Leucaria

A Latin version of the ancestress cited in Plato’s account of Atlantis, she and her husband founded the city of Rome. (See Italus, Kritias, Leukippe)

Leukippe

“The White Mare,” the first woman of Atlantis mentioned briefly by Plato in Kritias. A white mare motif in association with Atlantean themes appears in various parts of the world. The most prominent example appears at England’s Vale of the White Horse, north of the Berkshire chalk downs, in Uffington. The 374-foot long hill-figure depicts a stylized horse cut into the turf. It is traditionally “scoured” by local people, as they tramp around the outline of the intaglio seven times every Whitsunday to preserve the image. Whitsunday, or “Pentecost,” is a festival celebrated every seventh Sunday after Easter. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Ghost on Christ’s disciples after his crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension to heaven, and marks the beginning of the Church’s mission throughout the world. “Whitsunday” supposedly derives from special white gowns worn by the newly baptized. But all this may be a Christian gloss over an original significance that was deliberately syncretized by Church officials anxious to dilute and absorb “pagan” practices.

While the seven annual scourings of the White Horse parallel the seven Sundays following Easter and ending with “White Sunday,” 7 was, many centuries before, regarded as the numeral of the completion of cycles by the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, and his followers, including Plato, throughout the Classical World. Moreover, the British hill-figure is deeply pre-Christian, even pre-Celtic, dating to 1200 b.c. This is also the most important time horizon in Atlantean studies, because it brackets the final destruction in 1198 b.c. Some survivors from the catastrophe may have immigrated to England, where they created the White Horse intaglio to commemorate the first lady of their lost homeland while celebrating their renewed life in Britain. These were possibly the original sentiments taken over by the analogous death and resurrection of Christ at Pentecost. Even the very term, “Whitsunday,” may not have been occasioned by Christian baptismal garb, but more likely arose from the White Horse itself. Pentecost is only known in Britain as “Whitsunday” (that is, “White Sunday”).

The cult of the white horse persisted throughout Celtic times, Roman occupation, and centuries after in the British worship of Epona, from which our word “pony” derives. White horse ceremonies rooted in prehistory are still performed at some seaside villages in the British Isles, and are always associated with sailing. A particularly Atlantean example is Samhain, (pronounced sovan or sowan), or “end of summer” celebration, a survivor from deep antiquity. In parts of Ireland’s County Cork, the Samhain procession features a man wearing the facsimile of a horse’s head and a white robe. In this costume he is referred to as the “White Mare,” and leads his celebrants down to the seaside. There he wades out into the water, pours a sacrificial libation, then recites a prayerful request for a good fishing harvest. This ritual occurs each November 1, the anniversary of the destruction of Atlantis.

The Greeks commonly envisioned foaming waves as “whites horses,” so Leukippe was appropriately named. The Earth Mother Goddess Demeter was sometimes referred to as Leukippe, the White Mare of Life. As Demeter was part of the Atlantean mystery cult, The Navel of the World, Leukippe may have been its original and central figure. In a North American plains’ version of the Great Flood, ancestors of the Lakota Sioux were saved by a sea-god who rises up from the waves riding a great white horse.

Lifthraser and Lif

In Norse myth, the husband and wife who survived a world-ending flood to repopulate the world. Every Scandinavian is a descendant of Lifthraser and Lif.

Limu-kala

Hawaiian for the common seaweed (Sargassum echinocarpum), distinguished by its toothed leaves, used as a magical cure. A lei of limu-kala was placed around the neck of the patient, who then walked into the sea until the waves carried the garland away and, with it, all illness. It was also eaten by mourners as part of funeral rites. Limu-kala leis still adorn fishing shrines and ancient temples, or heiau, throughout the Hawaiian Islands. Its name and functions clearly define limu-kala’s Lemurian origins.

Ling-lawn

The supreme sky-god worshiped by the Shans, a tribal people inhabiting northeastern Burma (Myanmar). Offended by the immorality of his human creations, Ling-lawn dispatched the gods to destroy the world. His myth relates, “They sent forth a great conflagration, scattering their fire everywhere. It swept over the Earth, and smoke ascended in clouds to heaven.” With all but a few men and women still alive, his wrath was appeased, and Ling-lawn extinguished the burning world in a universal flood that killed off all living things, save a husband and wife provisioned with a bag of seeds and riding out the deluge in a boat. From these survivors, life gradually returned.

The fundamental similarities of Ling-lawn’s flood story with accounts in other, distant cultures is particularly remarkable in view of the obscure Shans’ remote isolation. Doubtless, their ancestors experienced the same natural catastrophe witnessed by the rest of humanity.

Llyn Syfaddon

Also remembered in some parts of Wales as Llyn Savathan, Llyn Syfaddon was the great kingdom of Helig Voel ap Glannog, which extended far out into the Atlantic Ocean from Priestholm, until it sank entirely beneath the sea. Another name for the drowned realm, Llys Elisap Clynog, seems related to Elasippos, the Atlantean king in Plato’s dialogue, Kritias.

Llyon Llion

Remembered as the “Lake of Waves,” which overflowed its banks to inundate the entire Earth. Before this former kingdom was drowned, the great shipwright Nefyed Nav Nevion completed a vessel just in time to ride out the cataclysm. He was joined in it by twin brothers, Dwyvan and Dwyvach who, landing safely on the coast of Wales, became the first Welsh kings. This myth is less the slight degeneration of an obviously earlier tradition than it is an example of the Celtic inclination toward whimsical exaggeration, making a mere lake responsible for a global flood. In all other respects, it conforms to Atlantean deluge accounts throughout the world, wherein surviving twins become the founding fathers of a new civilization.

Llys Helig

A stony patch on the floor of Conway Bay, sometimes visible from the shore during moments of water clarity, and regarded in folk tradition as the site of a kingdom formerly ruled by Helig ap Glannawg. He perished with Llys Helig when it abruptly sank to the bottom of the sea. The stones taken for the ruins of his drowned palace are part of a suggestive natural formation that recalls one of several Welsh versions of the Atlantis disaster. Others similarly describe Llyn Llynclys and Cantref-y-Gwaelod. A large, dark pool of fathomless water in the town of Radnorshire is supposed to have swallowed an ancient castle known as Lyngwyn. So many surviving mythic traditions of sunken kingdoms suggest that the Atlanteans made an enduring impact on Wales.

Llyn Savathan

Known in other parts of Wales as Llyn Syfaddon, it was the extensive kingdom of Helig Voel ap Glannog, whose great possessions, extending far into the sea from Priestholm, had been suddenly overwhelmed by the sea. His name is remarkable, because it contains the “og” derivative of Atlantean deluge heroes in other parts of the world. Another Welsh flood tradition, Llys Elisap Clynog, repeats the “og” theme.

Lono

The white-skinned man-god who arrived long ago by ship in the Hawaiian Islands, bringing the first “uala, or sweet potato to the natives. His name is still invoked at every stage in its planting, tending, and harvesting. Lono instituted and presided over the makahiki celebrations, which began every late October or early November, the same period used for ceremonies commemorating the dead in various parts of the world, such as Japan’s Bon, Thailand’s Lak Krathong, Christian Europe’s and pre-Columbian Mexico’s All Souls’ Day, and so on. This is the time of year associated with the final destruction of Atlantis.

Like these foreign celebrations, the dating of the makahiki, a new year’s ceremony, was determined by the first appearance of the Pleiades, or “Atlantises,” above the horizon at dusk, because it was at this time that Lono traditionally arrived from Kahiki, one of several names by which the sunken kingdom was known throughout the Pacific. Ironically, the famous British explorer, Captain James Cook, landed at the same anchorage, Kealkekua, in Hawaii’s Kona District, where Lono first appeared. Cook was not the only white man to have followed so closely in the footsteps of a prehistoric predecessor. Both Cortez in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru were identically mistaken by the indigenous people for Quetzalcoatl, the “Feathered Serpent,” and Viracocha, “Sea Foam,” earlier white-skinned visitors. Clearly, these vastly separated traditions establish a form of prehistorical meeting common to them all.

Carried throughout the makahiki was a ritual image of Lono consisting of a tall upright wooden pole, at the top of which was a crosspiece from which were hung sheets of white bark cloth and lei of fern and feathers. The carved figure of a bird surmounted “Father Lono,” or this Lonomakua. Its resemblance to the chief symbol for Mu, as described by James Churchward, is remarkable. Lono’s identification with this sunken kingdom is underscored by his title, Hu-Mu-hu-Mu-nuku-nuku-apua’a, which indicates he could “swim” from Mu between the islands like a fish, a reference to his skill as a transoceanic mariner. His myth is the folk memory of an important culture-bearer from the lost civilization of the Pacific.

The Lost Garden

Published in 1930, G.C. Foster’s witty spoof of all “lost continent” theories has reincarnated Atlanteans hotly debating the real or imagined existence of Lemuria, employing all the standard arguments used to either support or discredit a historical Atlantis.

Luondona-Wietrili

The original homeland of the Timor people, who universally claim descent from this sunken kingdom. According to them, the little islet of Luang is the only dry land surviving from the much larger island. Luandona-Wietrili was destroyed by natural catastrophes in the form of a monstrous sailfish for the divisiveness of its leaders.

Lycaea

A Greek ceremony conducted at Mount Lycaeus commemorating the destruction of a former human epoch by a worldwide catastrophe. Each Lycaea reenacted the story of an antediluvian monarch, Lycaon, who tried to deceive the king of the gods into committing cannibalism. Seeing through the trick, Zeus punished both Lycaon and his degenerate people with a genocidal flood.

Of the three distinct deluge myths known to the Greeks, the Lycaea seems closest to Plato’s account of Atlantis, which likewise grows degenerate and is annihilated by Zeus with a watery cataclysm. The deeply pre-Platonic roots of this rendition tend to thus confirm at least the fundamental veracity of both Timaeus and Kritias and the Lycaea itself. The previous Deucalion and Ogygean floods belonged to geologic upheavals and mass migrations of Atlantis in the late fourth and third millennia b.c.

Lyonesse

In British myth, the “City of Lions” was the capital of a powerful kingdom that long ago dominated the ocean. Like Plato’s description of Atlantis, Lyonesse was a high-walled city built on a hill which sank beneath the sea in a single night. Only a man riding a white horse escaped to the coast at Cornwall. Two families still claim descent from this lone survivor. The Trevelyan coat-of-arms depicts a white horse emerging from the waves, just as the Vyvyan version shows a white horse saddled and ready for her master’s flight. While both families may in fact be direct descendants of an Atlantean catastrophe, Lyonesse’s white horse connects Leukippe, “White Mare,” mentioned in Plato’s account as an early inhabitant of Atlantis, with the White Horse of Uffington, a Bronze Age hill-figure found near Oxford. Tennyson believed Camelot was synonymous for “the Lost Land of Lyonesse.” Indeed, the concentric configuration of Atlantis suggests the round-table of Camelot.

In another version of the Cornish story, Lyonesse’s royal refugees sailed away to reestablish themselves in the Sacred Kingdom of Logres. While the medieval Saxon Chronicle impossibly dates the sinking of Lyonesse to the late 11th century a.d., its anonymous author nonetheless records that the event occurred on November 11, a period generally associated with the destruction of Atlantis. Traditionally, the vanished kingdom is supposed to have sunk between the Isles of Scilly and the Cornish mainland, about 28 miles of open sea. A dangerous reef, known as the Seven Stones, traditionally marks the exact position of the capital. These suggestive formations appear to have helped transfer the story of Atlantis, recounted by survivors in Britain, to Cornwall.

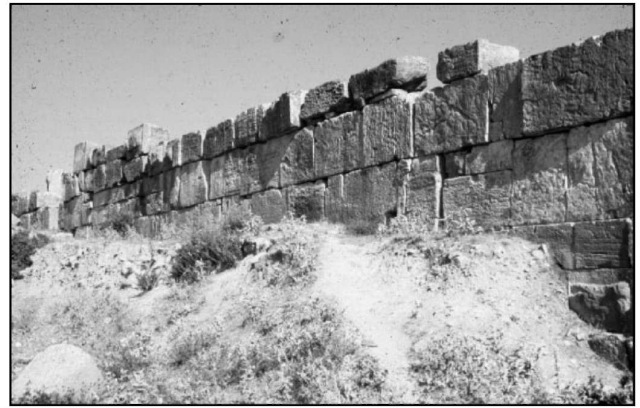

The ruins of Lixus, coastal Morocco, associated with Atlantean king, Autochthones.