When young radicals overthrew the Tokugawa shogun in 1868, their overriding goal was to create a strong, sovereign Japan that could overcome the unequal treaties imposed by the Western powers. Over the next seventy-seven years, until defeat in World War II (1939-1945), Japan would assemble a vast empire in east Asia and the western Pacific. Yet the course of acquiring this empire was not predetermined but buffeted with disagreement and circumstance. Indeed the new leadership split over a plan to invade Korea in 1871. That action was blocked, but in 1875 Tokyo sent a fleet to the isolated nation, forcing Korea to open up to Japanese trade and contact.

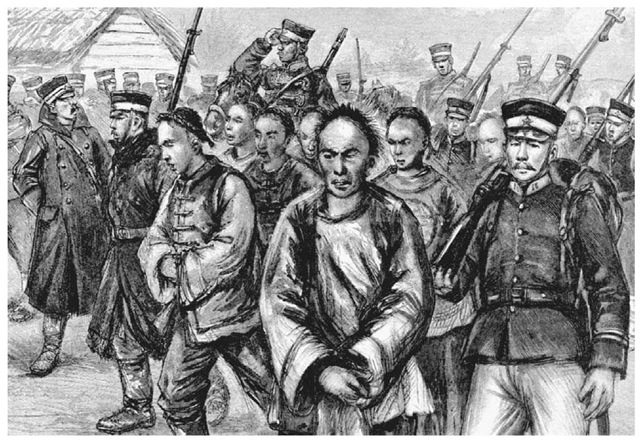

Chinese Prisoners During Sino-Japanese War. Japanese soldiers march Chinese prisoners during the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). The war marked the beginning of Japan’s policy of imperial expansion.

BUILDING AN EMPIRE

For the next two decades Tokyo vied with China for influence in Korea, finally clashing in the short Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. Japan’s startling victory in this conflict yielded its first major colony, the island of Taiwan (or Formosa). The Sino-Japanese War also made Japan one of the powers in China, with treaty port rights and extraterritoriality. Armed with this new status Japan participated in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. Its forces marched into Beijing with the Westerners, and Tokyo signed the Boxer Protocol, which granted it the right to station troops at various locations around northern China. Yet Japan was profoundly unhappy with moves by the Russian Empire to control both northeast China (Manchuria) and Korea, and joined with Britain in an alliance to force Russia to retreat. The two nations clashed in the Russo-Japanese War of 190405, and Japan’s victory in this conflict left it in a much stronger position on the Asian mainland. Japan soon gained complete control over Korea, made a formal part of the empire in 1910, as well as railway concessions and ports in southern Manchuria. Japan also gained the southern half of the Sakhalin Island off the coast of Siberia.

Tokyo never completely fixed upon a colonial policy but increasingly moved toward “assimilation” for Koreans and Chinese in Taiwan. The colonized were compelled to use Japanese surnames, to be schooled and educated in Japanese language, and to revere the Japanese emperor. When Koreans traveled to Japan, however, they discovered that few Japanese accepted them as equals; discrimination against Koreans was blatant and often deadly. World War I (1914-1918) brought Japan new opportunities; in 1915 it presented a weakened China with 21 Demands, designed to increase its power on the mainland. Japan also grabbed German territories in the area, notably the German-held islands in the southwest Pacific that Japan held until captured by the Allies in World War II. Unlike the Koreans and Chinese who could plausibly be “Japanized” few felt that the Pacific Islanders could be assimilated. Islands such as Saipan were transformed mostly by Japanese immigration.

JAPANESE EMPIRE, KEY DATES

1868: Tokugawa shogunate overthrown by radicals; Meiji period begins

1875: Japan invades Korea and establishes trade supremacy

1879: Japan annexes Ryukyu Islands

1895: Control of Formosa (Taiwan) following victory in Sino-Japanese War

1900: Japan aids China in ending Boxer Rebellion; establishes military outposts in China

1905: Japan wins Russo-Japanese War and gains more control of Asian mainland

1910: Japan annexes Korea and begins Japanese enculturation

1912: Yoshihiro succeeds to throne, Taisho period begins

1914: Japan declares war on Germany and enters World War I

1915: Japan presents China with 21 Demands

1917: Lansing-Ishi Agreement reinforces Japanese interests in China

1918: Japan launches Siberian Expedition to gain foothold in Russia; World War I ends

1919: Korean colony displays nationalism in March 1st Movement; Japan counted among “Big Five” at Treaty of Versailles

1921: Prime Minister Hara Takashi is assassinated; Japan signs disarmament agreements at Washington Conference, relinquishing claims to Chinese territory

1922: Agrees to naval limits in Pacific in Nine-Power Treaty

1923: Kanto earthquake levels Tokyo in September

1925: Japan becomes last Allied nation to withdraw from Russia

1928: Taisho dies and Hirohito becomes emperor

1929: Great Depression affects Japanese economy

1931: Japanese Prime Minister Rikken Minseito is assassinated; Japanese Guandong Army occupies Manchuria, which is renamed Manchukuo

1933: Japan withdraws from League of Nations

1936: Japan signs Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany

1937: Italy joins Japan and Germany to form Axis Powers; Japan begins invasion of China, triggering Second Sino-Japanese War

1941: Japan bombs Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7

1943: Cairo Conference plans return of Manchuria, Taiwan, and Pescadores Islands to China

1944: Japan gains control of Dutch, French, American, and British interests in Asia

1945: U.S. drops atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th; Defeat in World War II leads Hirohito to surrender to Allies on August 14

1946: U.S. General Douglas MacArthur drafts model Japanese constitution

TWENTIETH-CENTURY CHANGES In the 1920s Japan seemed to back away from expansion, becoming more democratic at home and party to naval disarmament agreements signed at Washington in 1921. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929, however, stimulated unrest in Japan and fueled the growth of an ultranationalist movement. The right wing achieved its first big success in September 1931, when Japanese army officers stationed along the railway in northeast China faked a terrorist attack and quickly seized control of northeast China. A vast territory of 30 million people most of whom were Chinese, Manchuria was organized as a puppet state, Manchukuo, by the Japanese Imperial Army, which installed the last Qing monarch as “emperor.”

In July 1937 Japan began an all-out invasion of China. Within six months the Chinese had abandoned most of their coastal cities; within two years much of eastern and central China was under Japanese control, and nearly half of China’s population would live, at least for a time, in occupied areas. It was by far the greatest acquisition of the Japanese Empire to date. Yet China remained an active war theater, and despite puppet governments, Japan could not create a stable political structure. In the north, where the Japanese had long planned expansion and had developed the adjacent territory in Manchukuo, Japan achieved some success in exploiting coal and iron ore. In central and south China Japanese had to rely mostly on confiscation of Chinese enterprises and extraction of agricultural products.

The final saga in Japan’s empire began with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Within six months Japan seized the colonial possessions of the Western powers in southeast Asia, including the oil-rich Dutch East Indies and British Malaya with its tin and rubber. The American Philippines was overrun and much of British Burma. The Japanese occupied French IndoChina, though nominally under Vichy control. Japan called its new empire ”The Greater East-Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

The last gasp of the Japanese Empire was its most impressive yet but Japan failed to take advantage. Allied forces devastated Japanese commercial shipping, precluding the full use of the new colonies. Restive populations who initially welcomed Japanese ”liberation” quickly became disenchanted when their ruler proved even harsher than that of the Western masters. Japan destroyed Western imperialism in southeast Asia, but it created a legacy of anti-Japanese feeling that took decades to erode.

When Emperor Hirohito announced surrender in August 1945, Japan lost all but the home islands. What had been the largest non-Western empire in the modern world was no more. And what legacy did it leave? Perhaps only in Taiwan do individuals acknowledge positive contributions of the experience. In divided Korea, few people see anything but humiliation and suffering in the colonial experience. In China, legacy over Japanese wartime atrocities still clouds relations between the two nations. As for Japan, it has found a new role as an economic giant; using trade rather than conquest to succeed.