1853-1902

Cecil John Rhodes, a mining entrepreneur, colonial politician, and empire builder, was born in Bishop’s Stortford (Hertfordshire, England) as the fifth son in a family of eleven children headed by Francis William Rhodes, the local vicar, and Louisa Taylor Peacock.

Cecil Rhodes was educated at the local grammar school, supervised by his father. A wished-for higher education in Oxford did not materialize. Instead, Rhodes went to South Africa in 1871 to join his eldest brother Herbert, a cotton planter in the British colony of Natal. On his arrival, Cecil left for the newly discovered diamond fields in Griqualand West. Rhodes set himself up as a cotton planter, but he was unsuccessful and became one of the region’s many diamond prospectors within the year.

The brief Natal experience made Rhodes aware of his latent managerial skills, which he later exploited to the maximum, first as manager of his brother’s diamond claims at Kimberley, and later as a businessman in his own right and as a politician. In the social conundrum of the diamond mines of the early 1870s, Rhodes formed a group of close friends, including John X. Merriman (1841-1926), a member of the Cape Legislative Assembly and future prime minister, and John Blades Currey (1829-1904), secretary of the British administration in Griqualand West. They introduced Rhodes to colonial politics.

By 1873 Rhodes had accumulated enough capital to go to Oxford University. The first phase of his Oxford career was short and incomplete, and it would take until 1881 and several more short periods of study before Rhodes acquired a degree. Although he was admitted at the Inner Temple in London (one of the traditional English ”law schools”) in March 1876, he never seriously pursued a career in the law. Though not much of an academic himself, Rhodes’s relationship with academia extends to the present day with a legacy of scholarships and fellowships, the Rhodes House Library in Oxford, and funds set up to support several South African universities. In 1891 Rhodes received an honorary degree from his alma mater.

In the mid-1870s the diamond industry went through a crisis and rapid change. Adverse weather, the need for complex technologies to work hard rock in deep open pits, and the resulting squabbles between black and white small-claim holders led to unrest and the departure of many diggers from the business. On his return from Oxford, Rhodes positioned himself in the camp of the larger claim-holders and colonial authority. With his partner, Charles Dunnell Rudd (1844-1916), Rhodes strongly advocated rationalization and amalgamation of the mines, not only for the common good of the mining industry, but also with personal motives.

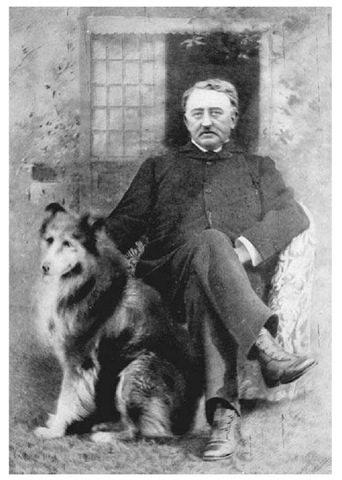

Cecil Rhodes. The nineteenth-century British diamond magnate, colonial politician, and empire builder, photographed with his pet collie.

By the late 1880s, the De Beers Consolidated mining company, grown out of the De Beers mine set up by Rhodes and Rudd, had turned into a worldwide concern with a board in the Cape and in London and a virtual monopoly over diamond production and trade from South Africa. The amalgamation of the mines also meant extensive rationalization of business practices. De Beers introduced new systems of labor control, including the reorganization of black migrant labor into closed compounds, and rigorous and systematic strip searches of workers to prevent theft and smuggling of diamonds.

The enforcement of labor-control measures went hand in hand with British imperial expansion and the annexation of Griqualand West to the Cape Colony. It bought Rhodes a seat in the Cape parliament, and made his labor-control laws and institutions a model for twentieth-century South Africa.

Rhodes’s entry into Cape politics in 1881 was forceful and set the tone for his imperial ambitions and handiwork in later years. He became the spokesman for the mining industry, pushing forward the Diamond Trade Act of 1882 in parliament, with the help of the Cape Argus newspaper, which he had bought for the purpose. Mining interests were soon allied to an expansionist imperial interest when Rhodes successfully argued for the disannexation of Basutoland (now Lesotho) from the Cape Colony and the expansion of British rule toward the north of Griqualand West in order to curb both Afrikaner and Tswana ambitions for control over land and water in the area.

After 1886, when gold was first prospected on the Witwatersrand, the northward expansion of British colonial control increased its pace. Rhodes was interested in gold, but decided to go for the exploration of this mineral north of the Limpopo River in the Ndebele kingdom, thus bypassing the Boer-controlled South African Republic (Transvaal) and at the same time leading the British effort in the scramble for this part of Africa, now contested by Britain, Germany, Portugal, and Belgium.

The formation of the British South Africa Company (BSAC), chartered by the British government in 1889, allowed Rhodes and his partners to exploit and extend administrative control over a vast, if ill-defined, area of southern and central Africa. Within a couple of years, the BSAC not only annexed most of the territory now known as Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia), but the company also incorporated what are now Zambia and Malawi by way of treaties with local leaders. Underlying the BSAC’s actions was a promise to populate the areas brought under its control with settlers, which would allow for an effective British occupation against contending European powers, and introduce the necessary capitalist development to the interior at minimum cost.

In the Cape, Rhodes’s political star was rising. From the mid-1880s, Rhodes supported the policies of the powerful Afrikaner Bond, a political party founded in 1880, with regard to the control of African land ownership, franchise, and labor in the Cape. Through judicious agreements with the Afrikaner Bond and some of the liberal parliamentarians, Rhodes managed to become prime minister of the Cape Colony in 1890. When he lost the support of the liberals in 1893, a general election brought him back stronger and with enhanced support from the Afrikaner Bond.

Rhodes’s second ministry, in which he also acted as minister for Native Affairs, saw the inclusion of all the remaining independent African polities into the Cape Colony. In Britain, his status as a colonial politician was confirmed with his appointment to the Privy Council, the traditional council of advisors to the British Crown, similar to a council of state, in 1895.

The construction of a railway line between the Cape and Transvaal in 1892 was popular with the Bond, but eventually led to a sharp conflict with the South African Republic led by Paul Kruger (1825-1904). In the next four years, the conflict built up and eventually led to a plan to incorporate the South African Republic. Rhodes and others, backed by British businessmen on the Witwatersrand and the British colonial secretary, made use of a trumped-up conflict about disenfranchised British immigrants (Uitlanders) in the South African Republic to stage an armed overthrow.

Leander Starr Jameson (1853-1917), a BSAC agent, invaded the Republic on his own accord, and against Rhodes’s wish to postpone the invasion, in late 1895 with the British South Africa Police Force, only to find that there was no support from inside. The raid forced Rhodes to resign and lost him much of the Afrikaner sympathy he had so carefully built up. It also caused a final rift between Afrikaners and the British, both in the Cape and the Boer republics. The affair also lost Rhodes his position as managing director of the BSAC and threatened the charter of the company. It was only Liberal parliamentarian Joseph Chamberlain’s (18361914) support of Rhodes before a House of Commons inquiry, in exchange for Rhodes’s silence about the former’s complicity, that prevented the revocation of the charter.

In the aftermath of the raid, the Ndebele of Southern Rhodesia rose against the white settlers in their area, and they were soon followed by the Shona people. Rhodes intervened personally and managed to diffuse the uprising by initiating successful secret negotiations with the Ndebele leadership, against the wishes of the white settlers. One result of the uprising was that the British government for the first time intervened directly in BSAC affairs by appointing a resident commissioner to the area. The era of colonialism and settler domination had started.

Despite the political setbacks of the 1890s, Rhodes returned to the political scene of the Cape Colony in the 1898 election, now as leader of the so-called Progressives in the Cape parliament, and against the Afrikaner Bond.

When the latter party won the general election, Rhodes’s role in Cape politics was finally over.

In the last four years of his life, Rhodes stayed in England for a considerable time. He also took time to fight legal battles against accusations made over his role in the Jameson Raid, and against the Polish fortune-seeker Princess Catherine Radziwill (1858-1941), who first tried to attach herself to Rhodes and later—when unsuccessful in her attempts—blackmailed him. Suffering from deteriorating health, Rhodes died at his Cape cottage on March 26, 1902. At his own request, he was buried on the Matopo Plateau in Southern Rhodesia two weeks later.