Francis Xavier, the first great missionary of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), was born in Navarre, Spain, on April 7, 1506, and died on the island of Sancian, off the Chinese mainland, on December 3, 1552.

Xavier left his native Spain in 1525 to take up studies at the University of Paris. It was here that he met Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556) and other founding members of the future Society of Jesus. Xavier was at first resistant to Loyola’s attempts to bring about a spiritual conversion in his life. By 1533, however, the two men had developed a close friendship and they were among the group of seven students who, on August 15, 1534, assembled at a chapel in Montmartre and took private vows of poverty and chastity.

After finishing their studies in Paris, the friends aimed to travel to Jerusalem to help in the work of converting the infidels. If this proved impossible (as it did), they pledged to visit Rome and allow the pope to use them in whatever way he thought ”most useful to the glory of God and the good of souls.” Official papal recognition of the new Society of Jesus arrived in September 1540 with the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae.

At this stage, there was little, if any, talk of some of the activities (combating the burgeoning Protestant Reformation; setting up educational establishments) that would come to characterize the Society’s history. However, it was not long before another familiar sphere of Jesuit endeavor began to open up. Over the next four centuries, Jesuit missionaries would travel extensively across Asia, Africa, and the Americas: in the vanguard of such efforts was Francis Xavier, who, in response to a request from the Portuguese king, departed for India on April 7, 1541.

Xavier would spend the next decade evangelizing across southern and eastern Asia. He spent several months in Goa, on the western coast of India, ministering to the sick in the city’s hospitals and striving to win converts among the city’s children. In October 1542 he traveled south to Cape Comorin, where, armed with prayers translated into Tamil, he worked among the local pearl-fishing community. A trip to Malacca (1545) and the Spice Islands (1546-1547) followed, after which Xavier turned his attentions to the two greatest evangelical prizes Asia had too offer: Japan and China.

Xavier arrived at Kagoshima, Japan, on August 15, 1549. He was immediately impressed by what he perceived as the enormous Japanese potential to understand and embrace the Christian gospel. ”We shall never find among heathens another race equal to the Japanese,” he wrote, ”they are people of excellent minds—good in general and not malicious.” Drawing broad, usually reductive, conclusions about the relative worth of various Asian populations would be a hallmark of Christian evangelism throughout the early modern era. Although Xavier met with some resistance from local Buddhist leaders, his two and a half years in cities such as Hirado, Kyoto, and Yamaguchi proved worthwhile. By the time of his departure in 1551 he had won over several thousand converts.

Xavier was back in Goa by January 1552. He set sail for China in May but was destined never to enter the empire’s territories. He was taken ill on Sancian Island in late November and died on the morning of December 3, within sight of the Chinese mainland.

Saint Francis Xavier. Canonized in 1622, Xavier’s memory would inspire missionary priests from Ethiopia to New France to Arizona.

Throughout Xavier’s Asian career the links between evangelism and the colonial enterprise were plain to see. Xavier was a papal legate, but he was also under commission from the Portuguese king, arriving in Goa on board the Santiago in the company of Governor Martim Afonso de Sousa (ca. 1500-1564). There were clear advantages to be wrung from the association with empire. The awe and fear that the European colonists inspired could always be exploited, and satisfaction could be derived from the compulsive European habit of destroying the idols and temples of indigenous faiths. Perhaps most significantly, it could be made abundantly clear to local leaders that allowing missionaries to work in their territories (perhaps even converting to Christianity themselves) might bring military, political, and economic advantages.

That said, Xavier was more than capable of criticizing what he perceived as the lax morality of European settlers. Also, while he shared the prejudices and assumptions of his contemporaries, he did make efforts to genuinely understand the cultures in which he found himself. This, along with a willingness to adapt evangelical strategies according to local circumstances, would emerge as a defining characteristic of Jesuit missionary activity across the globe. Such an ethos certainly carried serious risks.

The accommodationist approach of Jesuit missionaries such as Xavier, Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) in China, and Roberto de Nobili (1577-1656) in India drew enormous criticism from commentators who feared that too much adaptation of the gospel message would result in syncretic, impure versions of the Christian faith. Nor was the work of reacting to local circumstances ever straightforward. In Japan, Xavier had turned to words in the local vernacular to translate concepts such as god, soul, and sacrament. It turned out that he had been badly advised, and the meanings carried by the chosen Japanese words were very different from what Xavier had intended. He was forced to employ Japanese “versions” of Latin words—Deusu, anima, eucaristia—which, to a Japanese audience, were essentially devoid of any inherent meaning.

Perhaps Xavier’s greatest significance lay in his role as an icon and model of all subsequent Jesuit missionary activity. Canonized in 1622, his memory would inspire priests from Ethiopia to New France to Arizona. Relics of the saint would be a much sought-after spiritual commodity during the seventeenth century. The lower part of his right arm would be shipped off to Rome, the remainder would be divided in three and shared between the Jesuit communities in Macao, Cochin, and Malacca. By the eighteenth century, “Xavier-Water,” in which medals or relics of the saint had been immersed, had become a popular central-European cure for fevers and bad eyesight. Even today, his body, housed in the Church of the Bom Jesus in Goa, remains a cherished sight of pilgrimage and adoration.

Xavier’s Arm. Xavier died en route to China in 1552, and relics of the saint became sought-after spiritual commodities during the seventeenth century. The lower part of his right arm was sent to Rome, where it remains in a reliquary in the Church of Gesu.

ZONGLI YAMEN (TSUNGLI YAMEN)

The Zongli Yamen (Office of General Management) was established by the Qing state to deal with the foreign presence in China. Although the Qing state preferred the traditional tribute system that had long regulated China’s relations with foreign countries, China’s weakness in the face of Western military might, combined with the demands of the Western powers for diplomatic relations on an equal basis, made it impossible for China to maintain its traditional model of foreign relations with its assumption of Chinese supremacy and Western barbarity. A new institution was called for to formally manage relations with the Western countries.

In 1861 the conservative Qing court reluctantly agreed to the creation of the Zongli Yamen, which it emphasized was to be a temporary measure to manage relations with the Western countries until they could be removed from China. The Qing court refused to grant the Zongli Yamen complete institutional autonomy, making it instead accountable to the Grand Council and appointing five high-ranking officials to serve as a powerful advisory board. Among the five, the most important was Prince Gong (1833-1898), the uncle of the Tongzhi emperor.

Under the leadership of the reform-minded Prince Gong (Kung) and his capable right-hand man, Wenxiang (1818-1876), the Zongli Yamen played a vital role in the Tongzhi Restoration, the chief aim of which was to strengthen China’s hand in the game against Western imperialism. To this end, in 1862 the Zongli Yamen authorized American missionary W. A. P. Martin’s translation of Henry Wheaton’s Elements of International Law, published in 1836. Widely accepted in diplomatic circles in the West, Wheaton’s work was required reading for those in the foreign service; ignorance of its contents placed Chinese ambassadors at a serious disadvantage.

Besides publishing a translation of Wheaton’s text, the Zongli Yamen also launched a movement to create foreign language schools. Beginning with the opening of a small school in Beijing in 1862, the Zongli Yamen in short order set up similar language institutes in Shanghai, Canton (Guangzhou), and Fuzhou. Despite staunch opposition from the conservative members of the Qing court, Prince Gong and Wenxiang converted the Beijing school to a college; expanded the curriculum beyond foreign languages to include subjects in math, the sciences, and law; and invited foreign teachers to lead instruction. By sponsoring translations of Western texts and financing language schools, the Zongli Yamen sought to provide Chinese diplomats with the training and knowledge they needed to deal with the West.

Less successful was the Zongli Yamen’s project to build a navy. In 1862 the Zongli Yamen purchased from Britain a fleet of ships. Problems arose when the fleet arrived a year later, and Captain Sherard Osborn (18221875) of the Royal Navy, having been promised in writing full command of the fleet, refused to hand over control to his Chinese counterpart. Seeing no other alternative, the Zongli Yamen abandoned its plans for a modern navy. Overall, however, the greater cooperation between China and the West in the late 1860s attests to the relative success of the Zongli Yamen in negotiating relations with the West until its replacement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as mandated by the Boxer Protocol of 1901.

ZULU WARS, AFRICA

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 was fought between Britain and the Zulu nation in South Africa. The war remains one of the most dramatic in both British and southern African history during the colonial period. It marked the end of the independence of the Zulu nation and the entrenchment of British colonialism in South Africa.

The Zulu kingdom emerged early in the nineteenth century along the eastern seaboard of southern Africa under its legendary ruler Shaka Zulu (1787-1828). The background to the war must be located in contestations over land between the Zulu, the Boers, and the British. British adventurers were attracted to Zululand in search of trade and by the 1840s the British colony of Natal had sprung up on the southern borders of Zululand. The expansion of the Boer into the southern African interior from 1835, the attempt by the Zulu to defend their own independence, and the aggressive policy of the British to control South Africa by imposing their authority over the Boer and the Zulu led to a chain of events that resulted in the war of 1879, in which the British suffered humiliating defeat before they eventually subdued the Zulu.

The prelude to the war was the dispute that emerged between the Zulu king, Cetshwayo (ca. 1836-1884), and his brother Umtonga. In 1861 Umtonga fled to the Utrecht district. Cetshwayo offered the Boer farmers a strip of land along the border if they would surrender his brother. But he later rescinded his endorsement of the deal after his brother fled to Natal. The contestation over this ceded land and the boundary issue that developed attracted the British into what could be regarded as a local dispute. Indeed, by the 1870s the British began to adopt a policy that would bring the various British colonies, Boer republics, and independent African groups under common British control. The British high commissioner in South Africa, Sir Henry Bartle Frere (18151884), believed that an independent and self-reliant Zulu kingdom was a threat to this policy. Frere was convinced that economic development and peace in South Africa could only be achieved by curtailing the power of Cetshwayo and the Zulu nation.

To achieve this goal, the British pursued a policy of unwarranted aggression. In 1878, Cetshwayo was presented with an ultimatum as part of the British plan to bring about the confederation of states in South Africa, including Zululand. One of the demands made of Cetshwayo was that he disband his armies within one month and accept a British resident commissioner as co-ruler. This ultimatum was rejected. On January 20, 1879, British troops under the command of Lt. Gen. Lord Chelmsford (1827-1905) invaded Zululand in a three-pronged attack. The initial outcome was a humiliating defeat of British forces by the Zulu army at Isandlwana Mountain. Over 1,300 British troops and their African allies were killed. In the aftermath of one of the worst disasters of the colonial era, the Zulu reserves mounted a raid on the British border post at Rorke’s Drift, but the Zulu were driven off after ten hours of ferocious fighting. The British collapse at Isandlwana left the flanking columns at Nyezane River and Hlobane Mountain vulnerable. But the success at Isandlwana exhausted the Zulu army and Cetshwayo was unable to mount a counteroffensive into Natal. The British rushed reinforcements to South Africa from various parts of the British Empire.

The war entered a new phase in March when Lord Chelmsford assembled a column to march to the relief of the other embattled commands. On April 2, Lord Chelmsford broke through the Zulu cordon around Eshowe at kwaGingindlovu, and relieved Pearson’s column. The defeat of the Zulu king’s forces in two battles demoralized the Zulu. British troops continued to advance toward the Zulu capital, Ulundi, which they reached at the end of June. Chelmsford defeated the Zulu army in the last great battle of the war on July 4, 1879. The Zulu capital of Ulundi was burned and Cetshwayo became a fugitive. But it took several weeks for the British to suppress lingering resistance outside the capital. Cetshwayo was captured on August 28, and exiled to Cape Town. The end of the war had many implications for the Zulu and for the British. The British divided the Zulu kingdom among pro-British chiefs—a deliberately divisive move that resulted in a decade of destructive civil war among various Zulu chiefdoms.

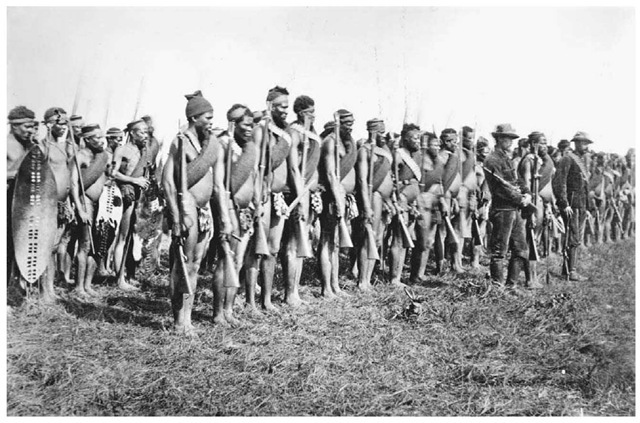

African Warriors in Natal, January 1, 1879. A contingent of African soldiers fighting for the British stand in formation behind British officers in the colony of Natal during the 1879 Zulu War.