Sierra Leone is a strip of mountainous peninsula on the Atlantic coast of West Africa, 67 square kilometers (26 square miles) long and 31 square kilometers (12 square miles) wide, bounded by the Republics of Guinea and Liberia. The first European contact with Sierra Leonean coastline occurred in 1460 when Prince Henry the Navigator’s sea captains voyaged beyond Cape Verde Islands in the quest for a sea route to the spice trade in the Far East. Christianizing the heathens camouflaged a crusading spirit and economic and political motives. Between 1418 and 1460 when the prince died, they had discovered Madeira, Canary Island, Cape Bojador, Cape Blanco, River Senegal, Cape Verde, and Sierra Leone.

In the seventeenth century, the Portuguese established about ten settlements, the major ones being Beziguiche (near the mouth of the Senegal River), Rio Fresco, Portudal, Joala, Cacheo, and Mitombo (in Sierra Leone). These depots sustained the shoe-string commercial empire from Iberia to Java and Sumatra. Portuguese power declined under the attack from other Europeans who took over the settlements, but various river tributaries and swaths of coastline contiguous to Sherbro, Turtle, and Banana Islands remained in the hands of mulatto offspring of Portuguese sailors and other adventurers, some of whom became “African” chiefs. These later contested the missionary work and colonization of Sierra Leone.

British settlement occurred in the bid to abolish slavery and slave trade by attacking the source of supply. The motives in the abolition campaigns by different groups changed over time. For instance, Lord Mansfield’s legal declaration, in the case of the slave John Somerset in 1772, did not fully abolish slavery but catalyzed liberal opinions and philanthropists who promoted the abolitionist cause.

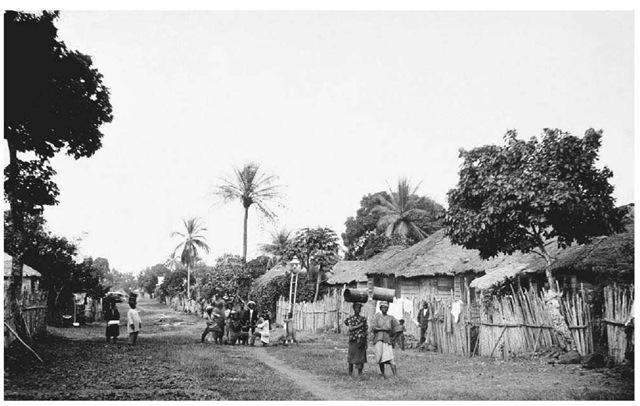

Freetown, Sierra Leone. A neighborhood in the port city of Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, photographed between 1900 and 1933.

The Committee for the Black Poor’s report that the numbers of slaves overburdened its capacity compelled the government’s attention. Initially, Anglicans were prominent because the members of St. John’s Church, Clapham, first concerned with the aftereffects of industrial revolution on the nation, came upon the inhuman slave trade. Other religious supporters, such as the Quakers, joined the affray. Some African ex-slaves, such as the Ghanaian Cugoano and the Nigerian Olaudah Equiano, published their experiences, urged military intervention in the coasts, and pointed to the economic inefficiency of the immoral trade that could be replaced with legitimate trade.

COLONIZING SIERRA LEONE

While sugar planters in the colonies were adamant, it was clear that their profit margin was in decline. Dubbed the Clapham Sect, the evangelicals advocated in Parliament, and organized the establishment of a colony in Sierra Leone as a means of countering the slave trade with a black community that engaged in honest labor and industry. A number of the leaders included Henry Smeatham, the amateur botanist and brain behind the project, the indefatigable Granville Sharp, who finally organized it, William Wilberforce, the parliamentarian advocate, Henry Thornton, the banker who took over the consolidation of the Sierra Leone Company, and later Fowell Buxton, whose book, African Slave Trade and Its Remedy (1841) would summarize the basic contentions: deploy treaties with local chiefs to establish legitimate trade, use trading companies to govern, and spread Christianity to civilize and create an enabling environment.

The Sierra Leone experiment took three phases: On May 10, 1787, Captain T. Boulden Thompson arrived in Granville Town, situated in the ”Province of Freedom” (as the settlement was called), with a few hundred black men and white women. By March the following year, one-third died because of harsh weather and infertile soil that had an underlying gravel stone. In 1791, as the Committee of the Privy Council heard the appeal against the slave trade, the Sierra Leone Company was incorporated, and Granville Town, a small community with only seventeen houses, relocated near Fourah Bay. Disaster struck when a local chief, Jimmy, sacked the town.

To salvage the colony, the British Buxton’s book linked the experiment with the fate of African Americans who were promised freedom and land for fighting for the British during the American Revolution. The British lost but sent them to Canada, West Indies, and Britain. The experience in Nova Scotia was brutally racist, with little access to agricultural land. Thomas Peters, a Nigerian ex-slave, traveled to London to complain. He met Sharp, who enabled twelve hundred African Americans to sail for Freetown in May 1792. They arrived with their ready-made churches and pastors: Baptist, Methodist, Countess Huntingdon’s Connection, and a robust republican ideology to build a black civilization based on religion. Their charismatic spirituality set the tone before the Church Missionary Society (CMS) was formed; their dint of hard work consolidated the colony through attacks by indigenous Temne chiefs at the turn of the 1800s.

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

In September 1800, 550 ex-slaves, the “Maroons,” arrived. These fought their slave owners in Trelawny Town, Jamaica, in 1738-1739 and set up free communities. But in 1795, hostilities broke out again with the slave holding state. Deported to Nova Scotia, they bombarded the government with petitions, memoranda, and sit-down strikes between 1796 and 1800. George Ross, an official of the Sierra Leone Company, was asked to organize their repatriation to Freetown. The Sierra Leone Company ruled the colony for seven years before the British government declared it a British “crown” colony in January 1808. But the French attack in 1894 hastened the conversion to a Protectorate status in 1896.

Before then, major transformations followed the Slave Trade Abolition Act of 1807 that provided for naval blockade against slave traders, and installed a Court of Admiralty that would seize slave ships and resettle the recaptives in Freetown. A process of evangelization intensified when the CMS started work in Sierra Leone with German missionaries in the 1840s. Soon, it became the dominant Christian body, enjoying the government’s patronage while the Catholic and Quaker presence remained weak. The recaptives (67,000 in 1840) soon outnumbered the settlers, became educated, massively Christianized, enterprising, and imbued with the zeal that Africans must evangelize Africa. Representing the first mass movement to Christianity in modern Africa, they carried the gospel and commerce to their former homes along the coast. By the end of the nineteenth century, argued P. E. H. Hair, Sierra Leone “provided most of the African clerks, teachers . . . merchants, and professional men in Western Africa from Senegal to the Congo.” Freetown became the “Athens of West Africa” (Hair 1967, p. 531).