Pan-Africanism is an internationalist philosophy that is based on the idea that Africans and people of African descent share a common bond. Pan Africanism, therefore seeks the unity and autonomy of African peoples and peoples of African descent; it is also a vision dedicated to fulfilling their right to self-determination. African diasporas—the global dispersion of people of African descent from their original homelands—emerged through slave trading, labor migration, commerce, and war. Imagining home, through a collective identity and cultural identification with Africa, Pan-Africanists mobilize for the continent’s restoration, prosperity, and safety. Pan-Africanism allows African and African Diaspora communities to transcend the status of ethnic minority or oppressed nationality by replacing it with the consciousness of being “a nation within a nation.”

Colonial degradation took many forms in the African world, depending on the varying policies of Britain, Portugal, France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, or the United States. These policies included direct military occupation, economic subordination through labor exploitation and the regulation of trade relations, cultural imperialism, indirect rule using traditional or even manufactured tribal leaders, promises of citizenship for select Africans, and seemingly benevolent development programs.

The attitudes of imperial officials were far from monolithic. Some insisted Africans were racially inferior and needed to be controlled through corporal punishment, including rape and the chopping off of limbs; others saw African peoples as primitive yet noble, even potential equals someday with proper mentoring over time.

An idea of Africa as ”the dark continent” was created over time, by both official intellectual and government institutions and popular culture. Africa came to be seen as suffering from dependency complexes and as unfit for self-government. Importantly, racist viewpoints did not always preclude recognition of African elites, who could function on many levels as modern ”credits to their race” or, alternatively, as keepers of ethnic wisdom and traditions. Close engagement with such elites was inherent to the civilizing mission and a crucial component of “enlightened” imperial government.

The efforts of African peoples to achieve independence and emancipation were distinguished by collecti-vist economic planning, defense against discrimination and brutality, a people-to-people foreign policy across national borders, community control of education, and a rethinking of religious and ethnic practices. Uncritical attitudes toward the nation-state often thwarted the full democratic potential of anticolonial movements.

The Pan-African movement has contributed significantly to the development of African nationalism, antic-olonial revolt, and the postcolonial governmental strategies of African nation-states. The major torch-bearers of the modern Pan-African movement were the African American W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey, a native of Jamaica. Strong foundational pillars include George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, C. L. R. James, and Walter Rodney.

W. E. B. DU BOIS

As a scholar and advocate, W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) endeavored to make Africa central to world civilization. Among the foremost historians, sociologists, literary figures, and politicians of his generation, he foreshadowed in his many publications the future significance of Africa in an era distinguished by unapologetic subordination of the continent. Believing that the enslavement and colonization of African peoples was not only an indignity, but a burden to Western civilization, Du Bois understood what few ministers of foreign affairs, travelers, and journalists of the early twentieth century could: the necessity of involving peoples of African descent in politics and government.

Du Bois, with the Trinidadian attorney Henry Sylvester Williams, organized the first Pan-African Conference of 1900 in London. Subsequently, he chaired four Pan-African Congresses in 1919, 1921, 1923, and 1927, which gathered in London, Paris, Brussels, Lisbon, and New York City (one congress having sessions in two cities). Du Bois played a leading role in shaping protest against colonial land theft and global racial discrimination; he drafted letters to European and American rulers, calling on them to fight racism and promote self-government in their colonies, and to demand political rights for blacks in the United States. Arguing that land and mineral wealth in African colonies must be reserved for Africans, whose poor labor conditions must be ameliorated by law, Du Bois argued that Africans had the right to participate in government, to the extent their development permitted. Basing his claims on the human rights standards of both the United States and Soviet Union, Du Bois confidently predicted—though without ever quite overcoming the elitist perspective embodied in his notion of a Talented Tenth—that Africa would be governed by Africans in due time.

MARCUS GARVEY

Whereas W. E. B. Du Bois focused on the production of professional scholarly literature and petitioning racist and imperial regimes, Marcus Garvey (1887-1940) took up the task of building a Pan-African movement of everyday people and propagated for the first time a global vision of black autonomy. Through mass-oriented journalism, uplift programs promoting health, alternative education, entrepreneurship, and the trappings of military regalia, Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) invented notions of provisional government for African peoples. Garvey’s doctrine created an image of the continent as a homeland for disenfranchised African Diaspora communities, restoring pride in an African past and confidence in a vibrant destiny, and inspiring art, music, and literary representations.

At its height, from 1917 to 1934, UNIA functioned in the United States, the Caribbean, and Latin America, and had an inspirational influence on the anticolonial struggle in Africa. Garvey’s ideas found a mixed reception in Africa. The Harry Thuku revolt in Kenya has been partially attributed to Garvey’s inspiration. In contrast, Kobina Sekyi of Ghana resented the notion that Garvey was Africa’s provisional president. Garvey also saw some of his notions of Africa challenged. He became a critic of Liberia’s ruling elite, and his “Back to Africa” scheme was partially undermined by growing awareness of African slavery and feudal class relations.

Garvey, an autodidact, was at times unpolished, romantic, or bombastic in his intellectual claims. His claims about the various African personalities and civilizations he wished to defend were not always factually accurate. Nonetheless, without a professional or scholarly pedigree, and possessing limited resources, Garvey inspired political ambitions and a desire for independence in multitudes of ordinary people of African descent.

GEORGE PADMORE

George Padmore (1903-1959), a native of Trinidad, produced books, journalism, and strategic guides— backed between 1928 and 1935 by the authority of Moscow and the Communist International—that helped create a global network of black workers and fomented labor strikes and anticolonial revolts. Early in his career, Padmore was hostile to both Garvey and Du Bois, for what he saw as their insufficient resistance to the empire of capital; later, out of necessity, he modified his stance toward their legacies, while continuing to defend his own uncompromising positions.

During World War II, the Soviet Union subverted socialist ideals by, among other means, forging an alliance with Britain, France, and the United States against Italy, Germany, and Japan. When the Soviets ended their policy of promoting national liberation struggles in the African and Caribbean colonies, Padmore was asked to encourage friendship with ”the democratic imperialists.” He refused this absurdity. Surfacing in London, he formed the International African Service Bureau with C. L. R. James; he defended Ethiopia from Italian invasion, and continued advocating the destruction of all colonial regimes worldwide.

Working with future African independence leaders— Sierra Leone’s Isaac Wallace-Johnson, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah—Padmore maintained and extended his vast network. These efforts culminated in the Fifth Pan-African Congress of 1945, held in Manchester, England. A watershed event, this assembly gathered for the first time vast numbers of African activists, many of whom were trade unionists or students. This time few proposed merely lobbying colonial authorities. Rather, a commitment was made to mass politics and armed struggle, if necessary, as the means to establish self-government on the African continent. Padmore ended his career as Nkrumah’s advisor on African affairs upon Ghana’s independence in 1957.

KWAME NKRUMAH

Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972) was one of the two greatest Pan-African statesmen, along with Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere. As with Nyerere, Nkrumah’s vision of federation and cooperation for the liberation of the entire African continent transcends the mixed legacy of his domestic governance.

Nkrumah employed ”positive action”—strikes and other forms of nonviolent civil disobedience—as a means to overthrow British colonialism. He confronted tribal and customary authorities in Ghana and initiated modern development projects. Promoting the idea of the African personality and seeking to incorporate and unify Islamic, Christian, and African theologies and ethnic traditions, Nkrumah made Ghana a center for African American expatriates. Nkrumah linked Ghana with Sekou Toure’s Guinea and Modibo Keita’s Mali in a three-nation federation. He also sponsored the All African Peoples Conference of 1958, which was attended by various luminaries of the national liberation struggle, such as Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, Kenya’s Tom Mboya, and Algeria’s Frantz Fanon. At the conference, anticolonial trade union movements were organized, and further federations of nation-states were conceived.

The idea of Pan Africanism took a new turn with the formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963. The OAU was founded to promote unity and cooperation among all African states and to bring an end to colonialism in all parts of the continent. Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia, brokered an uneasy compromise between Nkrumah’s call for the total unification of Africa and the desire for autonomous nation-states. A collective commitment was made to liberate southern Africa from colonialism in the future. Yet colonial nation-state boundaries were to be respected in the post-colonial era, thus creating a country club of ruling elites whose governments rarely interfered in each other’s affairs on behalf of ordinary people waging democratic struggles. The fall of Nkrumah’s regime in 1966 came through military coup and imperial intervention. His rule was increasingly an undemocratic populist dictatorship, even as he began to articulate the neocolonial dilemma—the continuing dependency of seemingly sovereign African nation-states. Nkrumah lived out his last years in exile in Sekou Toure’s Guinea.

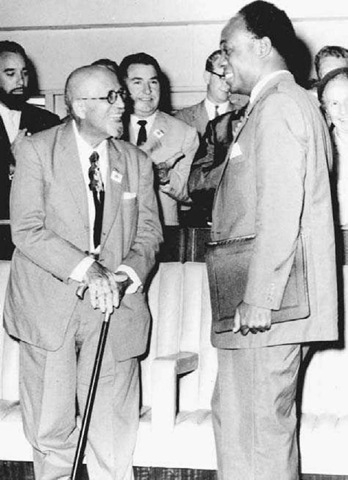

Kwame Nkrumah and W. E. B. Du Bois, Ghana, 1962. Kwame Nkrumah (second from right), president of Ghana, converses with the American scholar and exponent of Pan-Africanism W. E. B. Du Bois shortly before the opening of the World Peace Conference in Accra, Ghana, on June 21, 1962.

JULIUS NYERERE

The Tanzanian leader Julius Nyerere (1909-1972) developed his Pan-African perspective slowly, but grew into a remarkable politician. After foiling several early coup attempts, and operating under the shadow of Cold War intrigue, he cautiously united mainland Tanganyika with the Zanzibari islands off the Swahili coast. He attempted but failed at the creation of an East African federation with Kenya and Uganda. Nyerere then developed a vision of self-reliance rooted in the values of the African peasantry. Terming this vision Ujamaa Socialism, he introduced resolutions that aimed at excluding capitalists and major property owners from political power. He spoke and wrote eloquently in Swahili, which he made widespread as a national and Pan-African language. In the same spirit of unity, he sought to reduce ethnic conflict and permitted intellectual autonomy at Dar es Salaam’s university, where professors and students were often critical of him.

Nyerere welcomed a global expatriate African community, continuing the legacy of Nkrumah’s Ghana, and sponsored guerilla forces fighting for the liberation of Mozambique, Angola, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. He stood up to the aggressive impulses of Uganda’s Idi Amin, whose overthrow he later sponsored, following a war between Tanzania and Uganda. Yet, Nyerere too eventually became a populist autocrat of a one-party state. His compulsory state plans for rural development according to the principles of Ujamaa proved to be a failure. Even his internationalism had its limits.

C. L. R. JAMES

When Tanzania sponsored the Sixth Pan-African Congress in 1974, the Call was drafted by former SNCC and Black Panther activists under the guidance of C. L. R. James (1901-1989). A native of Trinidad, James had a long career as a mentor and colleague of postcolonial statesmen that cannot be reconciled easily with his life as an insurgent socialist political philosopher advocating the overthrow of states and ruling elites. Indeed, James’s life and work embodied the contradictions of the Pan-African movement in the postcolonial era.

The 1974 Congress, which was supposed to unify grassroots activists from across the globe under the sponsorship of a progressive state, imploded before it began. Nyerere collaborated with postcolonial Caribbean governments to exclude Caribbean insurgents, such as Maurice Bishop of Grenada’s New Jewel Movement. Furthermore, prior to the Congress, Nyerere had jailed radical democrats in Tanzania, such as A. M. Babu, and in so doing had revealed the limits of the Pan-African vision and the necessity of what has come to be called ”a second liberation of Africa.” In the end, in a decision that perhaps suggests his unique political legacy, James boycotted the Sixth Pan-African Congress, even though he had traveled globally to organize it.

WALTER RODNEY

Walter Rodney (1942-1980), a native of Guyana, perhaps best imagined the Pan-African philosophy and practice necessary for a second liberation. As a scholar and activist, Rodney sought to reconcile the secular modernist tradition of class struggle-based Pan-Africanism with the prophetic cultural, nationalist, and theological visions of ordinary African and Caribbean peoples. He did not work in the service of populist state power, but rather organized everyday people against state power. Rodney’s charismatic teaching inspired great democratic rebellions, against the postcolonial regime in Jamaica in 1968 and during the late 1970s in Guyana, for which he was assassinated. As a professor of history in Julius Nyerere’s Tanzania, he taught, among other lessons, how Europe historically had underdeveloped Africa through its colonial policies. Yet it is Rodney’s famous conference paper at the Sixth Pan-African Congress that most clearly suggests what are perhaps the most instructive perennial questions concerning African struggles for liberation. Rodney stressed—and this brief survey suggests he is correct—that an examination of which classes led the national liberation struggle, focusing especially on conflicting desires at the start of the post-colonial phase, is crucial to evaluating the legacy of Pan-African freedom struggles.

PAN-AFRICANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The new millennium witnessed the OAU’s transformation into the African Common Market, devoted to seeking the continental integration of financial markets and the facilitation of labor exploitation, with the blessings of American empire. Globally, progressives can only lament that the United States does not offer enough financial aid to Africans nor sufficiently forgive their governments’ debts—in short, many defenders of the continent believe the imperialists are not involved in Africa enough! The contemporary moment is for many a time in which African peoples’ struggle to delink from empire amounts to a dream, and subordinate African nation-states and ruling classes have given up even the pretext of such a possibility. A rethinking of the Pan-African community-organizing tradition may hold out some hope of finding new pathways and refashioning ideas about the future of self-government.