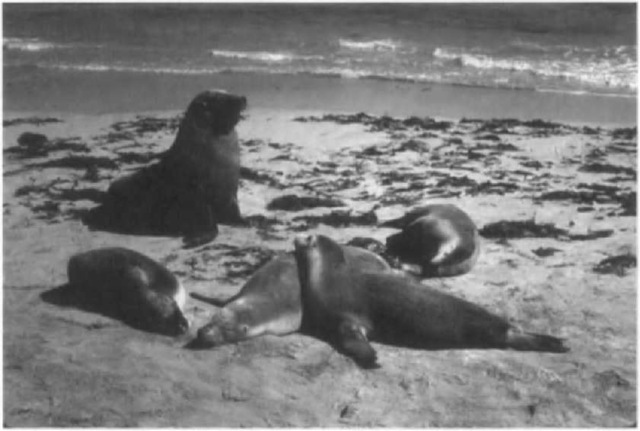

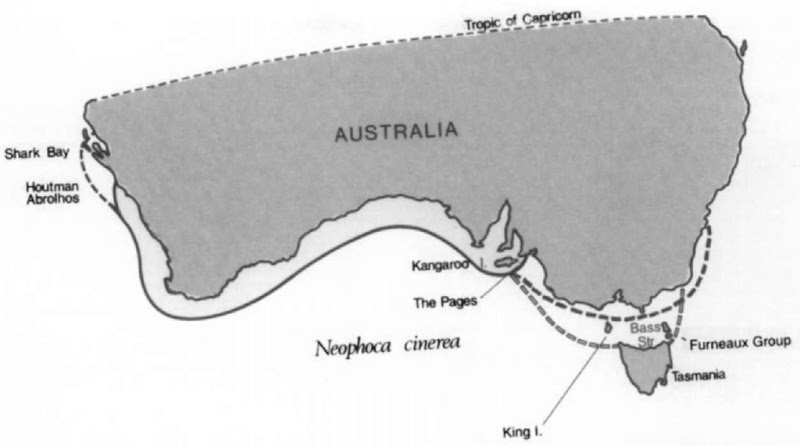

The indigenous Australian sea lion (Fig. 1) is one of the worlds rarest and most unusual seals: rare in terms of very small numbers and unusual in its having a sesqui-ennial reproductive cycle. It is also a temperate species, inhabiting waters around much of the southern part of the island continent between latitudes 28 and 38°S. Its current breeding range extends from Houtman Abrolhos (29°S,114°E) in Western Australia to The Pages Islands (36°S.138°E), just east of Kangaroo Island. South Australia, with stragglers reaching central New South Wales on the east coast (Fig. 2).

I. Color and Size

At birth the pups are a dark chocolate brown to charcoal gray in color, which changes to the smoky gray (hence the specific name cinerea) and cream adult color after the postnatal molt. Females retain this coloration throughout life, but males gradually develop a brownish-black coat with increasing age. Males of breeding age have a cream patch on the back of the head and nape of the neck. This species has flattened guard hairs but no underfur—the pelage apparently being adapted to a temperate environment. It also has a relatively thin layer of blubber beneath the skin, about 2 cm thick. Pups measure 62 to 68 cm in length (nose-tail) and weigh 6.4 to 7.9 kg at birth, males tending to be heavier than females. Adult females range in length from 132 to 181 cm and weigh between 61 and 105 kg (for a pregnant specimen); males measure up to 200 cm in length and attain weights well in excess of 200 kg.

II. Distribution and Abundance

There are only 9300 to 11,700 Australian sea lions occupying dieir wide geographic range in more than 50 scattered colonies, of which only 5 produce more than 100 pups in a breeding season. Three-quarters of the population resides in South Australia and a quarter occurs in Western Australia, where more than half the breeding colonies are located, all of which are small. The largest breeding colonies are on Purdie Island (32°S,133°E), Dangerous Reef (350S,135°E), Seal Bay (36°S.137°E) on Kangaroo Island and die two islands of The Pages. Australian sea lions once ranged as far as die eastern end of Bass Strait, but today only stragglers occur there and beyond. They were hunted during die sealing era from die late 18th to the mid-19di century for their skins and oil. when only a few diousand skins are reported to have been harvested. It is not possible to estimate the number killed for oil, because “seal oil” included fur seal oil as well in die cargoes. However, diere may not have been many sea lions to be taken anyway compared with die large fur seal populations, which are increasing today after having been almost exterminated by early sealers. However, because die first complete census over the sea lion’s en tire breeding range has been carried out only recently, it cannot be determined at this stage whether numbers are increasing or decreasing. Future surveys of all breeding colonies will need to be undertaken, as counts of live and dead pups provide the most accurate estimates of the size of the total population.

Figure 1 Neophoca cinerea, adult male (note white “cap” on head), three adult females, and juvenile (circa 18 months) resting on center female at Seal Bay, Kangaroo Island, Smith Australia. Photo by John K. Ling.

III. Life History

The life history of Neophoca is unique in a number of aspects: the approximately 17.5-month reproductive cycle, a protracted (i.e., 5-month) pupping season, and prolonged gestation and lactation until the next pup is born. This life history is likely to be an adaptation to the sea lion s environment, which is characterized as a low-energy, stable milieu associated with the eastward flowing Leeuwin Current.

Pups are born a few days after the females have moved to their breeding sites, to which they are known to return for successive birthings. Viable twins have never been observed, but two aborted fetuses, believed to be twins and estimated to be about 3 months postimplantation, were found on Kangaroo Island in 1985.

Mating takes place 7 to 10 days postpartum; there is a 3-to 4-month-free blastocyst (embryonic diapause) stage, followed by a gestation period up to 14 months in duration. The pup is suckled for the next 15-18 months and during this time it learns to forage for food that it will consume in later life. The milk is low in energy (fat) compared with other pinnipeds and its quality may vary according to the foraging success of the mother and stage of lactation. After they are weaned, sea lions feed on cephalapods, crustaceans, and fish. It is not known how far offshore they forage, but diving appears to begin as soon as females leave the rookery and continues to mean depths of 92 m for up to 8 min per dive over the continental shelf. This is a longer duration than dives of most other otariids (eared seals). Prey is generally seized in the mouth and shaken violently at the surface to remove cuttle bones, skin, or skeletons before swallowing. Depending on size, experimental markers take from 5 to 48 hr to pass through the alimentary tract. Australian sea lions are infected by the usual array of external and internal parasites: lice and mites, and acanthocephala, nematodes, cestodes, and trematodes. Dissections often reveal very heavy infestations.

While the pelage is unlikely to be involved in thermoregulation, the flattened hairs overlap each other and provide a smooth but flexible outer surface that reduces turbulence when swimming. Periodic renewal of the hair coat ensures that it functions efficiently in whatever role it has. The timing of pelage renewal or molt is variable. Immature sea lions molt during the breeding season, females begin their molt about 4 months after parturition, and adult males do not start their molt until about 9 months after breeding occurs.

The Australian sea lion’s unusual life history enables it to survive as a very small population scattered over a wide, nutrient-poor longitudinal range. The longer than normal (pinniped) gestation and lactation periods allow the female to nurture a developing fetus and growing pup while having to forage for scarce food resources. Normal growth rates can also be achieved despite the low-energy content of the milk. At the same time, the long maternal association confers many learning and protective advantages on the young sea lion. The protracted, asynchronous pupping season spread out over a wide geographic area again means that food resources can be better shared and there is not a sudden influx of newly independent sea lions, such as occurs with more highly synchronized species that occupy nutrient-rich, higher latitudes.

Figure 2 Present and past distribution of Neophoca cinerea. Unbroken solid line depicts current knoivn breeding range, broken solid line depicts extent of seasonal stragglers, and broken open line depicts extent of former breeding range.

IV. Behavior

The protracted pupping season, during which mating is effected, ensures that there is a high turnover of territories and a breakdown of any harem system. In contrast to many otariids in which dominant males control small to large numbers of females, Neophoca practices what is known as sequential polygyny, which still allows males access to several females in a season, but one at a time. Nevertheless, aggressive encounters do take place between rival breeding males and are a significant cause of mortality among young pups that are unfortunate enough to be attacked or trampled by rampaging bulls. Their lumbering gait resembles something of an ungainly gallop a little above a fast human walking pace and punctuated by frequent rests.

Females are most solicitous of their young, and several tourist visitors to Seal Bay and other breeding colonies have received nasty bites when they approached too close to a cow with her pup. When returning from a foraging trip, a female will call from the sea with a soft “moo” and wait for her pup’s answering call, which resembles a lamb’s bleat. Site fidelity is veiy strong, so little searching for each other is necessary. Once the two are reunited, recognition is confirmed by smelling.

Sea lions are powerful and skillful swimmers, using their large front flippers to propel them rapidly through the water. They are also excellent surfers and can often be seen riding the waves right into the shallows or “porpoising” along wave crests and troughs further out to sea.

Large males tend to lie apart from other sea lions, but females and immature animals often lie close together wriggling. squirming, and scratching constantly. On hot days when the sun temperature may exceed 45°C they will occasionally go into the sea and return a short while later to allow evaporative cooling to take effect. Sea lions may also venture some distance inland to lie under bushes or up steep slopes to find a shelter: they are quite agile on land.

V. Conservation and Management

The Australian sea lion colony at Seal Bay on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, is internationally famous because of its proximity to a large city (Adelaide) and the public being able to view the animals at close quarters. In view of the near-threatened (IUCN) status of this species and its importance to the tourist industry on Kangaroo Island (no other colonies are so easily accessible), the South Australian government has embarked on an intensive management strategy.

The whole Seal Bay area has been designated a conservation park. Public access is limited to the main beach and only in the company of authorized personnel, but there are also viewing platforms overlooking the beach and other restricted areas. The main pupping sites in coves to the west of Seal Bay have been declared prohibited areas. Regular classified censuses are conducted to monitor the status of the Seal Bay colony and enhance its chances of survival and value to tourism.

However, many odier Australian sea lion colonies appear to be suffering very high pup mortality (30-40%) and decreasing pup production. Only widi a widespread and cooperative research and management effort will the species be perhaps more secure.