The Monroe Doctrine was enunciated by President James Monroe (1758-1831) in an annual message to the U.S. Congress in 1823. The main concern of Monroe and his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), was the future of Hispanic America. Hispanic America had struggled for independence from Spain, and new republics sprang up from Mexico to Chile, influenced in part by the examples of French and U.S. republicanism. The United States welcomed the emergence of the new republics in most respects; but the absolute monarchies in Europe, notably Russia and the briefly resurgent monarchical regime in France, looked askance at the creation of the new states and sought to isolate them diplomatically.

While the United States began the process of recognizing the Spanish American republics in 1822, France in 1823 urged Spain to reimpose the power of the House of Bourbon in Spanish America. A program of reconquest backed by the Holy Alliance (Russia, Prussia, and Austria) and endorsed by the Vatican was a matter of deep anxiety in Spanish America, the United States, and Britain, which was aiming to establish strong commercial ties with the fledgling republics. Indeed, the British foreign secretary, George Canning (1770-1827), even proposed that Britain and the United States should together warn Spain and France against intervention. Adams, meanwhile, had a secondary anxiety: the drive of Russia to extend its influence along the Pacific coast of North America from Alaska to California, then still part of Mexico.

The Monroe Doctrine amounted to a statement that the United States would treat any attempt to extend European influence in the ”New World” as a threat to its security. This was, in effect, an assertion that the Western Hemisphere was closed to European colonization, whether by powers like Russia with new expansionist aspirations or by old colonial powers like Spain, which aimed to recuperate colonies lost in the wars of independence. The immediate impact of the Monroe Doctrine was limited, both because the powers of mainland Europe were too preoccupied with events closer to home to put up a united front in the Americas, and because Spain was too debilitated by the effects of warfare at home and in the former colonial empire to launch a project of reconquest.

Enjoying some support from the British, the most formidable naval power of the century, the Monroe Doctrine remained in place. It was insufficient, however, to prevent brief interventions in the 1860s by Spain in Santo Domingo and France in Mexico. There were two reasons for this: the weakness of the U.S. Navy, which was smaller than the Chilean navy; and deep divisions in the United States, which culminated in the American Civil War (1861-1865). Only after the consolidation of the frontier in the West and the assertion of the United States as a major naval power in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans could the Monroe Doctrine be applied without British support.

The final defeat of Spain in the Caribbean and the Pacific during the War of 1898 meant that the United States could now assert an ascendancy in northern Latin America and the Caribbean and consolidate U.S. influence in southern South America. Complemented by the Roosevelt Corollary, enunciated by President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) in 1904, the Monroe Doctrine was used by successive U.S. administrations to justify interventions ostensibly designed to preempt European, especially German, invasions of small nations, usually to collect outstanding debts. Thus the Monroe Doctrine provided the main rationale for a sequence of interventions in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nicaragua, and the port of Veracruz (Mexico) during the next three decades. These interventions achieved the goal of forestalling European involvement at the expense of awakening widespread and, in some countries, sustained nationalist movements.

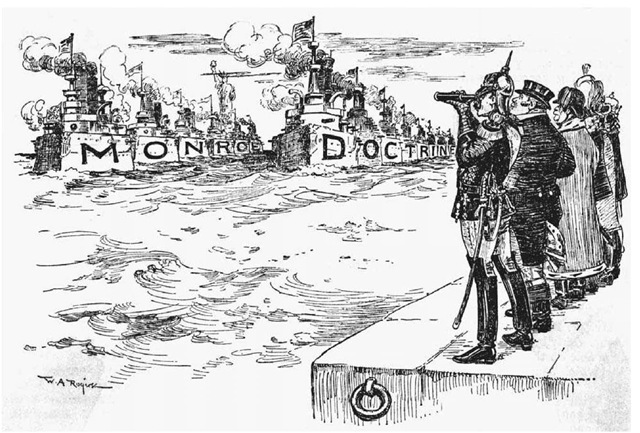

European Potentates Observe Naval Might. This cartoon, in which figures representing the countries of Europe observe the naval power of the United States, appeared in the New York Herald.