I. Distribution

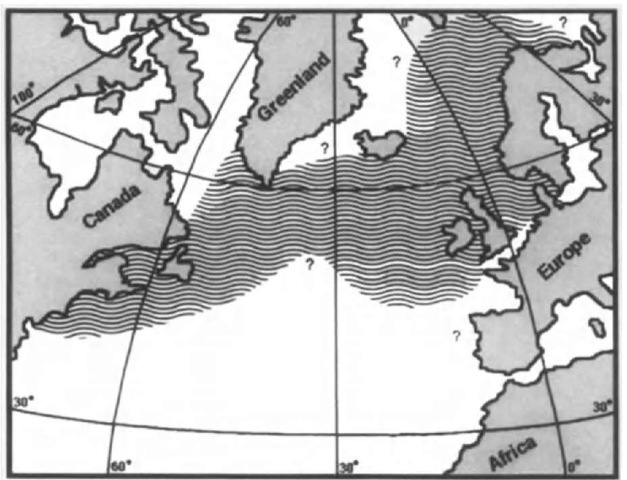

Inhabitants of the cold-temperate North Atlantic, Atlantic white-sided dolphins are usually encountered in waters over the continental shelf and slope, extending into deeper oceanic waters and occasionally into coastal areas (Fig. 1). The southern limit of this species in the western Atlantic is Cape Cod and the submarine canyons south of Georges Bank, and Brittany in the east. Groups of Atlantic white sides are often seen by fishermen and deep-water sailors off the coasts of New England, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland, the western British Isles, northern Europe, and in the Norwegian Sea. There are no records of this species from the inner Baltic Sea, although some sightings and strandings are known from the straits between Denmark, Norway, and western Sweden. The northern distribution limits are poorly known but extend at least to southern Greenland, southern Iceland, and the south coast of Svalbard Island.

Figure 1 Known distribution limits of the Atlantic white-sided dolphin. The patterned area indicates areas of regular occurrence and question marks indicate uncertainty about occurrence in particidar areas.

II. Appearance and Life History

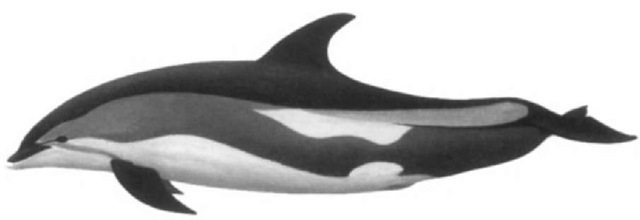

Atlantic white-sided dolphins are robust and powerful, impressively patterned, and more colorful than most dolphins. A narrow, bright white patch on the side extends back from below the dorsal fin and continues toward the flukes as a yellow-brown blaze above a thin dark stripe (Fig. 2). The back and dorsal fin are black or very dark gray, as are the flippers and flukes, whereas the belly and lower jaw are white, and the sides of the body a lighter gray. A black eye ring extends in a thin line to the upper jaw, and a very thin stripe extends backward from the eye ring to the external ear. A faint gray stripe may connect the leading edge of the flipper with the rear margin of the lower jaw. The beak is short and grades smoothly into the “melon” (forehead). The upper jaw contains 29-40 and the lower jaw 31-38 small, conical teeth.

Male Atlantic white-sided dolphins are known to reach a maximum body length about 270 cm and a weight of 230 kg, whereas adult females reach a maximum size about 20 cm shorter and 50 kg lighter. This is smaller than that well-known oceanarium inhabitant, the bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops trun-catus (around 380 cm/270 kg maximum), and a bit longer and a lot heavier than the short-beaked common dolphin, DeJphi-nus delphis (around 230 cin/75 kg). Females reach sexual maturity at 200-220 cm, at ages from 6 to 12 years. Males reach sexual maturity at lengths of 215-230 cm, corresponding to ages of 7-11 years. Maximum ages recorded were 22 and 27 years for males and females, respectively. At birth, Atlantic white-sided dolphins are around 120 cm long, after an approximately 11-month gestation period, and weigh about 25 kg. In the western Atlantic, the calving season peaks in midsummer, whereas in the eastern Atlantic the calving season may extend several months longer. The lactation period lasts around 18 months, and some stranded individuals were observed to be both pregnant and lactating, suggesting that some individuals may breed annually.

III. Group Size, Behavior, and Ecology

The number of Atlantic white-sided dolphins observed in a group ranges from a few individuals to several hundred, and mean group size appears to vary with location. In Newfoundland inshore waters, 50-60 dolphins in a group are typical; in inshore waters of the British Isles and near Iceland, groups usually contain less than 10 individuals; off the New England coast, group size ranges from a few to around 500, but the usual group size is around 40. Some segregation by sex and age has been suggested from mass stranding records—larger juveniles are absent from some mass-stranded groups that contain many calves, adult males, and pregnant females.

Analysis of the stomach contents of mass-stranded, incidentally entangled, and drive-caught dolphins is used to assess their diet, as diagnostic “hard parts” (crustacean shells, fish ear bones, and squid beaks) accumulate in stomach chambers. A general indication of the importance of particular prey items can be inferred from the percentage contribution of each type, although the number of meals represented by such traces is usually unknown and there may be bias in the retention of different types. Major prey species of Atlantic white-sided dolphins include herring, small mackeral, gadid fishes (codfish and their relatives), smelts and hake, sand lances, and several types of squid. Different prey species may predominate at different times of year, representing seasonal movements of prey, or in different areas, indicating prey and habitat variability in the environment. For example, different species of squid are eaten by these dolphins on opposite sides of the Atlantic, whereas in spring and autumn, sand lance and dolphin distributions in the Gulf of Maine appear to mirror each other. Atlantic white-sided dolphins are probably not deep divers—the maximum dive time recorded from a tagged dolphin was 4 min and most dives were less than a minute in duration.

IV. Abundance and Human Impacts

Censusing oceanic dolphins is a difficult task, requiring extensive aerial surveys or long observation tracks from survey ships (or both) and then extrapolation of the densities observed to immense ocean areas. Given the wide distribution of At lantic white-sided dolphins across the northern reaches of the Atlantic, rather wide confidence limits on abundance estimates are to be expected. Estimates for the western Atlantic total about 40,000 animals, and for the entire Atlantic a few hundred thousand. This species is not currently hunted on a large scale anywhere throughout its range, although historically many were killed in drive fisheries in Norway and Newfoundland, and smaller numbers taken off Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Incidental mortality has been documented in many areas and these dolphins may be particularly susceptible to entanglement in midwater trawl nets, including some recent large catches in pelagic trawl nets in the Atlantic Frontier off Ireland.

Figure 2 Color pattern of the Atlantic white-sided dolphin.

V. Evolutionary Relationships

Molecular analysis has been used to examine the evolutionary relationships of Lagenorhynclius acutus and other dolphins, including the five other currently recognized members of the genus Lagenorhynchus. Although formal taxonomic revision awaits a more comprehensive review of morphological and molecular characters, molecular evidence suggests that L. acutus is not closely related to other putative members of Lagenorhynchus and should be recognized in a separate genus.