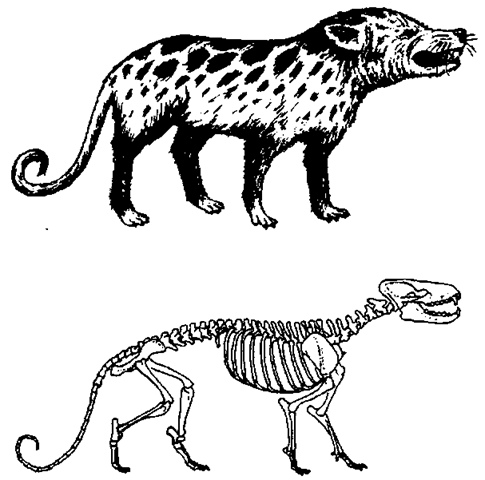

Mesonychians are an extinct group of four-footed land » mammals that lived in the Early Tertiary and are rec-. ognized by paleontologists to be the closest relatives of whales. This hypothesis has, however, been difficult to reconcile recently with the molecule-based hypodieses that cetaceans may be most closely related to hippos. Mesonychians were unique because they possessed hooves like many plant-eating mammals, but sharp teeth like many carnivorous mammals. Mesonychians obtained a relatively wide distribution throughout the globe; their fossils are found in North America, Europe, and Asia in rocks dating from the early Paleocene through the end of the Eocene, an interval of about 30 million years. Despite a relatively wide geographic distribution, mesonychian fossils remain some of the rarest elements of early Tertiary faunas. Most species have been described only from jaws and teeth but several are also well known from skulls and postcrania. The first appearance of mesonychians in the fossil record precedes the first appearance of whales by approximately 10 million years. Unlike whales, mesonychians became completely extinct around the end of the Eocene. Mesonychians are significant because they provide scientists with a hypothesis of how whale ancestors may have looked before they left land for a life in water (Fig. 1).

I. Origins and Relationships

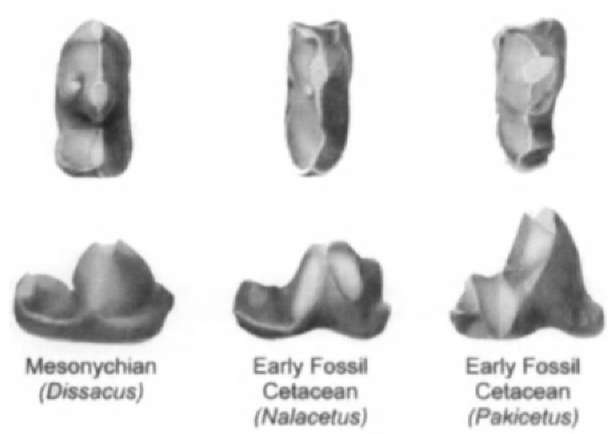

Mesonychians were first named for specimens discovered in North America in 1874. Since then about 20 genera of varying sizes have been recognized, none of which contains many species (Table I). Mesonychians were initially thought to belong to the order Creodonta, an extinct group of mammals closely related to the Carnivora. This was proposed because mesonychians are similar to both creodonts and carnivorans in having tall, pointed lower molar teeth (Fig. 2). Paleontologist Leigh Van Valen argued in 1966, however, that because mesonychians also have hooves and certain other features of the skull, their anatomy more closely resembles that of hoofed mammals. Hoofed mammals include, among other species, artiodactyls, perissodactyls. and all of their extinct relatives. Van Valen argued that as mesonychians evolved they diverged from other hoofed mammals, which are primarily herbivorous with short, square teeth and independently developed dental similarities resembling those of certain meat-eating animals like carnivorans. The teeth of mesonychians also resemble the teeth of early whales, also thought to have been carnivorous, not only because dieir living descendants are carnivorous but because of the sharp pointy shape of their teeth. Mesonychians thereby became an important fossil intermediate to link a carnivorous group like whales to living and extinct hoofed mammals, which primarily eat plants.

Figure 1 Skeleton of one of the better known mesonychian fossils, Mesonyx (bottom), and an artist’s (Luci Betti) reconstruction of how it might have looked (top). This animal was approximately the size of a large dog.

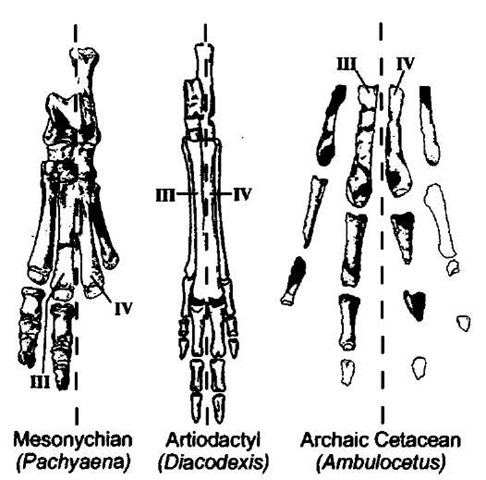

Van Valen’s hypothesis has since been corroborated by phy-logenetic analyses of mammals that show that mesonychians are the extinct species mostly closely related to whales and that artiodactyls are the living mammals most closely related to this whale + mesonychian group. The features that mesonychians and whales share are primarily those of the dentition (Fig. 2) and the skull. Mesonychians, whales, and artiodactyls, however, all share cranial and postcranial features in common, including possession of a paraxonic foot (Fig. 3). Paraxonia is a specially evolved condition in these mammals in which the weight of the body is transmitted along an imaginary line between digits three and four (Fig. 3). Digit one (which is equivalent to the thumb or big toe in a human) is reduced such that it is not weight bearing and in some animals it is completely lost.

TABLE I

Mesonychian Taxa and Their Stratigraphic and Geographic Ranges”

|

Genus |

Stratigraphic range |

Geographic range |

|

Yantanglestes |

Paleocene |

Asia |

|

Hukoutherium |

Paleocene |

Asia |

|

Dissacusium |

Paleocene |

Asia |

|

Ankalagon |

Paleocene |

North America |

|

Sinonyx |

Paleocene |

Asia |

|

Dissacus |

Paleocene-Eocene |

North America. Asia. Europe |

|

Pachyaena |

Paleocene-Eocene |

North America. Asia, Europe |

|

Jiangxia |

Paleocene |

Asia |

|

Mongolonyx |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Harpagolestes |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Hessolestes |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Synoplotherium |

Eocene |

North America |

|

Mesonyx |

Eocene |

North America, Asia |

|

Guile stes |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Mongolestes |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Hapalodectes |

Paleocene-Eocene |

North America, Asia |

|

Hapalorestes |

Eocene |

North America |

|

Metahapalodectes |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Lohoodon |

Eocene |

Asia |

|

Honanodon |

Eocene |

Asia |

When generating phylogenetic analyses of Cetacea on the basis of DNA it is difficult to evaluate the full impact of mesonychians because they are completely extinct and information about their genes remains unknown. Mesonychians may nevertheless have been a very pivotal group.

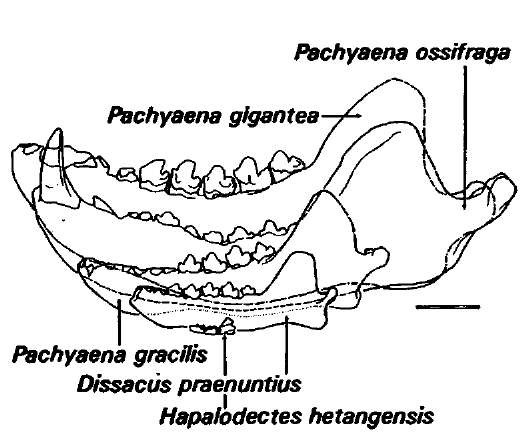

II. Anatomy and Function

Study of the best-preserved skeletons of mesonychians, primarily the genera Dissacus, Pachyaena, Mesonyx, and Sinonyx, indicates diat these animals evolved the ability to run fast relative to their Early Tertiary contemporaries. Paleontologists surmise this from the structure of mesonychian vertebral columns, limbs, ankles, and feet. Many of the joints of these mammals have evolved to restrict motion of the limbs to flexion and extension as is typical of many cursorial animals. In so doing many mesonychians sacrificed having a wide range of mobility of their joints for having increased joint stability within a limited range of mobility. This condition may be advantageous for an animal that is moving at high speeds across a terrestrial substrate. Study of the vertebral column of the mesonychian genus Pachyaena indicates that it was a stiff-backed runner, meaning that its vertebral column did not exhibit much motion side to side or up and down during running. This feature characterizes many large-bodied hoofed mammals. and observation of this functional similarity is another shared feature of mesonychians and hoofed mammals. These functional characters are perhaps best understood in the genus Pachyaena (Fig. 4), which includes some of the larger mesonychian species, and which in one species is estimated to have had a body weight of approximately 400 kg. The earliest whales, therefore, may have evolved into fully aquatic animals by modifying a body that had originally evolved for running on land.

The dentition of mesonychians is simplified such that they have lower premolars and molars that resemble each other in exhibiting three main cusps (Fig. 2). Upper teeth are simplified and triangular in all taxa. The morphology of the lower dentition resembles that seen in living piscivorous mammals such as seals and toothed whales, and some paleontologists have argued that mesonychians may have been piscivorous also. Mesonychians had a chewing mechanism that was restricted largely to or-thal motions (up and down as opposed to side to side). Carnivorans chew in a similar fashion; however, the mesonychian chewing mechanism appears to have been less tightly interlocking than that of carnivorans as evidenced by the variable position of tooth-wear facets on mesonychian molars (Fig. 2).

Studies of endocasts (molds made from the inside of the skull to estimate brain size and shape) of mesonychians indicate that these animals had more specialized brains than contemporaneous hoofed mammals and carnivorans. In particular, mesonychians had reduced olfactory lobes, suggesting a decreased reliance on the sense of smell.

Figure 2 Right lower molars of a mesonychian and primitive whales for comparison. The top row of teeth is shown from a view of the chewing surface, and the bottom roto of teeth is shown from a view from the cheek side.

III. Paleoecology

Because of their strange combination of hoofed mammal and camivoran characteristics, mesonychians have no close modern analogue, something that makes reconstruction of their paleoecology particularly challenging. In the Early Tertiary (Paleocene and Eocene) faunas in which mesonychians are found, they are among the largest predators and some of the largest mammals. Carnivorans did not reach the size of mesonychians until millions of years later. It was mesonychians and not carnivorans that filled

the role of pursuit predators in the Eocene. Paleontologists continue to grapple widi the question of why mesonychians have a cursorially modified skeleton. Was it important for defensive (escape) or offensive (attack) behavior? The diet of mesonychians has also been difficult to determine, with suggestions ranging from omnivory (a varied diet) to piscivory, molluscivory (mol-lusks), and camivory. By further researching both phylogenetic and functional questions, paleontologists may better understand why whales left land and returned to water.

Figure 3 Feet of a mesonychian, a fossil artiodactyl, and a fossil cetacean all shown as if looking down on the top surface of the foot. All exhibit a paraxonic foot, i.e., one in which the weight of the body passes along an imaginary line (dotted) between digits three and four and in which the foot is largely symmetrical.

Figure 4 Lower jaws of four different mesonychian species indicating the range of size variation in this group. The species Dissacus praenuntius was approximately the size of an average dog. Scale bar: 5 cm.