Life Cycle

After the roots of the primary dentition are completed at about age 3, several of the primary teeth are in use only for a relatively short period. Some of the primary teeth are found to be missing at age 4, and by age 6, as many as 19% may be missing.1 By age 10, only about 26% may be present. The second molars in both arches and the maxillary incisors appear to be the most unstable of the primary teeth. Even so, the developing and completed primary dentition serves a number of purposes during that time and the period of transition to the permanent dentition.

Importance of Primary Teeth

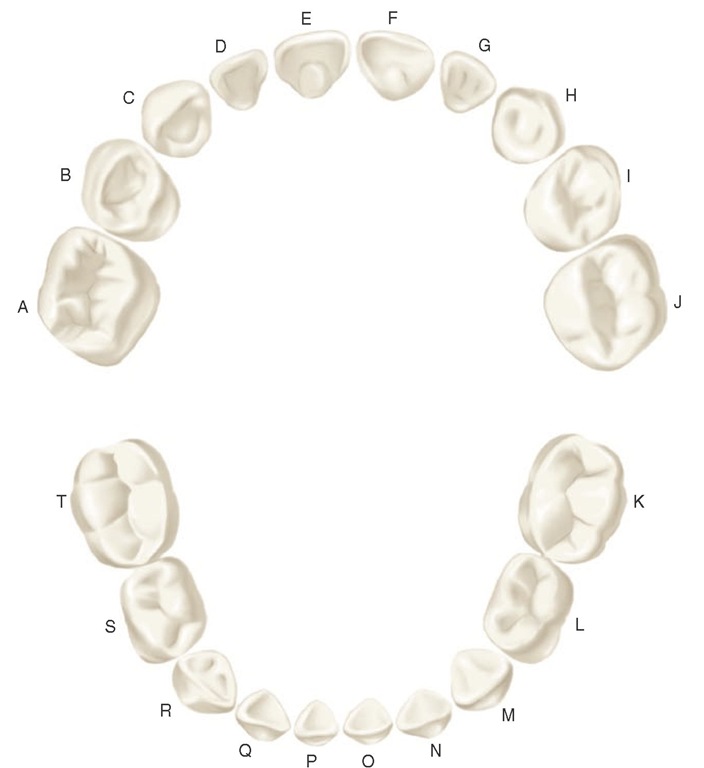

The general order of eruption of the primary dentition is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 3-1: central incisor, lateral incisor, first molar, canine, and second molar, with the mandibular pairs preceding the maxillary teeth.2,3 The loss of the deciduous teeth tends to mirror the eruption sequence: incisors, first molars, canines, and second molars, with the mandibular pairs preceding the maxillary teeth.

The high peak for caries attack occurs at age 13, when only 5% of the primary teeth remain. The susceptibility to dental caries is a function of exposure time to the oral environment and morphological type. The increase in prevalence of dental caries among tooth types is the reverse of their order of eruption. However, the relative susceptibility of different tooth surfaces is a complex problem. Although dental caries of the primary dentition and loss of these teeth are sometimes thought of erroneously as only an annoyance, this belief fails to acknowledge the role of the primary teeth in mastication and their function in maintaining the space for eruption of the permanent teeth.

The development of adequate spacing (Figure 3-2) is an important factor in the development of normal occlusal relations in the permanent dentition. Thus there should be no question of the importance of preventing and treating dental decay and providing the child with a comfortable functional occlusion of the deciduous teeth. Therefore in this topic the primary teeth are described in advance of the permanent dentition so that they may be given their proper sequence in the study of dental anatomy and physiology.

Nomenclature

The process of exfoliation of the primary teeth takes place between the seventh and the twelfth years. This does not, however, indicate the period at which the root resorption of the deciduous tooth begins. It is only 1 or 2 years after the root is completely formed and the apical foramen is established that resorption begins at the apical extremity and continues in the direction of the crown until resorption of the entire root has taken place and the crown is lost from lack of support.

Figure 3-1 Diagrammatic representation of the chronology of the primary teeth. Eruption is completed at the approximate time indicated by the dotted area on the roots of the teeth. iu, Intrauterine.

Figure 3-2 Primary dentition in a child 5 years of age.

The primary teeth number 20 total—10 in each jaw—and they are classified as follows: four incisors, two canines, and four molars in each jaw.Beginning with the median line, the teeth are named in each jaw on each side of the mouth as follows: central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, first molar, and second molar.

The primary teeth have been called temporary, milk, or baby teeth. These terms are improper because they foster the implication that these teeth are useful for a short period only. It is emphasized again that they are needed for many years of growth and physical development. Premature loss of primary teeth because of dental caries is preventable and is to be avoided.

The first permanent molar, commonly called the 6-year molar, makes its appearance in the mouth before any of the primary teeth are lost. It comes in immediately distal to the primary second molar (see Figure 2-10).

The primary dentition is complete at about 2.5 years of age, and no obvious intraoral changes in the dentition occur (Figures 3-4 and 3-5) until the eruption of the first permanent molar. The position of the incisors is usually relatively upright with spacing often between them. Attrition occurs, and a pattern of wear may be present.

The primary molars are replaced by permanent premolars. No premolars are present in the primary set, and no teeth in the deciduous set resemble the permanent premolar. However, the crowns of the primary maxillary first molars resemble the crowns of the permanent premolars as much as they do any of the permanent molars. Nevertheless, they have three well-defined roots, as do maxillary first permanent molars. The deciduous mandibular first molar is unique in that it has a crown form unlike that of any permanent tooth (see Figure 3-24, C). It does, however, have two strong roots, one mesial and one distal—an arrangement similar to that of a mandibular permanent molar. These two primary teeth, the maxillary and mandibular first molars, differ from any teeth in the permanent set when crown forms are compared, in particular (see Figures 3-21 and 3-24). The primary first molars, maxillary and mandibular, are described in detail later in this topic.

FIGURE 3-3 Universal numbering system for primary dentition.

Major Contrasts between Primary and Permanent Teeth

In comparison with their counterparts in the permanent dentition, the primary teeth are smaller in overall size and crown dimensions. They have markedly more prominent cervical ridges, are narrower at their "necks," are lighter in color, and have roots that are more widely flared; in addition, the buccolingual diameter of primary molar teeth is less than that of permanent teeth.4 More specifically, in comparison with permanent teeth, the following differences are noted:

1. The crowns of primary anterior teeth are wider mesiodistally in comparison with their crown length than are the permanent teeth.

2. The roots of primary anterior teeth are narrower and longer comparatively. Narrow roots with wide crowns present an arrangement at the cervical third of crown and root that differs markedly from that of the permanent anterior teeth.

3. The roots of the primary molars accordingly are longer and more slender and flare more, extending out beyond projected outlines of the crowns. This flare allows more room between the roots for the development of permanent tooth crowns (see Figures 3-21 and 3-22).

4. The cervical ridges of enamel of the anterior teeth are more prominent. These bulges must be considered seriously when they are involved in any operative procedure (see Figure 3-13).

5. The crowns and roots of primary molars at their cervical portions are more slender mesiodistally.

6. The cervical ridges buccally on the primary molars are much more pronounced, especially on the maxillary and mandibular first molars (see Figures 3-25 through 3-28).

7. The buccal and lingual surfaces of primary molars are flatter above the cervical curvatures than those of permanent molars, which narrows the occlusal surfaces.

8. The primary teeth are usually less pigmented and are whiter in appearance than the permanent teeth.

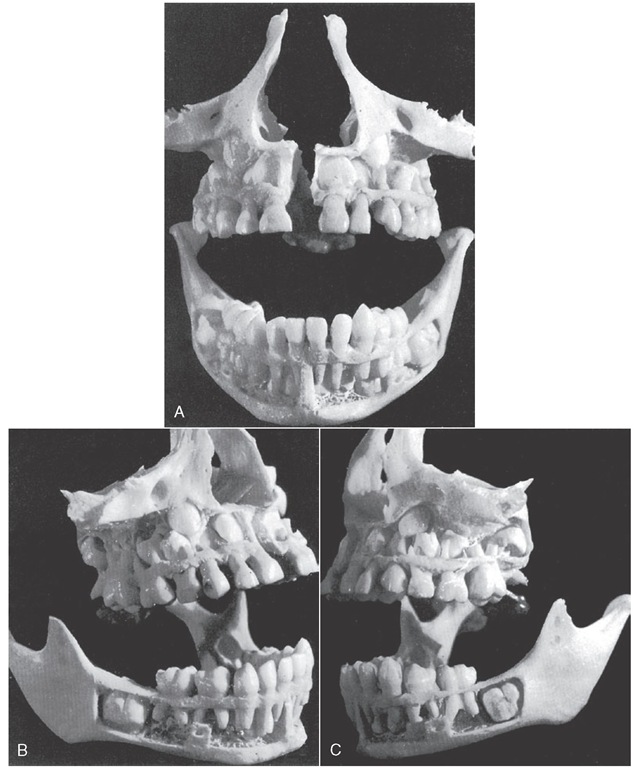

Figure 3-4 A, This is a specimen of a 5- to 6-year-old child prepared to show a full complement of primary teeth, the beginning of resorption of deciduous roots in some, and no apparent resorption in others. This front view shows the relative positions of the developing crowns of the permanent anterior teeth. The maxillary central and lateral incisors and the canine are shown overlapped in a narrow space, waiting for future development of the maxilla that will allow them to develop roots and improve the alignment. B, Right side. Unless they were lost in preparation, no development shows of mandibular permanent premolars. The tiny cusps formed at this age would be lost easily in preparation. C, Left side. Note the crowns of permanent maxillary premolars located between the roots of the first and second primary molars, with their roots still intact. Note the well-developed first permanent maxillary molar entirely erupted with half its roots formed. Ordinarily, the mandibular first permanent molar comes in and takes its place first, the maxillary molar following. The specimen shows the mandibular molar still covered with bone and no roots in evidence. The maxillary second molar crown is well developed and located in a place that is about level with the present root development of the permanent maxillary first molar.

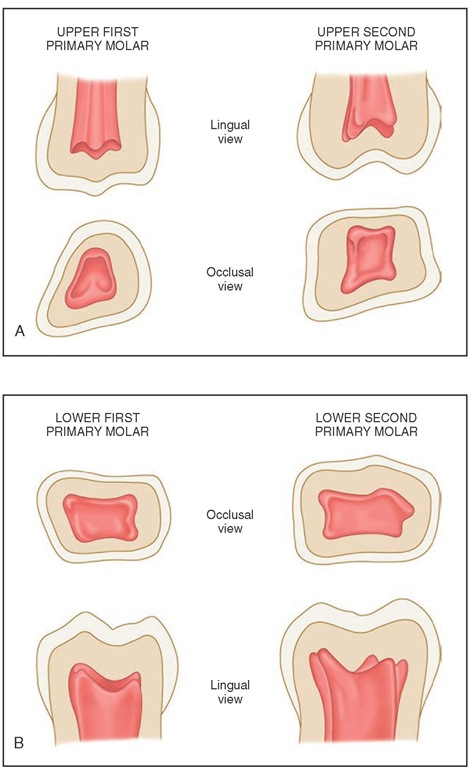

Pulp Chambers and Pulp Canals

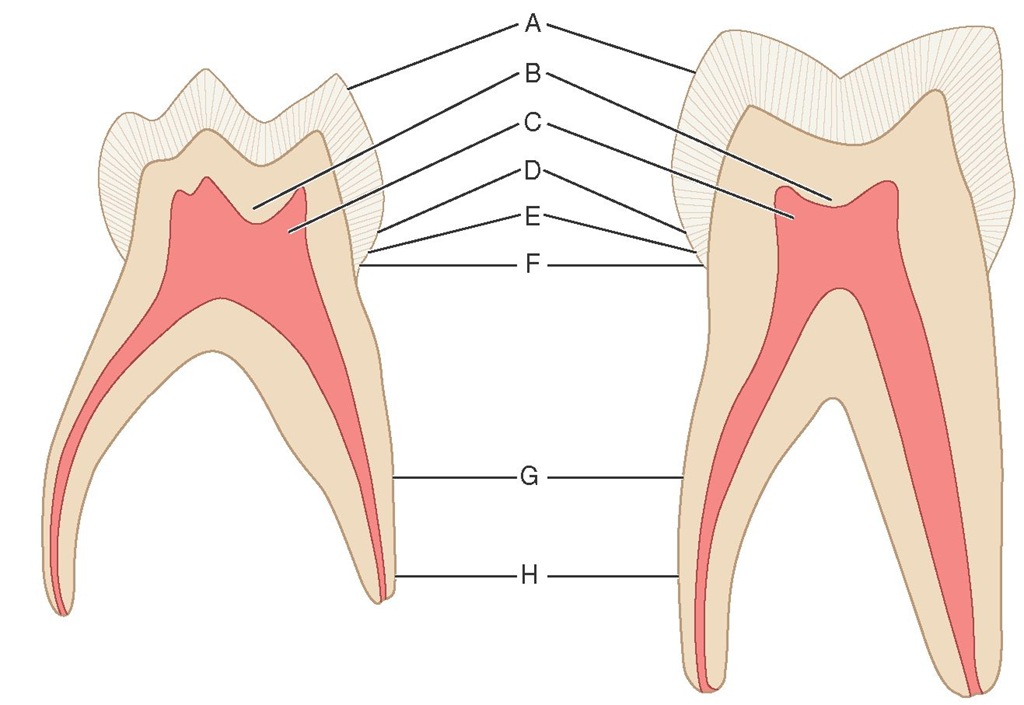

A comparison of sections of primary and permanent teeth demonstrates the shape and relative size of pulp chambers and canals (Figure 3-6), which is noted here:

1. Crown widths in all directions are large in comparison with root trunks and cervices.

2. The enamel is relatively thin and has a consistent depth.

3. The dentin thickness between the pulp chambers and the enamel is limited, particularly in some areas (lower second primary molar).

4. The pulp horns are high, and the pulp chambers are large (Figure 3-7, A and B).

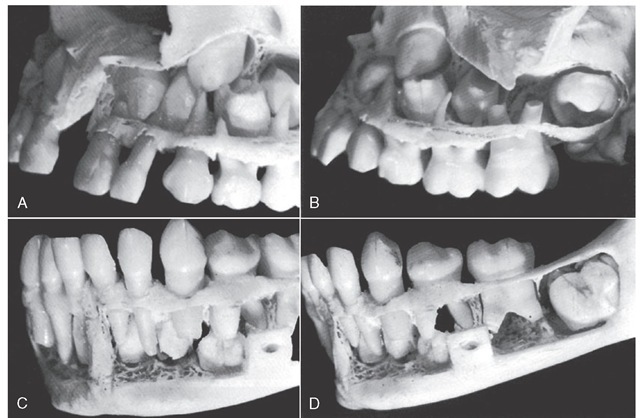

5. Primary roots are narrow and long when compared with crown width and length.

Figure 3-5 A sectional close-up of the specimen in Figure 3-4. A, The left side of the maxilla. The developing crowns of the central and lateral incisors, the canine, and two premolars are clearly in view. B, The left side of the maxilla, posteriorly. The molar relationship, both deciduous and permanent, is accented here. C, This is a good view of the mandible anteriorly and to the left. Permanent central and lateral incisors and the canine may be seen. Notice that the permanent canine develops distally to the primary canine root. D, Posteriorly, examination of the specimen mandible fails to find crown development of permanent premolars. However, the hollow spaces showing between the roots of primary molars may indicate a loss of material during the difficult process of dissection. The first permanent molar has progressed in crown formation, but the maturation of the whole tooth with alignment is far behind its opposition in the maxilla above it (see Figure 3-4, C).

Figure 3-6 Comparison of maxillary, primary, and permanent second molars, linguobuccal cross section. A, The enamel cap of primary molars is thinner and has a more consistent depth. B, A comparatively greater thickness of dentin is over the pulpal wall at the occlusal fossa of primary molars. C, The pulpal horns are higher in primary molars, especially the mesial horns, and pulp chambers are proportionately larger. D, The cervical ridges are more pronounced, especially on the buccal aspect of the first primary molars. E, The enamel rods at the cervix slope occlusally instead of gingivally as in the permanent teeth. F, The primary molars have a markedly constricted neck compared with the permanent molars. G, The roots of the primary teeth are longer and more slender in comparison with crown size than those of the permanent teeth. H, The roots of the primary molars flare out nearer the cervix than do those of the permanent teeth.

Figure 3-7 A and B, Pulp chambers in the primary molars. Note the contours of the pulp horns within them.

6. Molar roots of primary teeth flare markedly and thin out rapidly as the apices are approached.

Studying the comparisons between the deciduous and the permanent dentitions (Figures 3-8 and 3-9) is of utmost importance. Discussion of further variations between the macroscopic form of the deciduous and the permanent teeth follows, with a detailed description of each deciduous tooth.