Interproximal Spaces (Formed by Proximal Surfaces in Contact)

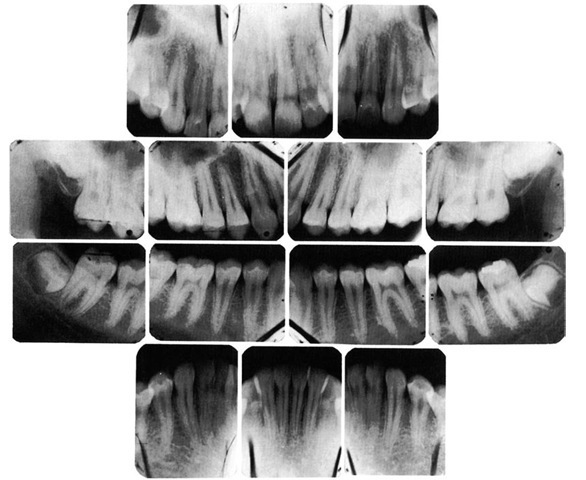

The interproximal spaces between the teeth are triangularly shaped spaces normally filled by gingival tissue (gingival papillae). The base of the triangle is the alveolar process, the sides of the triangle are the proximal surfaces of the contacting teeth, and the apex of the triangle is in the area of contact. The form of the interproximal space will vary with the form of the teeth in contact and will depend also on the relative position of the contact areas (Figures 5-12 through 5-14). Normally, a separation of 1 to 1.5 mm exists between the enamel and alveolar bone. Thus the distance from the CEJ (cervical line) to the crest of the alveolar bone as seen radiographically (see Figure 5-9) is 1 to 1.5 mm in a normal occlusion in the absence of disease.

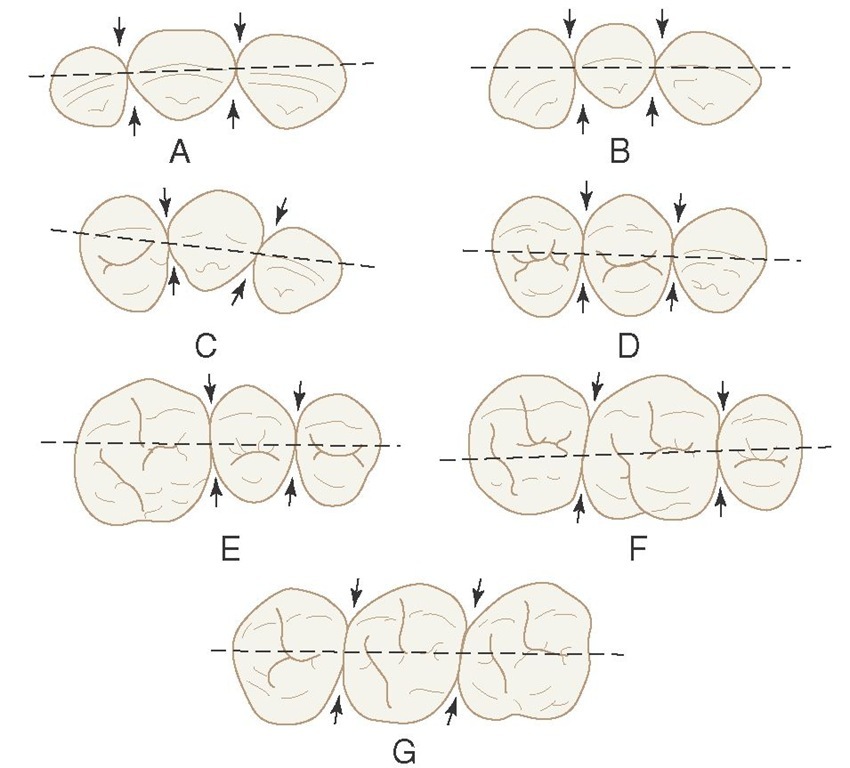

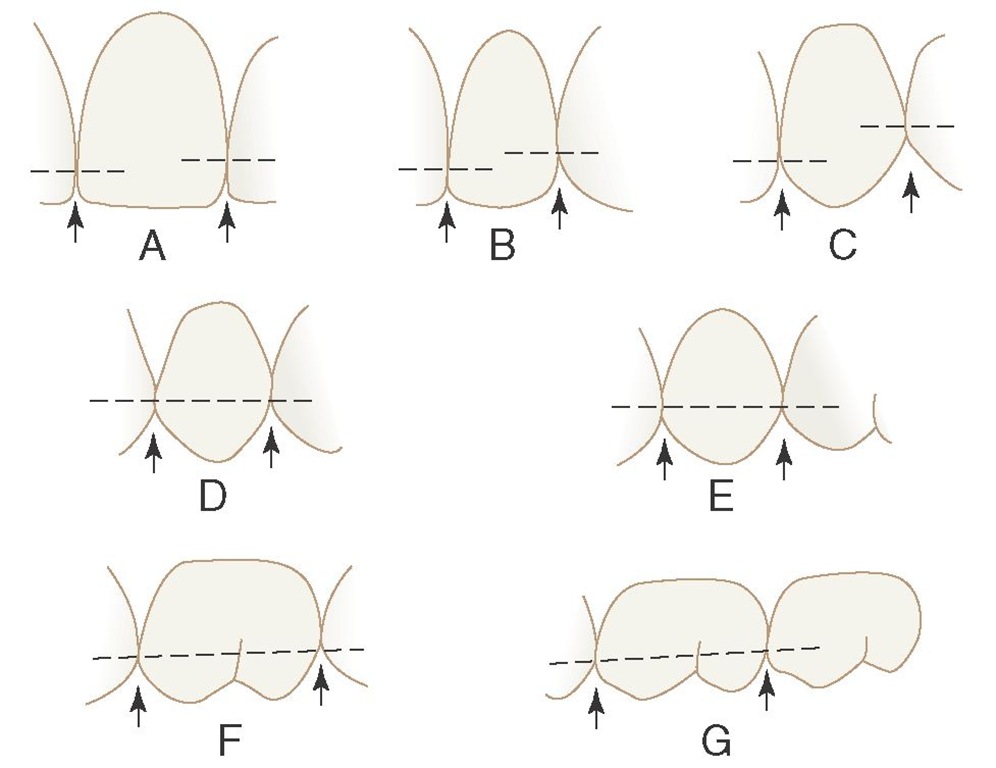

Figure 5-8 Outline drawings of the maxillary teeth from the incisal and occlusal aspects with broken lines bisecting the contact areas. These illustrations show the relative positions of the contact areas labiolingually and buccolingually. Arrows point to embrasure spaces. A, Central incisors and lateral incisor. B, Central and lateral incisors and canine. C, Lateral incisor, canine, and first premolar. D, Canine, first premolar, and second premolar. E, First molar, second premolar, and first molar. F, Second premolar, first molar, and second molar. G, First, second, and third molars.

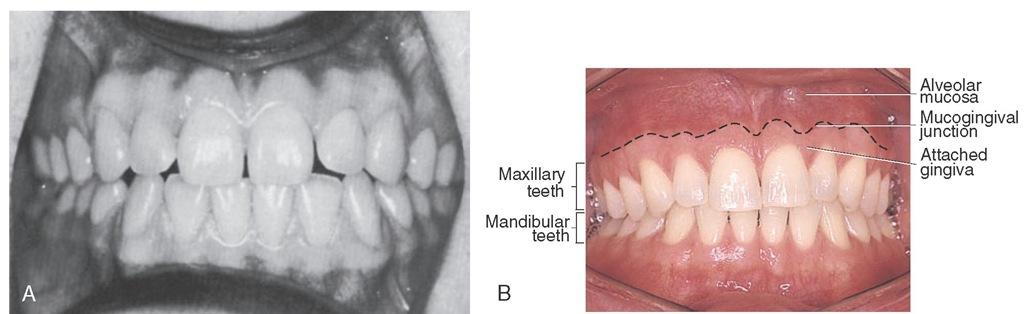

Proper contact and alignment of adjoining teeth allows proper spacing between them for the normal bulk of gingival tissue attached to the bone and teeth. This gingival tissue is a continuation of the gingiva covering all of the alveolar process. The surface keratinization of the gingiva and the density and elasticity of the gingival tissues help maintain these tissues against trauma during mastication and invasion by bacteria.

Because the teeth are narrower at the cervix mesiodistally than they are toward the occlusal surfaces and the outline of the root continues to taper from that point to the apices of the roots, considerable spacing is created between the roots of one tooth and the roots of adjoining teeth. This arrangement allows sufficient bone tissue between one tooth and another, which anchors the teeth securely in the jaws.

Figure 5-9 Radiograph demonstrating form of alveolar crest, contact areas, and relation to form of the crown.

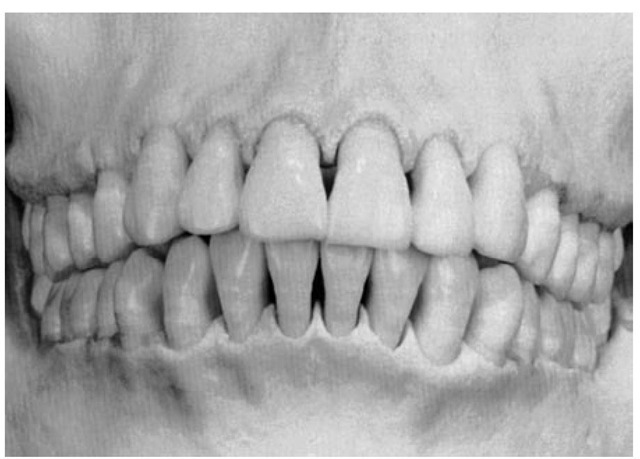

Figure 5-10 Contact relations in a patient with "normal" occlusion. A, Maxillary arch. B, Mandibular arch.

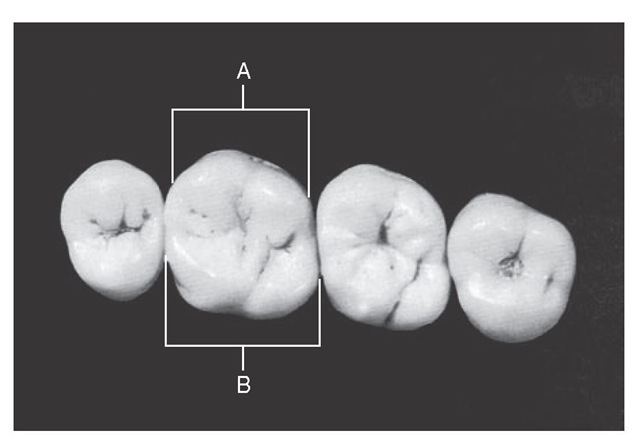

Figure 5-11 Broad contact areas of the mandibular first and second molars in a young adult, 21 years old.

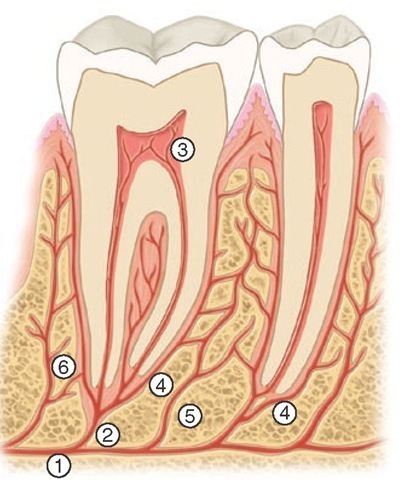

It also simplifies the problem of space for the blood and nerve supply to the surrounding alveolar process and other investing tissues of the teeth (see Figure 5-12).

The type of tooth also has a bearing on the interproximal space. Some individuals have teeth that are wide at the cervices, constricting the space at the base. Others have teeth that are more slender at the cervices than usual; this type of tooth widens the space. Teeth that are oversize or unusually small will likewise affect the interproximal spacing. Never-theless, this spacing conforms to a plan that is fairly uniform, provided that the anatomical form is normal and the teeth are in good alignment.

Figure 5-12 Schematic drawing of distribution of the periodontal blood vessels and interdental papillae. 1, Inferior alveolar artery; 2, dental arteriole; 3, pulpal branches; 4, periodontal ligament arteriole; 5 and 6, interalveolar arterioles.

Embrasures (Spillways)

When two teeth in the same arch are in contact, their curvatures adjacent to the contact areas form spillway spaces called embrasures. The spaces that widen out from the area of contact labially or buccally and lingually are called labial or buccal and lingual interproximal embrasures. These embrasures are continuous with the interproximal spaces between the teeth (see Figure 5-10). Above the contact areas incisally and occlusally, the spaces, which are bounded by the marginal ridges as they join the cusps and incisal ridges, are called the incisal or occlusal embrasures. These embrasures, and the labial or buccal and lingual embrasures, are continuous (Figure 5-15; see also Figure 5-8). The curved proximal surfaces of the contacting teeth roll away from the contact area at all points, occlusally, labially or buccally, and lin-gually and cervically, and the embrasures and interproximal spaces are continuous, as they surround the areas of contact.

The form of embrasures serves two purposes: (1) it provides a spillway for food during mastication, a physiological form that reduces the forces brought to bear on the teeth during the reduction of any material that offers resistance; and (2) it prevents food from being forced through the contact area. When teeth wear down to the contact area so that no embrasure remains, especially in the incisors, food is pushed into the contact area even when teeth are not mobile.

The design of contact areas, interproximal spaces, and embrasures varies with the form and alignment of the various teeth; each section of the two arches shows similarity of form. In other words, the contact form, the inter-proximal spacing, and the embrasure form seem rather constant in sectional areas of the dental arches. These sections are named as follows: the maxillary anterior section, the mandibular anterior section, the maxillary posterior section, and the mandibular posterior section. All embrasure spaces are reflections of the form of the teeth involved. Maxillary central and lateral incisors exhibit one embrasure form, the mandibular incisors another, and so on.

Figure 5-13 The form of the gingiva is related to the form of the teeth, contact areas, spacing between the teeth, and effects of periodontal disease and dental caries. A, Interdental papillae do not fill the interproximal areas in several places because of spacing between the teeth. B, Clinically normal gingivae; the form is different because of the form of the teeth, including contact areas.

Figure 5-14 The form of the teeth, position and wear of contact areas, type of teeth, and level of eruption of the teeth determine the form of the interproximal "spaces." These factors also determine the interproximal shape of the crest of alveolar bone.

FIGURE 5-15 Outline drawings of the maxillary teeth in contact, with dotted lines bisecting the contact areas at the various levels as found normally. Arrows point to embrasure spaces. A, Central and lateral incisors. B, Central and lateral incisors and canine. C, Lateral incisor, canine, and first premolar. D, Canine and first and second premolars. E, First and second premolars and first molar. F, Second premolar, first molar, and second molar. G, First, second, and third molars.

Figure 5-16 Calibration of maxillary first molar. A, Calibration at prominent buccal line angles that functions by deflecting food material during mastication. B, Calibration of lingual contour from contact area mesially to contact area distally. There are no prominent line angles, but the development of the mesiolingual cusp has widened the rounded lingual form. Thus the two lingual embrasures are kept similar in size, even though the tooth makes contact with two teeth that are dissimilar lingually. This way, the lingual gingival tissue interproximally is properly protected by the equalization of lingual embrasures.

Maxillary posteriors and mandibular posteriors apparently require an embrasure design geared for their sections. In some cases, the constancy has to be attained by a tooth form adaptation (Figure 5-16). The canines, for instance, are shaped so that they act as a catalyst in these matters between anterior and posterior teeth. A line bisecting the labial portion of either canine seems to create an anterior half mesially that resembles half of an anterior tooth and a posterior half that resembles a posterior tooth. The mesial contact is at one level for contact with the lateral incisor, but the distal contact form must be at a level consistent with the contact form of the first premolar, whether maxillary or mandibular (see Figure 5-15, C).

Contact Areas and Incisal and Occlusal Embrasures from the Labial and Buccal Aspect

It is advisable to refer continually to the illustrations of contacts and embrasures during the reading of the descriptions that follow. Locate the illustration of interest (see Figure 5-15, A) while reading the details concerning contact area levels in the following paragraphs.