Pleiades

Atlantis means “Daughter of Atlas,” and theAtlantides, or Pleiades, were seven daughters fathered by him. Like the kings listed by Plato, they correspond, through their individual myths, to actual places within the Atlantean sphere of influence, and thereby help to illustrate the story of that vanished empire. The souls of the Pleiades were transformed into the constellation by which they are known because of their great services to mankind in siring the culture-bearers of post-deluge civilizations. They were known around the world for their culture-creating sons by numerous peoples who never knew of each other, but who nevertheless experienced a common impact from Atlantean survivors. Even the remote tribes of Java preserve a tradition that tells how one of the Pleiades mated with a mortal man to sire the human race.

Atlas’ consort was Pleione, from the Greek word, pleio, “to sail,” appropriately enough, because the constellation of the Pleiades is particularly visible from May to November, the sailing season. Pleione means “Sailing Queen”; Pleiades, the “Sailing Ones.” By their very definitions, they exemplify the Atlanteans’ outstanding cultural characteristic; namely, maritime prowess. In fact, the Pleiades appear in Odysseus’ sailing instructions to Phaeacia, Homer’s version of Atlantis (Odyssey, Topic V, 307).

A common theme among the Pleiades was the extraordinary destinies of their offspring, who, like the Atlanteans themselves, were founders of new kingdoms in distant lands. Paralleling Kleito in Plato’s narrative, Alkyone, the leader of the Pleiades, bore royal sons to Poseidon, the sea-god. Her sisters were no less fertile. All their sons or grandsons founded or rebuilt numerous cities and kingdoms. Maia was venerated in Rome until the last days of the Empire as the patroness of civilization itself through her son, Mercury, the god of organized society. The expanse of the Atlantean imperium was encompassed by the Pleiades and their children.

As the Greek scholar Diodorus Siculus wrote in his first-century b.c. Geography: All the rest likewise had sons who were famous in their times, some of which gave beginning to whole nations, others to some particular cities. And therefore not only some of the barbarians, but likewise some among the Greeks refer the origin of many of the ancient heroes to these daughters of Atlas. They lay with the most renowned heroes and gods, and they became the first ancestors of the larger part of humanity” (Blackett, 103). In other words, Western Civilization was born from Atlantis. Diodorus’ characterization of the Pleiades suggests they were not originally mythic figures, but real women, wives of Atlantean culture-bearers, who dwelt in kingdoms which comprised the Empire of Atlantis, and generated the royal lineages of those realms. Long after their deaths, they were regarded as divine, and commemorated as a star cluster.

The Pleiades’ stellar relationship to Atlantis has been cited in Odysseus’ sailing instructions to Phaecia. But their Atlantean significance predated the Odyssey, and spread far beyond Homer’s Greece. The Sumerians associated the constellation of the Pleiades with their version of Atlas, Adad, the volcanic fire-god. The rising of the Pleiades signaled the New Year among the Mayas and Aztecs, as they did for the pre-Inca Chimu and Nazca civilizations of the Andes. Known to the Mayas as Tzab, the Aztecs sighted them along a water channel running parallel to the Sirius-Pleiades Line at Teotihuacan, the imperial capital long since covered by modern Mexico City. When the Seven Sisters ascended the middle of the sky at dawn of the winter solstice, Aztec priests assembled on the summits of the Huizachtleatl Mountains.

The Cheyenne Indians of North America believed that a mother died and took her daughters with her into the night sky to become the Pleiades. Remarkably, this is identical to the Greek version. The Lakota Sioux likewise called them “the Seven Sisters.” No less remarkable was the Incas’ worship of the Pleiades as the Aclla Cuna, “the Chosen Women,” or “the Little Mothers.” These New World interpretations of the Pleiades credibly echo Atlantean contacts with Native Americans in pre-Columbian times. Given their particular identities, the Pleiades correspond individually to the following realms within the Atlantean Empire:

Alkyone: Atlantis itself, through Phaeacia’s Alkyonous.

Claeno: the Azore Islands, through her husband’s reign over the “Blessed Isles.”

Elektra: Troy; her son, Dardanus, was the founder of Troy. Merope: North Africa, the Meropids of Morocco. Maia: Yucatan, the Maia Civilization:

Sterope: Western Italy; her son founded Pisa, the Etruscan Pisae. Taygete: the Canary Islands, from Tegueste, a Guanche province in Tenerife.

Pohaku o Kane

The “Stone of Kane,” an elongated monolith from 1 to 6 feet long, set upright to resemble a column within every Hawaiian household, where it was the center of worship by male family members only. Its location in the hale mua, or men’s eating quarters, reaffirms its ritual association with Mu, the sunken civilization of the Pacific. Kane was a creator-destroyer god responsible for the Great Flood that overwhelmed a former kingdom of immense kahuna, or spiritual power, known variously as Hiva, Haiviki, Kahiki, Pali-uli, etc.

Each Pohaku o Kane was considered a sacred version of an original pillar from that vanished realm, as implied by its waterworn condition. Cunningham observed, “Not just any stone could be used as the Pohaku o Kane. Such a stone was pointed out by Kane during a dream or vision” (84). Like distant Thailand’s La Mu-ang, the Stone of Kane was Hawaii’s simulacrum of a column from some sacred building in lost Mu.

Poseidon

The sea-god in Kritias who, after the creation of the world, was given the island that would later become Atlantis. A native woman he loved provided him with five sets of male twins, progenitors of a royal line. Poseidon honored her hillside home by encircling it with a moat, thereafter creating two more sets of concentric rings of alternating land and water. Atlantologists endeavoring to interpret his myth have been unable to determine if Plato used Poseidon as a symbol for the natural forces which went into the configuration of the island, or as a metaphor signifying the arrival of some outside, unknown, possibly Neolithic or megalithic culture-bearers. Supporting his alien provenance, “Poseidon” is among the few identifiable examples of the long-dead Atlantean language, because the name stands out among his fellow Olympian deities as decidedly non-Indo-European. It derives from a contraction of the un-Greek Posis Das, “Husband of the Earth,” and Enosichthon, or “Earthshaker,” together with the very Greek Hippios, “He of the Horses.” This synthesis implies that Poseidon did indeed come from outside Greece, where he was eventually adopted as one of the supreme divinities. With no linguistic or mythic parallels among eastern cultures, he arrived from the western direction of Atlantis, according to Herodotus: “Alone of all nations, the Libyans have had among them the name Poseidon from the first, and they have ever honored this god.”

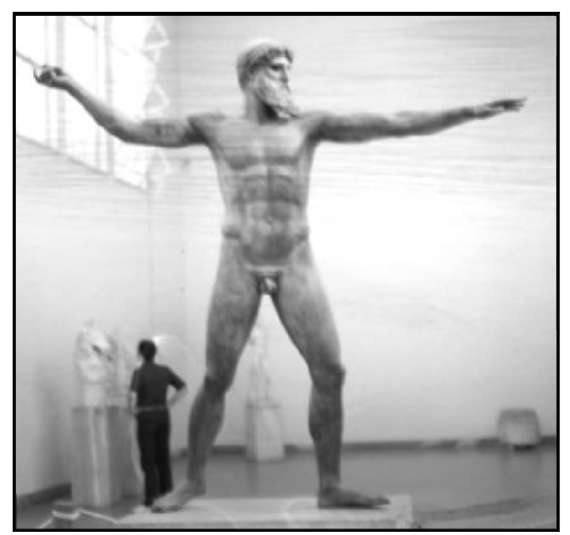

Fifth-century B.C. bronze of Poseidon, the sea-god of Atlantis, National Archaeology Museum, Athens.

In the non-Platonic myth of Poseidon, he loses a contest with Athene for possession of Greece, which may symbolize the Atlanto-Athenian War. Underscoring this interpretation, Poseidon hurls his trident at the Athenian Acropolis, from which a flood gushes forth in a spring.

Poshaiyankaya

Leader of the ancestral Zuni into the American Southwest, following their near annihilation in the Great Flood. Some modern pottery decoration memorializing the ancient catastrophe suggest Lemurian themes, such as the hooked cross and Tree of Life.

Pounamu

The “Green Stone” of New Zealand, mythically associated with the Lemurian Waitahanui. According to New Zealand archaeologist, Barry Brailsford, “It was used as ballast in the oceangoing ships, the double-hulled waka ships. These ships had a very large sail and went to all parts of the world.” He described the Pounamu as “harder than steel,” cut today only by diamond saws. “Black Elk, the great North American Indian chief, came to New Zealand to collect the ancient stones which he said his people once used” (A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Armageddon, 121). The Green Stone’s connection with New Zealand’s Waitahanui and the appearance of “mu” in its name define the Pounamu as a religious relic from Lemurian times. (See Mu, Waitahunui)

Poverty Point

The name of an archaeological find in northeastern Louisiana, the oldest city in North America, dated to circa 1500 b.c. Poverty Point was a concentric arrangement of alternating rings and canals interconnected by causeways radiating outward from a central precinct and fronted by a large earthwork built to resemble a volcano. The site is fundamentally a mirror-image of Plato’s description of Atlantis, an identification reaffirmed by sudden cultural florescence at Poverty Point in 1200 b.c., just when Atlantis was finally destroyed, and some of its survivors sought refuge in what is now America.

Powako

The Delaware Indian flood hero who led their ancestors out of a natural disaster that sank “the first land, beyond the great ocean.” The oldest branch of the Algonquian family, the Leni-Lenapi, displayed white racial characteristics so pronounced that some early settlers considered them members of the fabulous “Lost Tribes” of Israel. The Delaware, in fact, called themselves the Leno-Lenape, or the “Unmixed Men,” as some distinction for their descent from white-skinned flood survivors led by Powako.

Prachetasas

“Sea-kings” whose kingdom plunged to the bottom of the ocean. Hindu myth tells of 10 Prachetasas, the same number of kings, according to Plato, who ruled the Atlantis Empire.

Pramzimas

The Lithuanian Zeus, who, fed up with the iniquities of mankind, dispatched a pair of giants, Wandu (wind) and Wejas (water) to destroy the world. Pramzimas halted the deluge just in time to save the last few people huddling together on several mountain peaks, the only dry land left on Earth. He dropped them a few cracked nut shells, which served as vessels for the survivors, who floated away under a rainbow that Pramzimas put in the sky, indicating the deluge was finished.

After the waters abated and the remaining humans scampered out of their improvised arks, he instructed them to leap “over the bones of the Earth” (stones) nine times. Having performed as they were commanded, nine additional couples appeared to sire the nine tribes of Lithuania. Elements of this deeply prehistoric myth are mirrored in the Genesis deluge (the rainbow) and Deucalion flood (repopulating the world from stones). These considerations affirm that the Pramzimas’ version was likewise drawn from the same Atlantean tradition.

The Prince of Atlantis

A 1929 novel by American author Lillian Elizabeth Roy, who associated the decline of Atlantis with the lowering of both moral standards and immigration barriers.

Psonchis

Cited by the Roman historian Plutarch, in his Lives, Psonchis appears in Plato’s account as an Egyptian high priest who narrated the story of Atlantis for his Greek guests. “Psonchis” may be the Greek rendition of a priest or servant of “Sakhmis,” a name for the Egyptian goddess, Sekhmet, even though Psonchis belonged to the Temple of Neith. The two represented similar conceptions, and could have been syncretic versions of the same deity. Sekhmet, a variant of Hathor, was characterized as the celestial fire, a “shooting star,” that consumed Atlantis and immediately preceded its cataclysmic inundation. If the Psonchis in Kritias was indeed attached to the worship of Sekhmet, Plato’s version of Atlantis appears all the more credible.

Punt

A distant land of great wealth and friendly natives visited by several, large-scale mercantile expeditions from dynastic Egypt. Although conventional Egyptologists have long assumed Punt was Somalia, their supposition has been proved incorrect by both the expeditions’ recorded sailing times (three years was too long a period for round-trip voyages from Egypt to East Africa) and the non-African goods imported. Moreover, Senemut, the Egyptian admiral in charge of a commercial fleet making for Punt, recorded the changing positions of the stars, as his ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope, at the bottom of Africa, on a westerly heading. After 608 b.c., Pharaoh Nekau II sponsored a circumnavigation of Africa, which similarly took three years.

“Punt” appears to have actually been a term used to define the foreign expedition itself, not any particular land visited during the course of a single, extended voyage. The “country of Punt” was actually known as “Hathor’s Land,” after the goddess of fiery destruction from the sky associated in the Medinet Habu wall texts with the sinking of Neteru, that is, Atlantis. Hathor, in fact, was hailed as “Lady of Punt.” Although the most famous voyage to Punt was ordered by

Queen Hatshepsut in 1470 b.c., it was neither the first nor last. Her expedition was outstanding, however, because she faithfully recreated Punt architecture for her temple at Deir el-Bahri, whose un-Egyptian structures were intended to memorialize her great commercial achievement. Nothing remotely resembling this complex ever appeared in East Africa, where academic opinion erroneously locates Punt.

Many of the goods listed by Egyptian bureaucrats as Punt exports, such as amber, never came from the area of Somalia. Amber is still exported from the Atlantic islands, particularly the Canaries. Moreover, the records of Ramses II report that his largest ships, known as menechou, “reached the mountain of Punt.” While Somalia has no mountain, Plato described the island of Atlantis as “very mountainous.” The Queen of Punt, during the Hatshepsut expedition, was named Ati, a possible derivation of “Atlantis.” She and her King, Parihu, were not negroid, but white-skinned, with aquiline features similar to those of the Atlantean “Sea Peoples” portrayed on the walls of Ramses Ill’s “Victory Temple.”

Ati’s people, the Puntiu, “wore long beards which, when they were plaited, looked just like the beards of the Egyptian gods” (Montet, 86). Egyptian deities were associated with the rising and setting of the sun, never in the south, the direction of East Africa. The Puntiu were themselves said to have worshiped the Egyptians’ supreme solar god, Ra, and built a great temple to Amun, the sky-god, none of which has ever had anything to do with Somalia. Hatshepsut’s well-preserved ruins are undoubtedly the last surviving specimens of public buildings as they appeared in 15th century b.c. Atlantis, which was one of Egypt’s wealthiest but farthest trading partners.

Revealingly, the last Punt expedition took place at the very beginning of Ramses Ill’s reign, circa 1200 b.c. A short time following—two to five years, possibly even a few months—Atlantis was destroyed, and some of its survivors invaded the Nile Delta. Nekau II, mentioned previously, undertook the circumnavigation of Africa six centuries later, specifically to determine if anything was left of the Atlantean Punt, but his hired Phoenician sailors returned empty-handed. Nekau reigned at a time when his XXVI Dynasty was actively engaged in promoting a renaissance of Egyptian culture and history, when old documents describing rich expeditions to Punt were reevaluated. His capital was Sais, the same city where the story of Atlantis was preserved in the Temple of Neith. All these elements were certainly related, and strongly imply an Atlantean identity for Punt.

Pauwvota

A flying vehicle, as described in Hopi accounts of their pre-flood ancestors. (See Vimana)

Pu Chou Shan

Literally, the “Imperfect Mountain,” among the oldest recorded Chinese myths almost certainly dating from the Shang Period, circa 1200 b.c. It tells that after the primeval goddess, Nu Kua Shih, created humanity, she worked with men and women to build the first kingdom, and a golden age of greatness spread around the Earth. Many years later, one of her divine princes, out of envy, fought to overthrow her. During the heavenly struggle that ensued, his fiery head struck Pu Chou Shan. It collapsed into the sea, resulting in a global flood that obliterated civilization and most of mankind.

The story of Nu Kua Shih is a poetic recollection of the comet impact associated with the deluge of Lemuria, some 3,500 years ago.

Puna-Mu

Literally the “Stone from Mu,” or “green stone,” terms for jade, highly prized by New Zealand Maoris for its association with the sea that overwhelmed their ancestral homeland.

Pur-Un-Runa

The “Era of Savages” recounted in the Inca story of Manco Capac marked a time of decadence at the “Isle of the Sun.” The Pur-Un-Runa immediately preceded the obliteration of this splendid island-kingdom in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean by fire and flood. Manco Capac, his wife and entourage survived by sailing to South America. His Andean version parallels exactly Plato’s description of the degeneracy that befell the inhabitants of Atlantis prior to their capital’s destruction.