Qamate

Supreme god of the Amoxosa Kaffir Negroes, who raise large burial mounds in his honor. These earthworks represent the mountainous island from which their ancestors arrived in Africa after he pushed it to the bottom of the sea. Since only one man and woman survived, Qamate told them to pick up stones and throw them over their shoulders. As they did so, human beings sprang from the ground wherever the stones fell. To commemorate this repopulating of the world after the flood, every passerby deposits a stone on one of the mounds. Resemblance of the Amoxosa version to the Greek deluge account is remarkable, implying a calamitous event both peoples experienced—the destruction of Atlantis.

Q’a'mtalat

The Canadian Kwakiutl Indians’ flood hero, who died in the Great Flood while successfully trying to save his children by removing them to the summit of a high mountain. They became the ancestors of a post-deluge humanity.

Here, as in other traditions among peoples more likely effected by the Lemurian disaster, the story of Q’a'mtalat describes steadily rising waters, not the more geologically violent destruction of Atlantis depicted in East coast myths.

Qoluncotun

Creator deity of the Sinkaietk, or Southern Okanagon Indians, in Washington State. Angered by the ingratitude of their ancestors, he hurled a star at the Earth, which burst into flames. Just before the entire planet was reduced to ashes, Qoluncotun extinguished the conflagration by pushing “a great land” beneath the sea, making it overflow into a world flood. From the few survivors, he refashioned mankind into various tribes.

Q’o'mogwa

“Copper-maker,” leading culture hero of the Kwakiutl, native inhabitants of the Canadian Pacific coast. According to Kearsley, “His exploits are invariably associated with long sea voyages, sometimes to the Land of Ancestors, or the Upper World, beyond the West where the sun sets, or into the middle of the ocean, clearly the Pacific Ocean, where the Copper-maker was also said to exist” (50,51). Q’o'mogwa commanded a magical vessel that took him to all parts of the world, “a self-paddling copper canoe ‘filled with coppers’…probably a sailing craft.”

“Copper-maker” is the self-evident memory of the Lemurian captain of a sailing ship from the mid-Pacific kingdom of Mu, the Kwakiutl “Land of Ancestors,” which dispatched miners to excavate North America’s rich and anciently worked copper deposits. While Michigan’s Upper Peninsula was dominated by Atlantean miners, Lemurian interest in metallurgy was certainly less commercial than spiritual. Adepts of the Pacific Motherland probably used copper primarily for psychic activity, due to its alleged conductivity of various energy forms, a quality still prized in many native cultures throughout the world.

Quaitleloa Festival

The Aztec legend of Tlaloc told how the god of water raised a great mountain out of the primeval sea. His Quaitleloa Festival commemorated the destruction of the world by flood: “Men had been given up to vice, on which account, it (the world) had been destroyed.” Tlaloc’s wife, Chalchihuitlicue, was represented as a torrent carrying away a man, woman and treasure chest, intending to portray Otocoa, “the loss of property.” As though to emphasize the Atlantean identity of Tlaloc, the Quaitleloa Festival took place in the vicinity of Mount Tlalocan, or “Place of Tlaloc,” in nothing less than a ritualized recreation of the final destruction of Atlantis.

Queevet

Worshiped by South America’s Abipon Indians as the white-skinned god of the Pleiades, he long ago destroyed the world with fire and flood. The Abipon regarded Francisco Pizzaro and his fellow Conquistadors as manifestations of Queevet. Their veneration did not, however, prevent the Spanish from exterminating them.

Quetzaicoati

Toltec version of the Feathered Serpent, the white-skinned, light-eyed, blond, bearded man who arrived at Vera Cruz on his “raft of serpents” accompanied by a group of astrologers, scientists and physicians. Quetzalcoatl was the most important Mesoamerican deity, regarded as the founding-father of civilization. The kingdom from which he came across the Atlantic Ocean was called Tollan, the Toltec Atlantis, described as a powerful, island-city of great, red-stone walls, recalling Plato’s portrayal of Atlantean walls constructed of red tufa.

Quetzalcoatl was commonly depicted in sacred art as an Atlas-figure: a bearded man surrounded by symbols of the sea, such as conch shells, and supporting the sky. It is not clear which of the three major migrations from Atlantis with which Quetzalcoatl was associated. In his Maya guise as Kukulcan, he was preceded in Middle America by Itzamna, and must therefore have arrived in either the late third millennium b.c. or after 1200 b.c.

Quihuiti

Literally, “the Fire from Heaven,” third of the global catastrophes depicted in its own square on the Aztec Calendar Stone as a sheet of descending flame. It closed a former “Sun,” or world age, from which a few survivors rebuilt society. The date 4-Quihuitl refers to the penultimate Atlantean cataclysm, in 2193 b.c.

Quikinna’qu

Revered by Native American tribal peoples like the Koryak, Kamchadal, and Chuckchee of coastal British Columbia as “the first man.” He was the only survivor of an island that had been transformed into a whale by the Thunderbird. To escape attack from its talons, the whale dove to the bottom of the sea, drowning everyone on its back except Quikinna’qu, who floated on a log to what is now Vancouver Island. There he married a native girl, whose children became the tribes of the Pacific Northwest.

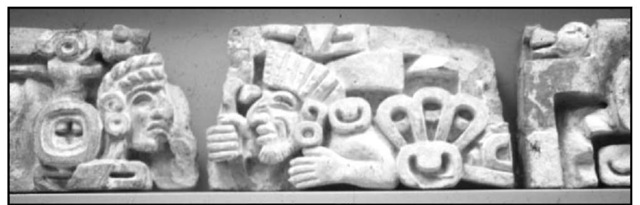

Stone frieze from the ceremonial megalopolis at Teotihuacan, depicting the culture-bearer of Mesoamerican civilization, the Feathered Serpent.