The melon-headed whale is one of a group of small, dark-colored whales that are often referred to as “blackfish.” It is only recently that much has been known about these little whales because they generally occur far offshore and in many areas they avoid approaching vessels.

I. Characters and Taxonomic Relationships

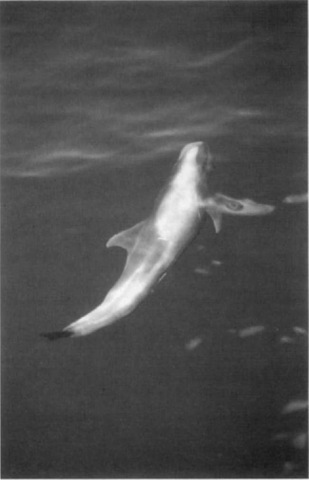

The melon-headed whale (Fig. 1) is mostly dark gray in color with a faint darker gray dorsal cape that is narrow at the head and dips downward below the tall, falcate dorsal fin. A faint fight band extends from the blowhole to the apex of the melon. A distinct dark eye patch, which broadens as it extends from the eye to the melon, is often present and gives this small whale the appearance of wearing a mask. The lips are often white, and white or light gray areas are common in the throat region and stretching along the ventral surface from the leading edge of the umbilicus to the anus. At sea, this species is difficult to distinguish from the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata). It differs externally from the pygmy killer whale by having a more pointed or triangular head and sharply pointed pectoral fins. Both of these characters are difficult to recognize at sea unless these small whales are seen from above. Experienced observers often rely more on behavioral than physical characters to separate these two blackfish in the field. In stranded specimens, the melon-headed whale can be distinguished from all other blackfish by its high tooth count, 20 to 26 per row, compared to generally less than 15 teeth per row for pygmy killer whales.

Melon-headed whales are about 1 m in length at birth (Bryden et al., 1977) and continue to increase in length until they are 13 to 14 years old. Asymptotic length for males (2.52 m) is greater than for females (2.43 m), and males also have comparatively longer flippers, taller dorsal fins, and broader tail flukes (Best and Shaugbnessy, 1981; Miyazaki et al, 1998). In addition, some males exhibit a pronounced ventral keel that is found posterior to the anus. The longest specimen reported was a 2.78-m female that stranded in Brazil (Lodi et al, 1990). A 2.64-m male that stranded in Japan weighing 228 kg is the heaviest specimen reported (Miyazaki et al, 1998).

The skull of the melon-headed whale is typically delphinid in shape, with the exception of a very broad rostrum and deep antorbital notches. It is similar to the skull of the common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), but the teeth of the melon-headed whale are much smaller and appear more delicate. The high tooth count of this species separates its skull from those of other small beakless whales.

The melon-headed whale is a member of the subfamily Glo-bicephalinae where it is closely allied with the very similar pygmy killer whale and the larger pilot whales (Globicephala inelas and G. macrorhynchus). Investigations regarding the interrelations of these species have yet to produce definitive results.

II. Distribution and Ecology

Melon-headed whales are found worldwide in tropical to subtropical waters. They have occasionally been reported from higher latitudes, but these sightings are often associated with incursions of warm water currents (Perryman et al, 1994). They are most often found in offshore, deep waters, and nearshore sightings are generally from areas where deep oceanic waters are found near the coast. Squids appear to be the preferred prey of this species, but small fish and shrimps have also been found in their stomachs (Jefferson and Barros, 1997).

III. Behavior and Life History

Melon-headed whales are most often found in large aggregations, a behavior that separates them from the very similar pygmy killer whale. They are often seen in large mixed aggregations with Fraser’s dolphin (Lagenodelphis hosei). They have also been sighted in mixed herds with spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) and common bottlenose dolphins (Dolar, 1999). Although they are reported to flee from approaching vessels in the eastern Pacific, it is not uncommon for melon-headed whales to briefly ride the bow wave of passing ships in other areas. They may bow ride for longer periods if the vessel slows to a speed of a knot or less.

Mass strandings of melon-headed whales have been reported on several occasions; the cause of the strandings is unknown. In two strandings from Japan and one in Brazil, the specimens had high loads of internal parasites, which might have caused some animals to strand. It has also been suggested that mass strandings of these highly social animals may be caused by a panic response in the school when a few members accidentally strand (Miyazaki et al, 1998).

IV. Interactions with Humans

When captured live and transferred to aquariums, melon-headed whales have not thrived and have been difficult to train. They have been aggressive toward keepers and have caused in- juries by ramming individuals with their heads or raking them with their teeth. In Hawaiian waters, melon-headed whales have approached divers in an aggressive manner, swimming rapidly and opening and closing their jaws causing an audible clapping sound. Swimmers should be cautious if entering the water around these small whales.

Figure 1 Melon-headed whales, Peponocephala electra, occur around the world in subtropical and tropical waters.

Melon-headed whales are taken in small numbers in harpoon and drift net fisheries in the Philippines (Dolar, 1994), Indonesia, Malaysia, and in the Caribbean near the island of St. Vincent. Schools of melon-headed whales have been taken in the drive fishery operated from the port of Taiji, Japan. On rare occasions, a member of this species is taken in the purse seine fishery for yellow-fin tuna in the eastern tropical Pacific. Because most of these fisheries are not extensively monitored, the effect of these direct and incidental takes on local populations is unknown.