth, follows the cephalocaudal (head to toe) principle.

Heredity and the mother’s nutritional status have some influence on the growth of the fetus. A newborn weighing 10 pounds (4,540 g) or more is often difficult to deliver; however, the smaller the child is at birth, the less likely his or her chances are for survival. A newborn weighing less than 2.2 pounds (1,000 g) is considered immature. With current newborn intensive care units, however, the chances for survival of very small newborns are improving.

Placenta and Umbilical Cord. The fetus’ chorionic villi eventually meet with an area of uterine tissue to form the placenta (Fig. 65-8), an organ with a rich blood supply that:

• Supplies the developing organism with food and oxygen

• Carries waste away for excretion by the mother

• Slows the maternal immune response so that the mother’s body does not reject the fetal tissue

• Produces hormones that help maintain the pregnancy

The fetal blood is entirely within blood vessels. Blood vessels may be found within the fetus’ chorionic villi. These villi within the placenta are bathed in a pool of maternal blood, making this area the only place in the body (with the exception of the heart) where blood is not contained within blood vessels.

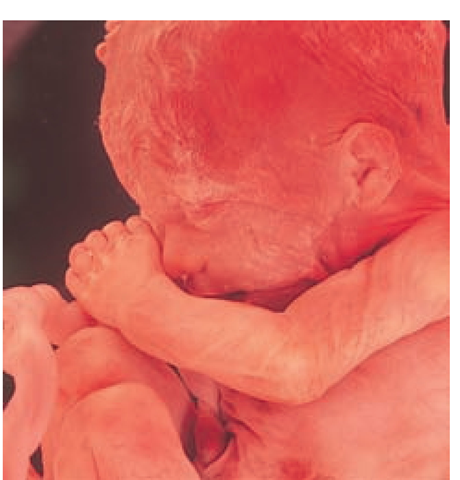

FIGURE 65-6 · A 12- to 15-week fetus.

FIGURE 65-7 · Different stages of fetal development.

The villi are suspended in this pool of nourishing blood from the mother, much like a cluster of grapes could be dipped in a bowl of water that is continuously circulated by being pumped into the bowl and then drained.

Using its chorionic villi within the placenta, the fetus secures its oxygen and food directly from the mother’s blood, instead of using its own lungs and digestive system. The absorption of nutrients, excretion of wastes, and exchange of gases occur across the walls of the placental villi and the fetal blood vessels they contain. The fetal and the maternal blood are separate.

By term, the placenta is approximately 15 to 20 cm in diameter, 2 to 3 cm thick, and weighs between 500 and 600 g. The weight of the placenta is about one-sixth the weight of the infant, if both are healthy.

The umbilical cord connects the fetal blood vessels contained in the villi of the placenta with those found within the fetal body. The umbilical cord consists of two arteries and one large vein twisted around each other. The umbilical cord is approximately 20 inches (51 cm) long. A soft, jellylike substance called Wharton’s jelly protects the cord, which enters the fetus’ body approximately in the middle of the abdomen at the umbilicus, or navel.

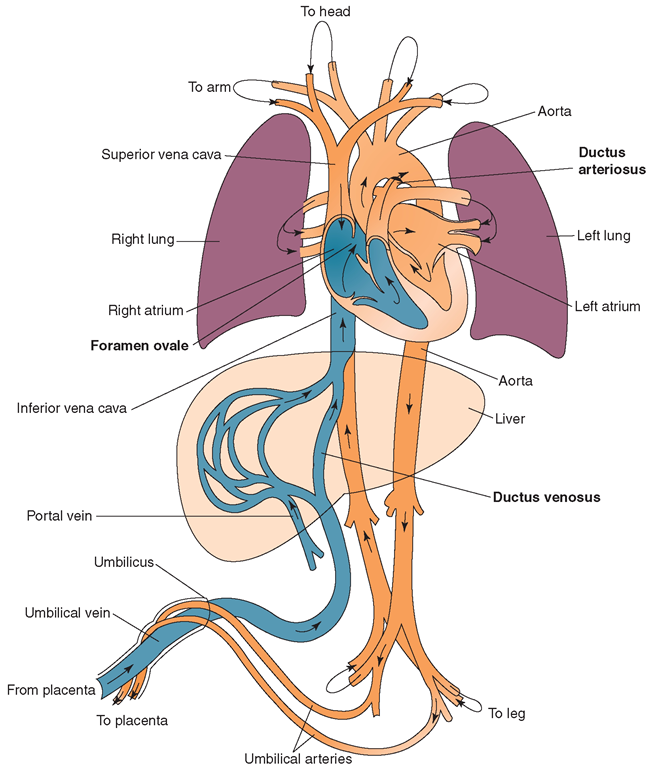

Fetal Blood Circulation. Fetal circulation differs from newborn and adult circulation (Fig. 65-9). The woman’s blood supplies food to—and carries wastes away from—the fetus. The uterus expels the placenta, which is also called the afterbirth, following the newborn’s delivery. While the fetus is in utero, the placenta returns deoxygenated (low in oxygen) blood from the fetus to the mother through the two umbilical arteries.

FIGURE 65-8 · Placenta.

The placenta returns oxygenated (oxygen-rich) blood to the fetus via a single vessel, the umbilical vein. This process is an exception to the usual pattern, in which all arteries carry oxygenated (bright-red) blood, and all veins carry deoxygenated (dark-red) blood. Some oxygenated blood from the umbilical vein passes through the fetal liver, but most of it enters the fetus’ inferior vena cava through the ductus venosus. This short duct is found only in the fetus, and atrophies after birth. From the inferior vena cava, the blood flows into the fetus’ right atrium.

Because the fetal lungs are not yet functioning, most of the blood is shunted to the heart’s left atrium. This shunt occurs through another fetal structure, the foramen ovale, which is an opening between the right and left atria. This structure permits most of the blood to bypass the right ventricle. A small amount of blood passes from the right atrium to the right ventricle, and makes its way into the pulmonary artery. This blood is then shunted through the ductus arteriosus, a connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta that allows shunting of blood around the fetal lungs.

Normally, with the newborn’s first few respirations, the lungs expand as soon as the pressure within the chest alters. The foramen ovale closes, and the ductus arteriosus and ductus venosus shrivel and become fibrous ligaments. Congenital heart defects in a child occur when these events do not take place after birth.

NCLEX Alert Transference from fetal circulation to adult type circulation is a common cause of post-birth problems. The nurse, who is generally caring for the newborn in the mother’s room, must be aware of a wide variety of post-birth anatomical complications and their nursing interventions.

Membranes and Amniotic Fluid. In the earliest human developmental stage, the chorionic plate that gives rise to the villi resembles a fuzzy ball. As the embryo grows, most areas of the villi atrophy, leaving only a disc of villi that develops into the placenta. The rest of the chorion becomes a smooth outer membrane for the embryo. Inside it, other cells eventually form a fluid-filled sac, the amnion, in which the fetus floats. The amnion is the inner membrane surrounding the fetus. These two membranes form a tough, protective bubble for the developing embryo and fetus, protecting it from organisms that might infect the mother’s cervix. In addition, the membranes are important to hormone production and also play a role in the onset of labor. The amniotic fluid, kept inside the amnion, performs the following functions:

• It cushions the fetus against injury.

• It regulates temperature.

• It allows the fetus to move freely inside it, which allows normal musculoskeletal development of the fetus.

FIGURE 65-9 · Fetal circulation. Notice the two arteries, the one vein, the ductus venosus, the ductus arteriosus, and the foramen ovale, which are unique to fetal circulation.

In late pregnancy, the amniotic fluid is made up primarily of fetal urine and fetal lung fluid. Near term, the fetus swallows almost 400 mL of amniotic fluid each day and then excretes it in the urine; therefore, a defect in either the ability of the fetus to swallow or in its kidney function can dramatically change the quantity of amniotic fluid. The quantity of amniotic fluid increases to about 1,000 mL by 37 weeks of gestation; decreases slowly until 40 weeks; and then decreases much more quickly if the baby is not born by the end of the 40th week. Because of this predictable pattern in the quantity of fluid, one measurement of post-term fetal well-being is the volume of amniotic fluid.

Changes in a Woman’s Body During Pregnancy

Many of the changes in a woman’s body during pregnancy can be seen externally. However, there are also many changes in her internal structure and function. Some of these changes are caused by the growing size of the fetus, but even more changes result from the unique hormonal environment caused by pregnancy. These changes begin to occur soon after fertilization, when the production of hormones changes from that of a normal menstrual cycle.

Signs of Pregnancy

The signs of pregnancy are grouped into three categories (Box 65-1).

Presumptive and probable signs are primarily caused by the hormonal changes that occur during pregnancy. Most presumptive signs appear early and are subjective; that is, they may be noted only by the woman. When a woman experiences these symptoms, she may assume that she is pregnant. However, these symptoms could indicate a condition other than pregnancy.

BOX 65-1.

Signs of Pregnancy

Presumptive: possible signs, appear in first trimester, often only noted subjectively by the mother (e.g., breast changes, amenorrhea, morning sickness) Probable: likely signs, appear in first and early second trimesters, seen via objective criteria, but can also be indicators of other conditions (e.g., hydatidiform mole)

Positive: proof exists that there is a developing fetus in any trimester; objective criteria seen by a trained observer and/or diagnostic studies (e.g., ultrasound)

Probable signs also appear early in pregnancy, but they are more objective. Often, both healthcare personnel and the client herself can observe probable signs. Although probable signs are more definite, they still are not absolute.

Only the positive signs of pregnancy provide proof that there is a developing fetus.

Key Concept Pregnancy is not confirmed until the existence of a fetus can be proved.