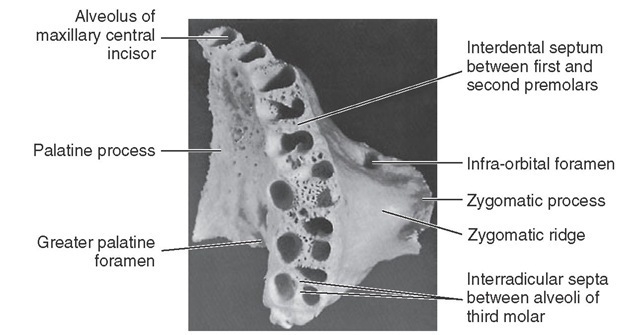

Palatine Process

The palatine process (Figures 14-2 through 14-8) is a horizontal ledge extending medially from the nasal surface of the maxilla. Its superior surface forms a major portion of the nasal floor. The inferior surfaces of the combined left and right palatine processes form the hard palate as far posteriorly as the second molar, where they articulate with the horizontal parts of the palatine bone (Figures 14-7 and 14-8) at the transverse palatine suture.

The inferior surface of the palatine process is rough and pitted for the palatine mucous glands in the roof of the mouth and is pierced by numerous small foramina for the passage of blood vessels and nerve fibers. At the posterior border of the process is a groove or canal that passes the greater palatine nerve and vessels to the palatal soft tissues. The posterior edge of the palatine process becomes relatively thin where it joins the palatine bone at the point of the greater palatine foramen. The palatine process becomes progressively thicker anteriorly from the posterior border. Anteriorly, the palatal process is confluent with the alveolar process surrounding the roots of the anterior teeth.

Immediately posterior to the central incisor alveolus, when looking at the medial aspect of the maxilla, one sees a smooth groove that is half of the incisive canal, when the two maxillae are joined together. The incisive fossa into which the canals open may be seen immediately lingual to the central incisors at the median line, or intermaxillary suture where the maxillae are joined. Two canals open laterally into the incisive foramen, the foramina of Stenson, carrying the nasopalatine nerves and vessels. Occasionally, two midline foramina are present, the foramina of Scarpi.

Extending laterally from the incisive foramen to the space between the lateral incisor and canine alveoli are the remnants of the suture between the maxilla and premaxilla. In most mammals the premaxilla remains an independent bone.

Figure 14-7 Palatine view of maxilla. Note the dental foramina in the deepest portion of the canine alveolus.

Figure 14-8 View of inferior surface of the maxilla showing alveolar process and alveoli.

ALVEOLAR PROCESS

The alveolar process makes up the inferior portion of the maxilla; it is that portion of the bone which surrounds the roots of the maxillary teeth and which gives them their osseous support. The process extends from the base of the tuberosity posterior to the last molar to the median line anteriorly, where it articulates with the same process of the opposite maxilla (see Figures 14-7 and 14-8). It merges with the palatine process medially and with the zygomatic process laterally (see Figure 14-8).

When one looks directly at the inferior aspect of the maxilla toward the alveoli with the teeth removed, it is apparent that the alveolar process is curved to conform with the dental arch. It completes, with its fellow of the opposite side, the alveolar arch supporting the roots of the teeth of the maxilla.

The process has a facial (labial and buccal) surface and a lingual surface with ridges corresponding to the surfaces of the roots of the teeth supported by it. It is made up of labi-obuccal and lingual plates of very dense but thin cortical bone separated by interdental septa of cancellous bone.

The facial plate is thin, and the positions of the alveoli are well marked on it by visible ridges as far posteriorly as the distobuccal root of the first molar (see Figure 14-2). The margins of these alveoli are frail, and their edges are sharp and thin. The buccal plate over the second and third molars, including the alveolar margins, is thicker. Generally, the lingual plate of the alveolar process is heavier than the facial plate. In addition, the alveolar process is longer where it surrounds the anterior teeth, sometimes extending posteriorly to include the premolars. In short, it extends farther down in covering the lingual portion of the roots.

The bone is very thick lingually over the deeper portions of the alveoli of the anterior teeth and premolars. The merging of the alveolar process with the palatal process brings about this formation. The lingual plate is paper thin over the lingual alveolus of the first molar, however, and rather thin over the lingual alveoli of the second and third molars. This thin lingual plate over the molar roots is part of the formation of the greater palatine canal (see Figure 14-8).

The alveolar process is maintained by the presence of the teeth. Should any tooth be lost, that portion of the alveolar process that supported the missing tooth will be subject to atrophic reduction. Should all of the teeth be lost, the alveolar process will eventually be virtually lost.

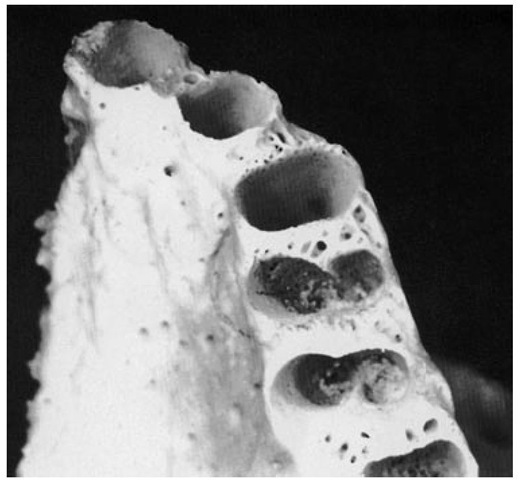

ALVEOLI (TOOTH SOCKETS)

The alveolar cavities are formed by the facial and lingual plates of the alveolar process and by connecting septa of bone placed between the two plates. The form and depth of each alveolus are determined by the form and length of the root it supports (see Table 1-1).

The alveolus nearest the median line is that of the central incisor (Figure 14-9; see also Figure 14-8). The periphery is regular and round, and the interior of the alveolus is evenly tapered and triangular in cross section, with the apex toward the lingual.

The second alveolus in line is that of the lateral incisor. It is generally conical and egg-shaped, or ovoid, with the widest portion to the labial. It is narrower mesiodistally than labiolingually and is smaller on cross section, although it is often deeper than the central alveolus. Sometimes, it is curved at the upper extremity (Figure 14-10; see also Figure 14-8).

The canine alveolus is the third from the median line. It is much larger and deeper than those just described. The periphery is oval and regular in outline, with the labial width greater than the lingual. The socket extends distally. It is flattened mesially and somewhat concave distally. The bone is so frail at the canine eminence on the facial surface of the alveolus that the root of the canine is often exposed on the labial surface near the middle third (see Figure 14-2).

The first premolar alveolus (see Figures 14-8 and 14-10) is kidney-shaped in cross section, with the cavity partially divided by a spine of bone that fits into the mesial developmental groove of the root of this tooth. This spine divides the cavity into a buccal and a lingual portion. If the tooth root is bifurcated for part of its length, as is often the case, the terminal portion of the cavity is separated into buccal and lingual alveoli. The socket is flattened distally and much wider buccolingually than mesiodistally (see Table 1-1).

Figure 14-9 Alveoli of the central incisor, lateral incisor, and canine.

Figure 14-10 Alveoli of the premolar area.

The second premolar alveolus is also kidney-shaped, but the curvatures are in reverse to those of the first premolar alveolus. The proportions and depth are almost the same. The septal spine is located on the distal side instead of the medial side, because the second premolar root is inclined to have a well-defined developmental groove distally. This tooth usually has one broad root with a blunt end, but it is occasionally bifurcated at the apical third.

The first molar alveolus (Figures 14-8 and 14-11) is made up of three distinct alveoli widely separated. The lingual alveolus is the largest; it is round, regular, and deep. The cavity extends in the direction of the hard palate, having a lingual plate over it that is very thin. The lingual periphery of this alveolus is extremely sharp and frail. This condition may contribute to the tissue recession often seen at this site.

The mesiobuccal and distobuccal alveoli of the first molar have no outstanding characteristics except that the buccal plates are thin. The bone is somewhat thicker at the peripheries than that found on the lingual alveolus. Nevertheless, it is thinner farther up on the buccal plate. It is not uncommon for one to find the roots uncovered by bone in spots when examining dry specimens.

Figure 14-11 Alveoli of the molar area. Note the thinness of the buccal plates over the first molar roots compared with those of the second and third maxillary molars. The third molar alveoli are rarely separated as distinctly as in this specimen. Figures 14-9, 14-10, and 14-11 demonstrate a number of significant points concerning the maxillary alveoli. In Figure 14-9 the facial cortical plate of bone is thin over the anterior teeth and is considerably thicker over the posterior teeth, especially the molars. Cancellous bone seems to exist buccal to some of the posterior roots. In Figure 14-10 interradicular septa are thick but with numerous nutrient canals. In Figure 14-11 cancellous bone, furnishing numerous opportunities for blood supply, is evident in the apical portions of the alveoli. The anterior alveoli are lined laterally with a layer of smooth cortical bone. This lining is less prominent in the posterior alveoli.

The forms of the buccal alveoli resemble the forms of the roots they support. The mesiobuccal alveolus is broad buc-colingually, with the mesial and distal walls flattened. The distobuccal alveolus is rounder and more conical.

The septa that separate the three alveoli (interradicular septa) are broad at the area that corresponds to the root bifurcation, and they become progressively thicker as the peripheries of the alveoli are approached. The bone septa are very cancellous, which denotes a rich blood supply, as is true of all the septa, including those separating the various teeth as well.

A general description of the alveoli of the second molar would coincide with that of the first molar; these alveoli are closer together, since the roots of this tooth do not spread as much. As a consequence, the septa separating the alveoli are not as heavy.

The third molar alveolus is similar to that of the second molar, except that it is somewhat smaller in all dimensions. Figure 14-11 shows a third molar socket to accommodate a tooth with three well-defined roots, a rare occurrence. Usually, the two buccal (and often all three) roots will be fused. The interradicular septum changes accordingly. If the roots of the tooth are fused, a septal spine will appear in the alveolus at the points of fusion on the roots marked by deep developmental grooves.

MAXILLARY SINUS

The maxillary sinus lies within the body of the bone and is of corresponding pyramidal form; the base is directed toward the nasal cavity. Its summit extends laterally into the root of the zygomatic process. It is closed in laterally and above by the thin walls that form the anterolateral, posterolateral, and orbital surfaces of the body. The sinus overlies the alveolar process in which the molar teeth are implanted, more particularly, the first and second molars, the alveoli of which are separated from the sinus by a thin layer of bone. Occasionally, the maxillary sinus will extend forward far enough to overlie the premolars also. It is not uncommon to find the bone covering the alveoli of some of the posterior teeth extending above the floor of the cavity of the maxillary sinus, forming small hillocks.

Regardless of the irregularity and the extension of the alveoli into the maxillary sinus, a layer of bone always separates the roots of the teeth and the floor of the sinus in the absence of pathological conditions. A layer of sinus mucosa is also always between the root tips and the sinus cavity.

MAXILLARY ARTICULATION

The maxilla articulates with the nasal, frontal, lacrimal, and ethmoid bones, above and laterally with the zygomatic bone, and occasionally with the sphenoid bone. Posteriorly and medially, it articulates with the palatal bone. Medially, it supports the inferior turbinate and the vomer and articulates with the opposite maxilla.

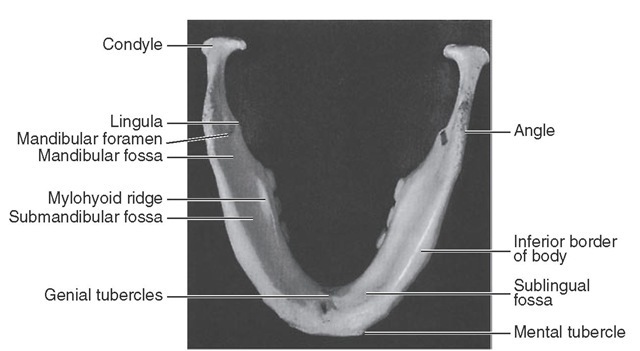

The Mandible

The mandible (Figures 14-12 through 14-23) is horseshoe-shaped and supports the teeth of the lower dental arch. This bone is movable and has no bony articulation with the skull. It is the heaviest and strongest bone of the head and serves as a framework for the floor of the mouth. It is situated immediately below the maxillary and zygomatic bone, and its condyles rest in the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone. This articulation is the temporomandibular joint.

The mandible has a horizontal portion, or body, and two vertical portions, or rami. The rami join the body at an obtuse angle.

The body consists of two lateral halves, which are joined at the median line shortly after birth. The line of fusion, usually marked by a slight ridge, is called the symphysis. The body of the mandible has two surfaces, one external and one internal, and two borders, one superior and one inferior.

To the right and left of the symphysis, near the lower border of the mandible, are two prominences called mental tubercles. A prominent triangular surface made by the symphysis and these two tubercles is called the mental protuberance (see Figure 14-16).

Figure 14-12 View of outer surface of mandible.

Figure 14-13 Posterior view of mandible.

Figure 14-14 Posterolateral view of medial surface of mandible.

Figure 14-15 View of mandible from below.

Figure 14-16 Frontal view of mandible.

Immediately posterior to the symphysis and immediately above the mental protuberance is a shallow depression called the incisive fossa. The fossa is immediately below the alveolar border of the central and lateral incisors and anterior to the canines. The alveolar portion of the mandible overlying the root of the canine is prominent and is called the canine eminence of the mandible. However, this eminence does not extend down very far toward the lower border of the mandible before it is lost in the prominence of the mental protuberance and the lower border of the mandible.

The external surface of the mandible from a lateral viewpoint presents a number of important areas for examination.

The oblique ridge (oblique line, radiographically) extends obliquely across the external surface of the mandible from the mental tubercle to the anterior border of the ramus, with which it is continuous. It lies below the mental foramen. It is usually not prominent except in the molar area (see Figure 14-12).

This ridge thins out as it progresses upward and becomes the anterior border of the ramus and ends at the tip of the coronoid process. The coronoid process is one of two processes making up the superior border of the ramus. It is a pointed, flattened, smooth projection and is roughened toward the tip to give attachment for a part of the temporal muscle.

The condyle, or condyloid process, on the posterior border of the ramus is variable in form. It is divided into a superior or articular portion and an inferior portion, or neck. Although the articular portion, the condyle, appears as a rounded knob when the mandible is viewed from a lateral aspect, from a posterior aspect, the condyle is much wider and oblong in outline (compare Figures 14-12 and 14-13).

The condyle is convex above, fitting into the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone when the mandible is articulated to the skull, and forms, with the interarticular cartilage that lies between the two surfaces and with the tissue attachment, the temporomandibular joint (see Figure 15-2).

The neck of the condyle is a constricted portion immediately below the articular surface. It is flattened in front and presents a concave pit medially, the pterygoid fovea. A smooth, semicircular notch, the mandibular notch, forms the sharp upper border of the ramus between the condyle and coro-noid process (see Figure 14-14).

The distal border of the ramus is smooth and rounded and presents a concave outline from the neck of the condyle to the angle of the jaw, where the posterior border of the ramus and the inferior border of the body of the mandible join. The border of this angle is rough, being the attachment of the masseter muscle (see Figure 15-18) and the stylomandibular ligament (see Figure 15-7).

An important landmark on the lateral aspect of the mandible is the mental foramen. It should be noted that this opening of the anterior end of the mandibular canal is directed upward, backward, and laterally. The foramen is usually located midway between the superior and inferior border of the body of the mandible when the teeth are in position, and most often, it is below the second premolar tooth, a little below the apex of the root. The position of this foramen is not constant, and it may be between the first premolar and the second premolar tooth. After the teeth are lost and resorption of alveolar bone has taken place, the mental foramen may appear near the crest of the alveolar border. In childhood, before the first permanent molar has come into position, this foramen is usually immediately below the first primary molar and nearer the lower border.

It is interesting to note that when the mandible is observed from a point directly opposite the first molar, most of the distal half of the third molar is hidden by the anterior border of the ramus. When the mandible is viewed from in front, directly opposite the median line, the second and third molars are located 5 to 7 mm lingually to the anterior border of the ramus (compare Figures 14-12 and 14-16).