The baculum (os penis) is a bone in the penis of Insec-tivora, Chiroptera, Primates, Rodentia. and Carnivora; it is absent from Cetacea and Sirenia. The corresponding element in females is the os clitoridis. In marine mammals the baculum and osclitoridis have been studied mainly in pinnipeds.

The baculum develops in the proximal part of the penis in association with the fibrous septum between the paired corpora cavernosa penis or in their fibrous noncavernous portion; in the dog, centers of ossification on left and right sides fuse early in development. The developing baculum grows distally above the urethra and thickens. The bacular base becomes firmly attached to the corpora cavernosa and the fibrous tunica albuginea which surrounds them. In rodents, the bacular shaft is true bone and includes hemopoietic and fatty tissue in the enlarged basal portion.

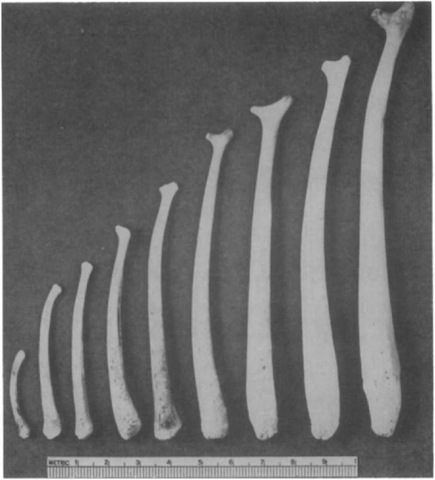

During development, bacula may become progressively straighter (southern elephant seal, Mirounga leonina; northern fur seal, Callorhinus ursintis) or curved (harbor seal, Phoca vi-tulina; hooded seal, Ctjstophora cristata). Pinniped bacula grow throughout life in mass and thickness (particularly at the basal end) but not in length. Growth is rapid around puberty and may exhibit a secondary spurt at social maturity (e.g., Cape fur seal, Arctocephalus p. pusillus). In Otariidae, the bacular apex, shaft, and base differ from one another in their growth patterns.

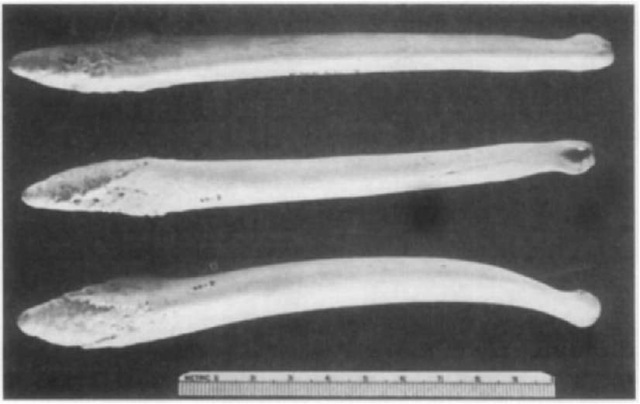

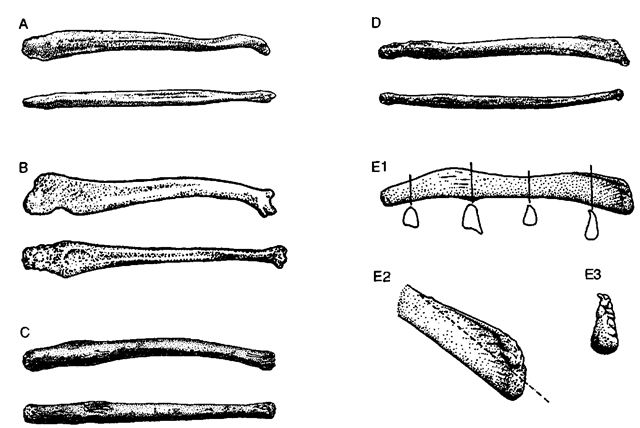

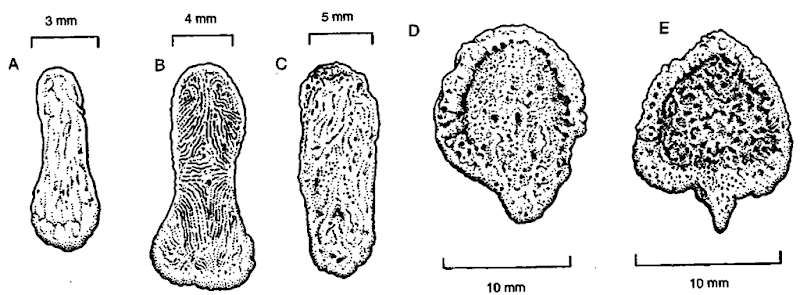

The urethral groove is shallow to absent in bacula of marine mammals (Fig. 2; lower drawings in Figs. 3A-3D). Typically the baculum is slightly arched dorsally (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). The apex is relatively elaborate in Mustelidae and Otariidae (Fig. 4) and is simple in Ursidae and Phocidae. In adults of some Antarctic seals a prominent crest develops on the anterior dorsal surface, however (upper drawing in Fig. 3D; Fig. 3E). In some species the bacular apex has a prominent cartilaginous cap (e.g., hooded seal). Bacula are variable in size, shape, cross section, and specific structural features within species (even among animals of the same age). For example, a dorsal keel may be present or absent in adult southern elephant seals; processes on the shaft near the apex may be present or absent in adult California sea lions (Zalophus californiamis); and bacula may be bilaterally asymmetrical or slightly twisted (Fig. 3D; Fig. 3E1).

Bacula of Carnivora are fairly large. In pinnipeds and indeed among all mammals, walruses (Odobemts rosmarus) have the largest baculum both absolutely (to 62.4 cm in length and 1040 g in mass) and relatively (18% of standard body length). Bacular length in a large polar bear (Ursus maritimns) was 17.3 cm. Interspecific differences in bacular size in mammals have been linked to aquatic copulation, copulatory duration or pattern, mating strategy, and risk of fracture. Fractures possibly result from accidents (e.g., falls in walruses), sudden movements during intromission (e.g., in aquatically copulating species such as Caspian seal, Pusa caspica), or aggressive social interactions (e.g., fights between adult male sea otters, Enhy-dra hitris). Healed fractured bacula have been observed in several species.

Bacula likely serve several functions, including (1) a mechanical aid to intromission (especially in the absence of full erection) or maintenance of intromission in aquatic copulations and (2) to initiate or engage neural or endocrinological responses in females. Bacular form and diversity reflect multiple functions and hence have multiple adaptive explanations.

Bacular characteristics have been informative in phylogenetic studies of Otariidae and Mustelidae, suggesting needed taxonomie revisions and revealing interesting developmental and evolutionary trends.

Bacular size can aid in estimating age, and bacula grow quickly at puberty so are a good indicator of when it occurs. Bacular growth may be affected by pollutants, so bacular size and form may also be informative in studies on pollution biology.

Figure 1 Developmental changes in bacular size and shape, illustrated by representative bacula from northern fur seals ranging in age from newborn (left) to 8 years (right).

Figure 2 The baculum of an adult sea otter shotting general form and elaborate apex (center); apex is to the right. Top, dorsal view; center, ventral view; bottom, right lateral view.

Figure 3 Bacula of adult (A) polar bear, (B) sub-Antarctic fur seal (Arctocephalus gazella), (C) Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus), (D) crabeater seal (Lobodon carcinophaga), and (E) Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii). Bacula in A-D are shown in right lateral (upper) and ventral (lower) views and are not shown to the same scale. El: baculum in right lateral view; note cross-sectional shapes at the indicated points. E2; oblique view (right side) of the bacular apex (same baculum); dashed line emphasizes how much growth occurs in the crest (above the line) following sexual maturity. E3: apical view (dorsal surface above; same baculum). A from Didier (Mammalia 15,11-22; 1951); Bfrom Didier (Mammalia 16, 228-239; 1952); Cfrom van Bree (Mammalia 58, 498-499; 1994); Dfrom Didier (Mammalia 17, 21-26; 1953); and Efrom Morejohn (J. Mammal. 82, 877-881; 2001).

Figure 4 Structural diversity of the bacular apex in Otariidae (dorsal surface up), illustrated by adult specimens of (A) unknown species of southern fur seal (Arctocephalus), (B) northern fur seal, (C) California sea lion. (D) Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea), and (E) Hooker’s sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri). From Morejohn (1975).